Notes

Further discussion of subject-matter is to be found in [7].

I also make use of a variety of impossible states in developing a truthmaker semantics for intuitionistic logic in [4].

We should perhaps also allow any proposition P to be partly about the null subject-matter ⎕.

Closure under negation also requires that we take the falsifiers of a proposition into account in ascertaining its subject-matter.

Suppose that R did not contain p, for example. Then the truth of Q ∧ R could not turn on the truth-value of p when r and q were true.

References

Angell, R. B (1977). Three Systems of First Degree Entailment. Journal of Symbolic Logic, 47, 147.

Correia, F (2010). Grounding and Truth-Functions. Logique et Analyse, 53, 251–79.

Fine, K. (2012). The Pure Logic of Ground. The Review of Symbolic Logic, 5 (1), 1–25.

Fine, K (2014). Truthmaker Semantics for Intuitionistic Logic. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 43.2, 549–77. reprinted in Philosophers’ Annual for 2014.

Fine, K. (2015). Angellic Content. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 1–25. doi:10.1007/s10992-015-9371-9.

Fine, K. (2016). Constructing the Impossible. to appear in a collection of papers for Dorothy Edgington.

Fine, K. (2017). Yablo on Subject-Matter: to appear in Philosophical Studies.

Hudson, J.L. (1975). Logical Subtraction. Analysis, 35.4, 130–5.

Humberstone, L. (2000). Parts and Partitions. Theoria, 66, 41–82.

Jaeger, R.A. (1973). Action and Subtraction. Philosophical Review LXXXII, 2, 320–9.

Jaeger, R.A. (1976). Logical Subtraction and the Analysis of Action. Analysis, 36.2, 141–6.

Yablo, S. (2014). Aboutness. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix: Formal Appendix

ᅟ

Preliminaries

The technical appendix from part I is presupposed; and results from that appendix are prefixed with a ‘I’, as with ‘lemma I.1’.

We define a product space in the usual way. Given two spaces S = (\(S, \sqsubseteq \)) and S ′= (\(S^{\prime }, \sqsubseteq ^{\prime }\)), their product space S ×S ′ will be (\(S \times S^{\prime }, \sqsubseteq ^{*}\)), where:

(s,t) \(\sqsubseteq ^{*}\) (s ′ ,t ′) iff \(s \sqsubseteq s^{\prime }\) and \(t \sqsubseteq t^{\prime }\).

When S and S’ are modalized spaces (\(S, S^{\mathrm {\Diamond }}, \sqsubseteq \)) and (\(S^{\prime }, S^{\prime \mathrm {\Diamond }}, \sqsubseteq ^{\prime }\)), we may take their product S × S ′ to be (S × S ′, (S × S ′)♢, \(\sqsubseteq \) *), with \(\sqsubseteq \) * as before and with (S × S ′)♢ = (S ♢ × S ′♢) (although more restrictive definitions of (S × S ′)♢ might also be given).

We readily show:

Lemma 1

If S and S ′ are modalized or unmodalized state spaces then so is S × S ′, with (s1, t1) ⊔* (s2, t2) ⊔∗ ... = (s1 ⊔ s 2 ⊔ ..., t1 ⊔ t 2 ⊔ ...} for s1, s 2, ... ∈ S and t1, t 2, ... ∈ T.

We say that r is a remainder of t given \(s \sqsubseteq t\) if (i) r ⊔ s=t and (ii) r and s are disjoint; and the space S is said to be remaindered if it is distributive and if for any states s, t ∈ S with \(s \sqsubseteq t\), there is a remainder of t given s. In a remaindered space, the remainder r of t given \(s \sqsubseteq t\) is unique; and we denote it by t−s. We may extend the notion of remainder to arbitrary t and s by taking t−s=t−(t⊓s).

We state without proof the following facts about remainders within a remaindered space, to which implicit appeal will be made in the proofs to follow:

-

(i)

(t−u) ⊔ u=t for \(u \sqsubseteq t\)

-

(ii)

t−u and u are disjoint

-

(iii)

if \(s \sqsubseteq t\) and s is disjoint from \(u \sqsubseteq t\) then s\(\sqsubseteq t-u\)

-

(iv)

if \(t \sqsubseteq t^{\prime }\) and s ′ \(\sqsubseteq s\) then \(t-s \sqsubseteq t^{\prime } - s^{\prime }\)

-

(v)

(s ⊔ t)−u= (s−u) ⊔ (t−u)

Common Conjunctive Part

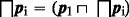

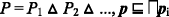

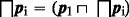

Given regular verifiable propositions P

1, P

2, ..., we take their mereological intersection (common conjunctive part) P = P

1 ∇ P

2

∇ ... to be {

q

:

q = p ⊓  for some p ∈ P

1

∪

P

2

∪ ...} when there are some

P

1,P

2

, ... and to be

F

▪

= { ▪} otherwise. For each i, p

i

is the subject-matter of P

i

and so

for some p ∈ P

1

∪

P

2

∪ ...} when there are some

P

1,P

2

, ... and to be

F

▪

= { ▪} otherwise. For each i, p

i

is the subject-matter of P

i

and so  is the common subject matter of P

1,P

2

, .... Thus

P

1 ∇ P

2∇ ... is obtained by restricting the verifiers in P

1, P

2, ... to their common subject matter.

is the common subject matter of P

1,P

2

, .... Thus

P

1 ∇ P

2∇ ... is obtained by restricting the verifiers in P

1, P

2, ... to their common subject matter.

We have the following external characterization of common conjunctive part:

Theorem 2

Suppose that P 1 , P 2 , ... are regular verifiable propositions and that P = P1 ∇ P 2 ∇ .... Then:

-

(i)

(i)

-

(ii)

P is the greatest regular verifiable proposition to be contained in each of P1, P 2, ....

-

(iii)

P is the conjunction of all the regular verifiable propositions to be contained in each of P1, P 2, ....

Proof

-

(i)

When there are no P 1, P 2, ...,P = F ▪ and

. So suppose there are some P

1, P

2, ... . Then

. So suppose there are some P

1, P

2, ... . Then  =

=  ..., given that each p

i

is the maximal member of P

i

. But

..., given that each p

i

is the maximal member of P

i

. But  .

. -

(ii)

The result follows from lemma I.2 when there are no P i , since p = F ▪ is the greatest regular verifiable proposition. So suppose that there are some P i and that p , say, is a member of P 1. Then

and so P is verifiable. We establish the following further facts in completing the demonstration of (ii):

and so P is verifiable. We establish the following further facts in completing the demonstration of (ii):

-

(1)

P is regular. (a)

by (i) and

by (i) and  ∈ P. (b) Suppose q ∈ P and

∈ P. (b) Suppose q ∈ P and  . Then q is of the form

. Then q is of the form  for some p ∈ P

i

. Since

for some p ∈ P

i

. Since  and P

i

is a regular proposition, p ⊔q

′

∈

P

i

. But then

and P

i

is a regular proposition, p ⊔q

′

∈

P

i

. But then

.

. -

(2)

P is contained in each of P 1,P 2, ... . Take p ∈ P . Then p is of the form

withP

′

∈

P

i

for some i. But then

withP

′

∈

P

i

for some i. But then  p

\(_{\mathrm {i}} \sqsubseteq \)

p

i

∈

P

i

. Now suppose p ∈ P

i

. Then

p

\(_{\mathrm {i}} \sqsubseteq \)

p

i

∈

P

i

. Now suppose p ∈ P

i

. Then  .

