Review:

Virtual Mirror and Beyond: The Psychological Basis for Avatar Embodiment via a Mirror

Yasuyuki Inoue and Michiteru Kitazaki

Toyohashi University of Technology

1-1 Hibarigaoka, Tempaku, Toyohashi, Aichi 441-8580, Japan

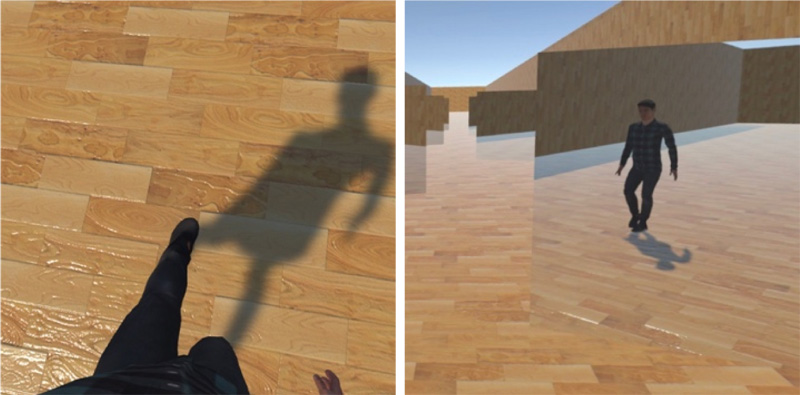

In virtual reality (VR), a virtual mirror is often used to display the VR avatar to the user for enhancing the embodiment. The reflected image of the synchronization of the virtual body with the user’s movement is expected to be recognized as the user’s own reflection. In addition to the visuo-motor synchrony, there are some mirror reflection factors that are probably involved in avatar embodiment. This paper reviews literature on the psychological studies that involve mirror-specific self-identification and embodied perception to clarify how the reflected image of the virtual body is embodied. Furthermore, subjective misconceptions about mirror reflections reported in naïve optics have also been reviewed to discuss the potential of virtual mirror displays to modulate avatar embodiment.

How virtual mirror enhances embodiment?

- [1] B. Spanlang, J. Normand, D. Borland, K. Kilteni, E. Giannopoulos, A. Pomés, M. González-Franco, D. Perez-Marcos, J. Arroyo-Palacios, X. N. Muncunill, and M. Slater, “How to Build an Embodiment Lab: Achieving Body Representation Illusions in Virtual Reality,” Frontiers in Robotics and AI, Vol.1, No.9, 2014.

- [2] M. González-Franco and C. T. Peck, “Avatar Embodiment. Towards a Standardized Questionnaire,” Frontiers in Robotics and AI, Vol.5, No.74, 2018.

- [3] K. Kilteni, R. Groten, and M. Slater, “The Sense of Embodiment in Virtual Reality,” Presence, Vol.21, Issue 4, pp. 373-387, 2012.

- [4] Y. Matsuda, J. Nakamura, T. Amemiya, Y. Ikei, and M. Kitazaki, “Enhancing Virtual Walking Sensation using Self-Avatar in First-person Perspective and Foot Vibrations,” Frontiers in Virtual Reality, Vol.2, 654088, 2021.

- [5] A. Boyle, “Mirror Self Recognition and Self Identification,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Vol.97, Issue 2, pp. 284-303, 2018.

- [6] A. E. Bigelow, “The correspondence between self- and image movement as a cue to self-recognition for young children,” J. of Genetic Psychology, Vol.139, Issue 1, pp. 11-26, 1981.

- [7] M. Miyazaki and K. Hiraki, “Delayed Intermodal Contingency Affects Young Children’s Recognition of Their Current Self,” Child Development, Vol.77, Issue 3, pp. 736-750, 2006.

- [8] R. W. Mitchell, “Kinesthetic-Visual Matching and the Self-Concept as Explanations of Mirror-Self-Recognition,” J. for the Theory of Social Behaviour, Vol.27, Issue 1, pp. 17-39, 1997.

- [9] M. A. J. Apps and M. Tsakiris, “The free-energy self: A predictive coding account of self-recognition,” Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, Vol.41, pp. 85-97, 2014.

- [10] E. Kokkinara and M. Slater, “Measuring the effects through time of the influence of visuomotor and visuotactile synchronous stimulation on a virtual body ownership illusion,” Perception, Vol.43, Issue 1, pp. 43-58, 2014.

