Abstract

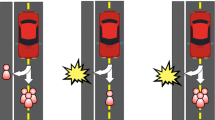

The recent progress in the development of autonomous cars has seen ethical questions come to the forefront. In particular, life and death decisions regarding the behavior of self-driving cars in trolley dilemma situations are attracting widespread interest in the recent debate. In this essay we want to ask whether we should implement a mandatory ethics setting (MES) for the whole of society or, whether every driver should have the choice to select his own personal ethics setting (PES). While the consensus view seems to be that people would not be willing to use an automated car that might sacrifice themselves in a dilemma situation, we will defend the somewhat contra-intuitive claim that this would be nevertheless in their best interest. The reason is, simply put, that a PES regime would most likely result in a prisoner’s dilemma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Henceforth, we will use the terms autonomous car, robot car and self-driving car interchangeably.

This is according to the data of the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. Note that the traffic-related death rate per 100,000 inhabitants is lower for first world countries due to safer (newer) technology, functioning regulation and enforcement of traffic laws.

We emphasize the normative point here, since there might be other perspectives from which the introduction of autonomous cars seems to pose a problem. People who enjoy having a steering wheel in their hand might fear, for instance, that autonomous cars will prove so much safer than regular cars that Elon Musk’s prediction comes true and the government might outlaw non-autonomous cars (Hof 2015).

One could argue that the manufactures could come together and agree on industry standards. There are two things to say to this. First, industry-wide standards are pretty hard to achieve in a globalized world with important car manufacturers all over the globe. Second, it is especially difficult if the industry standards do not reflect the preferences of consumers.

In this case, the expected value equals the expected number of deaths.

Unfortunately, we cannot debate the various ways in which such a maxim could be implemented. Although this maxim, on the face of it, seems quite simple, the implementation will surely raise many morally relevant follow-up questions. For instance, how should we weight lives? Should one person count equally regardless of, say, their age? Furthermore, who should count as ‘all people affected’—should this include just motorized participants in traffic or should this also include pedestrians?

However, note that our approach is contractarian by nature.

It should be noted, though, that the data just weekly confirms our argument. The reason is that there is a difference between what an individual deems as the right course of conduct and whether she wants that particular course of action to become a law that is applied to everyone.

An interesting question that arises from this line of argument would be whether a MES would incentivize people to car-share to minimize their risk of being targeted. The answer to that depends on many variables, for instance, to what degree people value time alone. From an ecological perspective, an incentive to carpool would surely not be a bad thing. Furthermore, more carpooling or the use of public transportation would mean less traffic, and less traffic might decrease the possibility of accidents. On the other hand, people could choose to pay people to accompany them in their cars to increase their safety. While this is not impossible, it seems highly unlikely to play a role.

For that reason we are also highly skeptical of Millar’s suggestion to apply ethical norms from medicine and bioethics to the case of autonomous cars.

We want to express our gratitude towards two anonymous reviewers who brought this point to our attention.

References

Becker, J., Colas, M. A., Nordbruch, S., Fausten, M. (2014). Bosch’s vision and roadmap toward fully autonomous driving. In G. Meyer & S. Beiker (Eds.), Road vehicle automation (pp. 49–59). Lecture Notes in Mobility. Springer International Publishing.

Blanco, M., Atwood, J., Russell, S., Trimble, T., McClafferty, J., & Perez, M. (2016). Automated vehicle crash rate comparison using naturalistic data. Virginia Tech Transportation Institute.

Bonnefon, J., Shariff, A., Rahwan, I. (2015). Autonomous vehicles need experimental ethics: Are we ready for utilitarian cars? CoRR, arXiv:1510.03346. Accessed February 2016.

Brennan, G., & Buchanan, J. (1985). The reason of rules: Constitutional political economy. Indianapolis: Cambridge University Press.

Coelingh, E., & Solyom, S. (2012). All aboard the robotic train. Ieee Spectrum 49.