. -

(3)

P is the greatest proposition to be contained in each of P 1,P 2 , .... Take a proposition R that is contained in each P i . We wish to show R ≤ P. Suppose first that r ∈ R. Since R ≤ P i for each i, \(r \sqsubseteq \) p i for each i, and so

. Now suppose p ∈ P . Then p is of the form

. Now suppose p ∈ P . Then p is of the form  with P

′

∈

P

i

for some i. So P

′

\(\sqsupseteq r\) for some r ∈ R given that R ≤ P

i

. Also each p

\(_{\mathrm {i}} \sqsupseteq r\), given that R is contained in each P

i

,

with P

′

∈

P

i

for some i. So P

′

\(\sqsupseteq r\) for some r ∈ R given that R ≤ P

i

. Also each p

\(_{\mathrm {i}} \sqsupseteq r\), given that R is contained in each P

i

,  . But then

. But then  .

.

-

(1)

-

(iii)

From (ii) by theorem I.12.

Note that, in the special case of two propositions P and Q , we may take their common content \(P \triangledown Q\) to be {p ⊓ q : p ∈ P} ∪ {q ⊓ p : q ∈ Q } . The characterization of the common content of two propositions also simplifies when one of them is definite:

Corollary 3

If P and Q are regular verifiable propositions and one of them is definite, then \(P \triangledown <Emphasis Type="Italic">Q</Emphasis> =\) { p ⊓ q: p ∈ P and q ∈ Q} .

Proof

Without loss of generality, assume Q = {q 0} . Then:

\(P \triangledown <Emphasis Type="Italic">Q</Emphasis> =\) {p ⊓ q : p ∈ P} ∪ {q ⊓ p:q ∈ Q }

= {p ⊓ q 0:p ∈ P} ∪ {q 0 ⊓ p}

= {p ⊓ q : p ∈ P and q ∈ Q } since p ∈ P and Q = {q 0}.

A greatest common part of P and Q may not exist when P and Q are only required to be semi-regular. For let P = {pq, rs} and Q = {pr, qs} (in the canonical space). Then P and Q are both semi-regular propositions, {p, r} and {q, s} are both maximal common parts of P and Q, and yet neither is a part of the other. When we turn, on the other hand, to the regular closures P\(_{\ast }^{\ast }\) and Q \(_{\ast }^{\ast }\) of P and Q, their greatest common part will be {pq, rs, pr, qs} \(_{\ast }^{\ast }\).

The common part of one or more regular propositions is related to their disjunction, with the common part of the propositions being identical to the common part of their disjunction and their common subject-matter:

Lemma 4

Where P

1, P

2, ... are one or more regular verifiable propositions, \(P_{1} \triangledown P_{2} \triangledown \) ... = (\(P_{1} \vee P_{2} \vee ...)\triangledown \)

.

.

Proof

Suppose \(q \in P_{1} \triangledown P_{2}\triangledown ....\) Then q is of the form  for p ∈ P

1

∪

P

2 ∪ .... But

for p ∈ P

1

∪

P

2 ∪ .... But  and so

and so  . Now suppose q

∈ (

\(P_{1} \vee P_{2} \vee ...)\triangledown \)

. Now suppose q

∈ (

\(P_{1} \vee P_{2} \vee ...)\triangledown \)

. Then q is of the form

. Then q is of the form  where, for some i and p

i

∈

P

i

, \(p_{\mathrm {i}} \sqsubseteq p \sqsubseteq \)

p

1 ⊔ p

2 ⊔ .... But q is also identical to

where, for some i and p

i

∈

P

i

, \(p_{\mathrm {i}} \sqsubseteq p \sqsubseteq \)

p

1 ⊔ p

2 ⊔ .... But q is also identical to  , where \(p_{\mathrm {i}} \sqsubseteq \) (p ⊓ p

i

) \(\sqsubseteq \)

p

i

and hence (p ⊓ p

i

) ∈

P

i

; and so \(q \in P_{1} \triangledown P_{2} \triangledown ... .\)

, where \(p_{\mathrm {i}} \sqsubseteq \) (p ⊓ p

i

) \(\sqsubseteq \)

p

i

and hence (p ⊓ p

i

) ∈

P

i

; and so \(q \in P_{1} \triangledown P_{2} \triangledown ... .\)

Common Disjunctive Part

We also have a ‘vertical’ dual to disjunction. Given the propositions P 1,P 2, ..., we let their logical intersection (common disjunctive part) P be \(P_{1}\, \triangledown \, P_{2}\, \triangledown \) ... = P 1 ∩ P 2 ∩ .... Note that there is no guarantee that P will be non-empty when P 1,P 2, ... are non-empty and that there will, in general, be no way to determine the subject-matter of P from the subject matter of P 1,P 2, ... Thus within the canonical space, the subject-matter of {p, q} and {pq} will be the same, viz. pq, while the common subject-matters {p, q, pq} △ {p} = {p} and {pq} △ {p} = ∅ will be different.

Theorem 5

Suppose that P 1, P 2, ... are regular propositions and that P = P 1 △P 2 △ ... . Then:

-

(i) P is the weakest regular proposition to entail each of P 1 , P 2 , ...;

-

(ii) P is the disjunction of all the regular propositions to entail each of P 1, P 2, ....

Proof

-

(i)

This is clearly true if P is empty and so we may suppose P is non-empty. We establish the following facts in turn:

-

(1)

p ∈ P. Each p ∈ P belongs to each P i ; so

belongs to each P

i

, given that the P

i

are regular, and so p ∈ P.

belongs to each P

i

, given that the P

i

are regular, and so p ∈ P. -

(2)

P is convex. Suppose \(p \sqsubseteq q \sqsubseteq r\) with p, r ∈ P. Then p, r belongs to each P i ; so q belongs to each P i , given that the P i are regular; and so q ∈ P.

-

(3)

P is regular. From (1) and (2).

-

(4)

P is the weakest regular proposition to entail each P i . Evident from the definition of P.

-

(1)

-

(ii)

From (i) by theorem I.14.

Common Conjunctive and Disjunctive Part - the Bilateral Case

Given regular verifiable propositions P 1 = ( P 1, \(P^{\prime }_{1}\)), P 2 = (P 2, \(P^{\prime }_{2}\)), ..., we let their mereological intersection (common conjunctive part) P = P \(_{1}\,\triangledown \) P \(_{2}\, \triangledown \) ... be (\(P_{1}\,\triangledown P_{2}\,\triangledown \) ..., \(P_{1}^{\prime }\) △ \(P_{2}^{\prime }\) △ ... ); and given regular falsifiable propositions P 1 = (P 1, \(P^{\prime }_{1}\)), P 2 = ( P 2, \(P^{\prime }_{2}\)), ..., we let their logical intersection (common disjunctive part) P = P 1 △P 2 △ ... be (P 1 △ P 2 △ ..., \(P_{1}^{\prime }\) \(\triangledown \) \(P_{2}^{\prime }\) \(\triangledown \)...). These definitions are in perfect analogy to the definitions of conjunction and disjunction in the bilateral case.

Theorems 2 and 5 may be extended to bilateral propositions in the obvious way. However, there is a peculiar difficulty in the present case. Within a Boolean domain, we can be sure that the conjunction P c of all the regular verifiable propositions to be contained in each of the given verifiable propositions P 1, P 2, ... will exist and that the disjunction P d of all the regular propositions to entail each of P 1, P 2, ... will exist; and we can also be sure that if P 1 \(\triangledown \) P \(_{2}\,\triangledown \) ... belongs to the propositional domain then it will be identical to the conjunction P c and that if P 1 △ P 2 △ ... belongs to the propositional domain then it will be identical to the disjunction P d. But we can have no general assurance either that P 1 \(\triangledown \) P \(_{2}\,\triangledown \) ... or P 1 △ P 2 △ ... will exist in suitably constrained domains or that they will inherit desirable properties of the component propositions P 1, P 2, ..., such as bivalence, should they exist (a case of this sort is discussed in the introduction).