- [11] M. González-Franco, D. Pérez-Marcos, B. Spanlang, and M. Slater, “The contribution of real-time mirror reflections of motor actions on virtual body ownership in an immersive virtual environment,” Proc. of 2010 IEEE Virtual Reality Conf. (VR 2010), pp. 111-114, 2010.

- [12] M. Slater, B. Spanlang, M. V. Sanchez-Vives, and O. Blanke, “First Person Experience of Body Transfer in Virtual Reality,” PLOS ONE, Vol.5, Issue 5, e10564, 2010.

- [13] H. H. Ehrsson, “The experimental induction of out-of-body experiences,” Science, Vol.317, Issue 5841, 1048, 2007.

- [14] B. Lenggenhager, T. Tadi, T. Metzinger, and O. Blanke, “Video ergo sum: manipulating bodily self-consciousness,” Science, Vol.317, Issue 5841, pp. 1096-1099, 2007.

- [15] A. Pomes and M. Slater, “Drift and ownership toward a distant virtual body,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, Vol.7, 908, 2013.

- [16] R. Kondo, M. Sugimoto, K. Minamizawa, T. Hoshi, M. Inami, and M. Kitazaki, “Illusory body ownership of an invisible body interpolated between virtual hands and feet via visual-motor synchronicity,” Scientific Reports, Vol.8, 7541, 2018.

- [17] A. Maravita, C. Spence, C. Sergent, and J. Driver, “Seeing Your Own Touched Hands in a Mirror Modulates Cross-Modal Interactions,” Psychological Science, Vol.13, Issue 4, pp. 350-355, 2002.

- [18] M. Bertamini, N. Berselli, C. Bode, R. Lawson, and L. T. Wong, “The rubber hand illusion in a mirror,” Consciousness and Cognition, Vol.20, Issue 4, pp. 1108-1119, 2011.

- [19] C. Preston, B. Kuper-Smith, and H. Ehrsson, “Owning the body in the mirror: The effect of visual perspective and mirror view on the full-body illusion,” Scientific Reports, Vol.5, 18345, 2015.

- [20] S. Yoshida, T. Tanikawa, S. Sakurai, M. Hirose, and T. Narumi, “Manipulation of an emotional experience by real-time deformed facial feedback,” Proc. of the 4th Augmented Human Int. Conf. (AH ’13), pp. 35-42, 2013.

- [21] D. Banakou, R. Groten, and M. Slater, “Illusory ownership of a virtual child body causes overestimation of object sizes and implicit attitude changes,” Proc. of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol.110, pp. 12846-12851, 2013.

- [22] M. Matsangidou, B. Otkhmezuri, C. S. Ang, M. Avraamides, G. Riva, A. Gaggioli, D. Iosif, and M. Karekla, ““Now I can see me” designing a multi-user virtual reality remote psychotherapy for body weight and shape concerns,” Human-Computer Interaction, doi: 10.1080/07370024.2020.1788945, 2020.

- [23] C. J. Croucher, M. Bertamini, and H. Hecht, “Naive optics: Understanding the geometry of mirror reflections,” J. of Experimental Psychology, Vol.28, No.3, pp. 546-562, 2002.

- [24] M. Bertamini, A. Spooner, and H. Hecht, “Naive optics: Predicting and perceiving reflections in mirrors,” J. of Experimental Psychology, Vol.29, No.5, pp. 982-1002, 2003.

- [25] R. Lawson and M. Bertamini, “Errors in Judging Information about Reflections in Mirrors,” Perception, Vol.35, Issue 9, pp. 1265-1288, 2006.

- [26] I. Bianchi and U. Savardi, “The Relationship Perceived between the Real Body and the Mirror Image,” Perception, Vol.37, Issue 5, pp. 666-687, 2008.

- [27] I. Bianchi and U. Savardi, “What fits into a mirror: naïve beliefs about the field of view,” J. of Experimental Psychology, Human Perception and Performance, Vol.38, No.5, pp. 1144-1158, 2012.

- [28] I. Pachoulakis and K. Kapetanakis, “Augmented reality platforms for virtual fitting rooms,” The Int. J. of Multimedia and Its Applications, Vol.4, No.4, doi: 10.5121/ijma.2012.4404, 2012.

