Abstract

New technologies and ubiquitous systems present new forms and modalities of interaction. Evaluating such systems, particularly in the novel socioenactive scenario, poses a difficult issue, as existing instruments do not capture all aspects intrinsic to such scenario. One of the key aspects is the wide range of characteristics and needs of both users and technology involved. In this paper, we are concerned with aspects of both Universal Design (UD) and Natural User Interfaces (NUIs). We present a case study where we applied, within a socioenactive scenario, evaluation instruments relying on principles and heuristics from these areas. The scenario involved six children from a hospital that treats craniofacial deformities, playing in a rich interactive environment with displays and plush animals that respond to hugs. Our results based on the analysis of the evaluation conducted in the case study suggest informed recommendations of how to use the evaluation instruments in the context of socioenactive systems and their limitations.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Accessibility

- Interaction evaluation

- Ubiquitous computing

- Pervasive

- Natural User Interfaces

- Universal Design

- Universal Access

1 Introduction

The emergence of novel technological devices prompts new forms of interaction involving the body and the environment. This scenario allows people to better express themselves and further exchange information. As ubiquitous and pervasive computing becomes a reality in our daily lives, universal access to new technological scenarios and underlying information becomes a necessity and deserves attention [4].

As important as the development of new interactive technologies (e.g., computational devices, their integration and communication in physical contexts), the evaluation of these technologies in diversified scenarios of use by involving users with different characteristics plays a key role for systems acceptance and adequate use. Although there are various classic evaluation instruments and tools for Usability [10], Accessibility [3] and Universal Design [16], they have not been elaborated to address relevant accessibility aspects of this new technological context, which involve ubiquitous and pervasive computing. For example, the heterogeneity of systems and their behaviors, along with the inherent difference between the human side of the interaction, creates an ecosystem where no formal specifications can fully address all accessibility and usability aspects.

Enactive systems, as proposed by Kaipainen et al. [6], aim to draw away from goal-oriented and conscious interactions, going towards an interfacing that is “driven by bodily involvement and spatial presence of the human agent without the assumption of conscious control of the system”. It is possible to go even further and add a social component to this concept, in a way that collective actions as well as interaction among people affect and are affected in a coupled way by the computer-based system. This concept is the core of what we name “Socioenactive Systems” [2]. These systems require new artifacts and tools, to allow us to evaluate whether such systems provide universal access to information.

In this paper, we investigate evaluation issues regarding the Universal Access provided by socioenactive systems. In particular, we present and discuss the results of applying two evaluation tools within a socioenactive system scenario. The research involved a workshop conducted in the context of a hospital for face deformities correction. Six children, parents and hospital staff participated in the workshop. The system explored in the workshop consisted of plush animals with embedded sensors that measure the intensity of hugs, a display and an interactive Christmas tree. As the children hug the animals, the system offers various feedbacks.

For evaluation purpose, we chose the 7 Universal Design Principles [16], and the 13 Heuristics for Natural User Interfaces (NUIs) [8]. The former was selected because of its relevance and simplicity to look at Universal Design; the latter was chosen because NUIs, or natural interaction, are part of the ubiquitous, pervasive and embodied context of (socio)enactive systems. Our investigation aimed to answer to which extent these instruments are able to analyze key aspects necessary for duly evaluating Universal Access in socioenactive systems.

This investigation provides 2 major contributions. We discuss the instruments limitations and the possibilities of combining and extending them; (1) we provide results and limitations of an exploratory literature review concerning evaluation methods and tools for Accessibility and Universal Design, which are relevant for the context of socioenactive systems. (2) Based on the resulting analysis of the instruments application in the workshop, we provide guidelines on which instruments to apply in the aforementioned technological scenario and recommendations for carrying out the evaluation.

This paper is organized with the following structure: Sect. 2 presents background on NUI Heuristics and Universal Design Principles. Section 3 discusses the findings of our exploratory literature review. Section 4 details the case study, including its context, methodology, results and the lessons learned discussing the findings. Whereas Sect. 5 presents the proposed recommendations on how to use the heuristics and principles as an evaluation instrument, Sect. 6 presents our concluding remarks and points out future research.

2 Theoretical Background

This section describes the theoretical background on (socio)enactive systems (Subsect. 2.1), the 7 Principles of Universal Design (Subsect. 2.2), and the set of 13 NUI Heuristics (Subsect. 2.3).