It would be of interest to determine the conditions for the common conjunctive or disjunctive part of given bilateral propositions to be ‘well-behaved’, under different determinations of what it is for a proposition to be well-behaved. Another line of solution is to let the falsifiers of the common conjunctive or disjunctive part ‘fall where they may’. Thus given the verifiable propositions P 1, P 2, ..., we may let their common conjunctive content be ((P 1 ∇ P 2 ∇ ...), ∼ (P 1 ∇ P 2 ∇ ...)), where ∼(P 1 ∇ P 2 ∇ ...) is the exclusionary negation of (P 1 ∇ P 2 ∇ ...) as defined in part I; and similarly for the common disjunctive part. The common conjunctive or disjunctive part is defined, in effect, in terms of the positive content of the given propositions; and the negative content is ignored. But even in this case, it will be necessary to allow there to be trivial propositions distinct from \(T_{\mathrm {\,{\square }\,}}\), since in many cases the common unilateral content will be such a proposition, as with the common conjunctive content {p, \(\square \,\)} of {p, q} and {p}.

Differentiated Content

Differentiated spaces will be helpful in developing the theory of logical remainder and subject-matter.

Given an ordinary (undifferentiated) space S, we take the corresponding differentiated space to be the product space S × S, as previously defined. Intuitively, we think of each state s from S as being differentiated into two parts s 1,s 2, with s = s 1 ⊔ s 2, thereby giving us a differentiated state (s 1,s 2) within S × S.

Given a differentiated state π= (s, t) ∈ S × S, there are three states from S that may be associated with it: the initial state π1=s, the additional state π 2=t, and the total state π 1, 2=s ⊔t. Similarly, given a differentiated content π ⊆ S × S from S × S, there are three associated contents: the initial content π 1 = {π 1:π ∈ π} (= {s ∈ S: for some t ∈ S, (s, t) ∈ π}), theadditional content π 2 = {π 2:π ∈ π} (= {t ∈ S: for some s ∈ S, (s, t) ∈ π}); and the total content π 1, 2= {π 1, 2: π ∈ π} (= {s ⊔ t: (s, t) ∈ π}).

Lemma 6

If π is a regular content in the differentiated space S × S, then π1, π2 and π1, 2 are regular contents in the undifferentiated space S.

Proof

Suppose π is a regular content. The results are evident when π= ∅ and so let us suppose π is non-empty.

-

(1)

π1 is regular. For suppose π 1= {s 1,s 2, ...} . Then for each i, there is a state t i for which (s i ,t i ) ∈ π. (a) (s 1,t 1) ⊔ (s 2,t 2) ⊔ ... = (s 1 ⊔ s 2⊔ ...,t 1 ⊔ t 2 ⊔ ...) ∈ π, given that π is regular; and so \(\bigsqcup \) π 1=s 1 ⊔ s 2 ⊔ ... ∈ π 1. (b) Now suppose \(s \sqsubseteq s^{\prime }\) \(\sqsubseteq s^{\mathrm {+}}\), with s, s + ∈ π 1. Then for some t, t + ∈ S, (s, t), (s +,t +) ∈ π. Since π is regular, (s ⊔s +,t ⊔t +) = (s +,t ⊔t +) ∈ π and, given that (s, t) \(\sqsubseteq \) (s’,t) \(\sqsubseteq \) (s +,t ⊔t + ), ( s ′ , t) ∈ π and hence s ′ ∈ π 1.

-

(2)

π2 is regular. Similar to (1).

-

(3)

π1, 2 is regular. (a) Let π 1= {s 1,s 2, ...} and π 2= {t 1,t 2, ...} . Then \(\bigsqcup \) π 1, 2 =⊔ π 1 ⊔ \(\bigsqcup \) π 2. But \(\bigsqcup \) π = (\(\bigsqcup \) π 1, \(\bigsqcup \) π 2) ∈ π and so \(\bigsqcup \) π 1, 2=\(\bigsqcup \) π 1 ⊔ \(\bigsqcup \) π 2 ∈ π 1, 2. (b) Suppose s ⊔t \(\sqsubseteq u \sqsubseteq s^{\prime }\) ⊔ t ′, with (s, t ), ( s ′ , t ′) ∈ π. Since π is regular, (s ⊔s ′ , t ⊔t ′) ∈ π. So without loss of generality, we may suppose \(s \sqsubseteq s^{\prime }\) and t \(\sqsubseteq t^{\prime }\). But u = u ⊔ ( s ′ ⊔ t ′) = (u ⊔s ′) ⊔ (u ⊔t ′), \(s \sqsubseteq \) (u ⊔s ′ ) \(\sqsubseteq s^{\prime }\) and \(t \sqsubseteq \) (u ⊔t ′ ) \(\sqsubseteq t^{\prime }\); and so (u ⊔s ′ , u ⊔t ′) ∈ π, given that π is regular, from which it follows that u= (u ⊔s ′ ) ⊔ ( u ⊔t ′ ) ∈ π 1, 2.

Coordinated Conjunction

For π a differentiated content and R, Q , P undifferentiated verifiable contents: we say P is the π-conjunction of R and Q - in symbols, R ∧π Q =P - if π1=R, π 2= Q and π 1, 2=P; and we say P is a coordinated conjunction of R and Q- or, with an abuse of notation, R ∧ ∙ Q =P - if R ∧π Q = P for some regular differentiated content π. Note that R ∧π Q is not taken to be defined unless R and Q are verifiable, π1=R and π 2 = Q .

In a coordinated conjunction, the ‘conjuncts’ are coordinated with one another via a differentiated content, with the ‘disjunct’ r in R fused with the disjunct q in Q just in case (r, q) is a state within the coordinating content π. The ordinary conjunction R ∧ Q is the special case of a coordinated conjunction R ∧ π Q in which π= R × Q.

The following results follow straightforwardly from the definitions:

Lemma 7

-

(i) R≤c R∧π Q and Q ≤c R ∧π Q;

-

(ii) π⊆π′ implies \(R \wedge _{\mathrm {\Pi }} <Emphasis Type="Italic">Q</Emphasis> \le _{\mathrm {d}} <Emphasis Type="Italic">R</Emphasis> \wedge _{\mathrm {\Pi ^{\prime }}} Q\) for differentiated contents π⊆π′, and π⊆π′ implies \(R \wedge _{\mathrm {\Pi ^{\prime }}} <Emphasis Type="Italic">Q</Emphasis> \le _{\mathrm {c}} <Emphasis Type="Italic">R</Emphasis> \wedge _{\mathrm {\Pi }} Q\) for regular differentiated contents π⊆π′;

-

(ii) R∧π Q≤ d R ∧ Q and R∧Q ≤ c R∧π Q for regular π.

Coordinated conjunction is preserved under regular closure:

Lemma 8

Suppose R ∧π Q = P. Then \(R^{\ast }_{\ast }\) \(\wedge _{\mathrm {\Pi }^{\ast }} Q^{\ast }_{\ast } = P^{\ast }_{\ast }\).

Proof

It should be clear that  and so \(\Pi ^{*}_{*} = \{(r^{\prime }, q^{\prime }): (r, q) \in \Pi , r \sqsubseteq r^{\prime } \sqsubseteq \textit {\textbf {r}} \text { and } q \sqsubseteq q^{\prime } \sqsubseteq \left .\textit {\textbf {q}}\right )\}\).

and so \(\Pi ^{*}_{*} = \{(r^{\prime }, q^{\prime }): (r, q) \in \Pi , r \sqsubseteq r^{\prime } \sqsubseteq \textit {\textbf {r}} \text { and } q \sqsubseteq q^{\prime } \sqsubseteq \left .\textit {\textbf {q}}\right )\}\).

