Abstract

Severe Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) remains a major cause of death and disability afflicting mostly young adult males and elderly people, resulting in high economic costs to society. Therapeutic approaches focus on reducing the risk on secondary brain injury. Specific ethical issues pertaining in clinical testing of pharmacological neuroprotective agents in TBI include the emergency nature of the research, the incapacity of the patients to informed consent before inclusion, short therapeutic time windows, and a risk-benefit ratio based on concept that in relation to the severity of the trauma, significant adverse side effects may be acceptable for possible beneficial treatments. Randomized controlled phase III trials investigating the safety and efficacy of agents in TBI with promising benefit, conducted in acute emergency situations with short therapeutic time windows, should allow randomization under deferred consent or waiver of consent. Making progress in knowledge of treatment in acute neurological and other intensive care conditions is only possible if national regulations and legislations allow waiver of consent or deferred consent for clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Severe Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) remains a major cause of death and disability afflicting mostly young adult males and elderly people, resulting in high economic costs to society [1]. Road traffic accidents, domestic and work-related falls and assaults are the main causes of TBI in Europe. The fatality rate for severe TBI is about 30% and a significant disability in 35–40% in unselected series. The primary injury initiates a complex sequence of events resulting in secondary brain damage, which can be exacerbated by systemic insults, such as hypotension and hypoxia. Therapeutic approaches focus on reducing the risk on secondary brain injury. Pharmacological neuroprotective agents aim to limit secondary brain damage after the primary acute injury and aim to improve overall outcome. Various neuroprotective agents, mainly targeting specific pathophysiologic mechanisms, have been tested in TBI, but convincing benefit has not been shown [2]. These data signify an ethical imperative to develop and test new therapeutic strategies and neuroprotective pharmacological agents in the field of TBI.

The most important ethical issues pertaining to clinical pharmacological trials in severe TBI are:

-

1.

emergency nature of the research

-

2.

incapacity of the patients to consent

-

3.

short therapeutic time windows

-

4.

risk/benefit ratio based on the concept that in relation to the seriousness of the injury, significant adverse side effects may be acceptable for treatments with possible benefit.

The importance of implications of these issues is not fully recognized outside, and even within, the expert field of treatment of severe TBI.

Therapeutic trials to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pharmacological agents are subject to the ethical and juridical principles of Good Clinical Practice, national legislation and European and international regulations. The guiding ethical principles underlying these investigations of treatment are respect for autonomy of the subjects, protection against discomfort, harm, risk and exploitation and the prospect of benefit. The prospect of benefit is almost always complicated by the equipoise underpinning the statistical null hypothesis of pharmacological trials: the hope that an individual patient will benefit, but that this is not more certain than the chance of non benefit.

Countries in the European Union are amending legislation to comply with the European Union Directive 2001/20/EC [3]. In this European legislation, emergency research under deferred or waiver of consent is however not permitted. This will impede or even obviate emergency research phase III trials in TBI in the European countries [4–6].

The European Clinical trial Directive 2001/20/EC was originally aimed as a European-wide harmonization of the provisions concerning clinical pharmacological trials, with a focus at the facilitation of multi-national clinical research. Since the publication in 2001, several articles drew attention to the serious threat to the development of evidence-based critical care and emergency research within the European Union (EU) posed by the Directive 2001/20/EC which requires prior informed written consent before subjects can be recruited to clinical trials of medicinal products [7–19].

The Directive made no direct exception for emergency and critical care situations, and therefore threatened to prevent all emergency trials involving patients with acute catastrophic illness causing loss of decision-making capacity and facing (very) short therapeutic time windows, such as severe shock, circulatory arrest, acute myocardial infarction, severe stroke and other acute neurological conditions, and moderate and severe traumatic brain injury.

