Abstract

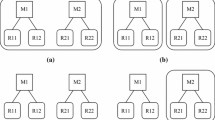

This article aims at studying the incentive for factoring in competing supply chains to examine the influences of the factoring decision in one supply chain on other chains. We consider multiple competing supply chains, each consisting of a manufacturer and a retailer. We firstly examine the issue under the special case of two supply chains, and then extend the model to multiple supply chains. The extended model is actually a bi-level non-cooperative game with multiple leaders and multiple followers, which we formulate as an Equilibrium Problem with Equilibrium Constraints. Numerical examples are presented to illustrate the rationality of the proposed model for the supply chains competition with financing choices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that the profit of the retailer is expressed as \(K^2\) in Eq. (7), which seems unreasonable considering the units of measurement of \(\pi _i\) and K. The main reason for that is that the inverse demand function in Sect. 3 is given by \(p_i=a-q_i-rq_j\), which is a simplified form commonly used in many researches, just like Ha et al. (2011). Even adopting a more generalized inverse demand function, i.e. \(p_i=a-bq_i-rq_j\), our analysis and the final conclusions of this work will not be affected since the two expressions are actually interchangeable. Readers are referred to McGuire and Staelin (1983) for more details.

References

Ai XZ, Chen J, Zhao HX, Tang XW (2012) Competition among supply chains: Implications of full returns policy. Int J Prod Econ 139:257–265

Amin-Naseri MR, Khojasteh MA (2015) Price competition between two leader-follower supply chains with risk-averse retailers under demand uncertainty. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 79:377–393

Barron EN (2013) Solution methods for matrix games. In: Game theory: an introduction (pp. 60-114). Wiley, Hoboken

Cachon GP, Kok AG (2010) Competing manufacturers in a retail supply chain: on contractual form and coordination. Manag Sci 56(3):571–589

Cai G, Chen X, Xiao Z (2014) The roles of bank and trade credits: theoretical analysis and empirical evidence. Prod Oper Manag 23(4):583–598

Chen Z, Tian C, Zhang D (2019) Supply chains competition with vertical and horizontal information sharing. Eur J Ind Eng 13(1):29–53

Demiguel V, Xu H (2009) A stochastic multiple-leader stackelberg model: analysis, computation, and application. Oper Res 57(5):1220–1235

Fletcher R, Leyffer S (2004) Solving mathematical program with complementarity constraints as nonlinear programs. Opt Method Softw 19(1):15–40

Gabriel SA, Leuthold FU (2010) Solving discretely-constrained MPEC problems with applications in electric power markets. Energy Econ 32(1):3–14

Guo L, Li T, Zhang HT (2014) Strategic information sharing in competing channels. Prod Oper Manag 23(10):1719–1731

Ha AY, Tong SL, Zhang HT (2011) Sharing demand information in competing supply chains with production diseconomies. Manag Sci 57(3):566–581

Hobbs B, Metzler C, Pang J (2000) Strategic gaming analysis for electric power systems: an MPEC Approach. IEEE Trans Power Syst 15(2):638–645

Hu X, Ralph D (2007) Using EPECs to model bilevel games in restructured electricity markets with locational prices. Oper Res 55(5):809–827

Kouvelis P, Zhao W (2012) Financing the newsvendor: supplier vs. bank and the structure of optimal trade credit contracts. Oper Res 60(3):566–580

Kouvelis P, Xu F (2018) A supply chain theory of factoring and reverse factoring. Working paper

Lekkakos SD, Serrano A (2016) Supply chain finance for small and medium sized enterprises: the case of reverse factoring. Int J Phys Distrib Log Manag 46(4):367–392

Li Y, Gu C (2018) Factoring policy with constant demand and limited capital. Int Trans Oper Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/itor.12514

Liu Z, Li KW, Li BY et al (2019) Impact of product-design strategies on the operations of a closed-loop supply chain. Transp Res Part E: Log Transp Rev 124:75–91

McGuire TW, Staelin R (1983) An industry equilibrium analysis of downstream vertical integration. Market Sci 2(2):161–191

Moon I, Sarmah SP, Saha S (2018) The impact of online sales on centralised and decentralised dual-channel supply chains. Eur J Ind Eng 12(1):67–92

Singh N, Vives X (1984) Price and quantity competition in a differentiated duopoly. Rand J Econ 15(4):546–554

Tanrisever F, Cetinay H, Reindorp M, Fransoo JC (2015) Reverse factoring for SME finance. Working Paper

Tsay AA, Agrawal N (2000) Channel dynamics under price and service competition. Manuf Serv Oper Manag 2(4):372–391

Tunca TI, Zhu W (2018) Buyer intermediation in supplier finance. Manag Sci 64(12):5631–5650

Van der Vliet K, Reindorp MJ, Fransoo JC (2015a) The price of reverse factoring: financing rates vs. payment delays. Eur J Oper Res 242(3):842–853

Van der Vliet K, Reindorp MJ, Fransoo JC (2015b) Improving service levels through reverse factoring. Working paper

Wuttke DA, Blome C, Heese HS, Protopappa-Sieke M (2016) Supply chain finance: optimal introduction and adoption decisions. Int J Prod Econ 178:72–81

Yang SA, Birge JR (2018) Trade credit, risk sharing, and inventory financing portfolios. Manag Sci 64(8):3667–3689

Yang L, Zhang Q, Ji JN (2017) Pricing and carbon emission reduction decisions in supply chains with vertical and horizontal cooperation. Int J Prod Econ 191(9):286–297

Yao J, Oren SS, Adler I (2007) Two-settlement electricity markets with price caps and cournot generation firms. Eur J Oper Res 181(3):1279–1296

