Abstract

How do research fields evolve? This study confronts this question here by developing an inductive analysis based on emerging research fields of human microbiome, evolutionary robotics and astrobiology (also called exobiology). Data analysis considers papers associated with subject areas of authors from starting years to 2017 per each research field under study. Findings suggest some empirical properties of the evolution of research fields: the first property states that the evolution of a research field is driven by few disciplines (3–5) that generate more than 80% of documents (concentration of scientific production); the second property states that the evolution of research fields is path-dependent of critical disciplines: they can be parent disciplines that have originated the research field or new disciplines emerged during the evolution of science; the third property states that the evolution of research fields can be also due to a new discipline originated from a process of specialization within applied or basic sciences and/or convergence between disciplines. Finally, the fourth property states that the evolution of specific research fields can be due to both applied and basic sciences. These results here can explain and generalize some characteristics of the evolution of scientific fields in the dynamics of science. Overall, then, this study begins the process of clarifying and generalizing, as far as possible, the general properties of the evolution of research fields to lay a foundation for the development of sophisticated theories of the evolution of science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

cf., Coccia and Wang (2016, p. 2059) for categorization of applied and basic fields of research.

“ ‘normal science’ means research firmly based upon one or more past scientific achievements that some particular scientific community acknowledges for a time as supplying the foundation for its further practice’’ (Kuhn 1962, p. 10, original emphasis).

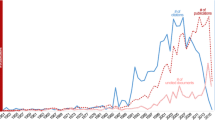

x-axis indicates the time (years).

References

Adams, J. (2012). The rise of research networks. Nature, 490(7420), 335–356.

Adams, J. (2013). The fourth age of research. Nature, 497(7451), 557–560.

Allison, P. D., & Stewart, J. A. (1974). Productivity differences among scientists: Evidence for accumulative advantage. American Sociological Review, 39(4), 596–606.

Andersen, H. (1998). Characteristics of scientific revolutions. Endeavour, 22(1), 3–6.

Börner, K., Glänzel, W., Scharnhorst, A., & den Besselaar, P. V. (2011). Modeling science: studying the structure and dynamics of science. Scientometrics, 89, 347–348.

Börner, K., & Scharnhorst, A. (2009). Visual conceptualizations and models of science. Journal of Informetrics, 3, 161–172.

Boyack, K. W. (2004). Mapping knowledge domains: Characterizing PNAS. Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences of The United States of America (PNAS), 101(suppl. 1), 5192–5199.

Boyack, K. W., Klavans, R., & Börner, K. (2005). Mapping the backbone of science. Scientometrics, 64(3), 351–374.

Coccia, M. (2005). A scientometric model for the assessment of scientific research performance within public institutes. Scientometrics, 65(3), 307–321.

Coccia, M. (2011). The interaction between public and private R&D expenditure and national productivity. Prometheus, 29(2), 121–130.

Coccia, M. (2014). Structure and organisational behaviour of public research institutions under unstable growth of human resources. International Journal of Services Technology and Management, 20(4/5/6):251.

Coccia, M. (2016a). Radical innovations as drivers of breakthroughs: characteristics and properties of the management of technology leading to superior organisational performance in the discovery process of R&D labs. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 28(4), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2015.1095287.

Coccia, M. (2016b). Sources of technological innovation: Radical and incremental innovation problem-driven to support competitive advantage of firms. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 29(9), 1048–1061.

Coccia, M. (2017). The source and nature of general purpose technologies for supporting next K-waves: Global leadership and the case study of the U.S. Navy’s Mobile User Objective System. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 116(March), 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.05.019.

Coccia, M., & Bozeman, B. (2016). Allometric models to measure and analyze the evolution of international research collaboration. Scientometrics, 108(3), 1065–1084.

Coccia, M., & Cadario, E. (2014). Organisational (un) learning of public research labs in turbulent context. International Journal of Innovation and Learning, 15(2), 115.

Coccia, M., & Falavigna, G., & Manello, A. (2015). The impact of hybrid public and market-oriented financing mechanisms on the scientific portfolio and performances of public research labs: A scientometric analysis. Scientometrics, 102(1), 151–168.

Coccia, M., & Rolfo, S. (2009). Project management in public research organisations: Strategic change in complex scenarios. International Journal of Project Organisation and Management, 1(3), 235.

Coccia, M., & Rolfo, S. (2010). New entrepreneurial behaviour of public research organisations: Opportunities and threats of technological services supply. International Journal of Services Technology and Management, 13(1/2), 134.

