Abstract

The term “densification” is often regarded as something negative, as it is linked to traffic congestion, air pollution, problems of environmental vulnerability, but, simultaneously, the “density” in terms of “diversity” of neighbourhoods, types of buildings and public space also makes the city attractive to the multitude of subcultures that inhabit it. Adding dwellings in the right place can improve the existing mix of functions and strengthen or repair the existing identity of a city block or neighbourhood. But adding building mass to a city normally occurs at the expense of open (green) space. The green strategies presented in the paper were developed to green the inner city in a sustainable way, and thus to improve the quality of urban space and living.

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Over the past decade, a renewed notion of the term “heritage” has emerged. It is based on the recognition of the multiple aspects, material and immaterial, which define not only the built environment but also the scale of the naturalistic landscape in which the project can be an opportunity to allow an unprecedented way of enjoying nature. This is particularly true within urban centers where green spaces can assume the connotation of prosthetic spaces capable of favoring the vital functions of those who use it.

The consolidated city while continuing to attract population, continue to lose “healthiness” in the collective spaces often unable to cope with the phenomena of environmental vulnerability (problems related to the impermeability of soils, urban heat islands, etc.), in the closed spaces (often disabling in the face of the variability of users’ needs, and the evolution/involution of their abilities), in the social relations (considering citizens as simple “users” and not active “participants” in the transformation processes of the built environment) [1,2,3].

It is therefore a matter of placing the user at the center in its variability and of considering their relationship with the built environment and the green public space, not only as metric-dimensional but embracing the cognitive and social dimensions too.

Starting from the plurality of different disciplinary sectors, from anthropometry and sociology to psychology, “human experience” and user’s expectations are explored, understood, and systematized [4]. The analysis of the relationship between health and urban design has allowed us to identify design strategies to improve the level of urban livability through integrated densification and greenification solutions.

These strategies concern different levels of interaction between humans-objects-environment that make up the object of the design, where the object can be a technological system, a building component, a domestic instrument, or a service, and the environment is a place or a situation where activities are carried out with the aim of guaranteeing:

-

physical well-being, when the relationship is mainly of a confirmatory and dimensional nature, and is established with systems that need to be manipulated and used through body contact;

-

cognitive-sensorial well-being, since the quality of this kind of interaction depends on the proportional compatibility between the systems and integrates with the sensorial one, which is understood as the appropriateness and coherence of the stimuli emitted by the physical systems with the physiological structures of the individuals.

-

social well-being, understood as the user’s participatory relationship with the transformation of space through creative and innovative projects in which the citizen returns to be the protagonist of local culture and identity.

In this perspective, the design strategies synthetically follow two main directions: the re-appropriation of these places by the citizens and, at the same time, the promotion of their well-being from both a psychophysical and social point of view. The proposed strategies reactivate the traditional alliance between human and natural components as co-acting forces through rebalancing strategies between densification and ecologization (Water Sensitive Urban Design, constructed ground, mat urbanism, drosscape, thick infrastructure, field operations) according to new holistic thinking that produces a “capitalism 4.0” capable of obtaining new value from the re-cyclical processes of the new urban metabolism (startups, maker actions, circular economy creativity, reuse, recycle and creative evolutions) [5].

2 The Green Challenge

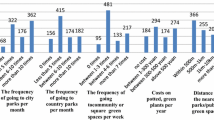

Densification is clearly a step-by-step process affecting major urban centers around the world and in particular the inner cities. The term “densification” is often regarded as something negative, as it is linked to traffic congestion, air pollution, problems of environmental vulnerability, but, simultaneously, the “density” in terms of “diversity” of neighbourhoods, types of buildings and public space also makes the city attractive to the multitude of subcultures that inhabit it. Proximity to others, urban amenities are the most cited reasons for choosing to live in a dense urban environment. Adding dwellings in the right place can improve the existing mix of functions and strengthen or repair the existing identity of a city block or neighbourhood. But adding building mass to a city normally occurs at the expense of open (green) space. Quality of the inner city is the goal, then smart densification must go hand in hand with the qualitative upgrading and quantitative expansion of urban green. Several researches [6,7,8] confirmed that more green space in the inner city is desired, as well as greater diversity in that green space and a better quality of green design and management. This implies that the construction of new dwellings should be accompanied by the provision of extra urban green, to compensate for previously unmet demand. In any case, to welcome the inhabitants that come with these new dwellings, more and better quality urban green is needed. An attractive green infrastructure in the inner city is conditional to the popularity of living in the inner city [9] (Fig. 1).

The presence of greenery in our cities, the quantity of spaces dedicated to it and the maintenance care of the same, are some of the main indicators of civilization and liveability of historic centers and in general it is of great importance to improve the quality of life in the cities. Urban green infrastructures have an important.

