Abstract

The theory of autopoiesis, i.e., self-referentiality in the operation of the system, provides us with a production rule for change in the structure of the network. Using information theory, a model system is developed to study the relative likelihood of “dynamic” transitions: various senses of “irreversibility” (“emergence”, and “path dependency”) are disinguished. A test for “path dependency” is applied to two sets of empirical data which supposedly reflect historical discontinuities: the budget of theFraunhofer Gesellschaft, and the citation network among AIDS research related journals. The model for the interaction between self-referential developments and goal-referential boundary conditions is further specified, using the example of technological trajectories and selection environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes and references

M. Hesse,Revolutions and Reconstructions in the Philosophy of Science, Harvester Press, Sussex, 1980, p. 87.

M. S. Granovetter, The Strength of Weak Ties,American Journal of Sociology, 78(1973) 1360–80.

“Such linkage generates paradoxes: weak ties, often denounced as generative of alienation (Wirth, 1938) are here seen as indispensable to individuals' opportunities and their integration into communities; strong ties, breeding local cohesion, lead to overall fragmentation.”Ibid.

M. Callon, B. Latour, Unscrewing the Big Leviathan, In:K. Knorr-Cetina, A. Cicourel,Advances in Social Theory and Methodology. Toward an Integration of Micro-and Macro-Sociologies, Routledge & Kegan Paul, Boston etc., 1980, p. 289. See also:M. Callon, Some elements of a sociology of translation: domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St Brieuc Bay, In:J. Law (Ed.),Power, Action and Belief. A New Sociology of Knowledge, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, etc., 1985, pp. 196–233;M. Callon, J. Law, A. Rip,Mapping the Dynamics of Science and Technology, Macmillan, London, 1986.

M. Callon, J.-P. Courtial, W. A. Turner, S. Bauin, From translations to problematic networks An introduction to co-word analysis,Social Science Information 22(1983) 191–235.

H. R. Maturana,Erkennen: Die Organisation und Verkörperung von Wirklichkeit, Braunschweig, 1982;F. Varela, L'auto-organisation: de l'apparence au mécanisme, In:P. Dumouchel, J.-P. Dupuy (Eds.),L'auto-organisation: de la physique au politique, Paris, 1983;N. Luhmann,Soziale Systeme, Grunrisz einer allgemeinen Theorie, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a.M., 1984.

R. S. Burt,Toward a Structuralist Theory of Action, Academic Press, New York, etc., 1982

N. Luhmann,Die Wissenschaft der Gesellschaft, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a.M., 1990.

. pp. 320f. Consequently,Hesse's criteria of “coherence” and “consistency” are replaced with the criterion of “complexity,” i.e., a more precise specification, and one with capacity to generate new options within the system.

See also:W. Krohn, G. Küppers,Die Selbstorganisation der Wissenschaft, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a.M., 1989. These authors position the self-referentiality of the system in the research system, which is in this sense historical by its very nature, since it is defined in terms of researchers and research groups. However, the question remains whether the research system is evolutionary.

See:S. Woolgar,Science. The Very Idea, Sage, Beverly Hills, etc., 1988. In my opinion, the relativist position is a consequence of taking the social system of science as a reference and not the (cognitive) communication system. See also my comments onKrohn andKüppers (op. cit.) in note 10 above.

“Die Ausdifferenzierung von Wissenschaft führt, mit anderen Worten, zu einem Doppelzugriff der Gesellschaft auf Wissenschaft—nämlich von auszen und von innen, über andere Funktionssysteme und über die Sonderautopoiesis des Wissenschaftssystems selber. (...) Während man den Funktionsbezug mit dem Modell eines selbstreferentiell geschlossenes Systems beschreiben musz, würde es, wenn man nur auf Leistungsbeziehungen abstellen will, genügen, ein Input/Output-Modell zugrunde legen. (...) In diesem Sinne läszt sich die Dynamik der modernen Gesellschaft nur polykontextural, das heiszt: nur aus der Sicht verschiedener System/Umwelt-Differenzierungen begreifen.”Luhmann,. pp. 355 ff. Hence, for example, at p. 340: “Die Ausdifferenzierung verändert auch das System der Gesellschaft, in dem sie stattfindet, und auch dies kann wiederum Thema der Wissenschaft werden. Das allerdings ist nur möglich, wenn man ein entsprechend komplexes systemtheoretisches Arrangement zugrundelegt.”