2.1 (Socio)enactive Systems

The core concept of enaction comes from what Varela et al. [18] call the “enactive approach”, a two-part circular definition: “In a nutshell, the enactive approach consists of two points: (1) perception consists in perceptually guided action; and (2) cognitive structures emerge from the recurrent sensorimotor patterns that enable action to be perceptually guided”. Whereas the first point gives a definition for perception, the second point explains how such perception at the same time builds and is built by the interactions with the world. Kaipainen et al. [6] proposed a way to bring this concept into the realm of computer systems, with the concept of “enactive systems”. The main idea is to provide a dynamic coupling between the human and the technological parts of the interaction, in a way that there is not necessarily a conscious control of the system, but rather a bodily involvement of the human agent. In this sense, the perceptually guided action consists of feedbacks the system might provide for human actions, and vice-versa; i.e., the human’s behavior is affected by the system’s responses, and at the same time, the system changes its behavior according to the person’s (re)actions.

The concept of socioenactive systems [2] adds the social component into the mix, in a way that considers not only the human-technology interactions, but interactions among humans and between different technologies. This creates a complex ecosystem of interactions, where it is purposely difficult to draw the lines separating each agent. Although these ideas are close to the concept of ubiquitous computing proposed by Weiser [19], socioenactive systems represent a novel concept, still under construction. Therefore, there is still no theoretical and methodological basis for their design and evaluation. In particular, a great challenge lies in understanding the needs and characteristics of the environments, technologies and people that are part of the socioenactive systems. Thus, new tools, techniques and processes need to be created. This includes evaluation instruments to assess systems’ quality criteria.

2.2 Universal Design (UD) Principles

Universal Design (UD), defined by Story et al. [17] consists in the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design. It is aligned with the concept of developing accessible interfaces without the discrimination of users. Story [16] has established seven UD Principles, which can serve the following purposes: to guide the design process, to evaluate existing designs, or to teach designers and consumers about the characteristics of more usable products and environments. Each of the seven principles has four or five guidelines describing key elements that should be present in an UD. Table 1 summarizes the short descriptions of each principle.

2.3 Natural User Interface (NUI) Heuristics

Natural User Interfaces (NUIs) refer to an interface paradigm that aims to provide interactions that feel natural to the user, such as gestural, and touch-based interfaces [20]. Norman [11], however, has claimed that, despite harboring great potential, NUIs – and gestures, in particular – are not natural, given they can be hard to learn or to remember. Furthermore, they are also subject to cultural differences, given that a gesture that is friendly in a culture might be offensive in another. This is also true if we think in terms of Accessibility, i.e., how inclusive gestures (or other types of NUIs) can be to people in special conditions, such as those with motor or visual disabilities. Therefore, although NUIs represent a promising paradigm, it is not simple to achieve their promised “naturalness”.

Considering these challenges, Maike et al. [8] proposed 13 heuristics for the design and evaluation of NUIs in the context of accessibility. These heuristics have been applied and tested in distinct scenarios in which visually impaired users were able to detect and recognize people in the surroundings through Assistive Technology (AT) devices made with NUIs, such as the Microsoft Kinect and a wristband smartwatch. Table 2 presents a summary of the 13 NUI Heuristics.

In this work, we explore these heuristics in an original fashion. Our goal is to understand their potential as part of an evaluation technique for socioenactive systems.

3 Related Work

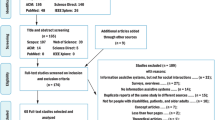

To better understand the subject, we conducted an exploratory literature review looking for papers in the following conferences: HCII (International Conference on Human Computer Interaction), UAHCI (International Conference on Universal Access in Human Computer Interaction), and in the journal UAIS (Universal Access in the Information Society). Two separate searches were conducted. In the first, we searched for papers with all three keywords: “enactive systems”, accessibility and usability. Because this search returned a low number of related papers, we did a second search, with the following keywords: “universal design” and evaluation.

This exploratory search found that the overall existing literature emphasizes Web accessibility dealing with specific disabilities instead of a design for all perspective. For instance, Orozco et al. [13] proposed a methodology for heuristic evaluation of Web accessibility, based on the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 [5], as defined by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). The evaluation process focused on features and specific barriers that people with disabilities needed to overcome to access information on websites, lacking an analysis from a Universal Design standpoint.

On a similar fashion, Mi et al. [9] proposed a heuristic checklist for accessible smartphone interface design. It was developed based on a case study evaluating high-fidelity smartphone prototypes produced by a commercial manufacturer. A comparison was performed between gestures used by people with normal vision condition and those with visual impairments. The authors provided a survey containing the specification and its classification into six general categories as a way to identify the users’ requirements. The obtained results provided support for an accessibility checklist, although still limited to design support in the early stages of portable design projects. They relate some Universal Design Principles, by highlighting user’s preferences for some of the requirements.

