Abstract

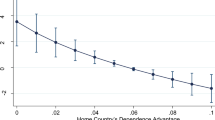

Encouraged by the emergence of a new and growing literature on the use of trademark data as complementary indicators of innovation, this paper strengthens the case for such use by offering both qualitative and quantitative evidence in its support. Based on two large trademark and patent databases built for this purpose, the paper makes the argument that careful use of trademark data can improve our understanding of innovation processes across all sectors of the economy. Our databases generate a high correlation coefficient between patents and trademarks in four different scales of aggregation: firm, sector, country, and global. We argue that the combined use of patent and trademark data is better at capturing the whole gamut of innovation that takes place in the economy than the standard patent data alone. We embed our argument and analysis throughout in the main structural changes that have occurred in the global economy since the latter part of the twentieth century. We find that in certain cases, e.g. in service sectors, in sectors where patents are not widely used, and in the case of exporting entities from developing countries, trademark data are better at capturing the extent of technological and non-technological innovation that occurs therein.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

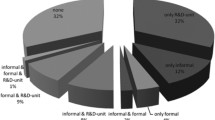

When a new product or service is developed, firms are faced with the choice of possible appropriability mechanism. Patents, secrecy, lead-time advantage on competitors and trademarks are all different ways that enable firms to accrue benefits from the new or improved products they bring to the market (Teece, 1986). Most of these appropriability mechanisms have been analyzed in the literature on innovation and industrial economics, especially patents.

The Community Innovation Survey (CIS) is carried out by EU members every two years. The CIS is a survey of innovation in enterprises and is based on Oslo Manual methodology. It provides information regarding the types of innovation and innovative activities e.g. R&D and appropriability. For further information see http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/.

TRIPS stands for Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights. Developing countries that did not offer pharmaceutical patents prior to TRIPS were allowed a period of transition to comply with TRIPS until 2005 (and later for less-developed countries).

According to this study, copyrights and confidentiality agreements are the legal mechanisms of appropriability most frequently used by firms to protect their innovations.

Even in China, ‘the factory of the world’, services accounted for over 51% of GDP in 2015.

See Gatrell and Ceh (2003) for a more detailed description of the available information regarding trademarks in UPSTO database.

It is important to note that the database includes all the trademarks prior to 1990 that have been digitised. As can be seen in Fig. 1, there are no gaps in the time series.

The PATSTAT is a database maintained by the European Patent Office (EPO) that covers about 70 million patents from about 90 patent offices worldwide (notably, this includes the USPTO, too).

More precisely the tables TLS201_APPLN, TLS211_PAT_PUBLN, TLS206_PERSON, TLS207_PERS_APPLN, TLS208_DOC_STD_NMS.

The NACE class of the assignee in the patent database was retrieved from the Orbis database. The Orbis database is organized by the Bureau van Dijk and captures, treats and standardises data from a wide range of sources to provide economic and financial information on 220 million companies across the globe.

The higher number of Nice classification occurs because more than one class can be assigned to one trademark.

Established to facilitate the international application of trademarks, the Madrid International System is relatively recent, especially in light of the long timeframe our database covers. This does not pose issues for our analysis of non-resident trademarks, however, because the latter are distinguished by the owners/applicants not being US-residents, regardless of the way in which the trademark application was processed by the USPTO.

Changes in the economic activities and organisation in some advanced industrialised countries during the 1907s set in motion a clear shift of their economic make-up from industry-based to knowledge-based economies. OECD figures confirm that the contribution of high-tech sectors, including services, to the economic performance of most developed countries has increased substantially since the 1970s (Dutfield, 2003).

A ten years range was adopted in this case rather than the more commonly used five years range so as to facilitate the comparison of total registrations between periods. Only the top ten firm ranking are shown due to space limitation. The full owner list can be available by request to the corresponding author.

Patents registered in a country by non-residents are commonly related to inventions developed abroad. The product in question is generally not the result of domestic innovative efforts. In the same way, a trademark registration by non-resident might be related to a product developed outside the country.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s the two countries, alongside Mexico, negotiated the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), in force since 1994.

According to US census data presented by a BBC report ‘Trade War’, 10 May 2019, available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-48196495.