See also:L. Leydesdorff, The scientometrics challenge to science studies,EASST Newsletter 9(1990a, No. 1) 7–11;L. Leydesdorff, Relations among science indicators or more generally among anything one might wish to count about texts, I. The static model,Scientometrics, 18(1990b) 281–307;L. Leydesdorff, Relations among sciece indicators or more generally predictions on the basis of anything one might know about texts, II. The dynamics of sciece,Scientometrics, 19(1990c) 271–96;L. Leydesdorff, The prediction of science indicators using information theory,Scientometrics, 19(1990d) 297–324;L. Leydesdorff, The static and dynamic analysis of network data using information theory.Social Networks, 13 (1991) 301–345.

C. E. Shannon, A mathematical theory of communication,Bell System Technical Journal, 27 (1948) 379–423 and 623–56;H. Theil,Statistical Decomposition Analysis, North Holland, Amsterdam, etc., 1972;K. Krippendorff,Information Theory. Structural Models for Qualitative Data, Sage, Beverly Hills, etc., 1986.

R. R. Nelson, S. G. Winter, In search of a useful theory of innovation,Research Policy, 6 (1977) 35–76.

J. Gleick,Chaos, Penguin, New York, etc., 1987.

Nelson, Winter,, 6 (1977) p. 48.

p. 61.

Van den Belt andRip noted that the implication of the purposefulness of the stochastic process on the variation side refers to Lamarck rather than to Darwin in terms of evolution theory. See:H. Van den Belt, A. Rip, The Nelson-Winter-Dosi model and synthetic dye chemistry, In:W. Bijker et al. (Eds),The Social Construction of Technological Systems, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1987.

Nelson, Winter, p. 64.

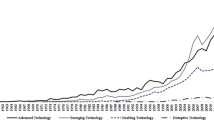

Among others:G. Dosi, Technological paradigms and technological trajectories,Research Policy, 11 (1982) 147–62;D. Sahal, Technological guideposts and innovation avenues,Research Policy, 14 (1985) 61–82;P. P. Saviotti, J. S. Metcalfe, A theoretical approach to the construction of technological output indicators,Research Policy, 13 (1984) 141–51;P. P. Saviotti, Information, variety and entropy in technoeconomic development,Research Policy, 17 (1988) 89–103.

W.B. Arthur, Competing technologies, In:G. Dosi et al. (Eds),Technical Change and Economic Theory, Pinter, London, 1988, pp. 590–607.

P. David, Clio and the economics of QWERTY,American Economic Review. Proceedings 75 (1985) 332–7.

Where a linear system may have a limiting “set of fixed points” in the distribution for large numbers, a system with increasing returns allows for several such sets of fixed points. See:W. B. Arthur, Positive feedbacks in the economy,Scientific American, February 1990, 80–5.

Ibid., Where a linear system may have a limiting “set of fixed points” in the distribution for large numbers, a system with increasing returns allows for several such sets of fixed points. See:W. B. Arthur, Positive feedbacks in the economy,Scientific American, February 1990, p. 81.

In systems dynamics the self-referential system is opposed to the goal-referential system, which has feedbacks in order to keep the system at a certain stage. See also:R. Hanneman,Computer-Assisted Theory Building: Modeling Dynamic Social Systems, Sage, Newbury Park, etc., 1988.

R. K. Merton, The Matthew effect in science,Science 159 (5 January 1968) 56–63.

J. Weyer, ‘Reden über Technik’ als Strategie sozialer Innovation. Zur Genese und Dynamik von Technik am Beispiel der Raumfahrt in der Bundesrepublik, In:M. Glagow, H. Willke, H. Wiesenthal (Eds),Gesellschaftliche Steuerungsrationalität und partikulare Handlungsstrategieen, Centaurus-Verlagsgesellschaft, Pfaffenweiler, 1989, pp. 81–114.

M. Callon, Réseaux Technico-Economiques et Irreversabilité, In:R. Boyer (Ed.),Figures de l'irreversibilité en économie, Paris: EHESS, 1990.

, p. 14.

See for an introduction to information theory:Theil 1972.

Theil 1972.

