Abstract

In order to efficiently allocate academic resources, an awareness of the properties of the underlying production function’s returns to scale is of crucial importance. For instance, the question arises as to what extent an expansion of a university department’s academic staff would be advisable in order to utilize increasing marginal gains of research production. On the other hand, it is disputable whether an optimal university department size exists. Empirical studies covering these questions render various answers. In this paper, we analyse which properties of returns to scale the Business Administration research of universities in Germany exhibits. On the basis of research data from 2001 until 2009 provided by the Centre for Higher Education, and using Data Envelopment Analysis, we demonstrate that typically sized business schools show nearly constant returns to scale. Furthermore, we observe tendencies of decreasing returns to scale for large-sized business schools. Diverse robustness and sensitivity analyses confirm the validity of our inferred empirical findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Nevertheless, it has to be considered that depending on the examined academic discipline, varying partial activities, i.e. varying partial indicators, are subsumed under the respective total research production. Research production, in turn, certainly only constitutes one partial aspect of a department’s (total) production in favour of a university; especially academic teaching activities remain unconsidered.

On the basis of these absolute indicators, the CHE determines corresponding relative indicators. However, since the exact CHE approach is irrelevant for the subject matter of the present paper, we refrain from an explicit illustration and refer to the appropriate explanations of the CHE (e.g. Berghoff et al. 2011).

However, the quality-weighting for journal articles—in line with the calculation of publication points—had not yet been incorporated into the data acquisition in 2004. Moreover, in 2004 only those publications were included which had at least one professor as (co)author—identified by a BuS-submitted list of all respective professors’ names. From 2007 on, however, all publications featuring at least one post-doctoral scientist as (co)author, have been taken into account.

Relating to Pub-int, there is a difference from the dataset of 2004, too, since this indicator was not part of the CHE indicator set and was not acquired accordingly. Furthermore, due to the lack of Pub-int weighting, there is a certain inhomogeneity between the two publication indicators in both the indicator design and the indicator acquisition. However, because we would like to base our analyses on the original CHE data, we initially forego a conceivable Pub-int weighting analogously to the PP-nat procedure. We address the extent to which such weighting has an impact on the resulting returns to scale in the sensitivity analyses.

A detailed examination concerning the relevance of TPF in research productivity and performance analyses is provided by Rassenhövel (2010, p. 85ff).

At the very least, this conclusion is valid for the considered periods of our analyses. Meanwhile however, methodological approaches in Business Administration studies are increasing as well, requiring considerably more physical resources. For example, this applies to neuropsychological and experimental research approaches.

Compared to deterministic DEA, SFA is more applicable in allowing for randomly scattered data. However, we account for this sensitivity problem of DEA with different robustness and sensitivity analyses.

For further basic information on DEA and corresponding mathematical model descriptions, cf. e.g., Cooper et al. (2007).

First, all deliberations refer to results based on output-oriented DEA models. From a short-term and middle-term point of view, this proves to be plausible, since scientific staff can generally be considered as (almost) fixed in the short run and rather variable in the long run. Accordingly, input-oriented models only make sense for long-term considerations—if at all. Within the scope of the sensitivity analyses later on, we will also address results originating from input-oriented models.

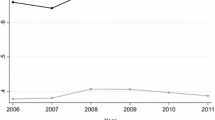

Due to the predefined CHE indicator set, the presented scale efficiencies of 2004 are still based on three outputs (excluding Pub-int). While the calculated efficiency scores in the context of DEA can only increase with the addition of supplementary indicators, scale efficiencies as a quotient of BCC and CCR efficiency score can either increase or decrease. This may basically limit the intertemporal comparability of our scale efficiency analyses. However, our sensitivity analyses indicate that the results and the statements are robust or valid with respect to modifications to the preference relation, which is to say that the exclusion of the Pub-int indicator from the 2007 and 2010 datasets does not produce any notable changes in our results.

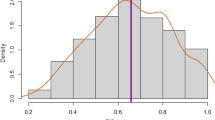

If, however, one generously operationalizes locally constant returns to scale already from a scale efficiency of ≥80 %, a size range results from 8 up to 18.6 professors, in which over all timeframes investigated approximately constant returns to scale can be discovered. For the following analyses, though, we will define such a size range of constant returns to scale more closely, in order to assure a higher robustness of our results.

Note that the number of research assistants is, however, always part of our scale efficiency analyses.

This number (of professors) corresponds to the largest of all top 10 reputable BuSs over the three consecutive timeframes investigated.

