Abstract

Crowdsourcing refers to an online micro-task market to access and recruit large groups of participants. One of the most popular crowdsourcing platforms is Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk). MTurkers are as reliable as traditional workers yet they receive much less monetary compensation (Pittman and Sheehan 2016). Many MTurk workers consider themselves exploited (Busarovs 2013), yet, despite this, many continue to complete tasks on MTurk. The purpose of this study is to investigate how MTurk workers dealing with inequities in effort and compensation. We experimentally manipulate expected effort and worker payment in order to compare how effort verses wage inequity affects workers’ attitudes towards a series of tasks. We found that those paid more rated the task as more enjoyable and important than those paid less. Implications of this study are discussed.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The Internet has changed the possibilities for social science research. One of the changes is through the rise of crowdsourcing. Crowdsourcing refers to using an online micro-task market to access and recruit large groups of participants. One of the most popular crowdsourcing sites is Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk). Studies have found that MTurkers are as reliable as participants from more traditional sources (Buhrmester et al. 2011), yet they receive much less compensation for their participation than other participants (Pittman and Sheehan 2016).

It is reasonable to believe that MTurk workers experience dissatisfaction over being underpaid for their work. In fact, many MTurk workers consider themselves exploited (Busarovs 2013), yet, despite this, many continue to complete tasks (called “HITs”) on MTurk. How then are MTurkers managing this inconsistency between the effort they put into tasks and the payment they receive? We believe that this inconsistency is causing MTurk workers to experience cognitive dissonance (i.e. psychological discomfort) and they are motivated to reduce this discomfort through rationalizations about the importance and enjoyment of their work. We examine this in the current investigation.

1.1 Cognitive Dissonance Theory

The theory of cognitive dissonance states that when a person holds two relevant cognitions that are in opposition to each other, this causes dissonance (i.e. psychological discomfort) to occur (Festinger 1959). For dissonance to be reduced, without changing the behavior or attitude entirely, one must either: remove or reduce the importance of dissonant cognitions or add or increase the importance of consonant cognitions (Harmon-Jones and Mills 1999). Of the several paradigms used to investigate this theory, the paradigms most relevant to the current investigation are the induced compliance and effort justification paradigm.

Induced Compliance Paradigm.

The induced compliance paradigm states that dissonance is aroused when a person does or says something that is contrary with a prior belief or attitude. Based on the prior belief or attitude, it would follow that the individual would not engage in that behavior (Harmon-Jones and Mills 1999). Festinger and Carlsmith (1959) investigated this by testing the hypothesis that the smaller the reward for saying something that one does not believe, the greater the attitudinal change in order to maintain consistency with the behavior (i.e. the lie). In their study, they had participants complete a dull, tedious task. Afterwards, researchers told participants that the confederate for the next session was running late and asked if they would fill in. Specifically they were asked if they would tell the next participant how much they enjoyed the task for either $1 or $20 in compensation. Then, participants were asked to rate their actual enjoyment of the task. Those who were given $1 rated their enjoyment of the tasks as greater than those who were given $20. Participants who received the $1 for lying to the next participant had to justify why they had knowingly told the other person a lie (i.e. that the task was enjoyable) for so little compensation. They justified their lie through changing their cognitions about the task, that is, by increasing their actual enjoyment of the task so their attitudes would be in line with their behaviors.

Applied to the current investigation, dissonance may be aroused in situations when MTurk workers believe they are not being fairly compensated for the work they are asked to perform. In this case, the dissonant cognitions are workers belief that they should be paid fairly for their work and the reality that they are being compensated much less than traditional workers for the same amount of time and effort expended. This may motivate individuals to reduce dissonance by justifying their behavior (i.e. continuing to complete tasks), such as through increased enjoyment and perceived importance of the task.

Effort Justification Paradigm.

The effort justification paradigm states that the more effort that individuals exert to achieve an outcome, they will be motivated to justify their effort exertion, and this will result increased liking for the outcome. Aronson and Mills (1959) tested this by having women undergo a severe and mild initiation to gain membership into a group. In the “severe” initiation group, women engaged in an embarrassing activity to join the group while, in the “mild” initiation group, the activity to join the group was not very embarrassing. They found that those in the severe initiation group rated the group as more favorable than those in the mild initiation group. Those in the severe initiation justified the effort they underwent to join the group by increasing their overall liking of the group.