Implementation by all EU countries was required by May 2004. The wording of the Directive permitted some flexibility so that variations were expected that might impact on emergency research [20]. Lemaire et al. [9] have described the variations in national legislative responses to the Directive within Europe; they called on legislators to permit waivers of informed consent for emergency and critical care research, to clarify terms and definitions, and to remove the artificial distinction between interventional and observational research. Concerning practice in The Netherlands, the requirements as described in the Directive have been transposed into the revision of the Medical Research in Human Subjects Act (WMO) and Medicine law (WOG) [21]. The amended WMO will change the rules governing drugs studies in The Netherlands. There will be little, if any, change to non-drug research. The Dutch Parliament has accepted the amended WMO for the implementation (amended WMO) at November 22, 2005 and the revised Act became effective in The Netherlands on March 1, 2006.

The Directive was conceived in part to ensure that participants enrolled in research projects are given adequate information about the nature of the trials and the associated risks. Legislation to protect the interests of patients was necessary and timely. The research community welcomed most of the Articles in the Directive; they offer guidance and will help to maintain confidence in the probity of medical research. Unfortunately, however, neither those responsible for the Directive, nor many who drafted enabling legislation within Member States, considered the special problems relating to research in emergency nor critical care situations, where consent cannot be obtained from subjects and where the need for emergency treatment does not allow time for contact with relatives or other legal representatives. Moreover, in the United States, in 1996, the FDA had published a waiver of informed consent for certain types of emergency and critical care research after earlier strict provisions had brought to a halt important progress in some critical clinical situations.

This shortcoming and the variable response within European Member States to the requirements of the Directive, prompted an expert meeting to be convened in Vienna, Austria on 30 May 2005 (‘Vienna Initiative to save European Research’ [VISEAR]). A final report was presented in December 2005 and full reports appeared in the Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift in 2006. The initiative to the meeting was supported by the Department for Ethics in Medical Research of the Vienna Medical University, in cooperation with the European Forum for Good Clinical Practice (EFGCP), the European Clinical Research Infrastructures Network (ECRIN), and the Vienna School of Clinical Research. One of the six working groups aimed at ‘clinical trials including patients who are not able to consent; the concept of individual direct benefit from research and informed consent in case of the temporarily incapacitated patient’ Their recommendations were published in 2006 [6].

Consent Procedures

Informed consent in TBI victims can, due to the severity of the brain injury, never be obtained from the patients. Proxies or an independent physician must give consent for inclusion in research, or consent must be deferred or waived. Most ethical committees in European countries consider consent by legal representatives (proxy consent) valid. The moral basis for proxy consent is restricted to the substituted judgment about the inclusion into the trial. The proxy is supposed to act as the patient, if competent, would have decided. The question remains if the patient wants to be represented by relatives for inclusion in a trial. Roupie et al. [22] found that only 40.6% of 1,089 patients would want their spouse/partner to be their surrogate, 28% want to be represented by the physician in charge of their care.

Coppolino and Ackerson [23] concluded that surrogate decision makers for critical care research resulted in false-positive consent rates in up to 20%. In the study by Sulmasy et al. [24], agreement between patients and proxies varied between 57% and 81%, depending on whether previous discussions had taken place on similar situations. It is very unlikely that such existential discussions occur frequently in the target population prone to TBI (young adult males), resulting in lack of evidence as to what their relative would have wanted in case of severe TBI. Most proxies seem to make decisions in emergency situations based on what they hope that will happen (survival of the patient), rather than what is likely to happen (possible death or [severe] disability); this will bias decision-making towards possible therapeutic benefit, however small the chance will be [12].

In some European countries consent for randomization may be given by an independent physician. Different perceptives on consent by a physician are reflected in conflicting reports. In one study, 84% of patients with myocardial infarction felt that the physician could independently decide on inclusion, if the patient was unable to consent for himself [25]. In the field of neonatology only 11% of parents believe that physicians should decide regarding research participation [26].

With deferred (proxy) consent patients are included into the research without prior consent. After inclusion, the patient (deferred consent) or his/her representatives (deferred proxy consent) should be informed as soon as possible and subsequent informed consent should be requested.

With waiver of consent, all consent is waived. Emergency research without prior consent (deferred consent or waiver of consent) can morally be accepted on the principles of fairness, justice and beneficence [27].