Davies, A. (2015). Google’s Plan to eliminate human driving in 5 years. Wired. http://www.wired.com/2015/05/google-wants-eliminate-human-driving-5-years/. Accessed February 2016.

Donaldson, T., & Dunfee, T. (1999). The ties that bind: A social contract approach to business ethics. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

Fagnant, D., & Kockelman, K. (2013). Preparing a nation for autonomous vehicles. Eno Center of Transportation. https://www.enotrans.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/AV-paper.pdf. Accessed February 2016.

Foot, P. (1967). The problem of abortion and the doctrine of the double effect in virtues and vices. Oxford Review, 5, 5–15.

Gao, P., Hensley, R., & Zielke, A. (2014). A road map to the future for the auto industry. McKinsey Quarterly, Oct.

Gaus, G. (2005). Should philosophers ‘apply ethics’? Think, 3(09), 63–68.

Goodall, N. (2013). Ethical decision making during automated vehicle crashes. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2424, 58–65.

Goodall, N. (2014). Machine ethics and automated vehicles. In Road vehicle automation (pp. 93–102). Springer International Publishing.

Harris, M. (2015). Documents confirm Apple is building self-driving car. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/aug/14/apple-self-driving-car-project-titan-sooner-than-expected. Accessed February 2016.

Hevelke, A., & Nida-Rümelin, J. (2014). Responsibility for crashes of autonomous vehicles: An ethical analysis. Science and Engineering Ethics, 21(3), 619–630.

Hof, R. (2015). Tesla’s Elon Musk thinks cars you can actually drive will be outlawed eventually. Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/sites/roberthof/2015/03/17/elon-musk-eventually-cars\-you-can-actually-drive-may-be-outlawed/. Accessed February 2016.

Hongo, J. (2015). RoboCab: Driverless taxi experiment to start in Japan. Wall Street Journal. http://blogs.wsj.com/japanrealtime/2015/10/01/robocab-driverless-taxi-experiment-to-start-in-japan/. Accessed February 2016.

Huebner, B., & Hauser, M. D. (2011). Moral judgments about altruistic self-sacrifice: When philosophical and folk intuitions clash. Philosophical Psychology, 24(1), 73–94.

IEEE. (2012). This lane is my lane, that lane is your lane. http://www.ieee.org/about/news/2012/5september_2_2012.html. Accessed February 2016.

Kumfer, W., & Burgess, R. (2015). Investigation into the role of rational ethics in crashes of automated vehicles. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2489, 130–136.

Lin, P. (2013). The ethics of autonomous cars, The Atlantic. http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/10/the-ethics-of-autonomous-cars/280360/. Accessed February 2016.

Lin, P. (2014a). What if your autonomous car keeps routing you past Krispy Kreme? The Atlantic. http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/01/what-if-your-autonomous-car-keeps-routing-you-past-krispy-kreme/283221/. Accessed February 2016.

Lin, P. (2014b). Here’s a terrible idea: Robot cars with adjustable ethics settings. WIRED. http://www.wired.com/2014/08/heres-a-terrible-idea-robot-cars-with-adjustable-ethics-settings/. Accessed February 2016.

Marcus, G. (2012). Moral machines. The New Yorker Blogs. http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/newsdesk/2012/11/google-driverless-car-morality.html. Accessed February 2016.

Marshall, S., & Niles, J. (2014). Synergies between vehicle automation, telematics connectivity, and electric propulsion. In G. Meyer & S. Beiker (Eds.), Road vehicle automation. Berlin: Springer.

Mchuch, M. (2015). Tesla’s cars now drive themselves, Kinda. WIRED. http://www.wired.com/2015/10/tesla-self-driving-over-air-update-live/. Accessed February 2016.

Meyer, G., Dokic, J., & Müller, B. (2015). Elements of a European roadmap on smart systems for automated driving. In Gereon Meyer und Sven Beiker (Eds.), Road vehicle automation 2 (pp. 153–159). Springer International Publishing.