Applying these findings to MTurk, dissonance may be aroused in situations when MTurk workers experience above-average effort exertion on tasks, such that they have to justify their continued participation. Previous research has found that one of the most reported complaints by MTurk workers about requesters was inaccurate task descriptions, specifically, advertising tasks as requiring less time to complete than in actuality (Brawley and Pury 2016). These inaccurate descriptions may cause MTurk workers to perceive such tasks as more time and effort consuming compared to tasks in which descriptions are accurate. If individuals find tasks more effort consuming than anticipated, due to inaccurate task descriptions, they may become frustrated and this frustration may motivate them to justify their effort exertion and continued participation.

1.2 Cognitive Dissonance and MTurk Workers

To our knowledge, only one study has investigated cognitive dissonance in MTurk workers. Lui and Sundar (2018) manipulated participants’ perceptions of underpayment for completing a 20-minute study by either telling participants that the researchers had received additional funding and would be able to pay each worker more than the advertised compensation amount (i.e. $1.50 compared to $.50 in Study 1 and $3.00 compared to $.25 in Study 2). They found no differences between conditions in Study 1. In Study 2, found that those offered more than advertised rated task as less important then those who were not offered any more than the advertised amount. They found that increased perceived importance of the task was, in turn, associated with more enjoyment of the task, perceived choice, and less tension.

According to the theory of cognitive dissonance, dissonance is only aroused when a person does something that is contrary with a prior attitude such that, based that attitude, it would follow that the individual would not engage in that behavior. Therefore, dissonance-arousal occurs when individuals are invested enough in an activity to need to justify their continued participation. While Lui and Sundar found group differences in Study 2, they did not get participants invested in the task before manipulating monetary compensation, unlike previous research. Therefore, although they found that differences in monetary compensation were affecting workers task attitudes, we are hesitant to interpret these findings as evidence of cognitive dissonance-motivated attitude change.

1.3 Current Investigation

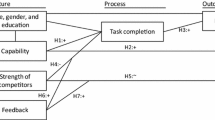

In the current investigation, we seek to replicate and extend the study by Lui and Sundar by investigating the compound effects of dissonance using both an induced compliance and effort justification framework. Although dissonance occurs in both of these situations, it remains to be tested whether the outcomes of dissonance are the same or perhaps compounded when the dissonance is aroused from two different inequalities (i.e. effort compared to payment) within the same context. In the current investigation we manipulate both perceived task effort and monetary compensation and look at how it affected workers subjective experiences of the task.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and Setting

This study employed a 2 (Effort: Anticipated vs. Unanticipated effort) x 2 (Payment: High or Low) between groups experimental design and used both quantitative and qualitative measures to gather data about the experiences of workers. The survey was distributed using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk in micro-batches over the course of six days. Participants (N = 334) were Mechanical Turk Workers from the United States. Data collection took place online, in a remote location, on an internet-accessing device (phone, desktop, or laptop, etc.).

2.2 Procedure

The study description stated that researchers were using machine learning to digitally transcribe thousands of old and damaged texts, and while the algorithms were adaptive, humans were still needed to inspect the algorithm’s accuracy. Participants were informed the purpose of this study was to use human subjects to check the algorithm’s text detection and transcription accuracy. Specifically, participants’ job was to check that the algorithms were detecting all of the letters and numbers within the texts. Participants were offered $.30 to complete the task.

During the task, participants were shown several pictures of texts and were instructed to count and record how many letters and numbers they contained. This task was purposefully very tedious to make it more effort inducing to participants. The average amount of time in the description was manipulated between participants, which served as our manipulation of perceived effort. Those in the unanticipated effort condition were told the study would only take about 5 min to complete while those in the anticipated effort condition were told the study would take about 15 min to complete. In actuality both groups completed the same study, which took about 15 min to complete.

At the end of this task, participants were told that the study was over but were given the option to complete another, ostensibly unrelated task for additional compensation. Specifically, each participant was given the following information: “Thank you for completing our study. This is a pilot study for a larger experiment we will be conducting. We would like to draw a diverse number of quality participants and we think the best way to attract quality MTurk workers is by using positive evaluations of the task provided by past participants. Therefore we are interested in getting your positive reactions to the letter counting task. You are under no obligation to complete this task, but if you do, you will be additionally compensated $.02 ($.40).” The amount of additional compensation was manipulated between participants. Those in the low payment condition will be offered $.02. Those in the high payment condition will be offered $0.40 to complete this task. Those who opted to complete the task were instructed to write a positive endorsement of the task. Those who opted to not complete the additional task were immediately directed to the final subjective experience questions that participants completed before being debriefed. Participants who completed the additional were paid $.70 for their participation, regardless of what they were offered in the description. Those who opted not to complete the additional task were paid $.30, the amount offered in the initial task description.