As severe TBI mostly occur outside the domestic situation (road traffic accidents), proxies are rarely available during the first hours after TBI [28]. This prompted investigators to use deferred (proxy) consent and waiver of consent in emergency research facing very short therapeutic time windows. In the National Acute Brain Injury Study: Hypothermia (NABIS-H) resulted the adoption of waiver of consent in a higher enrolment and reduced the time between injury and treatment by approximately 45 min [27]. In this study, relatives of only 11 out of 113 patients arrived within 6 h of the injury. In a septic shock trial the investigators could not contact the proxies within the inclusion time in 74% of the cases, and these were included under waiver of consent [19]. In the CRASH trial, mean time to randomization was significantly longer in those hospitals where consent was required compared with those it was not (4.4 h [SE = 0.21] vs. 3.2 h [SE = 0.16]), the difference in the mean time to randomization was 1.2 h [95% CI 0.7 to 1.8 h] [29]. In our series in the dexanabinol trial only 174 out of 6,303 (2.7%) were excluded for reason that proxy consent could not be obtained within 6 h after injury [30].

Even when proxies are available, many do not know what the patient’s wishes are [31]. Surrogate decision makers for critical-care research resulted in false-positive consent rates of 16–20.3% [23]. The emotional nature of an emergency situation limited the reliability of proxy consent for clinical research [26, 31, 32]. Only 48% of 79 representatives of European Brain Injury Consortium (EBIC) associated neuro-trauma centers in 19 European countries feel that relatives can make a balanced decision in an emergency situation, 72% believed that a consent procedure forms a significant factor causing decrease in enrolment rate in a TBI study, and 83% believed that prior consent is a significant factor causing delay in initiation of study treatment [12]. Under emergency circumstances, proxy consent does not seem to secure proper patient/subject protection. To our experience the validity of informed consent and proxy consent given in an emergency situation is at least troubling. When consent for clinical research is sought during an emergency situation, comprehension is generally less than optimal [33–35]. A small minority realized that pharmacological trials are designed to assess not only efficacy but safety as well [36]. One study searching for public views on emergency exception to informed consent found that most (88%) of 530 people believed that research subjects should be informed prior to being enrolled, while 49% believed enrolling patients without prior consent in an emergency situation would be acceptable and 70% (369) would not object to being entered into such a study without providing prospective informed consent [37]. In another study 11 of 12 stroke patients stated that, if the patient of family was not able to consent, then the treating physician should make the decision for inclusion in an emergency trial [38].

The requirement for all patients to give written informed (proxy) consent before enrolment can result in major selection biases, such that registry patients were not representative of the typical patient [39].

The Emergency Nature of Research in TBI

Traumatic Brain Injury is by definition an acute condition. The emergency nature of pharmacological research in TBI is reflected by the fact that experimental and clinical studies have shown that patho-physiological cascades are initiated within minutes to hours following primary injury. Time windows for treatment modalities are therefore considered to be short. Experimental studies have shown the efficacy of many neuroprotective agents, if these were administered before, or within 15 min after injury; others have shown a window of efficacy of 3–6 h.

In the most recent international pharmacological trial in TBI, a phase III randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial investigating the efficacy and safety of a single dose Dexanabinol [40], the experimental data have consistently shown better protection the sooner the agent is administered after TBI [41]. In the animal model for TBI, this agent given up to 3 h after TBI was protective against breakdown of the blood–brain barrier and reduced formation of edema and resulted in less severe neurological symptoms [42]. Administered between 4 h and 6 h after injury, no significant reduction of cerebral edema was noticed, nevertheless neurological symptoms improved. Based on these findings, it may be concluded that in the experimental model the patho-physiologic endpoint can be determined at 3 h. If this time window also form the clinical therapeutic border in patients with severe TBI remains however uncertain. Time windows as applied to clinical trials in TBI have rarely been based on experimental evidence, but were rather determined by organizational and logistical considerations as to the time window within which investigators expected that a considerable number of patients could be enrolled. This was also the case in the recent Dexanabinol trial. One of the inclusion criteria in this trial was ‘sustained TBI within the past 6 h [40] Informed consent could, seen the severity of the brain injury, not be obtained from the patients. Proxy consent was accepted in all participating countries. Deferred patient or proxy consent was only allowed in Australia, Austria, Finland, France and Germany and consent by an independent physician was allowed in Israel, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom. In all cases of deferred consent, subsequent written assent by patient or proxy was obtained.