-

(1)

\(\Pi ^{*}_{* 1}\subseteq R^{*}_{*}\) and \(\Pi ^{*}_{* 2} \subseteq Q^{*}_{*}\). Pf. Suppose (r ′ , q ′ ) \(\in \Pi ^{*}_{*}\) (to show r ′ \(\in R^{*}_{*}\) and q ′ \(\in Q^{*}_{*})\). Then for some (r, q) ∈ π, \(r \sqsubseteq r^{\prime }\) \(\sqsubseteq \) r and \(q \sqsubseteq q^{\prime }\) \(\sqsubseteq \) q. Given that R ∧ π Q = P, r ∈ R, q ∈ Q; r \(\in R^{*}_{*}\) and q ∈ Q \(^{*}_{*}\); and so, given that \(r \sqsubseteq r^{\prime }\) \(\sqsubseteq \) r and \(q \sqsubseteq q^{\prime }\) \(\sqsubseteq \) q, r ′ \(\in R^{*}_{*}\) and q ′ \(\in Q^{*}_{*}\).

-

(2)

\(R^{*}_{*} \subseteq \Pi ^{*}_{* 1}\) and \(Q^{*}_{*}\) \(\subseteq \Pi ^{*}_{* 2}\) .Pf. Suppose r ′ \(\in R^{*}_{*}\) (the case in which q ′ \(\in Q^{*}_{*}\) is similar). Then r \(\sqsubseteq r^{\prime }\) \(\sqsubseteq \) r for some r ∈ R. So (r, q) ∈ π for some q ∈ Q . But then \(r \sqsubseteq r^{\prime }\) \(\sqsubseteq \) r and \(q \sqsubseteq q \sqsubseteq \) q; and so (r ′, \(q) \in \Pi ^{*}_{*}\), from which it follows that \(R^{*}_{*} \subseteq \Pi ^{*}_{* 1}\).

From (1) and (2), we obtain:

-

(3)

\(\Pi ^{*}_{* 1} = R^{*}_{*}\) and \(\Pi ^{*}_{* 2} = Q^{*}_{*}\).

-

(4)

\(\Pi ^{*}_{* 1,2} \subseteq P^{*}_{*}\).Pf. Take (r ′ , q ′ ) \(\in \Pi ^{*}_{*}\), with (r, q) ∈ π, \(r \sqsubseteq r^{\prime }\) \(\sqsubseteq \) r and \(q \sqsubseteq q^{\prime }\) \(\sqsubseteq \) q. Since r ∈ R and q ∈ Q, r ⊔q ∈ \(P^{*}_{*}\) and, since

. But \(r \,\sqcup \, q \sqsubseteq r^{\prime }\)

\(\,\sqcup \, q^{\prime } \sqsubseteq \)

r ⊔ q; and sor

′

\(\,\sqcup \, q^{\prime } \in P^{*}_{*}\).

. But \(r \,\sqcup \, q \sqsubseteq r^{\prime }\)

\(\,\sqcup \, q^{\prime } \sqsubseteq \)

r ⊔ q; and sor

′

\(\,\sqcup \, q^{\prime } \in P^{*}_{*}\). -

(5)

\(P^{*}_{*} \subseteq \Pi ^{*}_{* 1,2}\) .Pf. Suppose P ′ \(\in P^{*}_{*}\). Then for some p ∈ P, \(p \sqsubseteq p^{\prime }\) \(\sqsubseteq \) p = r ⊔ q. But p is of the form r ⊔qfor (r, q ) ∈ π. Now p ′ = p ′ ⊓ (r ⊔ q) = (p ′ ⊓ r) ⊔ (p ′ ⊓ q), \(r \sqsubseteq \) (P ′ ⊓ r) \(\sqsubseteq \) r and \(q \sqsubseteq \) (p ′ ⊓ q) \(\sqsubseteq \) q. So (p ′ ⊓ r, p ′ ⊓ q) \(\in \Pi ^{*}_{*}\) and, consequently, p ′ = ( p ′ ⊓ r) ⊔ (p ′ ⊓ q) \(\in \Pi ^{*}_{* 1,2}\).

From (4) and (5), we obtain:

-

(6)

\(\Pi ^{*}_{* 1,2} = P^{*}_{*}\).

The required result then follows from (3) and (6).

Logical Remainder

We deal with two kinds of remainder - first, those required to be least with respect to the containment and, second, those required to be weakest with respect to entailment.

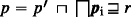

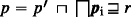

Suppose P and Q are regular verifiable propositions within a remainder space. We then define P−Q to be {p – q : p ∈ P} . Thus P−Q is obtained, so to speak, by subtracting the subject-matter of Q from P.

It should be noted that the value of R = P− Q , for given P, depends only upon the subject-matter q of Q and not on its actual constitution. However, when Q ≤ c P, the identity of P and R will tell us something about the identity of Q. For given p ∈ P, there will be a q ∈ Q for which \(q \sqsubseteq p\). Let \(q_{p } = \bigsqcup \) { q ∈ Q : \(q \sqsubseteq p\)} . Since Q is regular, q p ∈ Q and, clearly, for any q ∈ Q for which \(q \sqsubseteq p\), \(q \sqsubseteq q_{p}\). Thus q p is the maximal member q of Q for which q \(\sqsubseteq p\). But we now see that p – q = p–q p . For p – q =p – (q ⊔ p) by definition. Given q ∈ Q for which \(q \sqsubseteq p\), \(q \sqsubseteq \) (q ⊔ p) \(\sqsubseteq \) q and so (q ⊔ p) is a maximal member q of Q for which \(q \sqsubseteq p\) and hence is identical to q p . Thus for each p ∈ P,q p = (q ⊔ p) ∈ Q and, setting r p = p−q p , P − Q = { r p : p ∈ P}.

Lemma 9

Suppose that P and Q are regular verifiable propositions within a remaindered space. Then:

-

(i) R=P−Q is a regular verifiable proposition with r = p – q, and

-

(ii) P−Q=P – (P ∇ Q).

Proof

-

(i)

Clearly R is verifiable given that P and Q are verifiable. Now p – q \(\sqsubseteq \) p – q and, given that p ∈ P, r = ⊔{p – q : p ∈ P} = p – q.

Now suppose \(r \sqsubseteq r^{\prime }\) \(\sqsubseteq \) p – q, with r ∈ R (to show r ′ ∈ R). Then r is of the form p – q for p ∈ P. Let p ′ = r ′ ⊔ p. Then p ′ ∈ P, since r ′ \(\sqsubseteq \) p and so \(p \sqsubseteq p^{\prime }\) = r ′ \(\,\sqcup \, p \sqsubseteq \) p. Hence p ′ − q ∈ R. But p ′ − q = (r ′ ⊔ p) −q = (r ′−q) ⊔ (p−q) = r ′ ⊔ r = r ′.

-

(ii)

P−Q = {p − q : p ∈ P}= {p – (p ⊔ q): p ∈ P} = P – (P ∇ Q) since \(\bigsqcup (P \nabla Q) =\) p ⊔ q by theorem 2.

Given regular verifiable propositions P and Q , we say that R is a remainder of P from Q if P is a coordinated conjunction of R and Q. Say that R is strictly disjoint from Q if r ⊔ q = ⎕, i.e. if they have no common subject-matter (apart from ⎕), and say that R is a strict remainder of P from Q if R is a remainder of P from Q that is strictly disjoint from Q .

We tie together the internal and external characterizations of remainder:

Theorem 10

Suppose P and Q are regular propositions within a remaindered space with Q ≤ P and r = p –q. Then:

-

(i) There exists a strict remainder of P from Q iff for each q ∈ Q, q ⊔ r ∈ P;

-

(ii) If there exists a strict remainder of P from Q then (a) it is identical to s a strict remainder of P − Q, (b) it is contained in every other remainder of P from Q, and (c) it contains every part R of P strictly disjoint from Q and hence is the conjunction of all such parts.

Proof

-

(i)

First suppose R is a strict remainder of P from Q ; and take any q ∈ Q . Then for some r ∈ R, q ⊔ r ∈ P. Since R ≤ P by lemma 7(i), \(r \sqsubseteq \) p and, since R is a strict remainder, r overlaps no q ∈ Q and hence does not overlap q. But then \(r \sqsubseteq \) r = p – q \(\sqsubseteq \) p and so q ⊔ r \(\sqsubseteq q\) ⊔ r \(\sqsubseteq \) p and q ⊔ r ∈ P.