Coccia, M., & Rolfo, S. (2013). Human resource management and organizational behavior of public research institutions. International Journal of Public Administration, 36(4), 256–268.

Coccia, M., & Wang, L. (2016). Evolution and convergence of the patterns of international scientific collaboration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(8), 2057–2061. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1510820113.

Crane, D. (1972). Invisible colleges: Diffusion of knowledge in scientific communities. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

David, P. A. (1994). Positive feedbacks and research productivity in science: Reopening another black box. In O. Granstrand (Ed.), Economics of technology. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

de Beaver, B. D., & Rosen, R. (1978). Studies in scientific collaboration. Part 1. The professional origins of scientific co-authorship. Scientometrics, 1, 65–84.

De Solla Price, D. J. (1986). Little science, big science… and beyond. Columbia University Press, New York, Ch. 3.

Dogan, M., & Pahre, R. (1990). Creative marginality: Innovation at the intersections of social sciences. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Fanelli, D., & Glänzel, W. (2013). Bibliometric evidence for a hierarchy of the sciences. PLoS ONE, 8(6), e66938. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066938.

Floreano, D., Husbands, P., & Nolfi, S. (2008). Evolutionary Robotics. In B. Siciliano & O. Khatib (Eds.), Springer handbook of robotics. Berlin: Springer.

Fox, M. F. (1983). Publication productivity among scientists: A critical review. Social Studies of Science, 13(2), 285–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631283013002005.

Frame, J. D., & Carpenter, M. P. (1979). International research collaboration. Social Studies of Science, 9(4), 481–497.

Freedman, P. (1960). The principles of scientific research (First edition 1949). London: Pergamon Press.

Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwatzman, S., Scott, P., & Trow, M. (1994). The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary society. London: Sage Publications.

Guimera, R., Uzzi, B., Spiro, J., & Amaral, L. (2005). Team assembly mechanisms determine collaboration network structure and team performance. Science, 308(5722), 697–702.

International Journal of Astrobiology. (2018). https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-journal-of-astrobiology. Accessed May 2018.

Jamali, H. R., & Nicholas, D. (2010). Interdisciplinarity and the information-seeking behavior of scientists. Information Processing and Management, 46, 233–243.

Jeffrey, P. (2003). Smoothing the Waters: Observations on the Process of Cross-Disciplinary Research Collaboration. Social Studies of Science, 33(4), 539–562.

Kitcher, P. (2001). Science, truth, and democracy, Chps. 5–6. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Klein, J. T. (1996). Crossing boundaries. Knowledge, disciplinarities and interdisciplinarities. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions (2nd enlarged ed.). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Lakatos, I. (1978). The Methodology of scientific research programmes: Philosophical papers (Vol. 1). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Latour, B. (1987). Science in action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Latour, B., & Woolgar, S. (1979). Laboratory life: The social construction of scientific facts. London and Beverly Hills: Sage.

Lederberg, J. (1960). Exobiology: Approaches to life beyond the earth. Science, 132(3424), 393–400.

Lee, S., & Bozeman, B. (2005). The impact of research collaboration on scientific productivity. Social Studies of Science, 35(5), 673–702.

Levin, S. G., & Stephan, P. E. (1991). Research productivity over the life cycle: Evidence for academic scientists. American Economic Review, 81(1), 114–132.

Merton, R. K. (1957). Priorities in scientific discovery: A chapter in the sociology of science. American Sociological Review, 22(6), 635–659. https://doi.org/10.2307/2089193.

Merton, R. K. (1968). The Matthew Effect in Science. Science, 159(3810), 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.159.3810.56.

Morillo, F., Bordons, M., & Gómez, I. (2003). Interdisciplinarity in Science: A Tentative Typology of Disciplines and Research Areas. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 54(13), 1237–1249.

Mulkay, M. (1975). Three models of scientific development. The Sociological Review, 23, 509–526.

NASA. (2018a). Astrobiology at NASA-Life in the Universe. https://astrobiology.nasa.gov/about/history-of-astrobiology/.

NASA. (2018b). NASA Astrobiology Institute (NAI). https://nai.nasa.gov/about/. Accessed July 2018.

NASA. (2018c). Exobiology. https://astrobiology.nasa.gov/research/astrobiology-at-nasa/exobiology/. Accessed July 2018.

Newman, M. E. J. (2001). The structure of scientific collaboration networks. Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences of The United States of America (PNAS), 98(2), 404–409.

Newman, M. E. J. (2004). Coauthorship networks and patterns of scientific collaboration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), 101(suppl. 1), 5200–5205.