This finding is borne out when adopting a sectoral focus, too. Focusing on the manufacture of basic pharmaceutical products and pharmaceutical preparations (NACE codes 2110, and 2120) and on the manufacture of computer and electronic components (NACE codes 2611, 2612, 2620, and 2630), we find a high correlation coefficient between the total number of patents and trademarks for each country-year.

We refer to other entities that are not firms, e.g. universities and research institutions (and, of course, individuals); due to changes in intellectual property laws, initially in the US during the 1980s and later in many other countries, public and private–public entities of this kind are often granted patent protection.

For a detailed description of the Nace sectors, please see Sect. "Analyzing the trademark database: main findings".

Inly firms hhat had at least one patent and one trademark in the USPTO during the period under analysis were included..

Generics and biosimilars are almost identical versions of patented and already approved medicines, the difference between the two being that a biosimilar is a version of a biological medicine, whose active substance is made of a living organism, rather than a chemical composition as is the case of non-biological medicines.

The generics entry prices tend to be 20–80% less than that of the original drug.

E.g. Ranbaxy (India) and GlaxoSmithKline (UK) signed a multi-year R&D collaboration agreement in in respiratory and anti-infectives medicines in 2003.

References

Ahamed, Z., Inohara, T., & Kamoshida, A. (2013). The Servitization of Manufacturing: An Empirical Case Study of IBM Corporation. International Journal of Business Administration, 4(2), 18.

Bryan, D., Rafferty, M., & Wigan, D. (2017). Capital unchained: Finance, intangible assets and the double life of capital in the offshore world. Review of International Political Economy, 24(1), 56–86.

Carlton, D., & Perloff, J. (2005). Modern Industrial Organization. Pearson/Addison Wesley.

Castaldi, C., Block, J., & Flikkema, M. J. (2020). Editorial: why and when do firms trademark? Bridging perspectives from industrial organisation, innovation and entrepreneurship. Industry and Innovation. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2019.1685376

Chudnovsky, D. (1983). Patents and Trademarks in Pharmaceuticals. World Development, 11(3), 187–193.

Degrazia, C. A. W., Myers, A., & Toole, A. A. (2020). Innovation activities and business cycles: are trademarks a leading indicator? Industry and Innovation, 27(1–2), 184–203.

Dutfield, G. (2003). Intellectual Property and the Life Sciences Industries: A Twentieth Century History. Dartmouth Publishing.

Economides, N. (1992). The Economics of Trademarks. Trademark. Reporter, 78, 523–539.

Euipo (2021). Intellectual property rights and firm performance in the European Union: Firm-level analysis report. (https://euipo.europa.eu/tunnel-web/secure/webdav/ guest/document_library/observatory/documents/reports/IPContributionStudy/IPR_firm_performance_in_EU/2021_IP_Rights_and_firm_performance_in_ the_EU_en.pdf)

Eurostat (2008). NACE Rev.2: Statistical classification of economic activites in the European Community, Eurostat Methodologies and Working papers, ISSN 1977–0375.

Flikkema, M., De Man, A.-P., & Castaldi, C. (2014). Are Trademark Counts a Valid Indicator of Innovation? Results of an In-Depth Study of New Benelux Trademarks Filed by SMEs. Industry & Innovation, 21(4), 310–331.

Flikkema, M., Castaldi, C., De Man, A. P., & Seip, M. (2019). Trademarks’ relatedness to product and service innovation: A branding strategy approach. Research Policy, 48(6), 1340–1353.

Florida, R. (2002). The Rise of the Creative Class. And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books.

Freeman, C., & Louçã, F. (2001). As time goes by: From the industrial revolutions and to the information revolution. Oxford University.

Gatrell, J. D., & Ceh, S. L. B. (2003). Trademark Data as Economic Indicator: The United States, 1996–2000. The Great Lakes Geographer, 10(1), 46–56.

Gotsch, M., & Hipp, C. (2012). Measurement of innovation activities in the knowledge-intensive services industry: A trademark approach. Service Industries Journal, 32(13), 2167–2184.