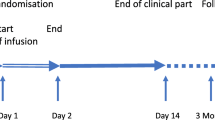

As coordinating quality control and assurance center for this trial, we had the opportunity to study time windows in more detail [43]. We defined for this analysis four different time windows:

-

1.

the time between injury and admission in a neuro-trauma center;

-

2.

the time between admission in a neuro-trauma center and first head CT scan;

-

3.

the time between the first head CT scan and proxy consent for inclusion in the trial;

-

4.

the time between proxy consent and study drug administration.

For analysis of these four time windows we selected 631 patients. The only selection criterion was that the study drug was administered after written proxy consent. Patients included in the trial under deferred consent were excluded from our analysis. Furthermore, we only included patients from Europe and Israel, excluding patients from Australia and the United States for other reasons [44]. The time between injury and admission at the neuro-trauma center was for all selected patients between 1 h, 16 h and 2.35 h (Table 1, Fig. 1). 501 (79.4%) patients were directly admitted to the neuro-trauma center, 130 cases (20.6%) concerns secondary referrals. In all patients the window between admission and the first diagnostic CT scan remains within 1 h. With exception of France, in all countries the median time between injury and completion of the CT scan remained within the 3 h (Table 1). The longest time window was found between the first diagnostic CT scan and obtaining the required proxy consent (between 1.71 h and 2.74 h). The median time between injury and obtained proxy consent was between 3.75 h and 5.00 h (IQR 2.75–5.38 h) (Table 1). After proxy consent was given, almost all patients subsequently received the study drug within one hour (Table 1, Fig. 1). In 85.3% of all cases the time between injury and study drug administration was longer than 4 h, in 60% of the cases even longer than 5 h.

Time between injury and admission neurotrauma center, time between admission and first CT scan, time between first CT scan and informed consent for inclusion in trial and time between consent and start study drug admission (from Ref. 43)

Dexanabinol was one of the promising new pharmaceuticals in the treatment of TBI, but it shown to be safe but not effective in the treatment of severe TBI [40]. Nevertheless, one can conclude that chances of efficacy increase if treatment is provided earlier. Fact is that in almost all of the studied cases the time between injury and completion of the primary diagnostic CT scan remains within 3 h post injury, which is shown to be the therapeutic time window in the animal model. In 60% of the cases the time between injury and study drug administration was however longer than 5 h, and in 85.3% of all cases longer than 4 h (Fig. 1). Our data provide the empirical proof for considering deferred consent or waiver of consent in trials with a very short therapeutic time window.

Risk-Benefit Ratio

To my opinion the balance between risk and benefit should be the guiding principle in emergency research in severe TBI. This also applies to the nature and the type of consent procedures. The ethical principle of respect for the autonomy of the patient underpinning the informed consent procedures is not valid for acutely incapacitated patients as TBI victims. Significant concerns has been raised on the validity and ethics of proxy consent in acute emergency situations, and the required written consent cause a significant delay in treatment initiation, as we have shown with our analysis of the time windows. The possible therapeutic benefit, as has been shown in experimental models, form the moral justification for randomizing patients under deferred consent or waiver of consent within a sufficient period of time. The risks should however be acceptable in relation to the severity of the disease or injury. For trials under deferred consent or waiver of consent in acute emergency situations we would constrain the institution of an independent safety committee, under the auspices of regulatory authorities. The obligation to such a committee is based on the experience of a dramatically harmful outcome in some trials under waiver of consent in other fields of medicine [45, 46].