From a device and software standpoint, we found investigations about iTV [12], mobile audio games [1] and a smartphone-based system [14]. Oliveira et al. [12] conceptualized, prototyped and validated an iTV service designed for visually impaired people, which integrates new functionalities based on the Universal Design philosophy. The authors performed a prototype test and evaluation by means of direct observation and semi-structured interview with a group of visually impaired users.

Rahman et al. [14] proposed a smartphone application called EmoAssist, which provides access to non-verbal communication for people who have visual impairments. The system analyses person’s face to predict their behavioral expressions (e.g., yawn) and the affective dimension (valence, arousal or dominance). Based on these predictions the system provides adequate auditory feedback to the user. The authors applied an usability study, as an evaluation tool, and conducted subjective studies to understand users’ satisfaction.

Araújo et al. [1] searched for accessibility guidelines for digital games, then compiled and classified the found ones. The authors focused on specialized games’ features for blind people. The authors identified ten recommendations considered to be minimal requirements for the design and development of mobile audiogames. Finally, based on these recommendations, the authors proposed a questionnaire with 32 questions considering the WCAG [5]. These recommendations aid developers in testing their mobile audio games. Although authors mention Universal Design a few times, their work emphasized exclusively visually impaired users.

Aiming to apply UD in the design process, Liu et al. [7] developed specific project criteria, which is based on the seven Universal Design (UD) Principles. To illustrate the scenario, the authors used a voting system, called EZ Ballot, which was designed following Universal Design principles. It has multimodal input and output that eases the voting process and allows electors to simply answer yes/no questions that are presented in different ways. Therefore, people can use the system regardless of their abilities.

Our related work analysis indicates that existing studies focus on specific devices or audiences without considering a systemic view of a scenario. Thus, this review points out a gap in literature, in which the accessibility evaluation is conducted without considering broader contexts or audiences. Our goal, then, is to propose an evaluation method, tool and guidelines suited to promote Universal Design as well as to consider specific characteristics of socioenactive systems, once in these systems human and computational processes interact dynamically and fluidly, providing feedback. They use new technologies, novel interaction modalities and ubiquitous computing, which demand the consideration of new factors such as emotional, physical and cultural that influence the design and evaluation of these systems.

4 Case Study

In this work, we conducted a case study in the context of a socioenactive system, applying evaluation tools to capture: (1) the unique aspects of such context; and (2) Accessibility and Universal Design issues. In the following subsections, we present further details. Subsection 4.1 explains the context in which the case study was developed and the participants. Subsection 4.2 presents the methodology used in conducting the study. The results are presented in Subsect. 4.3, where Subsect. 4.3.1 indicates the Universal Design Principles observed, and Subsect. 4.3.2 contains the details on the analysis of NUI Heuristics. Finally, Subsect. 4.4 discusses the lessons learned.

4.1 Context and Participants

This work is part of a five-year research project named “Socioenactive systems: investigating new dimensions in the design of the interaction mediated by ICT (Information and Communication Technologies)”Footnote 1 [2]. Its main objective is to formulate the concept of “socioenaction”, and build a conceptual framework that supports the design and development of socioenactive systems, taking into account the participants’ differences, i.e., their needs, cultural context, abilities and values.

Our case considered the context of a hospital named Brazilian Society for Research and Assistance for Craniofacial Rehabilitation (SOBRAPAR)Footnote 2. Located inside the campus of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), this private philanthropic institution offers rehabilitation treatments for people with craniofacial deformities. Their multidisciplinary team is constituted by plastic surgeons, speech therapists, otolaryngologists, psychologists, social workers, orthodontists, neurosurgeons, physiotherapists, nurses, and more. The institution revenue is from donations, government funds and a permanent bazaar where they sell every sort of donated items.

We have established a partnership with SOBRAPAR to conduct experimental research, with the approval of UNICAMP’s ethics committee. We invited a small group of children and their parents to participate on “workshops” approximately once a month, usually while they are already on the hospital waiting for treatment. The workshops involved affection aspects, and making the treatment process in the hospital less stressful for the children. In order to do so, the activities were centered around interactive plush animals [15]. Two of these animals, a bear (named Teddy) and a monkey (named Chico), have pressure sensors inside them to detect hugs and their intensity. They also have sound speakers, so they can provide feedback like compliments on the hugs, or asking for more hugs. The intensity of the hugs is represented graphically on a TV screen, by means of a speedometer-like gauge we call “hug-o-meter”. From time to time, the TV displays photos of the workshop, taken in real time by another plush animal: an owl with a camera inside it. Figure 1 shows the arrangement of the children in the workshop and the artifacts used.

