Abstract

In online settings, people often face inconsistent or conflicting information about a target of judgment. To make an accurate judgment, they need to determine which information is most relevant, reliable, and trustworthy and how to incorporate it into their judgment making processes. In this paper, we call this the second-order judgment problem—evaluating the value of the information on the target of judgment before making judgments. Extending previous research on online impression formation [1], this study examined the impact of perceived social closeness between the target person whose personality is to be judged and those who provide the information about that person (e.g., comments), which is, in particular, in conflict with the information generated by the target person (e.g., online profiles) on impression formation. To this end, a web-administered experiment was performed, where participants were asked to judge the personality of a target person after reviewing the person’s Facebook page, which had conflicting information. The results showed that the information generated by distant others was more influential on judgment making than that generated by close others, confirming that perceived social closeness functioned as a critical cue for judging the value of the available information. The current findings provide an important implication for the design of the interface of social media: the method of presenting the information about the available information can alter the allocation of judgment makers’ attention, and thereby, final judgments.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Second-order judgment problems

- Information incompatibility

- Judgment formation

- Perceived social relationship

- Social media

1 Introduction

The information provided by others, who presumably better know about the target of judgment, is useful in judgment making, in particular, in online settings [2–4]. For example, online shoppers look at the reviews submitted by others who have already used the products before they make purchases. However, information about the target of judgment is often inconsistent, or even conflicting, because it is created by multiple sources with different interests, tastes, and perspectives. Online sellers always advertise their products by demonstrating their benefits, but product reviews may not be as positive as advertised. Even for the best-rated products, some people may still complain and leave negative reviews. If inconsistent or conflicting information is the only available information about the target of judgment, judgment makers have to determine which information (or its sources) is more relevant, reliable, and trustworthy, and therefore, to be incorporated into their judgment-making processes. Put simply, judgment makers need to judge the informational value of the information on the target of judgment, which we shall call the second-order judgment problem in this paper.

Given that online environments are characterized by open-participation, diversity, and decentrality [5], it is reasonable to expect that there would be diverse opinions and views on the same objects. Therefore, inconsistent and conflicting information is very common, and online users frequently face second-order judgment problems. From this perspective, the current study explores the strategies people adopt to cope with information incompatibility in making judgments online. In particular, this study extends previous research on online impression formation, where the task is to judge the personality of a target person based on his/her conflicting online profile information [1]. Whereas previous research focused on the authorship of the information as a critical factor for judging the informational value, this study emphasizes the perceived relationship between the target and the creator of the information, as well as the authorship of the information. To this end, we conducted a web-administrated experiment in which participants were to judge the personality of target people based on their online profile information.

This paper is organized as follow: The next section briefly reviews previous literature on online impression formation and establishes research hypotheses. The following two sections—Methods and Results—describe the participants, the experiment design, the study procedure, and reports the results of statistical analysis. The final section discusses the theoretical and practical implications of the current findings and also suggests the directions of future research.

2 The Second-Order Judgment Problems in Social Media

2.1 The Impacts of the Authorship on Information Trustworthiness

Judgment formation based only on available information, as opposed to complete and perfect information, has long been studied, even before the advent of the internet. Perhaps, the first theoretical approach would be Spence’s job-market signaling model published in 1973 [6]. The model assumes that employers need to make a correct judgment about job applicants (e.g., their skills and expertise) based on the information provided by the applicants themselves and little else. In that case, job applicants are incentivized to provide false information about themselves to get hired or for higher wages. For this reason, employers need to carefully review all the provided information, and further, determine which information should be weighted more instead of considering all the information equally. Spence’s cost-benefit analysis of informational values suggests that the information that costs less to create (i.e. easy to manipulate) should be excluded from consideration.