Ecological-Environmental Function.

Green Infrastructures will play an increasingly important role in strategies to make cities “climate-proof”. Careful planning and management of green areas would favor the containment of climatic stresses, mitigating the climate itself and the energy requirements for the conditioning of buildings and limiting the effects of extreme events. Furthermore, the plant also acts as a buffer, preserving habitats and contributing to the consolidation of the soil and to the control of surface water flows. There are several virtuous cases in the world [10] and also in Italy, which demonstrate how ecosystem-based adaptation measures, in particular centered on green infrastructures, aimed at strengthening the resilience of ecosystems, are more effective and more convenient than measures possible on the so-called gray infrastructures, built with the aim of facilitating adaptation to climate change but which actually cause other environmental failures [11].

Social and Health Function.

In certain urban areas, in particular near hospitals, the presence of greenery has found an environment that can favor the convalescence of patients, both for the presence of aromatic essences and for the mitigating effect of the microclimate, and also for the relaxing effect produced by the sight of a well-kept green area. The presence of parks, gardens, avenues and squares lined with trees or in any case equipped with green furniture allows us to satisfy an important recreational and social need and to provide a fundamental service to the community, making a city more liveable. Furthermore, the management of the green can favor the creation of jobs [12, 8].

Cultural and Didactic Function.

The presence of greenery is an element of great importance from a cultural point of view, both because it can promote knowledge of botany and more generally of natural sciences and the environment among citizens, and also for its important didactic function (in particular green school) for the new generations. Furthermore, historical parks and gardens, as well as plant specimens of greater age or size, constitute real natural monuments, whose conservation and protection are among the cultural objectives of our community [13].

The existence of natural spaces of the urban context allows man to survive in the completely artificial environment of the city and to improve the health and well-being of citizens. Several researches show that the presence of green areas has consequences about:

Physical well-being, as it improves the quality of sleep (it has an indirect role on the regulation of hormonal functions and therefore on circadian rhythms); reduces the risk of hypertension (Nature has a calming effect, as it slows the heart rate and lowers blood pressure); strengthens the immune system (Nature would have positive effects in the production of Vitamin D and in the activity of NK cells) [14, 15].

Psycho-social well-being, as it reduces stress (spending time surrounded by nature would reduce the amount of cortisol, a hormone linked to stress); improves memory and stimulates mental abilities (immersing yourself for a few days in natural environments helps to concentrate and increase creative thoughts); fights depression (horticulture and gardening, for example, activities to be practiced in the open air, would lead to decreasing tensions and consequently removing states of tension and mood disorders); finally improves social interactions [16,17,18].

3 Green Strategies

The green strategies presented below were developed to green the inner city in a sustainable way, and thus to improve the quality of urban space and living.

Geenway.

In Europe, this term today indicates “paths dedicated to” gentle “and non-motorized circulation, able to connect populations with the resources of the territory (natural, agricultural, landscape, historical-cultural) and with” centers of life “of urban settlements, both in cities and in rural areas” (Italian Greenways Association, 1999). Monumental trees can decorate important locations. Richly planted boulevards, but especially city streets can form a green network that connects squares, parks and green areas inside and outside the city centre. The variety in tree species creates more diversity and reduces vulnerability for species diseases. Trees and grass on roadsides and alongside tram tracks make roads and streets much more attractive and improve the microclimate of the city. The greenery captures fine particles from the atmosphere, absorbs CO2, tempers heat in the summer and restricts hindrance caused by wind. Green streets and roads invite people to walk and cycle and make routes leading to green areas more attractive places. Cyclists and pedestrians benefit from more room on the streets. As a result of more public spaces being situated on boulevards, their recreational value will continue to increase.

Playgrounds.

A child- friendly outdoor space is essential for attractive and complete living surroundings in an inner city. Child-friendliness entails more than just creating a few playgrounds but it encompasses the entire design of the public realm: Broad sidewalks provide informal space for games, skate parks and public sports grounds are useful for adolescents, protected environments for the children, sufficient places to sit improve the quality of the public spaces. The combination of variety in living environments, meeting places and amenities belonging to the inner city will turn the centre into a regular el dorado for children growing up. These green spaces can be effective if placed in correspondence with schools. The greenery belonging to the is an important part of the urban green system and is one of the few open spaces frequented by children in absolute safety. In addition, green areas improve learning, but above all they are a benefit for all those children who cannot enjoy green areas because they live in places where there are no them. Actions are needed to open the schools to their courtyard, to give them back a playful, social and educational role through natural elements, furnishings, structures and programs.

Small Parks Network.