Now suppose q ⊔ r ∈ P for each q ∈ Q . Let π = {(q p , r p ): p ∈ P} ∪ {(q, r): q ∈ Q } . Then it is evident that π1= Q . Also, π 1, 2 ⊆ P, given that q p ⊔ r p = p ∈ P and that q ⊔ r ∈ P for each q ∈ Q, and \(P \sqsubseteq \Pi _{\mathrm {1,2}}\) given that, for each p ∈ P, q p ⊔ r p = p. Moreover, R = π2 is strictly disjoint from Q and so R is a strict remainder of P from Q.

Note that π2, with π defined above, is identical to P−Q; and so we have also established:

-

(1)

if there exists a strict remainder of P given Q then P−Q is such a remainder.(ii)(a) & (b). This will follow from the following additional facts:

-

(2)

If R is a remainder of P given Q then R ≥ P−Q.

Pf. Suppose R is a remainder of P given Q. For one direction, take r ∈ R. Then for some q ∈ Q and p ∈ P, r ⊔q = p. But \(q \sqsubseteq q_{p}\) ; and so, \(r \sqsupseteq p-q \sqsupseteq p-q_{p} = r_{p} \in P-Q\). For the other direction, we note that, by lemma 9(i), p – qis the maximal element of P−Q; and so we need to show that, for some r ∈ R, p – q \(\sqsubseteq r\). Since R is a remainder, there is a r ∈ R and a q ∈ Q for which r ⊔ q = p. Given \(q \sqsubseteq \) q \(\sqsubseteq \) p, r ⊔ q = p; and so p – q \(\sqsubseteq r\).

-

(3)

If R is a strict remainder of P given Q then R≤P−Q.

Pf. Suppose R is a strict remainder of P given Q . For one direction, take r ∈ R. Then \(r \sqsubseteq \) p and, since R is strictly disjoint from Q, r is disjoint from q; and so \(r \sqsubseteq \) p – q and p – q ∈ P−Q by lemma 9(i). For the other direction, take r ∈ P−Q. Then r is of the form r p for p ∈ P. Since R is a remainder, there is a q ∈ Q and a r ′ ∈ R for which r ′ ⊔ q=p. If r ′ \(\sqsubseteq r\) we are done. So suppose not r ′ \(\sqsubseteq r\). Then some non-null r ′′ \(\sqsubseteq r^{\prime }\) is disjoint from r = r p =p−q p and, since r ′′ \(\sqsubseteq r^{\prime }\) \(\sqsubseteq p\), r ′′ overlapsq p , contrary to the supposition that R is a strict remainder.

-

(1)

-

(ii)

(c) Take a part R of P strictly disjoint from Q. Suppose first that r ∈ R. Since R≤P, \(r \sqsubseteq \) p. But r is disjoint from q and so \(r \sqsubseteq \) p – q ∈ P−Q. Now take p – q ∈ P−Q for p ∈ P. Since R≤P, r \(\sqsubseteq p\) for some r ∈ R. But r is disjoint from q and so \(r \sqsubseteq p\) – q.

Some notes. (1) Pwill be a coordinated conjunction of P−Q and Q but not, in general, a straight conjunction. In order for P to be a straight conjunction it should be required, not merely that q ⊔ r ∈ P for each q ∈ Q, but also that q ⊔ r p ∈ P for each p ∈ P and q ∈ Q. (2) The condition under (i) is equivalent to: for each q ∈ Q, there is an \(r \sqsubseteq \) r for which q ⊔ r ∈ P. For \(q \,\sqcup \, r \sqsubseteq q \,\sqcup \, \) r \(\sqsubseteq \) p and so, by Convexity, q ⊔ r ∈ P if q ⊔ r ∈ P. (3) The condition under (i) may fail. A simple example is with P= {pq} (corresponding to the conjunction p ∧ q) and Q= {p, q} (corresponding to the disjunction p ∨ q) within the canonical space. Q is then a part of P but p – q is the null state and so there is no state contained in p – q that can fuse with either p or q to give back pq.

Jaeger [10] has considered the question of when (to state it in our terms) R∧Q=R ′ ∧Q implies R = R′; and Humberstone ([9], p. 62 et seq.) has considered the related question of when (R∧Q)−Q=R. From the above result, we see:

Corollary 11

-

(i) (R∧Q)−Q=R given that r is disjoint from q;

-

(ii) R∧Q=R′ ∧ Q implies R=R′, given that r and r ′ are both disjoint from q.

Proof

-

(i) Suppose P = (R ∧ Q) with r disjoint from q. Then R is a strict remainder of P from Q; and so, by (ii)(a) of the theorem, R= (R ∧ Q)−Q

-

(ii) Suppose that R ∧ Q = R ′ ∧ Q with r and r ′ both disjoint from q. Then (R ∧ Q) − Q = R and (R ′ ∧ Q) − Q = R ′ by (i) above; and so R = R ′.

In the special case in which the subtracted proposition is determinate, the remainder has an especially simple form:

Corollary 12

Suppose that P is a regular proposition { p1, p2, ...} and that Q ≤P is a determinate proposition { q} within a remaindered space. Then (P−Q)= { p 1 −q, p 2 −q, ...} and P= (P−Q)∧Q.

Proof

Given that Q ≤ P and that P is regular, q ⊔ (p – q) = q ⊔ (p –q) = p ∈ P and so, by (i) and (ii)(a) of theorem 10, P−Q is a strict remainder. But given that Q is the determinate proposition {q}, (P−Q)= {p 1 − q, p 2−q, ...} and the only coordinated conjunction of Q and P−Q is (P−Q) ∧ Q.

Let us briefly discuss the corresponding notion of disjunctive remainder. With conjunctive remainder we remove a conjunct and thereby obtain a lesser proposition, while with disjunctive remainder we remove a disjunct and thereby obtain a stronger proposition. Given propositions P and Q, we may take P− d Q to be {p ∈ P:p disjoint from q} (and we might now write P− c Q in place of P−Q to bring out the contrast with P –\(_{\mathrm {d}}\, Q)\).R = P− d Q will be a regular proposition when P and Q are regular but with r = p – q. In place of the notion of coordinated conjunction, we have the notion of expanded disjunction, where the expanded disjunction of P and Q may contain states of the form p ′ ⊔ q ′ for p ′ \(\sqsubseteq \) some p in P and q ′ \(\sqsubseteq \) some q in Q in addition to the members of P and of Q. When it comes to the bilateral case, we might, as before, define P – c Q, where P = (P, P ′) and Q = (Q, Q ′), to be (P− c Q, ∼(P− c Q)) but we might also take it to be (P− c Q, P ′ – d Q ′), though without any assurance that the resulting proposition will be ‘well-behaved’.

We finally turn to the topic of weak conjunctive remainder, for which the strict disjointness condition is relaxed. Given propositions P and Q with Q ≤ P, let P / Q = {r: for some q ∈ Q, r ⊔ q ∈ P} . (When not Q ≤ P, we may identify P / Q with P ⊔ (P ∇ Q)). Say that two propositions P and Q are disjoint (as opposed to strictly disjoint) if they have no non-trivial proposition as a common conjunctive part.

Theorem 13

For regular verifiable propositions P and Q with Q≤P, R = P / Q is the weakest remainder of P from Q and it is a regular proposition for which r = p and which, within a remaindered space, is disjoint from Q.

Proof

We suppose P and Q are regular verifiable propositions with Q ≤ P and that R = P ⊔Q.