Graham, S. J. H., et al. (2013). The USPTO trademark case files dataset: Descriptions, lessons, and insights. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 22(4), 669–705.

Griliches, Z. (1990). Patent statistics as economic indicator: A survey. Journal of Economic Literature, 28(3301), 1324–1330.

Jaffe, A. B., & Lerner, J. (2006). Innovation and its Discontents. Capitalism and Society. https://doi.org/10.2202/1932-0213.1006

Jessop, R. (2002). The Future of the Capitalist State. Polity Press.

Jungmittag, A., & Reger, A. (2000). Dynamics of the Markets and Market Structure. In A. Jungmittag, G. Reger, & T. Reiss (Eds.), Changing Innovation in the Pharmaceutical Industry: globalization and new ways of drug development. Berlin: Springer.

Kutscher, R. E., & Personick, V. A. (1986). Deindustrialization and the shift to services Monthly Labor Review / U.S. Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 109, 3–13.

Levin, R. C., Klevorick, A. K., Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (1987). Appropriating the Returns from Industrial Research and Development. Brookings Paper- on Economic Activity, 3, 783–831.

Llerena, P., & Millot, V. (2020). Are two better than one? Modelling the complementarity between patents and trademarks across industries. Industry and Innovation, 27(1–2), 52–79.

Lopez, A. Innovation and appropriability, empirical evidence and research agenda. In: The Economics of Intellectual Property. Suggestions for Further Research in Developing Countries and Countries with Economies in Transition. [s.l: s.n.]. p. 1–40.

Mendonça, S., Pereira, T. S., & Godinho, M. M. (2004). Trademarks as an indicator of innovation and industrial change. Research Policy, 33(9), 1385–1404.

Millot, V. 2009. Trademarks as an Indicator of Product and Marketing Innovations, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, 2009/06, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/224428874418

Muzaka, V. (2011). The Politics of Intellectual Property Rights and Access to Medicines. Palgrave MacMillan.

Muzaka, V. (2013). Prizes for Pharmaceuticals? Mitigating the Social Ineffectiveness of the Current Pharmaceutical Patent Arrangement, Third World Quarterly, 34(1), 151–169.

Ribeiro, L. C., Ruiz, R. M., Bernardes, A. T., & Albuquerque, E. M. (2010). Matrices of science and technology interactions and patterns of structured growth: Implications for development. Scientometrics (print), 83, 55–75.

Ribeiro, L. C., Kruss, G., Britto, G., Bernardes, A. T., & Albuquerque, E. M. (2014). A methodology for unveiling global innovation networks: patent citations as clues to cross border knowledge flows. Scientometrics, 101(1), 61–83.

Ribeiro, L. C.; dos Santos, U.; Muzaka, V. (2017) Trademarks as an Indicator of Innovation: Towards a Fuller Picture ; Texto Para Discussão n. 571, Cedeplar-UFMG. Available at http://www.cedeplar.ufmg.br/pesquisas/td/TD%20571.pdf

Rodrik, D. Premature Deindustrialization, Working Paper No. 20935, National Bureau of Economic Research, MA: Cambridge, 2015.

Sandner, P. G., & Block, J. (2011). The market value of R & D, patents, and trademarks. Research Policy, 40(7), 969–985.

Sherer, F. .; Ross, D. Industrial market structure and economic performance. [s.l.] Houghton Mifflin, 1990.

Tarabusi, C. C., & Vickery, G. (1998). Globalisation in the pharmaceutical industry. International Journal of Health Services, 28(1), 67–105.

Teece, D. J. (1986). Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licencing and public policy. Research Policy, 15(February), 285–305.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Brazilian agencies CAPES, CNPq (459627/20147), and FAPEMIG and Britsh Academy (NMG2R2\100168). An embryonic version of this work was published as working in progress paper at Ribeiro et al. (2017). The authors would like to thank the Editorial Coordinator and the reviewers for their insightful criticisms, comments, and suggestions on an earlier version of this paper. This revised version owes a great deal to their input.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix I

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ribeiro, L.C., dos Santos, U.P. & Muzaka, V. Trademarks as an indicator of innovation: towards a fuller picture. Scientometrics 127, 481–508 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04197-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04197-2