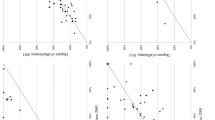

We applied the respective R 2 as the quality criterion for the function approximations. With values of 0.753 (2004), 0.632 (2007) and 0.545 (2010), they all exhibit high levels.

When utilizing all data points for each of the timeframes investigated instead of the interval from 8 up to 28.7 professors focused on here, we observe comparable results. However, the approximation of data points by regression falls off in quality, as measured and revealed by lower R 2 values.

It should be pointed out here that the meaning of a scale efficiency is not comparable with the efficiency score of an original productivity analysis using DEA. A high scale efficiency indicates that the DMU is located in a size range in which the efficient frontiers of the production functions, that are empirically created using DEA by assuming constant and variable returns to scale, are close together. This value does not allow for the derivation of any assertions about the research efficiency of an individual BuS, which is why no concrete efficiency improvement recommendations can be made. Such recommendations rather depend on the specific system of objectives of a BuS and are not part of our paper.

Utilizing DEA certainly involves the advantage that respective weightings of objectives are determined (endogenously) for each BuS individually and most favourably. In this way, taking into account BuS-specific profiles is per se inherent in DEA analyses. Thus, the problem of deviating BuS objectives is already mitigated ex-ante by the method itself.

These two BuSs are not CCR-efficient, merely because BuS 71 exhibits the highest partial efficiency with regard to TPF in 2007; BuS 71 therefore obviously has to represent one benchmarking partner for both of them. However, this does not change the fact that all three BuSs feature untypically high TPF values and thus have to be considered in the scope of sensitivity analyses.

We intentionally decided to exclude the indicator Pub-int from all sensitivity analyses with respect to the preference relation, since this indicator was not raised in 2004. However, for the datasets of 2007 and 2010, we calculated the accordant scale efficiencies both including and excluding Pub-int, respectively. When comparing the resulting scale efficiencies of the cases a)—excluding just one indicator—and b)—excluding this indicator and additionally Pub-int—, then the resulting regression line adds up to y = 0.9469x + 0.0405 (R 2 = 0.8181) in the event of additionally excluding PP-nat, y = 0.9889x + 0.004 (R 2 = 0.9166) in the case of additionally excluding TPF, and y = 1.0133x − 0.0196 (R 2 = 0.9126) if additionally excluding PhD dissertations. According to this, the obtained results are nearly identical, which is why we only illustrate case a) in our sensitivity analysis of this subsection.

The adequacy of using journal impact factors to quantify the outcome of research production is certainly subject to the specific context of application. In this respect, the use of impact factors instead of citations can be accepted for the specific subject matter of Business Administration research, where actually numerous articles are uncited. It is, of course, not valid for a general theoretical perspective in terms of a generally accepted approach for all academic disciplines.

References

Abbot, M., & Doucouliagos, C. (2003). The efficiency of Australian universities: A Data Envelopment Analysis. Economics of Education Review, 22(1), 89–97.

Abramo, G., Cicero, T., & D’Angenlo, C. A. (2011). A field-standardized application of DEA to national-scale research assessment of universities. Journal of Informetrics, 5(4), 618–628.

Abramo, G., Cicero, T., & D’Angelo, C. A. (2012). Revisiting size effects in higher education research productivity. Higher Education, 63(6), 701–717.

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Di Costa, F. (2014). Investigating returns to scope of research fields in universities. Higher Education, 68(1), 69–85.

Ahn, T., Charnes, A., & Cooper, W. W. (1988). Some statistical and DEA evaluations of relative efficiencies of public and private institutions of higher learning. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 22(6), 259–269.

Ahn, H., Dyckhoff, H., & Gilles, R. (2007). Datenaggregation zur Leistungsbeurteilung durch Ranking: Vergleich der CHE- und DEA-Methodik sowie Ableitung eines Kompromissansatzes. Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft, 77(6), 615–643.

Banker, R. D., Charnes, A. C., & Cooper, W. W. (1984). Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in Data Envelopment Analysis. Management Science, 30(9), 1078–1092.

Beasley, J. E. (1990). Comparing university departments. Omega, 18(2), 171–181.

Beasley, J. E. (1995). Determining teaching and research efficiencies. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 46(4), 441–452.