Millar, J. (2014a). Proxy prudence: Rethinking models of responsibility for semi-autonomous robots. Available at SSRN 2442273.

Millar, J. (2014b). An ethical dilemma: When robot cars must kill, who should pick the victim? Robohub.org. http://robohub.org/an-ethical-dilemma-when-robot-cars-must-kill-who-should-pick-the-victim. Accessed February 2016.

Millar, J. (2014c). You should have a say in your robot car’s code of ethics. WIRED. http://www.wired.com/2014/09/set-the-ethics-robot-car. Accessed April 2016.

Mladenovic, M. N., & McPherson, T. (2015). Engineering social justice into traffic control for self-driving vehicles? Science and Engineering Ethics. doi:10.1007/s11948-015-9690-9.

Murgia, M. (2015). First driverless pods to travel public roads arrive in the Netherlands. The Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/news/11879182/First-driverless-pods-to-travel-public-roads-arrive-in-the-Netherlands.html. Accessed February 2016.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2013). Preliminary statement of policy concerning automated vehicles. http://www.nhtsa.gov/staticfiles/rulemaking/pdf/Automated_Vehicles_Policy.pdf. Accessed February 2016.

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity (pp. 258–270). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Powers, T. M. (2006). Prospects for a Kantian machine. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 21(4), 46–51.

Powers, T. M. (2013). Prospects for a Smithian machine. In: Proceedings of the international association for computing and philosophy, College Park, MD.

Rawls, J. (1993). Political liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Robinson, J. (2014). Would you kill the fat man? Teaching Philosophy, 37, 449–451.

Sandberg, A., & Bradshaw, H. G. (2013). Autonomous vehicles, moral agency and moral proxyhood. In Beyond AI conference proceedings. Springer.

Schrank, D., Lomax, T., Eisele, B. (2011). TTIs 2011 urban mobility report, Texas Transportation Institute. http://d2dtl5nnlpfr0r.cloudfront.net/tti.tamu.edu/documents/mobility-report-2011-wappx.pdf. Accessed February 2016.

Shanker, R., Jonas, A., Devitt, S., Humphrey, A., Flannery, S., Greene, W., et al. (2013). Autonomous cars: Self-driving the new auto industry paradigm. Morgan Stanley Blue Paper, November.

Silberg, G., Wallace, R., Matuszak, G., Plessers, J., Brower, C., & Subramanian, D. (2012). Self-driving cars: The next revolution (pp. 10–15). KPMG and Center for Automotive Research.

Smith, B. W. (2014). A legal perspective on three misconceptions in vehicle automation. In G. Meyer & S. Beiker (Eds.), Road vehicle automation (pp. 85–91). Berlin: Springer International Publishing.

Spieser, K., Ballantyne, K., Treleaven, R., Frazzoli, E., Morton, D., & Pavone, M. (2014). Toward a systematic approach to the design and evaluation of automated mobility-on-demand systems: A case study in Singapore. In G. Meyer & S. Beiker (Eds.), Road vehicle automation. Berlin: Springer.

Thomson, J. J. (1976). Killing, letting die, and the trolley problem. The Monist, 59(2), 204–217.

Thomson, J. J. (1985). Double effect, triple effect and the trolley problem: Squaring the circle in looping cases. Yale Law Journal, 94(6), 1395–1415.

Torbert, R., & Herrschaft, B. (2013). Driving Miss Hazy: Will driverless cars decrease fossil fuel consumption? Rocky Mountain Institute. http://blog.rmi.org/blog_2013_01_25_Driving_Miss_Hazy_Driverless_Cars. Accessed February 2016.

World Health Organisation. (2011). Road traffic deaths: Data by country. WHO. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.A997. Accessed February 2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gogoll, J., Müller, J.F. Autonomous Cars: In Favor of a Mandatory Ethics Setting. Sci Eng Ethics 23, 681–700 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-016-9806-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-016-9806-x