Pan, R. K., Kaski, K., & Fortunato, S. (2012). World citation and collaboration networks: Uncovering the role of geography in science. Scientific Reports, 2(902), 1–7.

Popper, K. (1959). The logic of scientific discovery. London: Hutchinson.

Ramsden, P. (1994). Describing and explaining research productivity. Higher Education, 28, 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01383729.

Relman, D. A. (2002). New technologies, human-microbe interactions, and the search for previously unrecognized pathogens. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 186(SUPPL. 2), S254–S258.

Riesch, H. (2014). Philosophy, history and sociology of science; Interdisciplinary and complex social identities. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 48, 30–37.

Rucker, R. B. (1980). Towards robot consciousness. Speculations in Science and Technology, 3(2), 205–217.

Scharnhorst, A., Börner, K., & Besselaar, P. (2012). Models of science dynamics: Encounters between complexity theory and information sciences. Dordrecht: Springer.

Scopus. (2018). https://www.scopus.com/search/form.uri?zone=TopNavBar&origin=sbrowse&display=basic. Accessed December 2018.

Shanahan, F. (2002). The host-microbe interface within the gut. Bailliere’s Best Practice and Research in Clinical Gastroenterology, 16(6), 915–931.

Simonton, D. K. (2002). Great psychologists and their times: Scientific insights into psychology’s history. Washington DC: APA Books.

Simonton, D. K. (2004). Psychology’s status as a scientific discipline: its empirical placement within an implicit hierarchy of the sciences. Review of General Psychology, 8(1), 59–67.

Small, A. W. (1905). General sociology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

Small, H. (1999). Visualizing science by citation mapping. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 50(3), 799–813.

Smith, L. D., Best, L. A., Stubbs, D. A., Johnston, J., & Bastiani, A. A. (2000). Scientific graphs and the hierarchy of the sciences: A Latourian survey of inscription practices. Social Studies of Science, 30(1), 73–94.

Stephan, P. E. (1996). The economics of science. Journal of Economic Literature, 34(3), 1199–1235.

Stephan, P. E., & Levin, S. G. (1992). How science is done; Why science is done. In P. Stephan & S. Levin (Eds.), Striking the Mother Lode in science: The importance of age, place and time, Chapter 2 (pp. 11–24). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Storer, N. W. (1967). The hard sciences and the soft: Some sociological observations. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 55(1), 75–84.

Storer, N. W. (1970). The internationality of science and the nationality of scientists. International Social Science Journal, 22(1), 80–93.

Sun, X., Kaur, J., Milojević, S., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2013). Social dynamics of science. Scientific Reports, 3(1069), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01069.

The American Microbiome Institute. (2015). http://www.microbiomeinstitute.org/humanmicrobiome. Accessed, 20 April, 2018.

Tijssen, R. J. W. (2010). Discarding the ‘Basic Science/Applied Science’ dichotomy: A knowledge utilization triangle classification system of research journals. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(9), 1842–1852.

van Raan, A. F. J. (2000). On growth, ageing, and fractal differentiation of science. Scientometrics, 47, 347–362.

Wagner, C. (2008). The new invisible college: Science for development. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Woods. E. B. (1907). Progress as a sociological concept. American Journal of Sociology, 12(6), 779–821. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2762650.

Wuchty, S., Jones, B. F., & Uzzi, B. (2007). The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science, 316(1036), 1036–1039.

Young, R. S., & Johnson, J. L. (1960). Basic research efforts in astrobiology. IRE Transactions on Military Electronics, MIL-4(2), 284–287.

Acknowledgements

The research in this paper was conducted while the author was a visiting scholar of the Center for Social Dynamics and Complexity at the Arizona State University funded by CNR - National Research Council of Italy and The National Endowment for the Humanities (Research Grant No. 0003005-2016). I thank the fruitful suggestions and comments by Ken Aiello, Sara I. Walker and seminar participants at the Beyond-Center for Fundamental Concepts in Science (Arizona State University in Tempe, USA). Older versions of this paper circulated as working papers. The author declares that he has no relevant or material financial interests that relate to the research discussed in this paper. Usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coccia, M. General properties of the evolution of research fields: a scientometric study of human microbiome, evolutionary robotics and astrobiology. Scientometrics 117, 1265–1283 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2902-8

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2902-8

Keywords

- Research fields

- Evolution of science

- Dynamics of science

- Convergence in science

- Applied sciences

- Basic sciences

- Human microbiome

- Evolutionary robotics

- Astrobiology

- Exobiology