Spence’s signaling model has been further elaborated and successfully applied to impression management and formation in online contexts [2]. On one hand, early research on online impression management has found that people tend to construct and selectively present their positive images, as job applicants would do in job markets. For example, users in online dating sites manage their online profile to appear more likable or competent than they are [7]. Furthermore, they often engage in deceptive communication to compare favorably with others [8]. On the other hand, the literature on online impression formation suggests that people want to know others’ authentic identities, as employers would do in job interviews. In the case of online dating sites, users have to decide whether to pursue the relationship by looking at any information available on the sites. To make a correct judgment of others, the users pay attention to information that reduces uncertainty about others’ offline authentic identities and personalities [8, 9]. Given the tension between impression management and impression formation, judging a target’s authentic identity requires the correct evaluation of the informational values of information about the target before making a judgment. Spence’s signaling model would suggest that the information that costs less to create in the online environment should be carefully examined and excluded, if necessary, in judgment making processes [2].

Previous research on impression formation in social media has found that the value of the information about the target of judgment is perceived differently depending on the authorship of the information [1]. Specifically, the information generated by the target him or herself (i.e., self-generated information) is unlikely to be perceived as reliable because such information tends to be biased in favor of the target [8, 10]. For instance, a target can easily self-present a heavy community service-oriented image after a few clicks of the mouse on his/her online profile. The target would not display any information about him or herself drinking at a party or procrastinating at work to maintain the self-image in a positive light. On the other hand, the information generated by others than the target (i.e. other-generated information) is perceived as more objective and trustworthy. This is because other-generated information is not easily controlled or manipulated by the target, and thus, more “costly” in Spence’s [6] term. The example includes a personalized message such as the following: “Jane, thank you so much for your consistent commitment to providing a service at our retirement home.” Such an other-generated comment would have clearly required significantly greater offline time and effort than can be assumed from self-generated information. Therefore, people tend to rely on other-generated information more than self-generated information, when the two kinds of information are incompatible [11].

From this perspective, the authorship of information is expected to play as a critical role in the second-order judgment problems. More specifically,

H1: Other-generated information will have greater influences on judgment making than self-generated information in the presence of information incompatibility.

2.2 The Impacts of Social Closeness on Information Trustworthiness

As its name itself implies, a major function of social media is to build and maintain social relations among users, leading to the emergence of unprecedentedly large-scale social networks [12]. In social networks, individuals are connected in pairs by social ties. Some pairs are connected by “strong” ties, whereas others are loosely connected [13, 14]. Strong ties imply frequent interactions, long-lasting relationships, sharing mutual friends, common affiliations, and social closeness above all [15]. These social ties among users are recognizable in social media because the networked communication platform allows individuals to communicate with all of their social pairs in one place (e.g. individuals’ profiles). For example, both the comments generated by the target’s best friends and those generated by someone who just met the target are available on the target’s profile page.

Previous research on interpersonal relationships implies that people would perceive the same information about a target differently depending on the information providers’ relationship with the target. Studies have found that close others are motivated to deepen and intensify the experience of closeness while distant others concern the formation and stability of long-term relationship [16, 17]. Thus, close others tend to share thoughts, information, and feelings favorable to their communication partners. On the other hand, distant others involve boundary settings and developments of a sense of self and autonomy [16]. Having experienced this communication behavior with their close and distant others, people may perceive a target’s close others’ comments about the target as more subjective and emotional, whereas distant others’ comments as more objective and informational.

Given the role of social closeness in message perception and the feature of social media platform, the dichotomy between selves and others appears to be too simple to fully capture judgment making with conflicting information in social media. The present study suggests that social closeness may play a critical role in the second-order judgment problems (Fig. 1). Based on the literature, judgment makers would think that the information generated by distant others reflects more objective and accurate offline identity about the target than that generate by close others. Thus, judgment makers would be more influenced by information generated by others who have relationships that are relatively independent of the target person than that generated by close others in the judgment-making process.

More specifically, the present study hypothesized that.

H2: The information generated by distant others will have a greater influence on judgment making than that generated by close others in the presence of information incompatibility.

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

Participants (N = 88; 20 male and 68 female) were undergraduate students from a university in California who volunteered to participate in the study in exchange for extra course credit or in partial fulfillment of a class research requirement. The sample identified their ethnic background to be 58.0 % Caucasian and 42.0 % others. Facebook use was assessed by the item “How often do you use Facebook.” The present study only included participants who use Facebook everyday in order to control their familiarity of Facebook. Thus, 11 participants (14.1 %) who did not use Facebook everyday were excluded.