Conclusions

Specific ethical issues pertaining in clinical testing of pharmacological neuroprotective agents in TBI include the emergency nature of the research, the incapacity of the patients to informed consent before inclusion, short therapeutic time windows, and a risk-benefit ratio based on concept that in relation to the severity of the trauma, significant adverse side effects may be acceptable for treatments with possible benefit.

Time windows as applied to randomized controlled clinical trials in TBI have rarely been based on experimental evidence, but were rather determined by organizational and logistical considerations as to a time window within which investigators expected that a considerable number of patients could be enrolled [12]. The main determinant is now formed by the informed (proxy) consent procedures, as also has been compelled in the new European Union Directive 2001/20/EC [3, 6]. These requirements assume that relatives are available in emergency situations, and that these relatives can be fully informed and given sufficient time to make a balanced decision in a relatively short time period. The conflict between the desire for early initiation of experimental treatment versus the time required for following consent procedures and the conflict between the desire for following consent procedures requiring prior consent and the doubts about the validity of proxy consent in acute situations are the most problematic aspects of emergency research in TBI.

Clinical research in emergency situations without prospective informed or proxy consent is ethically challenging. Severe TBI is without doubt an emergent and life-threatening condition and existing therapy is unsatisfactory seen the high morbidity and mortality in a mostly young group of patients. This should qualify severe TBI for emergency exception form informed consent for randomized clinical controlled trials with pharmacological agents with promising therapeutic benefit facing short therapeutic time windows. Randomized controlled investigations are necessary to determine the safety and effectiveness of new developed agents in these conditions. We have proved that the requirement of previous written proxy consent causes a significant delay till study drug administration in a trial with a neuroprotective agent in TBI. With waiver of consent or deferred (proxy) consent the first dose of the experimental drug can be administered directly after completion of the first diagnostic CT scan, which is very close to the experimental therapeutic time window. Randomized controlled phase III trials investigating the safety and efficacy of agents with promising benefit, conducted in acute emergency situations with short therapeutic time windows, should allow randomization under deferred (proxy) consent or waiver of consent. Making progress in knowledge of treatment in acute neurological and other intensive care conditions is only possible if national regulations and legislations allow waiver of consent or deferred (proxy) consent for clinical trials [15]. As two of us have said before: ‘treat first, ask later’ seems ethically defendable in acute care research [4].

References

McGarry, L. J., Thompson, D., Millham, F. H., Cowell, L., Snyder, P. J., Lenderking, W. R., & Weinstein, M. C. (2002). Outcomes and costs of acute treatment of traumatic brain injury. Journal of Trauma, 53, 1152–1159.

Maas, A. I. R., Steyerberg, E. W., & Murray, G. D. (1999). Why have recent trials of neuroprotective agents in head injury failed to show convincing efficacy? A pragmatic analysis and theoretical considerations. Neurosurgery, 44, 1286–1298.

European Union (2001) Directive 2001/20/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 4 april 2001 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States relating to the implementation of good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products for human use. Oficial Journal of the European Community L 121/34.

Kompanje, E. J. O., & Maas, A. I. R. (2004). ‘Treat first, ask later?’ Emergency research in acute neurology and neurotraumatology in the European Union. Intensive Care Medicine, 30, 168–169.

Silverman, H. J., Druml, C., Lemaire, F., & Nelson, R. (2004). The European Union directive and the protection of incapacitated subjects in research: An ethical analysis. Intensive Care Medicine, 30, 1723–1729.

Liddell, K., Chamberlain, D., Menon, D. K., Bion, J., Kompanje, E. J. O., Lemaire, F., Druml, C., Vrhovac, B., Widermann, C. J., & Sterz, F. (2006). The European clinical trial directive revisited: The VISEAR recommendations. Resuscitation, 69, 9–14.

Visser, H. K. A. (2001). Non-therapeutic research in the EU in adults incapable of giving consent? The Lancet, 357, 818–819.

Baeyens, A. J. (2002). Implementation of the clinical trials directive: Pitfalls and benefits. European Journal of Health Law, 9, 31–47.