-

(1)

R is a regular verifiable proposition.Pf. Since P is verifiable, it contains a member p ∈ P. Since Q ≤ P, q ⊔ p for some q ∈ Q. But then q ⊔p = p ∈ P; and so q ∈ R and R is verifiable.Further,

. For, given any r

i

∈

R, there is a q

i

∈

Q for which r

i

⊔

q

i

∈

P. But \(\bigsqcup \)

r

i

⊔

\(\bigsqcup \)

q

i

=\(\bigsqcup \) (r

i

⊔

q

i

);

\(\bigsqcup (r_{\mathrm {i}} \,\sqcup \, q_{\mathrm {i}}) \in P\) since P is regular and \(\bigsqcup \)

q

i

∈

Q since Q is regular; and so r = \(\bigsqcup \)

r

i

∈ R.

. For, given any r

i

∈

R, there is a q

i

∈

Q for which r

i

⊔

q

i

∈

P. But \(\bigsqcup \)

r

i

⊔

\(\bigsqcup \)

q

i

=\(\bigsqcup \) (r

i

⊔

q

i

);

\(\bigsqcup (r_{\mathrm {i}} \,\sqcup \, q_{\mathrm {i}}) \in P\) since P is regular and \(\bigsqcup \)

q

i

∈

Q since Q is regular; and so r = \(\bigsqcup \)

r

i

∈ R.(b) Suppose \(r \sqsubseteq r^{\prime }\) \(\sqsubseteq r^{\mathrm {+}}\), with r, r + ∈ R. Then for some q, q + ∈ Q, r ⊔q, r + ⊔ q + ∈ P. But r ⊔q \(\sqsubseteq r^{\prime }\) \(\,\sqcup \, \,q \sqsubseteq \) p. By P regular, r ′ ⊔ q ∈ P; and sor ′ ∈ R.

-

(2)

R is a remainder of P fromQ.

Pf. Let π= {(r, q):q ∈ Q, r ⊔q ∈ P} . Then clearly π1=R and π 2=Q since, for any q ∈ Q, there is a p ∈ P for which \(q \sqsubseteq p\) and so for which q ⊔ p ∈ P. Moreover, R ∧π Q = P. For clearly, R ∧π Q ⊆ P. Now suppose p ∈ P. Then \(p \sqsupseteq q\) for some q ∈ Q and so p = p ⊔q ∈ R ∧π Q. Hence P ⊆ R ∧π Q.

-

(3)

R is the weakest remainder.

Pf. Suppose that r ′ is a remainder. So r ′ ∧π Q = P for some differentiated content π. Take any member r of r ′. Then r ⊔ q ∈ P for some q ∈ P and so r ∈ P ⊔ Q.

-

(4)

r = p.

Pf. p ⊔ q = p with q ∈ Q. So p ∈ R and p \(\sqsubseteq \) r. Also, for each r ∈ R, \(r \sqsubseteq \) p and so r \(\sqsubseteq \) p.

-

(5)

R is disjoint from Q in a remaindered space.

Pf. p – q ∈ R since (p – q) ⊔ q = p. Suppose now that Q and R have in common a non-trivial part T. Then p – q \(\sqsupseteq t \) for some non-null state t ∈ T and also \(t \sqsubseteq q\) \(\sqsubseteq \) q for some q ∈ Q. But then t is a common non-null part of q and p – q, which is impossible.

The contrast between the two forms of remainder may be brought out by considering the case in which P is subtracted from P. As is readily verified, P−P is the completely trivial proposition \(T_{\square } = \{\square \}\) while P / P is the trivial proposition { p:p \(\sqsubseteq \) p} . More generally:

Corollary 14

Suppose that P−Q exists and that Q≤P. Then P / Q= [ P−Q, p].

Proof

Take any r ∈ P ⊔Q. Then for some r ′ ∈ P−Q, r ′ \(\sqsubseteq r \) since P− Q ≤ P / Q by (ii)(b) of theorem 10. But r \(\sqsubseteq \) p. Hence r ′ \(\sqsubseteq r \sqsubseteq \) p; and so r ∈ [P−Q, p]. Take now r ∈ [P−Q, p]. Then for some r ′ ∈ P−Q, r ′ \(\sqsubseteq r\sqsubseteq \) p. But r ′ ⊔ q ∈ P for some q ∈ Q; and so r ⊔q ∈ P and r ∈ P ⊔Q.

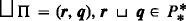

Subject-Matter

Recall that we take the subject-matter p of a proposition P to be \(\bigsqcup \) P and, when P is a regular verifiable proposition, p ∈ P and is the maximal verifier of P.

Let us summarize the previous results on subject-matter:

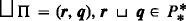

Theorem 15

Let P 1, P2, ... be regular verifiable propositions:

-

(i) When P=P 1 ∧P 2 ∧ ..., p \(= \bigsqcup \) p i

-

(ii) When

-

(iii) When

-

(iv) When

-

(v) When R=P−Q exists, r = p–q

-

(vi) When R=P / Q, r = p.

In other words, the subject-matter of a conjunction or a disjunction is the sum of the subject-matter of the conjuncts or disjuncts, the subject matter of the common part of some propositions is the common part of the their subject-matters; the subject-matter of the common disjunctive part of some propositions is a part of their common subject matter; the subject-matter of the least remainder is the result of subtracting the subject matter of the subtracted proposition from the given proposition; and the subject-matter of the weakest remainder is the same as the subject-matter of the given proposition.

Given a bilateral proposition P = (P, P ′), there will, of course, be the positive subject-matter p and the negative subject-matter (or anti-matter) p ′. But we may also associate with P the comprehensive subject-matter p ± = p ⊔ p ′ and the differentiated subject-matter p +/− = (p, p ′). Given the regular verifiable propositions P 1 = (P 1, \(P_{1}^{\prime }\)), P 2 = (P2, \(P_{2}^{\prime }\)), ..., the comprehensive subject matter p ± = p ⊔ p ′ of P = P 1 ∧ P 2∧ ... = (P 1 ∧P 2 ∧ ..., \(P_{1}^{\prime } \vee P_{2}^{\prime } \vee ...\)) will be the fusion of the comprehensive subject-matters p 1± = p 1 ⊔ p \(_{1}^{\prime }\), p 2± = p 2 ⊔ p \(_{2}^{\prime }\), ... of P 1, P 2, ..., while the differentiated subject-matter p +/− = (p, p ′) of P will be fusion of the differentiated subject-matters p 1+/− = (p 1, p \(_{1}^{\prime }\)), p 2+/− = (p 2, p \(_{2}^{\prime }\)), ... of P 1, P 2, .... The comprehensive subject-matter of ¬P will be the same as the comprehensive subject-matter of P, while the differentiated subject-matter (p ′, p) of ¬P will be the ‘reverse’ of the differentiated subject-matter (p, p ′) of P.

We may restrict a unilateral proposition P to some subject-matter s \(\sqsubseteq \) p. We take the restriction P s of P to s to be {p ⊓ s : p ∈ P}, which we may also denote by P ⊓ s. Thus P s is the common content P ∇ {s} of the proposition P and the associated subject-matter content {s}. So, for example, within the canonical space when P = {pq, pr} and s = qr, P s = {q, r}.

We may also expand a proposition P to some subject-matter s \(\sqsupseteq \) p. We take the expansion P s of P to s to be {P ′: for some p ∈ P, \(p \sqsubseteq p^{\prime }\) \(\sqsubseteq \) s}. Thus when P = {p, q} and s = pqr, P s = {p, q, pq, pr, qr, pqr}.

In general, we may have some subject-matter s for which neither s \(\sqsubseteq \) p nor p \(\sqsubseteq \) s. In this case, we would like to restrict by s ⊓ p and expand by s. We therefore take P s - the conformation of P to s - to be [P ⊓ s, s]. Thus when P = {pq, pr} and s = qrs, P s = {q, r, qr, qs, rq, rs, qrs} .