3.2 Procedure

Main Study. An experiment was carried out to test these hypotheses. The experiment started with an informed consent form where the participants were briefly introduced to the study. After participants understood that their responses were anonymous, they viewed the mock profile of the target person, Chris Kim. After viewing the profile, they rated their impressions of Chris Kim. A total of 2 stimuli were created with mock-up Facebook profiles.

Stimuli and Design. This study focused specifically on measurement of extraversion in social media setting in testing for impression formation [1]. Extraversion is among the Big Five personality dimensions along with experience, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and neuroticism [18, 19]. In addition to its wide empirical support as a personality dimension, extraversion is also often extracted and assessed from social media profiles [20]. Prior studies have found that online presentations of extraversion in social media profiles differ from online presentations of introversion in the amount of information displayed and the nature of content displayed [21, 22].

The experiment randomly assigned participants each to two conditions. Both conditions included conflicting information of a target person between self-(e.g., the target claimed to be an introvert) and other-(e.g., the other suggested the target was extrovert) generated comments in a mock-up Facebook profile (H1). The difference between the two conditions was in the social relationships between the target person and others: close others for one condition and distant others for the other condition (H2). Participants were then asked to make judgments of the target person. In essence, this design allowed for the testing of two hypotheses at the same time.

Manipulation Check. To determine that the stimulus statements induced intended social relationships, a pretest was administered to undergraduate students (N = 25) from a university in California, who were independent from the main study participants. Participants were asked to evaluate the degree of closeness in a relationship between the target and the target’s Facebook friends after reading a set of descriptive statements about the target. They each rated two conditions, close others and distant others. The sample items for the close others’ statements included “hey, call me when you hear where the partyz at… you will hear before I do lol” The statements in the distant others condition included “hey it was great meeting you last night! I think you drank twice as much as me, but still managed to be the life of the party!!” Participants responded to items such as “This person and others who comment on her Facebook are close to each other.”

A paired-sample t test showed that the statements produced differences in the degree of closeness of social relationships. The close others’ statements had significantly greater scores on closeness in relationship, M = 3.56, SD = 0.77, than did the distant others’ statements, M = 2.08, SD = 0.86, t(24) = 6.59, p <.001.

Measures. The dependent variable of extraversion was assessed via an online questionnaire. The experiment used a subscale of the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) [19] that was adapted for judgment makers [23]. Scales included items such as “This person likes to have a lot of people around,” and “This person really enjoys talking to people.” Participants responded to these items on five-interval Likert-type scales, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Reliability among items was acceptable, Cronbach’s α = .81.

Time to complete the survey was also measured in order to exclude insincere response. Manipulation checks provided the mean time for judgment makers in reading Chris’s Facebook profile and perceiving the relationship between Chris and her friends (M = 57.79 (seconds per one stimulus)). Considering that participants were asked to respond to 24 items (taking two to three seconds per item) after viewing the Facebook profile, those who spent less than two minutes were excluded. Thus, a total of 64 participants (72.73 %) were included in the analysis.

Data Analysis. In order to compare the mean of conditions, one-sample t test and an independent sample t test were performed for the experiment. The one-sample t test was used to test whether participants perceived the target as an extravert. Since self-generated information indicated that the target is introvert and other-generated information indicated the target is extrovert, greater than neutral (value = 3) assessments of extroversion can be considered as judgment makers’ perception of target extraversion. An independent sample t test allowed the comparison of the target’s mean extraversion between intimate relationship and less intimate relationship conditions.

4 Results

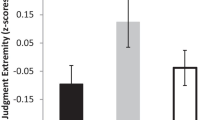

Hypothesis 1 predicted that judgment makers attribute other-generated information with greater weight than self-generated information. It was supported by one sample t test showing that judgment makers perception of extraversion of the target (M = 3.40, SD = 0.47) was significantly higher than 3, t(63) = 6.80, p < .001. The results suggest that although the target described themselves as introvert, judgment makers tended to judge the target as extravert in accordance to others’ description of the target as an extravert. The reason for this is because judgment makers attributed other-generated information with greater weight than self-generated information.