The inners city (of many uropena cities) are crammed with buildings, have no more space for a large metropolitan park, but many small parks can also greenify an inner city. The park strategy aims at creating parks in such a way that a park, however small, is within walking distance of every home. The small parks appointed and differ from each other in form and use can generate a network of green areas and they can contribute crucially to the perception of green in the entire inner city, provided they are well connected.

Green Roofs and Urban Agriculture.

Urban agriculture, is an initiative in which city inhabitants produce food for personal consumption or sale at local markets. In view of the limited space in the inner city, green roofs and facades offer the best opportunities for urban agriculture. Green roofs provide extra ecological quality, capture fine particles and CO2, and provide green scenery (from high-rise buildings) and green recreational (sitting and playing) environments. Moreover, they have a positive effect on the densified inner-city climate and function as water buffers, thus contributing to urban water management. Green roofs and facades also provide excellent locations for realising urban agriculture. Combinations of functions in buildings (e.g. restaurants and schools) and agricultural activities on roofs and facades also have socio-economic value. The challenge is to combine densification with urban greening that directly improves the living environment.

Green Spaces in the Workplace.

The presence of greenery in the workplace improves the performance of the company and the well-being of employees. Work almost completely absorbs a person’s life, moving from home to the office does not always have the opportunity to enjoy green spaces, so this aspect could be integrated within the workplace. Natural light plays a surprisingly important role in improving employee productivity as it increases the creation of melatonin. This hormone regulates people’s sleep-wake cycles and thus makes a material difference to their energy levels. Green spaces is a sound absorbing barrier that reduces noise and therefore promotes concentration, a green workplace improves productivity by 15%.

Therapeutic Gardens.

The Therapeutic Gardens are found mainly in hospitals, nursing homes, mental health centers, for the elderly, for Alzheimer’s patients etc. However, these spaces are not intended only for the sick, as they are also used by the medical staff or by the family members of the hospitalized people, in order to take advantage of all the benefits that the garden offers. Furthermore, there are various types of Therapeutic Gardens, which depending on the type, are inserted in the various contexts (Healing garden, Therapeutic Garden, Restorative Garden, Horticultural Therapy Garden). The Healing garden, the Therapeutic Garden and the Restorative Garden are gardens that are enjoyed “passively”, you benefit from seeing the green. Specifically, among the various types of gardens with therapeutic purposes in which to treat and/or admire plants, the following outdoor green spaces can be mentioned: 1) the healing gardens, which are suitable for all types of people and they foresee a rather passive interaction with nature; 2) the sensory gardens, created to stimulate the five senses so as to bring well-being and joy by increasing the production of endorphins and endogenous substances in the body; 3) rehabilitation gardens to bring patients in the hospital sphere to recovery. Horticultural Therapy Garden, on the other hand, is a garden that is “actively” enjoyed, in fact the patient is involved in gardening activities. The active use of a vegetable garden, that is the activities related to the care of the green, helps to recover the abilities: physical, psychic, emotional and therefore to generate well-being (Fig. 2).

4 More Green Areas + More Densification = More Urban Sustainability

A number of recent publications have drawn attention to the impact on sustainability the process of urbanisation. This process over the last few decades has contributed to a relatively clean, green and quiet living and working environment for many inhabitants of the inner cities. Nevertheless, urbanisation also has had its drawbacks, among them congestion, lack of environmental quality and liveability in cities, insufficient support for urban facilities, and deterioration of biodiversity, landscapes and cultural history values [19], higher consumption of resources, including energy and water. For many European cities, these dynamics result in persistent problems with air, noise and light pollution; insufficient supply of good quality water; aggravation of and vulnerability to the effects of climate change; qualitative and quantitative shortages in biodiversity and urban green per capita; and increasing social polarisation [20]. At the same time, the potential for greater sustainability in cities is enormous, due to advantages of scale for sustainable investments and their concentration of inhabitants, resulting in a solid basis for sustainable solutions in energy supply and urban transport. The overall conclusion is that the “greenification” strategies of the inner city can contribute to a higher level of densification and the sustainability profile of the cities.

More demographic diversity due to greater satisfaction with the living environment and greater greenification of the inner city entails:

More Physical Activity.

The adults and children will have more possibilities for physical activity, which in combination with relatively less car use will lead to more years of healthy living. Ambitious urban green development induces physically active behaviour. More playgrounds will be created through strategies for urban greening and existing playgrounds will be used more intensively. Examples of relevant elements in a urban design include lanes with separate walk ways and cycle paths, the establishment of attractive green areas and the reduction of barriers by providing extra connections such as bridges for slow traffic.

More Leisure Facilities and Increase of the Market Value of Houses.