Lemma 16

Suppose P is a regular verifiable proposition and s some subject-matter. Then:

-

(i) P s is a regular verifiable proposition;

-

(ii) p s = s;

-

(iii) P s=P ⊓ s and P s ≤ P when s \(\sqsubseteq \) p

-

(iv) P s=[ P, s] and P ≤ P s when p \(\sqsubseteq \) s

-

(v) P ss = P s

-

Ps≥Pt iff s \(\sqsupseteq \) t

-

(vi) P s = (Ps⊓p)s = (Ps⊔p)s

Proof

-

(i)

Since P is verifiable, it contains a verifier p. But then p ⊓ s \(\sqsubseteq p \,\sqcap \, \) s \(\sqsubseteq \) s; and so p ⊓ s ∈ P s and P s is verifiable. Moreover, since P s is of the form [P ⊓ s, s], it is automatically regular.

-

(ii)

Evident from the definition of p s.

-

(iii)

P s = [P ⊓ s, s]. So clearly, P ⊓ s ⊆ P s. For the other direction, suppose q ∈ P s. Then for some p ∈ P, p ⊓ s \(\sqsubseteq q \sqsubseteq \) s. Since s \(\sqsubseteq \) p, \(q \sqsubseteq \) p and so p ⊔q ∈ P. But (p ⊔q) ⊓ s = (p ⊓ s) ⊔ (q ⊓ s) = (p ⊓ s) ⊔ q = q and so q ∈ P ⊓ s. Given P ⊓ s ⊆ P s and P s ⊆ P ⊓ s, it follows that P s = P ⊓ s. Moreover, it is evident that P s = P ⊓ s ≤ P.

-

(iv)

P s= [P ⊓ s, s]. But given p \(\sqsubseteq \) s, P ⊓ s = P and so [P ⊓ s, s] = [P, s]. Moreover, it is evident that P ≤ [P, s] = P s.

-

(v)

By (ii), p s = s. So it suffices to show that P s = P when p = s. But in this case, it follows by (iv) that P s = [P, s] = [P, p] = P.

-

(vi)

Suppose P s ≥ P t. Then p \(^{\mathbf {s}} \sqsupseteq \) p t. But by (ii), p s = s and p t = t; and so s \(\sqsupseteq \) t. Now suppose s \(\sqsupseteq \) t. Take q ∈ P s. Then for some p ∈ P, p ⊓ s \(\sqsubseteq q \sqsubseteq \) s. Since s \(\sqsupseteq \) t, p ⊔ s \(\sqsupseteq p\) ⊔ t; and so \(q \sqsupseteq p \,\sqcup \, \) t ∈ P t. For the remaining clause in the definition of ≥, we need to show p \(^{\mathbf {s}} \sqsupseteq \) p t. But this follows from the fact that p s = s, p t = t, and s \(\sqsupseteq \) t.

-

(vii)

P s = [P ⊓ s, s] = [P ⊓ s ⊓ p, s] = [[P ⊓ s ⊓ p, s ⊓ p ], s] = (P s⊓p)s. Also, (P s⊔p) s = [[P ⊓ (s ⊔ p), (s ⊔ p)], s] = [[P, s ⊔ p], s] = {q ⊓ s: \(p \sqsubseteq \) \(q \sqsubseteq \) s ⊔ p for some p ∈ P} = {r:p ⊓ s \(\sqsubseteq \) \(r \sqsubseteq \) s for somep ∈ P} (i.e.P s) since if r = q ⊓ s for \(p \sqsubseteq \) \(q \sqsubseteq \) s ⊔ p for some p ∈ P then p ⊓ s \(\sqsubseteq r \sqsubseteq \) s and if p ⊓ s \(\sqsubseteq r \sqsubseteq \) s for some p ∈ P then, setting \(q = r \,\sqcup \, p, p \sqsubseteq q \sqsubseteq \) s ⊔ p and q ⊓ s = (r ⊔ p) ⊓ s = (r ⊓ s) ⊔ (p ⊓ s) = r ⊔ (p ⊓ s) = r.

The last result ((vii)) says that the conformation of a proposition to some subject-matter can be seen both as the product of a successive restriction and expansion or as the product of a successive expansion and a restriction.

In the bilateral case, we might define the restriction of P s = (P, P ′) to s, for p \(\sqsubseteq \) s and p ′ \(\sqsubseteq \) s, to be (Ps, P*), where P* = {q ∈ P ′: \(q \sqsubseteq \) s} . For suitable choices of P and s, it might then be shown that P s is well-behaved when P is well-behaved.

In a remaindered space, we can define, for any given subject-matter s, its anti-matter (▪-s), which we designate as \(\overline {\boldsymbol {s}}\). Just as we may restrict the content P to s ⊓ p, we may also restrict it to \(\boldsymbol {\overline {s}} \,\sqcap \, \) p. Thus P s⊓p = {s ⊓ p : p ∈ P} and \(P^{\mathrm {\overline {s}\,\sqcap \, \mathbf {p}}} =\) { \(\boldsymbol {\overline {s}} \,\sqcap \, p\) :p ∈ P}. It is helpful to coordinate the respective contents P s⊓p and \(P^{\mathrm {\overline {s}\,\sqcap \, \mathbf {p}}}\). To this end, we define the differentiated restricted content \(P^{\mathbf {s}, \overline {\textbf {{s}}}}\) to be {(s ⊓ p, \(\overline {\boldsymbol {s}} \,\sqcap \, p\)): p ∈ P} ; and, more generally, P s,t= {(s ⊓ p, t ⊓ p):p ∈ P}.

Lemma 17

Suppose that P is a regular verifiable proposition in a remaindered space and that \(\Pi = P^{\mathbf {s}, \overline {\mathbf {s}}}\). Then π is a regular differentiated content for which \(P^{\mathbf {s}} \wedge _{\mathrm {\Pi }} P^{\overline {s}}= P\).

Proof

P contains the maximal verifier p and so π contains the maximal verifier (s ⊓ p, \(\overline {s} \,\sqcap \,\) p). Now suppose (s ⊓ p, \(\overline {s} \,\sqcap \, p\)) \(\sqsubseteq \pi \sqsubseteq \) (s ⊓ p, \(\overline {s} \,\sqcap \,\) p) for p ∈ P (to show π ∈ π). Then π is of the form (π 1,π 2) with s \(\,\sqcap \, p \sqsubseteq \pi _{1}\) \(\sqsubseteq \) s ⊓ p and \(\overline {s} \,\sqcap \, p \sqsubseteq \pi _{2} \sqsubseteq \) \(\overline {s} \,\sqcap \,\) p. Let p * = π 1 ⊔ π 2. Since s \(\,\sqcap \, p \sqsubseteq \pi _{1}\) and \(\overline {s} \,\sqcap \, p \sqsubseteq \pi _{2}\),p = (s \(\,\sqcup \, \overline {s}\)) ⊓ p= (s ⊓ p) ⊔ (\(\overline {s} \,\sqcap \, p\)) \(\sqsubseteq p\) *. Since \(\pi _{1} \sqsubseteq \) s ⊓ p and \(\pi _{2} \sqsubseteq \overline {s} \,\sqcap \, \) p, π 1 ⊔ π 2 \(\sqsubseteq \) (s ⊓ p) ⊔ (\( \overline {s}\,\sqcap \, \) p) = p. Hence \(p \sqsubseteq p\) * \(\sqsubseteq \) p and p * ∈ P. But s ⊓ p * = s ⊓ (π 1 ⊔ π 2) = (s ⊓π 1) ⊔ (s ⊓ π 2) = π 1, given that π 1 \(\sqsubseteq \) s and \(\pi _{2} \sqsubseteq \overline {s}\); and similarly (\(\overline {s} \,\sqcap \, p\) *) =π 2. Hence π= (π 1,π 2) = (s ⊓ p ∗, \(\overline {s} \,\sqcap \, p^{\ast }\)) ∈ π.

It should be clear that π1=P s and that π 2=\(P^{\boldsymbol {\overline {s}}}\). Moreover, π 1, 2 = {(s ⊓ p) ⊔ (\( \boldsymbol {\overline {s}} \,\sqcap \, p\)): p ∈ P} = {(s \(\,\sqcup \, \boldsymbol {\overline {s}} \,)\,\sqcap \,p\): p ∈ P} = P.

