Abstract

We propose a dynamic logic of lying, wherein a ‘lie that \(\varphi \)’ (where \(\varphi \) is a formula in the logic) is an action in the sense of dynamic modal logic, that is interpreted as a state transformer relative to the formula \(\varphi \). The states that are being transformed are pointed Kripke models encoding the uncertainty of agents about their beliefs. Lies can be about factual propositions but also about modal formulas, such as the beliefs of other agents or the belief consequences of the lies of other agents. We distinguish two speaker perspectives: (Obs) an outside observer who is lying to an agent that is modelled in the system, and (Ag) an agent who is lying to another agent, and where both are modelled in the system. We distinguish three addressee perspectives: (Cred) the credulous agent who believes everything that it is told (even at the price of inconsistency), (Skep) the skeptical agent who only believes what it is told if that is consistent with its current beliefs, and (Rev) the belief revising agent who believes everything that it is told by consistently revising its current, possibly conflicting, beliefs. The logics have complete axiomatizations, which can most elegantly be shown by way of their embedding in what is known as action model logic or in the extension of that logic to belief revision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

25 July 2018

The original publication of the article is missing the funding information.

25 July 2018

The original publication of the article is missing the funding information.

25 July 2018

The original publication of the article is missing the funding information.

25 July 2018

The original publication of the article is missing the funding information.

Notes

Strictly binding formal belief preconditions to these terms is intended as a strong barrier to avoid pitfalls and digressions into philosophy and epistemology. This is necessary because their everyday usage is ambiguous. We have tried to stay close to dictionary meanings and reported usage. This footnote reports our findings. ‘Truthful’ is synonymous with ‘honest’. Dictionaries do not make a difference between an agent telling the truth and an agent believing that it is telling the truth. A modal logician has to make a choice. We mean the latter, exclusively. A truthful announcement may therefore not be a true announcement. It is tempting, when looking for a single term, to call a truthful agent a truthteller (a somewhat archaic usage) but that would imply that we would not require a truthteller to tell the truth, maybe stretching usage too far. So we did not, and stick to ‘truthful agent’. The dictionary meaning for the verb bluff is ‘to cause to believe what is untrue’ or ‘to deceive or to feign’. Feigning belief in \(p\) means suggesting belief in \(p\), for example by saying that you believe it, even if this is not the case. That corresponds to \(\lnot B_ap\) as precondition. However, this would make lying a form of bluffing, as \(B_a\lnot p\) implies \(\lnot B_ap\). It is common and according to Gricean conversational norms that saying something that you believe to be false is worse than (or, at least, different from) saying something that you do not believe to be true. This brings us to \(\lnot B_ap\wedge \lnot B_a\lnot p\) (\(\wedge \) is conjunction), equivalent to \(\lnot (B_ap\vee B_a\lnot p)\).

Suppose that you believe that \(\lnot p\) and that you lie that \(p\). Later, you find out that your belief was mistaken because \(p\) was really true. You can then with some justification say “Ah, so I was not really lying.”

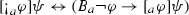

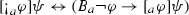

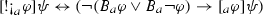

Alternatively, we can take \([_a\varphi ]\) as a primitive operator of the logic and define truthtelling, lying and bluffing by abbreviation as, respectively, \([!_a\varphi ]\psi \leftrightarrow (B_a\varphi \rightarrow [_a\varphi ]\psi )\),

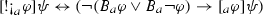

, and

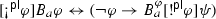

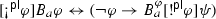

, and  . We then need two axioms only, namely \([_a\varphi ] B_a\psi \leftrightarrow B_a[_a\varphi ] \psi \) and \([_a\varphi ] B_b\psi \leftrightarrow B_b(B_a\varphi \rightarrow [_a\varphi ] \psi )\). This suggestion is from Emiliano Lorini.

. We then need two axioms only, namely \([_a\varphi ] B_a\psi \leftrightarrow B_a[_a\varphi ] \psi \) and \([_a\varphi ] B_b\psi \leftrightarrow B_b(B_a\varphi \rightarrow [_a\varphi ] \psi )\). This suggestion is from Emiliano Lorini.From \(\lnot (B_ap\vee B_a\lnot p)\) follows \(\lnot B_ap\), and with negative introspection we get \(B_a\lnot B_ap\).

Reported in Hales (2011), an \(adf\) is a multi-agent generalization of the (single-agent) disjunctive form as in Meyer and van der Hoek (1995), p. 35 (where it is called \(\mathcal{S 5}\) normal form), and a special case of the disjunctive form as in Agostino and Lenzi (2008). An \(adf\) contains no stacks of \(B_a\) operators without an intermediary \(B_b\) operator for another agent, i.e., if \(B_a\chi \) is a subformula of an \(adf\) and \(B_a\chi ^{\prime \prime }\) is a subformula of \(\chi \) then there is an agent \(b\ne a\) and a \(\chi ^{\prime }\) such that \(B_b\chi ^{\prime }\) is a subformula of \(\chi \) and \(B_a\chi ^{\prime \prime }\) is a subformula of \(\chi ^{\prime }\).