The second hypothesis was that information about a target generated by distant others will have more influence on judgment of the target’s impression than information about the target generated by close others. The result also supported the Hypothesis 2, showing that the perception of extraversion of the target in the distant other condition (M = 3.52, SD = 0.46) was significantly higher than that of the target in close other condition (M = 3.29, SD = 0.47), t(62) = 2.02, p < .05. This indicates that judgment makers attributed distant others’ comments about the target with greater weight than close others’ comments about the target.

Effect size was also measured in order to look at the amount of variance explained. Although the mean difference of two conditions seemed small, the results showed that different relationships had medium effects on judgment makers’ perception of extraversion of the target, η 2 = .061 [24]. This indicates that social relationships between the target and others effectively explain judgment makers’ impression formation of the target.

5 Discussion

This study found that judgment makers attributed other-generated information about a target person with greater weight than self-descriptions. In addition to the authorship of information about the target, participants valued distant others’ comments more than close others’ comments. The findings suggested that participants used the perceived social closeness between the target person and the authors of information as meta-information to judge the trustworthiness of the information in social media.

The current study extends previous research by incorporating the perceived social closeness between the authors of information and the target person to whom the information refers as an important moderator into the model. Although previous research explained well the impact of the authorship of information in social media, it did not consider the major feature of social media, social tie-based platforms, and thus did not adequately capture judgment making with conflicting information in social media. By applying social network features to the existing model, the present study confirmed that perceived social closeness functioned as a critical cue for judging the trustworthiness of the available information and that final judgments varied depending on whether and in what way the social closeness was perceived.

One potential concern with this study is the small mean difference of close and distant others’ influence on extraversion judgment. Although the different relationships had medium effects on judgment maker’s perception, the small mean difference cannot be considered as trivial. However, recent research suggested that extraversion is cued from observable dynamic behavior, such as frequency of posting messages and quick responses than static sources [1, 25]. Thus, the small difference of extraversion judgment could be considered as less sensitive to variation in Facebook pages. On the other hand, one can consider the case of diluting of influence of distant others’ comments. When judgment makers think close others barely need to exaggerate or lie about a target, such as the extraversion in this study, some judgment makers can rely more heavily on the close others’ comments because the information could be more accurate. Thus, if judgment makers have to make attractiveness judgments of a target, which can be more favorably generated by close others, the effects of distant others’ comments can be increased.

6 Conclusions

The abundance of information does not immediately result in the accurate judgment or evaluation. Instead, it may require additional efforts to judge the informational value of the available information. If it is the case, as the volume of available information increases, the amount of effort required will increase accordingly. This, in turn, implies that information systems that merely contain huge amounts of information may not be useful at all, no matter how much information they have. Rather, information systems should be designed to solve the second-order judgment problems. In an online market, such system designs are well established to help consumers’ judgment-making processes. For example, Netflix recommends videos that might be relevant to a specific customer’s interest rather than displays all the videos that are available. In the case of Amazon, if a user values customer ratings, the search result page shows the list in order of highly reviewed products. The recommendation systems in Netflix and Amazon not only save customers’ time and effort but encourage informed decisions by providing valuable information specific to each customer.

In the era of the deluge of social media, with the availability of too much information, it is getting more difficult to accurately judge people. As social media is used more and more in everyday life ranging from personal (e.g. online dating) to professional (e.g. the job market), there is increasing friction between impression management and impression formation. In this sense, social media interface designs (e.g., whether or not the information about the available information are provided) can help users effectively seek and process information which will be enable them to eventually make informed judgments and decisions.