Again the two base for the logarithm will allow us to compute the information in terms of bits.

H. Theil,Applied Economic Forecasting, North Holland, Amsterdam, 1966;Leydesdorff 1990d.

Callon 1985,, pp. 205 ff.

Cf.Leydesdorff 1990d.

M. Maruyama, The second cybernetics; deviation-amplifying mutual causal processes,American Scientist, 51 (1963) 164–79.

See for an introduction:I. Bradley, R. L. Meek,Matrices and Society. Matrix Algebra and Its Applications in the Social Sciences, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1986.

See also:Theil 1972,.

See for the problem of propagation:J. Pearl,Probabilistic Reasoning and Artificial Intelligence: Networks of Plausible Inference, Morgan Kaufman, San Mateo, Cal., 1988.

See for the treatment of the non-occurrence of a category in one instance, while it belongs to the defined universe:Leydesdorff 1990c,,EASST Newsletter 9(1990a, No. 1) 7–11.

H.-W. Hohn, V. Schneider, Path-dependency and critical mass in the development of research and technology: A focused comparison. Paper presented at theXIIth World Congress of Sociology, Madrid, July 9–13, 1990.

H.-W. Hohn, U. Schimank,Konfikte und Gleichgewichte im Forschungssystem: Akteurkonstellationen und Entwicklingspfade, in der Staatlich finanzierten auszeruniversitären Forschung, Campus, Frankfurt a.M., 1990.

R Shilts,And the Band Played On, St. Martin's Press, New York, 1987.

On clinical evidence, e. g.,A. Rubinstein et al.,Journal of the American Medical Association 249(1983) 2350–6. Gallo's group reported evidence for presence of the viral genomen of HTLV-I or an HTLV-I variant in 2 of 33 AIDS patients in:E. P. Gelman et al.,Science 220(1983) 862–5. See also: The chronology of AIDS research,Nature, 326 (2 April 1987) 435–6.

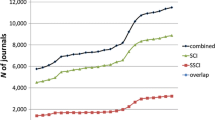

D de Solla Price, Networks of scientific papers,Science, 149 (1965) 510–5;E. Garfield, Citation analysis as a tool in journal evaluation,Science, 178(1972) 471–9;L. Leydesdorff, Various methods for the mapping of science,Scientometrics 11(1987) 291–320.

E. Garfield et al., Science Citation Index, ISI, Philadelphia, 1974.

Leydesdorff 1990d,.

See also:Luhmann,.Weyers,op. cit., note 29. ‘Reden über Technik’ als Strategie sozialer Innovation. Zur Genese und Dynamik von Technik am Beispiel der Raumfahrt in der Bundesrepublik, In:M. Glagow, H. Willke, H. Wiesenthal (Eds),Gesellschaftliche Steuerungsrationalität und partikulare Handlungsstrategieen, Centaurus-Verlagsgesellschaft, Pfaffenweiler, 1989, pp. 81–114.

Maruyama 1963,.Arthur 1990,op. cit., note 25. Where a linear system may have a limiting “set of fixed points” in the distribution for large numbers, a system with increasing returns allows for several such sets of fixed points. See:W. B. Arthur, Positive feedbacks in the economy,Scientific American, February 1990, 80–5.

To this end, one may wish to build on measurement in terms of variety and information, as has been pursued notably bySaviotti andMetcalfe, 1984,op. cit., note 21, Technological paradigms and technological trajectories,Research Policy, 11 (1982) 147–62 andSaviotti 1988,op. cit., note 21 Technological paradigms and technological trajectories,Research Policy, 11 (1982) 147–62.

Theil 1972.

Callon et al. 1983,. See also:Leydesdorff, 1990e,op. cit., note 13. The scientometrics challenge to science studies,EASST Newsletter 9(1990a, No. 1) 7–11.

Nelson, Winter,.

However, the various forms of coupling (structural, operational, loose) have first to be further specified. See also:L. Leydesdorff, “Structure”/“Action” Contingencies and the Model of Parallel Computing, (forthcoming);L. Leydesdorff, The Duality of Structure and the Theory of Autopoiesis, (in preparation).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leydesdorff, L. Irreversibilites in science and technology networks: An empirical and analytical approach. Scientometrics 24, 321–357 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02017914

Received:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02017914