Abstract

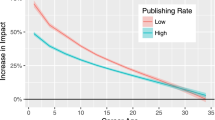

I aim to advance our understanding of the size of scientific specialties. Derek Price’s groundbreaking work has provided us with valuable conceptual tools and data for making progress on this issue. But, I argue that his estimate of 100 scientists per specialty is flawed. He fails to take into account the fact that the average publishing scientist publishes only 3.5 articles throughout her career. Hence, rather than consisting of 100 scientists, I have suggested that specialties are probably somewhat larger, perhaps somewhere between 250 and 600 scientists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Specialties are not the only social unit in science of interest to the sociologist and philosopher of science. Hull (1988) suggests that scientific specialties consist of research teams, as well as competing demes. These smaller groups “provide sympathetic criticism” to scientists as they develop their ideas (p. 366).

Others have offered alternative explanations for the creation of new specialties. Ben-David and Collins (1966/1991), for example, suggest that new specialties are created by scientists looking for career opportunities. They cite the example of the development of experimental psychology in Germany in the 19th century to support their claim. Kuhn (2000), on the other, hand, suggests that new specialties are created by conceptual innovations. Sometimes, a change in theory leads a research community to split into two specialties. See Wray (2005) for a critical discussion of these views of the process of specialty formation.

Menard (1971) acknowledges that specialties are apt to range in size. His calculations, though, are based on many of Price’s assumptions. Menard explicitly notes that his “debt to Professor Price is evident throughout [his book Science: Growth and Change]” (p. 6, Note 2).

I did not pull the number 600 out of thin air. It is the number of members of the Philosophy of Science Association (PSA), the key professional organization for one of the specialties in which I publish. Indeed, this specialty is served for the most part by seven journals: Philosophy of Science, The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science and International Studies in the Philosophy of Science are exclusively philosophy of science journals; Synthese and Erkenntnis publish a large portion of philosophy of science as well as articles in other areas of analytic philosophy; and Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science and Perspectives on Science publish papers in history and sociology of science, as well as the philosophy of science. Hence, these last four journals should only count as fractional journals for the specialty of philosophy of science. I thank Gary Hardcastle for information about the size of the PSA membership.

References

Ben-David, J., & Collins, R. (1966/1991). Social factors in the origins of a new science: The case of psychology. In J. Ben-David (Ed.), Scientific growth: Essays on the social organization and ethos of science (pp. 49–70). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cole, S. (1992). Making science: Between nature and society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ennis, J. G. (1992). The social organization of sociological knowledge: Modeling the intersection of specialties. American Sociological Review, 57, 259–265.

Hull, D. L. (1988). Science as a process: An evolutionary account of the social and conceptual development of science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1996a/1962). Structure of scientific revolutions (3rd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1996b/1969). Postscript. In T. S. Kuhn (Ed.), Structure of scientific revolutions (3rd ed., pp. 174–210). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (2000). In J. Conant & J. Haugeland (Ed.), The road since structure: Philosophical essays, 1970–1993, with an autobiographical interview. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Menard, H. W. (1971). Science: Growth and change. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Merton, R. K., & Garfield, E. (1986). Forward. In D. de S. Price (Ed.), Little science, big science … and beyond (pp. vii–xiii). New York: Columbia University Press.

Price, D. de S. (1986/1963). Little science, big science … and beyond. New York: Columbia University Press.

Wray, K. B. (2005). Rethinking scientific specialization. Social Studies of Science, 35(1), 151–164.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wray, K.B. Rethinking the size of scientific specialties: correcting Price’s estimate. Scientometrics 83, 471–476 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0060-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0060-8