2.3 Dependent Measures

The Intrinsic Motivation Inventory scale (IMI; McAuley et al. 1989) was used to assess participant’s subjective experiences of the letter counting task across four different factors: importance (“I believe participating in this study could be of value to me”), enjoyment (“This study was fun to do”), perceived choice (“I believe I had some choice in participating in this study”), and effort (“I tried very hard on this activity.”). Participants rated their agreement or disagreement of statements on a 7-point Likert Scale ranging from −3 (Strongly Disagree) to +3 (Strongly Agree). The order of items was counterbalanced between participants. Embedded within these items were three attention-check questions that had clear, obvious answers and were used to assess participants’ level of engagement and thoughtfulness. Example items include “Please select ‘Not at all Descriptive (1)’ to answer this item”. Attention was assessed based on the inverse of the error rate. Only participants with no errors were included in the final sample.

3 Results

3.1 Exclusionary Criteria

We excluded participants based on two criteria: their accuracy on the counting task and attention check questions. We excluded participants who did not complete the letter counting task as instructed, as evinced by their accuracy. We assessed accuracy by summing each participant’s total letter and number counts and then divided their total count with the correct count total to create an accuracy ratio score for each participant. We excluded those whose count ratio was more than 10% off the correct total; less stringent exclusion criteria (e.g., 20%) led to similar patterns of results. A total of 124 participants fell outside this range, leaving a total of 210 participants included in our final sample. The frequency of exclusion did not significantly differ between conditions, F(3,330) = .370, p = .774.

To assess how carefully participants were answering questions, we embedded three attention-check questions within the subjective experience items. Only participants who answered all three questions correctly were included in our sample. A total of 27 participants failed at least one of the attention check questions and thus were excluded from analyses. Exclusion did not significantly differ based on condition, F(3,331) = 1.294, p = .274.

3.2 Subjective Experience

To assess participants’ subjective experiences we created aggregate scores for each participant for each of the four subjective experience subscales. Results from a one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of wage condition on participants’ enjoyment, F(1,166) = 4.135, p = .044, and importance of the task, F(1,166) = 4.320, p = .039. Specifically, those in the high payment condition showed significantly more enjoyment (M = 4.45, SD = 1.47) and perceived the task as more important (M = 4.78, SD = 1.48) than those in the low payment condition (M = 3.96, SD = 1.67, and M = 4.27, SD = 1.66, for enjoyment and importance, respectively). Similarly, a marginally significant effect of effort condition on enjoyment emerged F(1,166) = 3.430, p = .066, with those in the unanticipated effort condition showing less enjoyment (M = 4.04, SD = 1.51) than those in the anticipated effort condition (M = 4.49, SD = 1.61). We did not find a significant Wage x Effort interaction on any of the subjective experience measures, all F’s < 1.9, all p’s > .17.

3.3 Positive Endorsement Task

A total of 67 participants (20% of our sample) opted to not complete the additional task. We investigated whether this significantly differed by condition. We found significant differences in those who opted to or not to complete the additional task between conditions, F(3,331) = 8.856, p < .001, with significantly fewer participants opting to complete additional task when offered $.02 (N = 51) compared to when offered $.40 (N = 16). We counted the number of words in each endorsement to examine whether length of endorsement differed based on condition as a proxy measure of participants’ thoughtfulness and effort on the task. The results of a one-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of payment condition on endorsement length F(1,166) = 10.76, p = .001, with those in the high payment condition (M = 17.18, SD = 13.97) writing significantly longer endorsements than those in the low payment condition (M = 12.19, SD = 9.64).

4 Discussion

In the current investigation we manipulated perceptions of effort and monetary compensation and found that, opposite our initial predictions, those offered more monetary compensation rated task as more enjoyable, important, were more likely to write a positive endorsement of the task and wrote longer endorsements compared to those who were offered less money. Similarly, those given accurate descriptions of task length showed marginally more enjoyment of the task. We take these results to mean that, unlike previous research, it appears that fair monetary compensation and accurate study descriptions make individuals enjoy and tasks more, not less. Thus, it appears that MTurk workers are not changing their attitudes to justify inequity but rather are adjusting their attitudes to be consistent with equitable conditions. In other words, when workers feel they are being equitably compensated for their work and provided accurate study descriptions, they show more enjoyment of and perceive the task as more important than when they are not.

While we did not find evidence that MTurk workers were experiencing dissonance, this may be due, in part, to a manipulation failure rather than a lack of dissonance. While our effort manipulation was supposed to induce differing perceptions of effort in our participants, we did not find any differences on the IMI effort subscale between the anticipated and unanticipated effort conditions (a mean of 6.08 compared to 6.01, respectively). Therefore, it may be that our manipulation was not strong enough to induce differing effort perceptions in participants.