Lemaire, F., Bion, J., Blanco, J., Damas, P., Druml, C.,& Falke, K. L. (2005). The European Union directive on clinical research: Present status of implementation in EU member states’ legislation with regard to the incompetent patient. Intensive Care Medicine, 31, 476–479.

Stertz, F., Singer, E. A., Böttiger, B., Chamberlain, D., Baskett, P., Bossaert, L., & Steen, P. (2002). A serious threat to evidence based resuscitation within the European Union. Resuscitation, 53, 237–238.

Kompanje, E. J. O., Maas, A. I. R., & Dippel, D. W. J. (2003). Klinisch geneesmiddelenonderzoek bij acuut beslissingsonbekwame patiënten in de neurologie en de neurochirurgie; implicaties van nieuwe Europese regelgeving. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde, 147, 1585–1589.

Kompanje, E. J. O., Maas, A. I. R., Hilhorst, M. T., Slieker, F. J. A., & Teasdale, G. M. (2005). Ethical considerations on consent procedures for emergency research in severe and moderate traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochirurgica, 147, 633–640.

Singer, E. A., & Druml, C. (2005). Collateral damage or apocalypse now for European academic research. Intensive Care Medicine, 31, 271.

Lemaire, F. J. P. (2003). A European directive for clinical research. Intensive Care Medicine, 29, 1818–1820.

Lemaire, F. (2005). Waiving consent for emergency research. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 35, 287–289.

Druml, C. (2004). Informed consent of incapable (ICU) patients in Europe: Existing laws and the EU directive. Current Opinion Critical Care, 10, 570–573.

Truog, R. D. (2005). Will ethical requirements bring critical care research to a halt? Intensive Care Medicine, 31, 338–344.

Klepsted, P., & Dale, O. (2006). Further restrictions for ICU research. Intensive Care Medicine, 32, 175.

Annane, D., Outlin, H., Fisch, C., & Bellissant, E. (2004). The effect of waiving consent on enrolment in a sepsis trial. Intensive Care Medicine, 30, 632–637.

Larsson, A., & Tønnesen, E. (2006). ICU research in Denmark: Difficult but possible. Intensive Care Medicine, 32, 934.

The Working Party for Implementation of Directive 2001/20/EC (2005). Clinical Research with medicinal products in the Netherlands. Ministry of Welfare and Sport.

Roupie, E., Santin, A., Boulme, R., Wartel, J. S., Lepage, E., Lemaire, F., Lejonc, J. L., & Montagne, O. (2000). Patients preferences concerning medical information and surrogacy: Results of a prospective study in a French emergency department. Intensive Care Medicine, 26, 52–56.

Coppolino, M., & Ackerson, L. (2001). Do surrogate decision makers provide accurate consent for intensive care research? Chest, 119, 603–612.

Sulmasy, D. P., Haller, K., & Terry, P. B. (1994). More talk, less paper: Predicting the accuracy of substituted judgments. American Journal of Medicine, 96, 432–438.

Ågård, A., Hermerén, G., & Herlitz, J. (2001). Patients experiences of intervention trials on the treatment of myocardial infarction: Is it time to adjust the informed consent procedure to the patients capacity? Heart, 86, 632–637.

Mason, S. A., & Allmark, P. J. (2000). Obtaining informed consent to neonatal randomised controlled trials: Interviews with parents and clinicians in the Euricon study. The Lancet, 356, 2045–2051.

Clifton, G. L., Knudson, P., & McDonald, M. (2002). Waiver of consent in studies of acute brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 19, 1121–1126.

Wright, D. W., Lancaster, R. T., & Lowery, D. W. (2001). Necessary time to achive next of kin proxy consent for acutely injured altered status patients. Academic Emergency Medicine, 8, 419–420.

CRASH trial management group. (2004). Research in emergency situations: With or without relatives consent. Emergency Medicine Journal, 21, 703.

Luce, J. M. (2003). Is the concept of informed consent applicable to clinical research involving critically ill patients? Critical Care Medicine, 31(Suppl.), S153–S160.

