Abstract

In this article, we work with data from the Soul of the Community survey project that was conducted by the Knight Foundation from 2008 to 2010. Overall, 26 communities across the United States with a total of more than 47,800 participants took part in this study. Each year, around 200 different questions were posed to each participant. One key variable is attachment to one’s community. In our article, we provide an assessment via various machine learning algorithms which factors may have an effect on attachment.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Becker RA, Wilks AR, Brownrigg R, Minka TP (2013) Maps: draw geographical maps. R package version 2.3-2. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=maps. Accessed 12 Dec 2018

Boser BE, Guyon IM, Vapnik VN (1992) A training algorithm for optimal margin classifiers. In: Proceedings of the 5th annual workshop on computational learning theory (COLT’92). ACM Press, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, pp 144–152

Breiman L (2001) Random forests. Mach Learn 45(1):5–32

Breiman L, Cutler A (2014) Random forests. http://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~breiman/RandomForests/cc_home.htm. Accessed 21 May 2014

Breiman L, Friedman J, Olshen R, Stone C (1984) Classification and regression trees. Wadsworth and Brooks, Monterey

Cook D (2014) ASA 2009 data expo. Comput Stat 29(1–2):117–119

Cutler A, Breiman L (1994) Archetypal analysis. Technometrics 36(4):338–347

Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D (1998) Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci 85:14,863–14,868

Fernández-Delgado M, Cernadas E, Barro S, Amorim D (2014) Do we need hundreds of classifiers to solve real world classification problems? J Mach Learn Res 15:3133–3181

Fisher RA (1936) The use of multiple measurements in taxonomic problems. Ann Eugen 7(7):179–188

Hofmann H (2013) Soul of the community. http://streaming.stat.iastate.edu/dataexpo/2013/. Accessed 12 Nov 2013

Hofmann H, Wickham H, Cook D (2019) The 2013 data expo of the American Statistical Association. Computational Statistics XX(YY): This issue

Inselberg A (2009) Parallel coordinates: visual multidimensional geometry and its applications. Springer, New York

James G, Witten D, Hastie T, Tibshirani R (2013) An introduction to statistical learning. Springer, New York

Kahle D, Wickham H (2013) ggmap: a package for spatial visualization with Google Maps and OpenStreetMap. R package version 2.3. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggmap. Accessed 12 Dec 2018

Karatzoglou A, Smola A, Hornik K, Zeileis A (2004) kernlab–an S4 package for kernel methods in R. J Stat Softw 11(9):1–20

Knight Foundation (2013) Soul of the community. http://www.soulofthecommunity.org/. Accessed 12 Nov 2013

Knight Foundation (2014) http://www.knightfoundation.org. Accessed 23 May 2014

Knight Foundation (2015) http://www.knightfoundation.org/about/. Accessed 3 Mar 2015

Kuhn M, Wing J, Weston S, Williams A, Keefer C, Engelhardt A (2012) caret: classification and regression training. R package version 5.15-023. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=caret

Liaw A, Wiener M (2002) Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2(3):18–22

Murrell P (2010) The 2006 data expo of the American Statistical Association. Comput Stat 25(4):551–554

Neuwirth E (2011) RColorBrewer: ColorBrewer palettes. R package version 1.0-5. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RColorBrewer. Accessed 24 Mar 2015

Quach A, Symanzik J, Forsgren Velasquez N (2013) Soul of the community: a first attempt to assess attachment to a community. In: 2013 JSM proceedings, American Statistical Association, Alexandria, VA

R Core Team (2013) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, http://www.R-project.org/, ISBN 3-900051-07-0

Rowley E (November, 2011) Is loving where you live the key to a successful community? http://www.soulofthecommunity.org/content/loving-where-you-live-key-successful-community

Schloerke B, Crowley J, Cook D, Hofmann H, Wickham H (2012) GGally: extension to ggplot2. R package version 0.4.2. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=GGally. Accessed 24 Mar 2015

Wegman EJ (1990) Hyperdimensional data analysis using parallel coordinates. J Am Stat Assoc 85(411):664–675

Wickham H (2009) ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer New York, http://had.co.nz/ggplot2/book

Wickham H (2011a) ASA 2009 data expo. J Comput Graph Stat 20(2):281–283

Wickham H (2011b) The split-apply-combine strategy for data analysis. J Stat Softw 40(1):1–29

Wickham H (2012) scales: scale functions for graphics. R package version 0.2.3. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=scales. Accessed 24 Mar 2015

Williams C (November, 2013) Detroit Mayor Dave Bing says bankruptcy was ‘inevitable’ after city hit rock-bottom. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/11/08/dave-bing-detroit-bankruptcy-inevitable-mayor-_n_4239772.html?utm_hp_ref=detroit-bankruptcy

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Adele Cutler for her input on the methodology of this manuscript and for providing access to her archetype software. In addition, we would like to thank the reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. This article was submitted prior to Jürgen Symanzik becoming Editor-in-Chief of Computational Statistics, and was handled by Yuichi Mori, the previous Editor-in-Chief.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

A Appendix

A number of variables and cases were removed prior to our analyses. Variables were removed for the following reasons: (i) Variables with a large number of missing responses (more than 45%) among the cases were excluded. (ii) When variables were provided as 5–level variables and also as aggregated 3–level variables (variables names ending with an r), the aggregated 3–level variables were removed as they provided less nuanced information. (iii) Variables not observed in all 3 years were excluded for comparison purposes. (iv) All index variables (see Table 3) were removed, assuming that the variables that were aggregated into an index variable would show up together if the index variable is an important predictor variable. Including the index variables that are linearly dependent on the variables they were derived from creates issues in some of the models we used. We determined how the index variables were derived by using PCA. (v) Finally, all variables were removed that form the basis for “Community Attachment” (which is one of our main response variables). For (iv) and (v), PCA was conducted. Ultimately, 55 variables were retained for our analysis from the original 179 (2008), 195 (2009), and 229 (2010) variables, respectively.

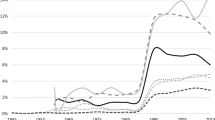

After the removal of variables, cases were removed for the following reasons: (i) Cases with at least one missing value in the remaining variables were removed. (ii) Answers such as “don’t know”, “refuse to answer”, or “did not answer the question” in the survey were replaced as missing and then were handled according to (i). Figure 12 shows the effect of data cleaning for the sample sizes in each community in each year. Although steps (i) and (ii) sound rigorous, in most communities/years, only a few cases had to be deleted. Notice that communities with considerable decreases in sample size after data cleaning were mostly urban communities (such as Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Miami, Florida, and San Jose, California, in 2008 and Charlotte, North Carolina, Akron, Ohio, and Detroit, Michigan, in 2009). An explanation of why we see these dramatic changes in urban communities following data cleaning would be interesting, but has not been investigated here.

Figure 13 provides a graphical representation of the variables and cases that were removed from further analysis. Overall, the largest number of cases were removed from the 2010 data set, but the original sample size that year was approximately 50% larger than the sample sizes in 2008 and 2009.

B Appendix

“Appendix B” summarizes the predictor variables in Table 4 and lists additional variables related to the index variables in Table 5. The variables in bold in Table 4 are the variables that are found to be the three most important predictor variables in predicting attachment status. The table also lists some of the variables that make up the index variables in Table 3. Table 5 lists the remaining variables and descriptions used to make up the index variables in Table 3.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Quach, A., Symanzik, J. & Forsgren, N. Soul of the community: an attempt to assess attachment to a community. Comput Stat 34, 1565–1589 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00180-019-00866-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00180-019-00866-2