Berghoff, S., Giebisch, P., Hachmeister, C.-D., Hoffmann-Kobert, B., Hennings, M., & Ziegele, F. (2011). Vielfältige Exzellenz 2011: Forschung, Anwendungsbezug, Internationalität, Studierendenorientierung im CHE Ranking. Gütersloh: Centrum für Hochschulentwicklung.

Bonaccorsi, A., & Daraio, C. (2005). Exploring size and agglomeration effects on public research productivity. Scientometrics, 63(1), 87–120.

Bonaccorsi, A., Daraio, C., & Simar, L. (2006). Advanced indicators of productivity of universities: An application of robust nonparametric methods to Italian data. Scientometrics, 66(2), 389–410.

Bort, S., & Schiller-Merkens, S. (2010). Publish or perish. Zeitschrift Führung + Organisation, 79(5), 340–346.

Brandt, T., & Schubert, T. (2013). Is the university model an organizational necessity? Scale and agglomeration effects in science. Scientometrics, 94(2), 541–565.

Breu, T. M., & Raab, R. L. (1994). Efficiency and perceived quality of the nation’s “TOP 25” national universities and national liberal arts colleges: An application of Data Envelopment Analysis to higher education. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 28(1), 33–45.

Chalmers, A. F. (1990). Science and its fabrication. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Charnes, A. C., Cooper, W. W., & Rhodes, E. (1978). Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. European Journal of Operational Research, 2(6), 429–441.

Clermont, M., & Dirksen, A. (2015). The measurement, evaluation, and publication of performance in higher education: An analysis of the CHE research ranking of business schools in Germany from an accounting perspective. Public Administration Quarterly, forthcoming.

Clermont, M., & Dyckhoff, H. (2012a). Erfassung betriebswirtschaftlich relevanter Zeitschriften in Literaturdatenbanken. Betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung und Praxis, 64(3), 324–346.

Clermont, M., & Dyckhoff, H. (2012b). Coverage of Business Administration literature in Google Scholar: Analysis and comparison with EconBiz, Scopus and Web of Science. Bibliometrie – Praxis und Forschung, 1(1), 5/1–5/19.

Cohen, J. E. (1980). Publication rate as a function of laboratory size in a biomedical research institution. Scientometrics, 2(1), 35–52.

Cohen, J. E. (1991). Size, age and productivity of scientific and technical research groups. Scientometrics, 20(3), 395–416.

Cook, W. D., & Zhu, J. (2007). Classifying inputs and outputs in Data Envelopment Analysis. European Journal of Operational Research, 180(2), 692–699.

Cooper, W. W., Seiford, L. M., & Tone, K. (2007). Data Envelopment Analysis: A comprehensive text with models, applications, references and DEA-solver software (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Dyckhoff, H., Clermont, M., Dirksen, A., & Mbock, E. (2013). Measuring balanced effectiveness and efficiency of German business schools’ research performance. Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft, Special Issue, 3(2013), 39–60.

Dyckhoff, H., Rassenhövel, S., & Sandfort, K. (2009). Empirische Produktionsfunktion betriebswirtschaftlicher Forschung: Eine Analyse der Daten des Centrums für Hochschulentwicklung. Zeitschrift für betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung, 61(1), 22–56.

Fandel, G. (2007). On the performance of universities in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany: Government’s redistribution of funds judged using DEA efficiency measures. European Journal of Operational Research, 176(1), 521–533.

Farrell, M. J. (1957). The measurement of productive efficiency. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A (General), 120(3), 253–290.

Frey, B. S. (2007). Evaluierungen, Evaluierungen … Evaluitis. Perspektiven der Wirtschaftspolitik, 8(3), 207–220.

Gilles, R. (2005). Performance Measurement mittels Data Envelopment Analysis: Theoretisches Grundkonzept und universitäre Forschungsperformance als Anwendungsfall. Lohmar: Eul.

Gutenberg, E. (1983). Grundlagen der Betriebswirtschaftslehre. Band I: Die Produktion, 24th edition. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer.

Gutierrez, M. (2007). Messung der Effizienz von Professuren mittels Data Envelopment Analysis. Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft, Special Issue, 5(2007), 101–129.

Jarwal, S. D., Brion, A. M., & King, M. L. (2009). Measuring research quality using the journal impact factor, citations and ‘Ranked journals‘: Blunt instruments or inspired metric? Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management, 31(4), 289–300.

Joerk, C., & Wambach, A. (2013). DFG-Förderung in den Wirtschaftswissenschaften: Fakten und Mythen zur Förderpraxis. Perspektiven der Wirtschaftspolitik, 14(1–2), 99–117.