The workshop reported in this paper happened on December 10th 2018. Six children aged between 7 and 11 years participated in this workshop. At least one of their parents or legal responsible were present, along with a speech therapist from the hospital staff. Before participating, they were all made aware that the activity was part of a research project, and that they had to sign consent forms, but were free to give up at any time. For this specific workshop, we brought an interactive Christmas tree. The idea was to let the children figure out how to light up the tree by hugging the two plush animals, Teddy and Chico. The tree had six horizontal layers of lights, and reaching high levels on the hug-o-meter, made one level of lights blink; repeating that after a certain amount of times made the level stay lit. Our proposal was to make the six levels stay lit, from the bottom to the star on the top. The children did not receive these instructions; they were asked to figure it all out by themselves.

The children were placed in a circle on a carpet on the floor, allowing for more interaction between them, so that they could observe all the action around them. The TV screen that provided the visual effects and the tree were positioned near the circle, at everyone’s sight. The owl was placed at a little distance so it could capture good images of the interaction. The stuffed animals were passed around the circle by all children, and as they hugged, the hug-o-meter level was changed.

4.2 Methodology

During the workshop, we had four Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) researchers acting as observers. They focused on the actions, environment and feedback of the proposed solutions. For the evaluation, the seven Principles of Universal Design and the 13 NUI Heuristics were used. The first was selected because of its relevance and simplicity to look at Universal Design; the latter was chosen because NUIs are part of the ubiquitous, diffused and embodied context of (socio)enactive systems.

The research aimed to investigate to which extent these instruments are able to capture the subtleties for the assessment of universal access in socioenactive systems. Both instruments were used as forms to be filled. For each UD principle or NUI Heuristic, there was room for free-text observations, and a compliance scale of −4 (completely not compliant) to 4 (totally compliant), where 0 means “not applicable”. Two observers analyzed whether the socioenactive system complied with each UD principle or not, and the other two observers analyzed whether it complied with each NUI heuristic or not.

After the workshop, a debriefing session between the researchers was held for clarification and discussion on the results of the observations. In addition to the initial researchers, 3 others HCI specialists were present. As this session intended to analyze the obtained results in a conceptual way, the participants (children) in the workshop did not attend. The session was conducted in three stages. First, each of the scores attributed to each of the UD Principles were written on a whiteboard for the visibility of all researchers, and a brief discussion was established regarding the observations made by the researchers who took the role of observers during the workshop. The same process was repeated for the NUI Heuristics. Afterwards, we made a general discussion about the results from the UD Principles and the NUI Heuristics, as well as and their application in socioenactive systems scenarios.

4.3 Results

The analysis of the scenario was performed taking into account the NUI Heuristics and the UD Principles. In addition to the scores assigned on the compliance scale, each of the researchers wrote down justifications for their scores. In the following, we present the result analysis concerning the principles, heuristics and the compliance scores.

4.3.1 Assessment of Universal Design Principles

In relation to the seven UD principles, Table 3 shows the scores on the compliance scale and a summary of the justifications given by the observers.

4.3.2 Assessment of NUI Heuristics

Table 4 presents the scores on the compliance scale assigned to each of the NUI Heuristics, and a synthesis of the justifications given by the observers.

4.4 Lessons Learned

The results from the previous subsection were thoroughly discussed in the debriefing session. While discussing the first UD principle “Equitable Use”, a question arose regarding how the system would work for a person with no arms. A possible solution that came up was somehow making the plush animal hug the person, instead of the other way around. Another solution would be for the person to press their face against the animal, instead of using the arms. The same question came up in the discussion of the second principle, “Flexibility in Use”. In this case, another interesting point was raised, about the (socio)enactive aspect of the system; it was suggested that the threshold of the intensity of the hug to trigger an effect on the tree could vary according to the group. For instance, a group of younger children could have weaker hugs than a group of older children; the system would adapt its threshold accordingly for each group, maintaining consistency. These two questions show how important the debriefing process is, as it brings up features and solutions that are not necessarily considered during the observation of the activity, when there is little time for deeper reflections.