4.1 Online: A Special Context?

Our findings do not suggest that individuals are using similar psychological and cognitive processes to buffer their perception of inequity and create consistency between their behavior and attitudes online as they have demonstrated in the real world. It may be that the online context affected how participants dealt with their dissonance. In Festinger and Carlsmith’s (1959) study, none of the participants refused to help out researchers and lie to the next participant compared to the 20% of our participants opted not to complete the additional task. Declining to participate in the additional task may have served as a way for participants to reduce their dissonance (i.e. by changing their behavior). Compared to face-to-face interaction, there are less normative and descriptive pressures online to influence participants’ decisions. Thus, the anonymity afforded to individuals in the online context may buffers individuals from social norms and conformity pressures present in face-to-face interactions, and with these reduced pressures, may have allowed them to address dissonance through a change in their behavior (i.e. stopping their participation by saying no the additional task).

It is likely that these participants, if forced to complete the additional task, would show subjective experience scores much lower than those who opted to complete the additional task. This prediction is corroborated by preliminary evidence coming from the differences between those who did and did not opt to complete the additional task. Those who opted to do the additional task did show higher importance and enjoyment scores than those who did not. Specifically, those who opted to complete the additional task rated their enjoyment as 4.26 compared to 2.47 for those who did not complete the additional task, and rated importance as 4.57 compared to 3.18. Therefore, it may be that those who experienced the most dissonance were also those that ended their participation early and opted not to complete the additional task, skewing our results.

4.2 Implications and Conclusions

In the current investigation we did not find evidence that crowdsourcing workers are experiencing cognitive dissonance. We found that paying participants more and providing them with accurate time descriptions of the tasks resulted in greater enjoyment and increased importance of the task. This, in turn, was associated with doing more work on tasks. It appears that MTurk workers are adjusting their attitudes to be consistent with equitable work conditions not to justify inequitable conditions. These results suggest that dissonance is less of a problem with MTurk workers than previous research would imply.

The results of our investigation have implications for the future of crowdsourcing platforms as a reliable way to gather data. Our findings suggest that participants’ subjective experiences are more positive when they feel they are being compensated equitably, implying that crowdsourcing in its current form is sustainable given that equitable conditions are provided for workers. This sustainability is contingent on researchers’ willingness to create such equitable conditions by providing workers with fair compensation for their participation. Research investigating worker experiences is imperative if crowdsourcing is to remain a valid option for researchers to recruit participants.

References

Aronson, E., Mills, J.: The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group. J. Abnormal Soc. Psychol. 59, 177–181 (1959)

Brawley, A.M., Pury, C.L.S.: Work experiences on MTurk: job satisfaction, turnover, and information sharing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 54, 531–546 (2016)

Busarovs, A.: Ethical aspects of crowdsourcing, or is it a modern form of exploitation. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Adm. 1, 3–14 (2013)

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., Gosling, S.D.: Amazon’s mechanical turk: a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality data? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 6, 3–5 (2011)

Festinger, L., Carlsmith, J.M.: Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. J. Abnormal Soc. Psychol. 58, 203–210 (1959)

Harmon-Jones, E., Mills, J.: An introduction to cognitive dissonance theory and an overview of current perspectives on the theory. In: Harmon-Jones, E., Mills, J. (eds.) Science Conference Series. Cognitive Dissonance: Progress on a Pivotal Theory in Social Psychology, pp. 3–21. American Psychological Association, Washington D.C. (1999)

Lui, B., Sundar, S.S.: Microworkers as research participants: does underpaying Turkers lead to cognitive dissonance? Comput. Hum. Behav. 88, 61–69 (2018)

McAuley, E., Duncan, T., Tammen, V.V.: Psychometric properties of the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory in a competitive sport setting: a confirmatory factor analysis. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 60, 48–58 (1989)

Pittman, M., Sheehan, K.: Amazon’s Mechanical Turk a digital sweatshop? Transparency and accountability in crowdsourced online research. J. Media Ethics 31, 260–262 (2016)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Fritzlen, K., Bilal, D., Olson, M. (2019). Attitude-Behavior Inconsistency Management Strategies in MTurk Workers: Cognitive Dissonance in Crowdsourcing Participants?. In: Stephanidis, C., Antona, M. (eds) HCI International 2019 – Late Breaking Posters. HCII 2019. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1088. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30712-7_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30712-7_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-30711-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-30712-7

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)