Zhang D, Xu H, Wu Y (2010) A two stage stochastic equilibrium model for electricity markets with two way contracts. Math Methods Oper Res 71(1):1–45

Zheng XX, Li DF, Liu Z et al (2019a) Coordinating a closed-loop supply chain with fairness concerns through variable-weighted Shapley values. Transp Res Part E: Log Transp Rev 126:227–253

Zheng XX, Liu Z, Li KW et al (2019b) Cooperative game approaches to coordinating a three-echelon closed-loop supply chain with fairness concerns. Int J Prod Econ 212:92–110

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the editor and two anonymous referees for their very help and valuable suggestions that have helped significantly improve the quality of this paper. This research was funded by The National Social Science Fund of China (Grant NO. 19BGL259).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Proof of Proposition 1

According to the problem (5), it is easy to obtain:

-

(1)

If \(ar-2[(a-c)-K(4-r^2)]\ge 0\), the optimal reaction for manufacturer i can be expressed as

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rrr} w_i^{*(N,N)}(w^{(N,N)}_j)= \left\{ \begin{array}{lll} \frac{2(a+c)-r(a-w^{(N,N)}_j)}{4}, w^{(N,N)}_j\le \frac{ar-2[(a-c)-K(4-r^2)]}{r} \\ \frac{a(2-r)+rw^{(N,N)}_j-K(4-r^2)}{2}, w^{(N,N)}_j>\frac{ar-2[(a-c)-K(4-r^2)]}{r} \end{array} \right. \\ i,j=1,2, i\ne j \end{array} \end{aligned}$$If \(w^{(N,N)}_j\le \frac{ar-2[(a-c)-K(4-r^2)]}{r}\), we say manufacturer j adopts a “high wholesale price” strategy, otherwise, adopts a “low wholesale price” strategy. Consequently, the optimal decisions and pay-off matrix for the two competing manufacturers are showed in Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

\(\square \)

For every \(K\le \frac{2(a-c)}{(4 - r)(2+r)}\), it is easy to verify that \(K [(a - c) - K (2 + r)]-\frac{K(2-r)[(4+r)(a-c)-4K(2+r)]}{8-r^2}\ge 0\). Consequently, the two manufacturers have incentive to increase their wholesale prices to maximize the pay-offs. Hence, if \(ar-2[(a-c)-K(4-r^2)]\ge 0\), the equilibrium decisions for the two manufacturers are \(w^{(N,N)}_i=a-(2+r)K\), \(i=1,2\).

(2) If \(ar-2[(a-c)-K(4-r^2)]< 0\), the optimal reaction for manufacturer i is

Consequently the equilibrium decisions for the two manufacturers are \(w^{*(N,N)}_i=a-(2+r)K\), \(i=1,2\). Proposition 1 is proofed.

Specially, the proofs of Propositions 3 and 4 are similar to that of Proposition 1, and we omit it here.

Proof of Proposition 2

Based on the conclusions proposed in Proposition 1, the proposition can be easily obtained. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 5

Based on the conclusions proposed in Propositions 1, 2 and 4, the proposition can be obtained. \(\square \)

Proof of Theorem 1

-

(1)

According to Proposition 5, for every \(\eta \le \bar{\eta }\), \(\pi _1^{*(F,N)}\ge \pi _1^{*(N,N)} \) and \(\pi _1^{*(F,F)}\ge \pi _1^{*(N,F)}\). Consequently, the retailers prefer the strategy F to N. Hence, under the wholesale price only, the equilibrium financing strategies of the two supply chains depend only on the incentive of the manufacturers to adopt factoring.

-

(2)

Given the financing strategy of each supply chain as N, we can conclude that \(\varPi _1^{*(F,N)}\ge \varPi _1^{*(N,N)}\) and \(\varPi _2^{*(F,F)}\ge \varPi _2^{*(F,N)}\) for every \(\eta \le \bar{\eta }\) and \(K\le K_2\). Consequently, if the initiated financing arrangement is (N, N), manufacturer 1 has incentive to propose factoring finance, resulting in a new financing arrangement of (F, N). Furthermore, manufacturer 2’s unique response is F, which causes the pair of the strategies yields (F, F). The process can be summarized as \((N,N)\rightarrow (F,N)\) or \((N,F)\rightarrow (F,F)\). Hence, (F, F) is the unique equilibrium financing strategy for every \(\eta \le \bar{\eta }\) and \(K\le K_2\).

-

(3)

For every \(\eta \le \bar{\eta }\) and \(K_4\le K\le K_2\), \(\varPi _i^{*(F,F)}\le \varPi _i^{*(N,N)}\), hence (F, F) is the prison’s dilemma.

-

(4)

Similar to the above proofs, we can obtain the rest conclusions in Theorem 1.

\(\square \)

Proof of Theorem 2

The proof is similar to that of Theorem 1, therefore, we omit it here. \(\square \)

Proof of Theorem 3

By concavity and the maximum principle, for given \(w_i\), we know that \(q_i\) is a Nash equilibrium if and only if for each \(i = 1, 2,\ldots ,m\)

Thus, if \(q^*\) is a Nash equilibrium for the retailers, then by concatenating these inequalities, it follows easily that \(q^*\) must solve variational inequalities problem (16).

Conversely, for given w, if \(q^*\) solves variational inequalities problem (16), for each \(i = 1,2,\ldots ,m\), let q be the tuple whose j-th sub-vector is equal to \(q^*_j\) for \(j \not = i\) and \(q_i\) is an arbitrary element of the set \(R_+\). The variational inequalities problem (16) then becomes the above inequality. Consequently, Theorem 3 is proofed. \(\square \)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, D., Tian, C., Chen, Z. et al. Competition among supply chains: the choice of financing strategy. Oper Res Int J 22, 977–1000 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12351-020-00579-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12351-020-00579-1