In turn, for the NUI Heuristics, during the debriefing session we noticed that the observations focused on the relationship between the artifacts of the system (i.e., Teddy, Chico, the owl, the TV…). Therefore, while the UD Principles focused more on the microscopic evaluation, looking at individual parts of the interaction, the NUI Heuristics provide a macroscopic view of the system, regarding aspects that are an essential part of the (socio)enactive proposal, such as social, collaboration and engagement. Such aspects were not elicited by the UD Principles, which means that for evaluating socioenactive systems, additional instruments are needed.

Also during the debriefing session, the researchers who observed the UD Principles reported having difficulty in interpreting the principles. This is probably due to the form created as the evaluative instrument; each principle had not only its brief description, but also a set of guidelines that further detailed what had to be observed. However, the compliance scale was relative to the entire principle, so sometimes one single item would drop the score for the entire principle. This suggests that a more refined score strategy is necessary to deal with these aspects.

5 Heuristics and Principles as an Evaluation Instrument

Comparing the results from the two instruments, we mapped the UD Principles into the NUI Heuristics (cf. Table 5). As this table shows, most heuristics have two principles related to them, while some heuristics have one principle. The latter cases could indicate a feature that is not entirely present in the UD Principles. We can also observe that there are heuristics which do not have principles associated with them, which reinforces our hypothesis that the principles were not enough to evaluate the context of socioenactive systems. However, we highlight that the NUI Heuristics are complemented by the principles, with a more specific focus on UD (Table 6).

The results from using the NUI Heuristics and the UD Principles as evaluation instruments allowed us to propose recommendations on how to use them, particularly in the context of socioenactive systems or similar (e.g., pervasive or ubiquitous). In Table 5, we find which principles share similarities with which heuristics. Based on this information, we propose a checklist to be used by observers while performing an evaluation (cf. Table 6). The format of a checklist seems appropriate, especially because it mitigates the issue of one item dropping the score of an entire principle. In addition, the checklist makes it simpler to merge the two instruments together.

As a result, we present our proposed checklist, which contains a total of 40 items. We suggest using this as a form, where each item has a scale of conformity where a value of correspondence to what is being observed can be marked. Also, for each there will be a box to write notes about it. We disencourage the use of a binary scale (e.g., “compliant” and “non-compliant”, or “check” and “unchecked”), since the compliance scale with a wider range stimulates reflexion and discussion, as we have learned from our case study. We point out that four guidelines from the UD Principles were not included in our checklist, two from Principle 4, and two from Principle 5. Mostly, we found that they were redundant with other guidelines from their same principle, so we chose not including them to make the checklist more concise.

6 Conclusion

In the current ubiquitous and pervasive scenario, the emergence of new technological devices brings new forms of interaction. In fact, as we move towards Weiser’s [19] vision of an invisible technology, the idea of a “dynamic mind-technology embodiment” [6] from enactive systems becomes increasingly plausible and relevant. Furthermore, the novel concept of socioenactive systems demands new tools and techniques for the design and evaluation of such systems. In particular, there is a need to consider diversified scenarios, environments, and different user characteristics.

Considering such challenging scenario, this paper investigated how much two existing evaluation instruments are applicable to evaluate universal access in socioenative systems. We presented the results of applying existing instruments to evaluate a socioenactive system, seeking to consider the issues that are not typically present in other types of systems.

The results of our case study indicated the principles alone were not able to provide insights into key aspects of socioenactive systems, such as engagement, wayfinding and social factors, like acceptance or awareness of others. However, we found that the principles contribute with a microscopic view, particularly regarding Universal Design, that the heuristics do not have. Therefore, the two complement each other well, which allowed us to merge the two and propose a checklist for the design and evaluation of systems in socioenactive scenarios, or those similar to them. Such results allowed us to propose a new instrument, which intends to supply the demand for design and evaluation tools for socioenactive systems.

Our findings pointed out to recommendations of use for evaluation instruments, such as the proposed checklist. For instance, a debriefing session after the initial collection is great for evaluators to reflect upon their observations, because there is not enough time for that during the data gathering. This way, the discussion among researchers (in this case, in the role of evaluators) is great for raising questions and proposing solutions to problems found either during the observation period, or in the debriefing. We also encourage that the checklist has room for writing notes, and a compliance scale for each item, as these two can feed the later discussion.

Future work involves testing the new instrument with socioenactive systems, possibly along with other existing guidelines, like WCAG. Introducing new tools would allow us to further improve our instrument, and contribute to a framework for designing and evaluating socioenactive systems.