A well-preorder is a well-founded preorder. A preorder is a reflexive and transitive relation. A relation is well-founded if every non-empty subset of the domain has a minimal element.

The former represents weak belief and the latter true strong belief. There are yet other epistemic operators in this setting: safe belief, conditional belief,\(\ldots \) We restrict our presentation to (weak) belief.

Given a plausibility epistemic model \(M\) and a state \(s\) in its domain, define \(R_a^\varphi \) as: \((s, t) \in R_a^\varphi \) iff [\(s\sim _at\), \(t\le _at^{\prime }\) for all \(t^{\prime }\) such that \(s\sim _at^{\prime }\), and \(M,t\models \varphi \)], and define the semantics of \(B_a^\varphi \) as: \(M,s\models B_a^\varphi \psi \) iff \(M,t\models \psi \) for all \(t\) such that \((s,t)\in R_a^\varphi \). We now have that

. The axioms for plausible agent lying are more complex (they also involve conditional knowledge modalities).

. The axioms for plausible agent lying are more complex (they also involve conditional knowledge modalities).

References

Ågotnes, T., & van Ditmarsch, H. (2011). What will they say?—Public announcement games. Synthese, 179(S.1), 57–85.

Alchourrón, C. E., Gärdenfors, P., & Makinson, D. (1985). On the logic of theory change: Partial meet contraction and revision functions. Journal of Symbolic Logic, 50, 510–530.

Aucher, G. (2005). A combined system for update logic and belief revision. In Proceedings of the 7th PRIMA, LNAI 3371 (pp. 1–17). Heidelberg: Springer.

Aucher, G. (2008). Consistency preservation and crazy formulas in BMS. In Proceedings of the 11th JELIA, LNCS 5293 (pp. 21–33). Heidelberg: Springer.

Baltag, A. (2002). A logic for suspicious players: Epistemic actions and belief updates in games. Bulletin of Economic Research, 54(1), 1–45.

Baltag, A., Moss, L. S., & Solecki, S. (1998). The logic of public announcements, common knowledge, and private suspicions. In Proceedings of the 7th TARK (pp. 43–56).

Baltag, A., & Smets, S. (2008a). The logic of conditional doxastic actions. In New perspectives on games and interaction, texts in logic and games (Vol. 4, pp. 9–31). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Baltag, A., & Smets, S. (2008b). A qualitative theory of dynamic interactive belief revision. In Proceedings of the 7th conference on LOFT, texts in logic and games (Vol. 3, pp. 13–60). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Bok, S. (1978). Lying: Moral Choice in Public and Private Life. New York: Random House.

Conitzer, V., Lang, J., & Xia, L. (2009). How hard is it to control sequential elections via the agenda? In Proceedings of the 21st IJCAI (pp. 103–108). San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

d’Agostino, G., & Lenzi, G. (2008). A note on bisimulation quantifiers and fixed points over transitive frames. Journal of Logic and Computation, 18(4), 601–614.

de Bruin, L., & Newen, A. (2013). The developmental paradox of false belief understanding: A dual-system solution. Synthese. doi:10.1007/S11229-012-0127-6.

Dégremont, C., Kurzen, L., & Szymanik, J. (2013). On the tractability of comparing informational structures. Synthese. doi:10.1007/S11229-012-0215-7.

Frankfurt, H. G. (2005). On bullshit. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gerbrandy, J. D., & Groeneveld, W. (1997). Reasoning about information change. Journal of Logic, Language, and Information, 6, 147–169.

Gneezy, U. (2005). Deception: The role of consequences. American Economic Review, 95(1), 384–394.

Grimm, J. L. K., & Grimm, W. K. (1812) Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Vol. 1). Berlin: Reimer.

Grimm, J. L. K., & Grimm, W. K. (1814) Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Vol. 2). Berlin: Reimer.

Hales, J. (2011). Refinement quantifiers for logics of belief and knowledge. Honours Thesis, University of Western Australia.

Halpern, J. Y., & Moses, Y. (1992). A guide to completeness and complexity for modal logics of knowledge and belief. Artificial Intelligence, 54, 319–379.

Hintikka, J. (1962). Knowledge and belief. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Hollebrandse, B., van Hout, A. & Hendriks, P. (2013). First and second-order false-belief reasoning: Does language support reasoning about the beliefs of others? Synthese. doi:10.1007/S11229-012-0169-9.

Icard, T. F., Pacuit, E., & Shoham, Y. (2010). Joint revision of beliefs and intention. In Proceedings of 12th KR. Menlo Park: AAAI Press.

Kartik, N., Ottaviani, M., & Squintani, F. (2006). Credulity, lies, and costly talk. Journal of Economic Theory, 134, 93–116.

Kooi, B. (2007). Expressivity and completeness for public update logics via reduction axioms. Journal of Applied Non-Classical Logics, 17(2), 231–254.