M. Jacobs said: “to generate exuberant diversity in a city’s streets and districts there must be a sufficiently dense concentration of people, for whatever purpose they may be there” [21, 22]. Furthermore, diversity and flexibility of space for leisure facilities and services should allow for easy adaptation to actual needs in future and at different times of the day. Finally, the densification of greenery, population and services also affects the market value of housing. For many blocks of buildings their proximity to urban green improves significantly their market value.

More Employment in Service Activities.

A denser inner city leads to a higher demand for services, such as shops, restaurants, hairdressers, and the financial and administrative services that in turn support these companies. Employment and added value per square metre will increase as a result of urban densification and the resulting increase in inner city inhabitants.

Less Heat Islands Effects.

Less heat islands effects and less noise level. The heat islands effects seems to be largely compensated for by an increase in shade cast by higher buildings and urban trees; while e the effects of busier traffic can be countered by buildings that act as acoustic screen and the assumed higher importance of public transport, walking and cycling as means of transport.

Less Energy Consumption.

Densification has the added benefit of contributing to a more compact urban form , more clustering within the urban morphology leads to more energy efficiency as well. Further, the district energy networks will become more efficient and profitable because they will supply energy to a greater number of buildings and heat exchange between buildings will be possible.

References

Friedman, Y.: Pour l’Architecture Scientifique. Pierre Belfond: Paris, France (1971)

Habraken, N.J.: De Dragers en de Mensen; Scheltema en Holkema. Amsterdam (1962)

Cellucci, C.: Adaptive retrofitting strategies for social and ecological balance in urban Mediterranean area. SMC J. Sustain. Mediterr. Constr. 10, 100–104 (2019)

Schiaffonati, F., Mussinelli, E., Gambaro, M.: Tecnologie dell’Architettura per la Progettazione Ambientale. Techne. J. Technol. Archit. Environ. 1, 48–53 (2011)

Kaletsky, A.: Capitalism 4.0: the birth of a new economy. In: The Aftermath of Crisis, Perseus, New York (2010)

Vargas-Hernández, J.G., Pallagst, K., Zdunek-Wielgołaska, J.: Urban green spaces as a component of an ecosystem. In: Handbook of Engaged Sustainability. Springer (2018)

Abraham, A., Sommerhalder, K., Abel, T.: Landscape and wellbeing: a scoping study on the health-promoting impact of outdoor environments. Inter. J. Publ. Health 55(1), 59–69 (2010)

Lee, A.C.K., Maheswaran, R.: The health benefits of urban green spaces: a review of the evidence. J. Publ. Health 33(2), 212–222 (2011)

Kuo, F.E., Bocacia, M., Sullivan, W.C.: Transforming inner-city neighbourhoods: trees, sense of safety, and preference. Environ. Behav. 30(1), 28–59 (1998)

FAO 2018: Forests and sustainable cities Inspiring stories from around the world. FAO, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2018)

EU 2016: Supporting the Implementation of Green Infrastructure Final Report. European Commission, Directorate-General for the Environment ENV.B.2/SER/2014/0012 Service Contract for “Supporting the Implementation of Green Infrastructure”. Rotterdam (2016)

Irvine, K.N., Warber, S.L.: Greening healthcare: practicing as if the natural environment really mattered. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 8(5), 76–83 (2002)

Kaplan, R., Kaplan, S.: The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1989)

Lachowycz, K., Jones, A.P.: Green space and obesity: a systematic review of the evidence. Obes. Rev. 12(5), e183–e189 (2011)

Hartig, T., Mang, M., Evans, G.W.: Restorative effects of natural environment experiences. Environ. Behav. 23(1), 3–26 (1991)

Engel, G.L.: The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977(196), 129–136 (1977)

World Health Organization. World Health Organization Definition of Health (1998). https://www.who.ch/aboutwho/definition.htm . Accessed 8 Nov 2020

Alberti, M., Marzluff, J.M.: Ecological resilience in urban ecosystems: linking urban patterns to human and ecological functions. Urban Ecosyst. 7(3), 241–265 (2004)

PBL Balans van de Leefomgeving: The Hague, Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving (Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (2010)

EEA: The European Environment, State and Outlook 2010, Urban Environment. Copenhagen, European Environmental Agency (2010)

Jacobs, J.: The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House, New York (1961)

Tillie, N., et al.: Rotterdam, People Make the Inner City. Cressie Communication Services, Rotterdam (2012)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Cellucci, C., Di Sivo, M. (2021). Green Densification Strategies in Inner City for Psycho-Physical-Social Wellbeing. In: Ahram, T., Taiar, R., Groff, F. (eds) Human Interaction, Emerging Technologies and Future Applications IV. IHIET-AI 2021. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 1378. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74009-2_45

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74009-2_45

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-73270-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-74009-2

eBook Packages: Intelligent Technologies and RoboticsIntelligent Technologies and Robotics (R0)