Notes

- 1.

Project funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) [grant #2015/16528-0].

- 2.

Project approved by the Unicamp Research Ethics Committee [CAAE 72413817.3.0000.5404].

- 3.

The opinions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agencies.

References

Araújo, M.C.C. et al.: Mobile Audio Games Accessibility Evaluation for Users Who Are Blind. In: Antona, Margherita, Stephanidis, Constantine (eds.) UAHCI 2017. LNCS, vol. 10278, pp. 242–259. Springer, Cham (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58703-5_18

Baranauskas, M.: Sistemas sócio-enativos: investigando novas dimensões no design da interação mediada por tecnologias de informação e comunicação. FAPESP Thematic Project (2015/165280) (2015)

Consortium, W.W.W., et al.: Web content accessibility guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 (2008)

Emiliani, P.L., Stephanidis, C.: Universal access to ambient intelligence environments: opportunities and challenges for people with disabilities. IBM Syst. J. 44(3), 605–619 (2005)

Cooper, M., Reid, L.G.: Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0, pp. 1–24 (2013)

Kaipainen, M., et al.: Enactive systems and enactive media: embodied human-machine coupling beyond interfaces. Leonardo 44(5), 433–438 (2011)

Liu, Y.E., Lee, S.T., Kascak, L.R., Sanford, J.A.: The Bridge Connecting Theory to Practice - A Case Study of Universal Design Process. In: Antona, M., Stephanidis, C. (eds.) UAHCI 2015. LNCS, vol. 9175, pp. 64–73. Springer, Cham (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20678-3_7

Maike, V.R.M.L., de Sousa Britto Neto, L., Goldenstein, S.K., Baranauskas, M.C.C.: Heuristics for NUI Revisited and Put into Practice. In: Kurosu, Masaaki (ed.) HCI 2015. LNCS, vol. 9170, pp. 317–328. Springer, Cham (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20916-6_30

Mi, N., Cavuoto, L.A., Benson, K., Smith-Jackson, T., Nussbaum, M.A.: A heuristic checklist for an accessible smartphone interface design. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 13(4), 351–365 (2014)

Nielsen, J.: 10 usability heuristics for user interface design. Nielsen Norman Group 1(1) (1995)

Norman, D.A.: Natural user interfaces are not natural. Interactions 17(3), 6–10 (2010)

Oliveira, R., de Abreu, J.F., Almeida, A.M.: Promoting interactive television (iTV) accessibility: an adapted service for users with visual impairments. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 16(3), 533–544 (2017)

Orozco, A., Tabares, V., Duque, N.: Methodology for Heuristic Evaluation of Web Accessibility Oriented to Types of Disabilities. In: Antona, M., Stephanidis, C. (eds.) UAHCI 2016. LNCS, vol. 9737, pp. 91–97. Springer, Cham (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40250-5_9

Rahman, A., Anam, A.I., Yeasin, M.: EmoAssist: emotion enabled assistive tool to enhance dyadic conversation for the blind. Multimed. Tools Appl. 76(6), 7699–7730 (2017)

Silva, J.V., et al.: Explorando afeto e sócio-enação em um cenário hospitalar (02 2019) (to be published)

Story, M.F.: Maximizing usability: the principles of universal design. Assist. Technol. 10(1), 4–12 (1998)

Story, M.F., Mueller, J.L., Mace, R.L.: The universal design file: designing for people of all ages and abilities. Center for Universal Design, North Carolina State University, Raleigh (1998)

Varela, F.J., Thompson, E., Rosch, E.: The embodied mind: cognitive science and human experience. MIT Press, Cambridge (1991)

Weiser, M.: The computer for the 21st century. Sci. Am. 265(3), 94–105 (1991)

Wigdor, D., Wixon, D.: Brave NUI World: Designing Natural User Interfaces for Touch and Gesture. Elsevier, Amsterdam (2011)

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP)Footnote 3 (grant #2015/16528-0), by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) (grants #01-P-04554/2013 and #173989/2017). We also thank the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (grants #160911/2015-0 and #306272/2017-2) and the Pro Rectory of Research at the UNICAMP (grant #2018/2132).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

dos Santos, A.C. et al. (2019). Inquiring Evaluation Aspects of Universal Design and Natural Interaction in Socioenactive Scenarios. In: Antona, M., Stephanidis, C. (eds) Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Theory, Methods and Tools. HCII 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 11572. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23560-4_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23560-4_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-23559-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-23560-4

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)