Kooi, B., & Renne, B. (2011). Arrow update logic. Review of Symbolic Logic, 4(4), 536–559.

Littlewood, J. E. (1953). A Mathematician’s Miscellany. London: Methuen and Company.

Liu, F., & Wang, Y. (2012). Reasoning about agent types and the hardest logic puzzle ever. Minds and Machines. doi:10.1007/s11023-012-9287-x.

Lutz, C. (2006). Complexity and succinctness of public announcement logic. In Proceedings of the 5th AAMAS (pp. 137–144).

Mahon, J. E. (2006). Two definitions of lying. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 22(2), 21–230.

Mahon, J. E. (2008). The definition of lying and deception. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2008/entries/lying-definition/.

Meyer, J.-J. Ch., & van der Hoek, W. (1995) Epistemic logic for AI and computer science. Cambridge tracts in theoretical computer science (Vol. 41). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Plaza, J. A. (1989). Logics of public communications. In Proceedings of the 4th ISMIS (pp. 201–216). Oak Ridge: Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Rodenhäuser, B. (2010). Intentions in interaction. In: Informal Proceedings of 7th LOFT.

Rott, H. (2003). Der Wert der Wahrheit. In M. Mayer (Ed.), Kulturen der Lüge (pp. 7–34). Böhlau-Verlag, Köln und Weimar.

Roy, O. (2009). A dynamic-epistemic hybrid logic for intentions and information changes in strategic games. Synthese, 171(2), 291–320.

Sakama, C. (2011). Dishonest reasoning by abduction. In Proceedings of 22nd IJCAI (pp. 1063–1064). IJCAI/AAAI.

Sakama, C. (2011). Formal definitions of lying. In: Proceedings of the 14th TRUST.

Sakama, C., Caminada, M., & Herzig, A. (2010). A logical account of lying. In Proceedings of the JELIA 2010, LNAI 6341 (pp. 286–299).

Siegler, F. A. (1966). Lying. American Philosophical Quarterly, 3, 128–136.

Steiner, D. (2006). A system for consistency preserving belief change. In Proceedings of the ESSLLI Workshop on Rationality and Knowledge (pp. 133–144).

Trivers, R. (2011). The Folly of Fools: The logic of deceit and self-deception in human life. New York: Basic Books.

van Benthem, J. (2007). Dynamic logic of belief revision. Journal of Applied Non-Classical Logics, 17(2), 129–155.

van der velden, J. H. (2011). Iedereen liegt maar ik niet. Bruna.

van Ditmarsch, H. (2005). Prolegomena to dynamic logic for belief revision. Synthese (Knowledge, Rationality & Action), 147, 229–275.

van Ditmarsch, H. (2008). Comments on ‘The logic of conditional doxastic actions’. In New perspectives on games and interaction texts in logic and games (Vol. 4, pp. 33–44). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

van Ditmarsch, H., de Lima, T., & Lorini, E. (2011). Intention change via local assignments. In Languages, Methodologies, and Development Tools for Multi-Agent Systems (Proceedings of 3rd LADS), LNAI 6822 (pp. 136–151). Heidelberg: Springer.

van Ditmarsch, H., van der Hoek, W., & Kooi, B. (2007). Dynamic Epistemic Logic, volume 337 of Synthese Library. Heidelberg: Springer.

van Ditmarsch, H., van Eijck, J., Sietsma, F., & Wang, Y. (2012). On the logic of lying. In Games, Actions and Social Software, LNCS 7010 (pp. 41–72). New York: Springer.

van Emde Boas, P., Groenendijk, J., & Stokhof, M. (1984). The Conway paradox: Its solution in an epistemic framework. In Truth, Interpretation and Information: Selected Papers from the Third Amsterdam Colloquium (pp. 159–182).

Acknowledgments

Hans van Ditmarsch is also affiliated to IMSc, Chennai, as associated researcher. I thank the anonymous reviewers of the journal Synthese for their comments, and for their persistence. I gratefully acknowledge comments from Alexandru Baltag, Jan van Eijck, Patrick Girard, Barteld Kooi, Fenrong Liu, Emiliano Lorini, Yoram Moses, Eric Pacuit, Rohit Parikh, Ramanujam, Hans Rott, Sonja Smets, Rineke Verbrugge, and Yanjing Wang. As my work on lying has a long history (from 2008 onward), I am concerned I may have forgotten to credit yet others, for which my apologies. As the editor of the special issue in which this contribution appears, Rineke had many valuable comments in addition to those by the reviewers, and was as always extremely encouraging. Emiliano spared me the embarrassment of including unsound axioms (and an incorrect action model) in the axiomatization of agent announcement logic, for which infinite thanks.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Ditmarsch, H. Dynamics of lying. Synthese 191, 745–777 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-013-0275-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-013-0275-3

, and

, and  . We then need two axioms only, namely

. We then need two axioms only, namely  . The axioms for plausible agent lying are more complex (they also involve conditional knowledge modalities).

. The axioms for plausible agent lying are more complex (they also involve conditional knowledge modalities).