Hsieh, M., Dailey, M. W., & Callaway, C. W. (2001). Surrogate consent by family members for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest research. Academic Emergency Medicine, 8, 851–853.

Bigatello, L. M., George, E., & Hurford, W. E. (2003). Ethical considerations for research in critically ill patients. Critical Care Medicine, 31, S178–S181.

Cuttini, M. (2000). Proxy informed consent in pediatric research: A review. Early Human Development, 60, 89–100.

Sugarman, J. (2000). Is the emperor really wearing new clothes? Informed consent for acute coronary syndromes. American Heart Journal, 140, 2–3.

Williams, B. F., French, J. K., & White, H. D. (2003). Informed consent during the clinical emergency of acute myocardial infarction (HERO-2 consent substudy): A prospective observational study. The Lancet, 361, 918–922.

Harth, S. C., & Thong, Y. H. (1995). Parental perceptions and attitudes about informed consent in clinical research involving children. Social Science and Medicine, 40, 1573–1577.

McClure, K. B., Delorio, N. M., Gunnels, M. D., Ochsner, M. J., Biros, M. H., & Schmidt, T. A. (2003). Attitudes of emergency department patients and visitors regarding emergency exception from informed consent in resuscitation research, community consultation and public notification. Academic Emergency Medicine, 10, 352–359.

Blixen, C. E., & Agich, G. J. (2005). Stroke patients preferences and values about emergency research. Journal of Medical Ethics, 31, 608–661.

Tu, J. V., Willison, D. J., Silver, F. L., Fang, J., Richards, J. A., Laupacis, A., & Kapral, M. K. (2004). Impracticability of informed consent in the registry of the Canadian stroke network. New England Journal of Medicine, 350, 1414–1421.

Maas, A. I. R., Murray, G., Henney, H., Kassem, N., Legrand, V., Mangelus, M., Muizelaar, J. P., Stocchetti, N., Knoller, N, on behalf of the Pharmos TBI Investigators. (2006). Efficacy and safety of dexanabinol in sever traumatic brain injury: Results of a phase III randomized placebo controlled clinical trial. The Lancet-Neurology, 5, 38–45.

Hoff, J. T. (1986). Cerebral protection. Journal of Neurosurgery, 65, 579–591.

Shohami, E. (1995). Long-term effect of HU-211, a novel competitive NMDA antagonist, on motor and memory functions after closed head injury in the rat. Brain Research, 674, 55–56.

Kompanje, E. J. O., Maas, A. I. R., Slieker, F. J. A., & Stocchetti, N. (2007). Ethical implications of time frames in a randomized controlled trial in severe traumatic brain injury. Progress Brain Research, 161, 237–244.

Kompanje, E. J. O., & Maas, A. I. R. (2006). Is the Glasgow coma scale score protected health information? The effect of new United States regulations (HIPAA) on completion of screening logs in emergency research trials. Intensive Care Medicine, 32, 313–314.

Freeman, D. B. (2001). Safeguarding patients in clinical trials with high mortality rates. American Journal of Critical Care Medicine, 164, 190–192.

Lewis, R. J., Berry, D. A., Cryer, H., Fost, N., Krome, R., Washington, G. R., Houghton, J., Blue, J. W., Bechhofer, R., Cook, T., & Fisher, M. (2001). Monitoring a clinical trial conducted under the Food and Drug Administration regulations allowing a waiver of prospective informed consent: The Diaspirin cross-linked hemoglobin traumatic hemorrhagic shock efficacy trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 38, 397–404.

Kompanje, E. J. O., Maas, A. I. R., & Slieker, F. J. A. Deferred Consent or Waiver of Consent could be the answer. Time windows and ethical implications in a multi-center clinically controlled randomized Phase III trial in acute traumatic brain injury.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An earlier version of this paper was presented at The 7th International Conference on Bioethics on “The Ethics of Research in Emergency Medicine”, held on June 2, 2006, Warsaw, Poland.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kompanje, E.J.O. ‘No Time to be Lost!’ . Sci Eng Ethics 13, 371–381 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-007-9027-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-007-9027-4