Johnes, J. (2006). Measuring teaching efficiency in higher education: An application of Data Envelopment Analysis to economic graduates from UK universities 1993. European Journal of Operational Research, 174(1), 443–456.

Johnes, G., & Johnes, J. (1993). Measuring the research performance of UK economics departments: An application of Data Envelopment Analysis. Oxford Economic Papers, 45(2), 332–347.

Johnston, R. (1994). Effects of resource concentration on research performance. Higher Education, 28(1), 25–37.

Kao, C., & Hung, H.-T. (2008). Efficiency analysis of university departments: An empirical study. Omega, 36(4), 653–664.

Kieser, A. (2012). JOURQUAL: Der Gebrauch, nicht der Missbrauch, ist das Problem. Oder: Warum Wirtschaftsinformatik die beste deutschsprachige betriebswirtschaftliche Zeitschrift ist. Die Betriebswirtschaft, 72(1), 93–110.

Kyvik, S. (1995). Are big university departments better than small ones? Higher Education, 30(3), 295–304.

Laband, D. N., & Lentz, B. F. (2003). New estimates of scale and scope in higher education. Southern Economic Journal, 70(1), 72–183.

Longlong, H., Fengliang, L., & Weifang, M. (2009). Multi-product total cost functions for higher education: The case of Chinese research universities. Economics of Education Review, 28(4), 505–511.

Madden, G., Savage, S., & Kemp, S. (1997). Measuring public sector efficiency: A study of economics departments at Australian Universities. Education Economics, 5(2), 153–168.

Marginson, S., & van der Welde, M. (2007). To rank or to be ranked: The impact of global rankings in higher education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(3–4), 206–329.

Meng, W., Zhang, D., Qi, L., & Liu, W. (2008). Two-level DEA approaches in research evaluation. Omega, 36(6), 950–957.

Nosek, B. A., Graham, J., Lindner, N. M., Kesebir, S., Hawkins, C., Hahn, C., & Tenney, E. R. (2010). Cumulative and career-stage citation impact of social-personality psychology programs and their members. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(10), 1283–1300.

Rassenhövel, S. (2010). Performancemessung im Hochschulbereich: Theoretische Grundlagen und empirische Befunde. Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Ray, S. C., & Jeon, Y. (2008). Reputation and efficiency: A non-parametric assessment of America’s top-rated MBA programs. European Journal of Operational Research, 189(1), 245–268.

Schrader, U., & Hennig-Thurau, T. (2009). VHB-Jourqual2: Methods, results, and implications of the German Academic Association for Business Research’s journal ranking. Business Research, 2(2), 180–204.

Stolz, I., Hendel, D. D., & Horn, A. S. (2010). Ranking of rankings: Benchmarking twenty-five higher education ranking systems in Europe. Higher Education, 60(5), 507–528.

Tavenas, F. (2004). Quality assurance: A reference system for indicators and evaluation procedures. Brussels: European University Association.

Tomkins, C., & Green, R. (1988). An experiment in the use of Data Envelopment Analysis for evaluating the efficiency of UK university departments of accounting. Financial Accountability & Management, 4(2), 147–164.

Usher, A., & Savino, M. (2006). A world of difference: A global survey of university league tables. Toronto: Educational Policy Institute.

Van der Wal, R., Fischer, A., Marquiss, M., Redpath, S., & Wanless, S. (2009). Is bigger necessarily better for environmental research? Scientometrics, 78(2), 317–322.

Van Raan, A. F. J. (1996). Advanced bibliometric methods as quantitative core of peer review based evaluation and foresight exercises. Scientometrics, 36(3), 397–420.

Von Tunzelmann, N., Ranga, M., Martin, B., & Geuna, A. (2003). The effects of size on research performance: A SPRU review. Brighton: Science Policy Research Project.

Acknowledgments

The project underlying this article was funded by the Federal Ministry for Education and Research (Germany) under Grant Number 01PW11014. The responsibility for the contents of the article lies with the authors. In addition, the authors would like to thank two anonymous reviewers whose comments helped crafting the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clermont, M., Dirksen, A. & Dyckhoff, H. Returns to scale of Business Administration research in Germany. Scientometrics 103, 583–614 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1561-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1561-2

Keywords

- Business Administration research

- Centre for Higher Education

- Data Envelopment Analysis

- Empirical production function

- Returns to scale

- Scale efficiency