References

Walther, J.B., Van Der Heide, B., Hamel, L.M., Shulman, H.C.: Self-generated versus other-generated statements and impressions in computer-mediated communication a test of warranting theory using Facebook. Commun. Res. 36, 229–253 (2009)

Donath, J.: Signals in social supernets. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 13, 231–251 (2007)

Walther, J.B., Liang, Y.J., Ganster, T., Wohn, D.Y., Emington, J.: Online reviews, helpfulness ratings, and consumer attitudes: an extension of congruity theory to multiple sources in web 2.0. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 18, 97–112 (2012)

DeAndrea, D.C., Van Der Heide, B., Easley, N.: How modifying third-party information affects interpersonal impressions and the evaluation of collaborative online media: influence of third-party content on impressions. J. Commun. 65, 62–78 (2015)

Dahlberg, L.: The internet and democratic discourse: exploring the prospects of online deliberative forums extending the public sphere. Inf. Commun. Soc. 4, 615–633 (2001)

Spence, M.: Job market signaling. Q. J. Econ. 87, 355–374 (1973)

Ellison, N., Heino, R., Gibbs, J.: Managing impressions online: self-presentation processes in the online dating environment. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 11, 415–441 (2006)

Toma, C.L., Hancock, J.T., Ellison, N.B.: Separating fact from fiction: an examination of deceptive self-presentation in online dating profiles. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 34, 1023–1036 (2008)

Gibbs, J.L.: Self-presentation in online personals: the role of anticipated future interaction, self-disclosure, and perceived success in internet dating. Commun. Res. 33, 152–177 (2006)

Walther, J.B.: Computer-mediated communication impersonal, interpersonal, and hyperpersonal interaction. Commun. Res. 23, 3–43 (1996)

Walther, J.B., Parks, M.R.: Cues filtered out, cues filtered in: computer-mediated communication and relationships. In: Knapp, M., Daly, J. (eds.) Handbook of Interpersonal Communication, pp. 529–563. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks (2002)

Kwak, H., Lee, C., Park, H., Moon, S.: What is Twitter, a social network or a news media? In: Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web, pp. 591–600. ACM, New York (2010)

Wasserman, S., Faust, K.: Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1994)

Granovetter, M.S.: The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 78, 1360–1380 (1973)

Burt, R.S.: Neighbor Networks: Competitive Advantage Local and Personal. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2011)

Ben-Ari, A.: Rethinking closeness and distance in intimate relationships: are they really two opposites? J. Fam. Issues 33, 391–412 (2012)

Birtchnell, J., Voortman, S., DeJong, C., Gordon, D.: Measuring interrelating within couples: The Couple’s Relating to Each Other Questionnaires (CREOQ). Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 79, 339–364 (2006)

John, O.P., Srivastava, S.: The big five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin, L.A., John, O.P., Pervin, L.A. (eds.) Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, pp. 102–138. Guilford Press, New York (1999)

McCrae, R.R., Costa, P.T.: The five-factor theory personality. In: John, O.P., Robins, R.W., Pervin, L.A. (eds.) Handbook of Personality, Third Edition: Theory and Research, pp. 139–153. Guilford Press, New York (2008)

Utz, S.: Show me your friends and i will tell you what type of person you are: how one’s profile, number of friends, and type of friends influence impression formation on social network sites. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 15, 314–335 (2010)

Marcus, B., Machilek, F., Schütz, A.: Personality in cyberspace: personal web sites as media for personality expressions and impressions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 90, 1014–1031 (2006)

Krämer, N.C., Winter, S.: Impression management 2.0: the relationship of self-esteem, extraversion, self-efficacy, and self-presentation within social networking sites. J Media Psychol. 20, 106–116 (2008)

Hancock, J.T., Dunham, P.J.: Impression formation in computer-mediated communication revisited an analysis of the breadth and intensity of impressions. Commun. Res. 28, 325–347 (2001)

Cohen, J.: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. L. Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale (1988)

Tong, S.T., Van Der Heide, B., Langwell, L., Walther, J.B.: Too much of a good thing? the relationship between number of friends and interpersonal impressions on Facebook. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 13, 531–549 (2008)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Park, M., Oh, P. (2016). Judgment Making with Conflicting Information in Social Media: The Second-Order Judgment Problems. In: Meiselwitz, G. (eds) Social Computing and Social Media. SCSM 2016. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 9742. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39910-2_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39910-2_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-39909-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-39910-2

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)