Note that, since P s is strictly disjoint from \(P^{\boldsymbol {\overline {s}}}\), it follows that \(P^{\boldsymbol {\overline {s}}} = P\) –P s, just as one might have thought.

Various other notions of aboutness might also be considered. Let us focus on the notion of partial aboutness. Given the subject-matter s and the proposition P, P is said to be partly about s if p and s overlap. We have the following partial compositionality results for partial aboutness:

Lemma 18

For regular verifiable propositions P and Q, the following are equivalent:

-

(i) P∧Q is partly about s;

-

(ii) P∨Q is partly about s;

-

(ii) P is partly about s or Q is partly about s.

Proof

Suppose R = P ∧ Q and R ′ = P ∨ Q. Then r = r ′ = p ⊔ q; and so P ∧ Q is partly about s iff P ∨ Q is partly about s.

Now suppose R = P ∧ Q is partly about s. Then s overlaps with r = p ⊔ q and so, by Overlap, s overlaps with p or with q and P or Q is partly about s.

Now suppose P is partly about s (the case in which Q is partly about s is similar). Then s overlaps with p and hence with r for R = P ∧ Q and P ∧ Q is partly about s.

This and the subsequent results extend straightforwardly to infinitary conjunctions and disjunctions. The result may also be extended to negation by talking of bilateral propositions instead of unilateral propositions. Say that the bilateral proposition P = (P, P ′) is positively (negatively)partially about the subject-matter s if P (resp. P ′) is partially about s. Then from the previous lemma it immediately follows that:

Theorem 19

For regular non-vacuous propositions P and Q and subject-matter s:

-

(i) ¬P is positively (negatively) partially about s iff P is negatively (positively) partially about s;

-

(ii) P ∧Q is positively (negatively) partially about s iff P or Q is positively (negatively) partially about s; and

-

(iii) P ∨Q is positively (negatively) partially about s iff P or Q is positively (negatively) partially about s.

Now say that the bilateral proposition P is partially about subject-matter s if it is positively or negatively partially about s. Note that P = (P, P ′) will be partially about s just in case s overlaps with the combined subject-matter p ⊔ p ′ of P. From the theorem, we obtain the more general compositionality result.

Corollary 20

For regular nonvacuous propositions P and Q and subject-matter s:

-

(i) ¬P is partially about s iff P is partially about s;

-

(ii) P ∧Q is partially about s iff P or Q is partially about s; and

-

(iii) P ∨Q is partially about s iff P or Q is partially about s.

Ground

We adopt the following definitions from [3]. For verifiable propositions P 1,P 2, ... and Q, we say:

P 1,P 2, ... weakly (fully)grounds Q - in symbols, P 1,P 2, ... ≤ Q - if P 1 ∧ P 2 ∧ ... ≤ d Q;

P weakly partially grounds Q - in symbols,P Q - if for some verifiable P 1,P 2, ..., P, P 1,P 2, ... weakly grounds Q;

P 1,P 2 , ... strictly (fully) grounds Q - in symbols, P 1,P 2, ... < Q - if P 1,P 2, ...weakly grounds Q and Q does not weakly partially ground any of the propositions P 1,P 2, ...;

P strictly partially grounds Q - in symbols, P ≺ Q - if P weakly grounds Q but Q does not weakly ground P.

Although I have given these definitions for the case of unilateral propositions, they are readily extended to the case of bilateral propositions. Note also that it will follow from these definitions that the resulting notions of ground conform to the pure logic of ground, as laid down in [3].

Lemma 21

For regular verifiable propositions P and Q, the following are equivalent:

-

(i) P weakly partially grounds Q

-

(ii) P, P ′ weakly grounds Q for some regular verifiable proposition P ′x

-

(iii) P, Q weakly grounds Q

-

(iv) (P ∧ Q) ∨ Q = Q

-

p \(\sqsubseteq \) q.

Proof

It is evident that (iii) ⇒ (ii) and that (ii) ⇒ (i). Three cases remain: (i) ⇒ (v). Suppose P weakly partially grounds Q, so P ∧ P 1 ∧ P 2 ... ≤ d Q for regular verifiable propositions P 1,P 2, ... . Select p 1 ∈ P 1,p 2 ∈ P 2, ... . Then p ⊔ p 1 ⊔p 2 ⊔ ... ∈ P∧ P 1 ∧P 2 ... ⊆Q; and so p \(\sqsubseteq \) p ⊔p 1 ⊔p 2 ⊔ ... \(\sqsubseteq \) q.

(v) ⇒ (iv) & (iv) ⇒ (iii). By lemma I.13, conditions (iii) and (iv) are equivalent and so it suffices to show (v) ⇒ (iii). To this end, suppose p \(\sqsubseteq \) q and take a p ⊔ q ∈ P∧ Q with p ∈ P and q ∈ Q. We wish to show p ⊔ q ∈ Q. Buts \(q \sqsubseteq p \,\sqcup \, q \sqsubseteq \) p \(\,\sqcup \, q \sqsubseteq \) p ⊔ q \(\sqsubseteq \) q (given p \(\sqsubseteq \) q); and so by Q regular, p ⊔ q ∈ Q.

The most remarkable equivalence here is that weak partial ground (P≼Q) amounts simply to inclusion of subject-matter (p

\(\sqsubseteq \)

q). Note that it follows immediately from this equivalence that P will strictly partially ground Q (P≺Q) just in case there is a proper inclusion of subject-matter (p

q).

q).

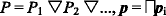

Theorem 22

For regular verifiable P 1 , P 2 , ... and Q, the following are equivalent:

-

(i) P 1 , P 2 , ... strictly grounds Q

-

(ii) P 1 , P 2 , ... weakly grounds Q and each of P i strictly partially grounds Q

-

P 1 , P 2 , ... weakly grounds Q and each p i

q

q

Proof

The equivalence of (i) and (ii) is immediate from the definitions; and the equivalence of (ii) and (iii) follows from the criterion for strict partial ground.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fine, K. A Theory of Truthmaker Content II: Subject-matter, Common Content, Remainder and Ground. J Philos Logic 46, 675–702 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10992-016-9419-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10992-016-9419-5

. So suppose there are some P

1, P

2, ... . Then

. So suppose there are some P

1, P

2, ... . Then  =

=  ..., given that each p

i

is the maximal member of P

i

. But

..., given that each p

i

is the maximal member of P

i

. But  .

. and so P is verifiable. We establish the following further facts in completing the demonstration of (ii):

and so P is verifiable. We establish the following further facts in completing the demonstration of (ii):

by (i) and

by (i) and  ∈ P. (b) Suppose q ∈ P and

∈ P. (b) Suppose q ∈ P and  . Then q is of the form

. Then q is of the form  for some p ∈ P

i

. Since

for some p ∈ P

i

. Since  and P

i

is a regular proposition, p ⊔q

′

∈

P

i

. But then

and P

i

is a regular proposition, p ⊔q

′

∈

P

i

. But then

.

. withP

′

∈

P

i

for some i. But then

withP

′

∈

P

i

for some i. But then  p

p

.

. . Now suppose p ∈ P . Then p is of the form

. Now suppose p ∈ P . Then p is of the form  with P

′

∈

P

i

for some i. So P

′

with P

′

∈

P

i

for some i. So P

′

. But then

. But then  .

. belongs to each P

i

, given that the P

i

are regular, and so p ∈ P.

belongs to each P

i

, given that the P

i

are regular, and so p ∈ P. . But

. But  . For, given any r

i

∈

R, there is a q

i

∈

Q for which r

i

⊔

q

i

∈

P. But

. For, given any r

i

∈

R, there is a q

i

∈

Q for which r

i

⊔

q

i

∈

P. But

q

q