- [29] A. Javornik, Y. Rogers, A. M. Moutinho, and R. Freeman, “Revealing the Shopper Experience of Using a “Magic Mirror” Augmented Reality Make-Up Application,” Proc. of the 2016 ACM Conf. on Designing Interactive Systems (DIS ’16), pp. 871-882, 2016.

- [30] T. Waltemate, I. Senna, F. Hülsmann, M. Rohde, S. Kopp, M. Ernst, and M. Botsch, “The impact of latency on perceptual judgments and motor performance in closed-loop interaction in virtual reality,” Proc. of the 22nd ACM Conf. on Virtual Reality Software and Technology (VRST ’16), pp. 27-35, 2016.

- [31] J. Lugrin, M. Landeck, and M. E. Latoschik, “Avatar embodiment realism and virtual fitness training,” Proc. of 2015 IEEE Virtual Reality (VR 2015), pp. 225-226, 2015.

- [32] L. M. Weber, D. M. Nilsen, G. Gillen, J. Yoon, and J. Stein, “Immersive Virtual Reality Mirror Therapy for Upper Limb Recovery After Stroke: A Pilot Study,” American J. of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Vol.98, No.9, pp. 783-788, 2019.

- [33] N. Yee and J. Bailenson, “The Proteus Effect: The Effect of Transformed Self-Representation on Behavior,” Human Communication Research, Vol.33, pp. 271-290, 2007.

- [34] V. Groom, J. Bailenson, and C. Nass, “The influence of racial embodiment on racial bias in immersive virtual environments,” Social Influence, Vol.4, Issue 3, pp. 231-248, 2009.

- [35] J. Fox, J. N. Bailenson, and L. Tricase, “The embodiment of sexualized virtual selves: The Proteus effect and experiences of self-objectification via avatars,” Computers in Human Behavior, Vol.29, Issue 3, pp. 930-938, 2013.

- [36] H. E. Hershfield, D. G. Goldstein, W. F. Sharpe, J. Fox, L. Yeykelis, L. L. Carstensen, and J. N. Bailenson, “Increasing Saving Behavior Through Age-Progressed Renderings of the Future Self,” J. of Marketing Research, Vol.48, pp. S23-S37, 2011.

- [37] L. Maister, M. Slater, M. V. Sanchez-Vives, and M. Tsakiris, “Changing bodies changes minds: owning another body affects social cognition,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol.19, Issue 1, pp. 6-12, 2015.

- [38] A. Krekhov, S. Cmentowski, and J. Krüger, “The Illusion of Animal Body Ownership and Its Potential for Virtual Reality Games,” Proc. of 2019 IEEE Conf. on Games (CoG), pp. 1-8, 2019.

- [39] V. Petkova, M. Khoshnevis, and H. H. Ehrsson, “The Perspective Matters! Multisensory Integration in Ego-Centric Reference Frames Determines Full-Body Ownership,” Frontiers in Psychology, Vol.2, 35, 2011.

- [40] M. Antonella and M. Slater, “The building blocks of the full-body ownership illusion,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, Vol.7, 83, 2013.

- [41] R. Kondo, Y. Tani, M. Sugimoto, M. Inami, and M. Kitazaki, “Scrambled body differentiates body part ownership from the full body illusion,” Scientific Reports, Vol.10, 5274, 2020.

- [42] P. Bourdin, I. Barberia, R. Oliva, and M. Slater, “A Virtual Out-of-Body Experience Reduces Fear of Death,” PLOS ONE, Vol.12, No.1, e0169343, 2017.

- [43] I. Bergström, K. Kilteni, and M. Slater, “First-Person Perspective Virtual Body Posture Influences Stress: A Virtual Reality Body Ownership Study,” PLOS ONE, Vol.11, No.2, e0148060, 2016.

- [44] G. G. Gallup, “Chimpanzees: Self-recognition,” Science, Vol.167, pp. 86-87, 1970.

- [45] J. R. Anderson and G. G. Gallup, “Which Primates Recognize Themselves in Mirrors?,” PLOS Biology, Vol.9, No.3, e1001024, 2011.

- [46] B. Amsterdam, “Mirror self-image reactions before age two,” Developmental Psychobiology, Vol.5, Issue 4, pp. 297-305, 1972.

- [47] M. Nielsen, T. Suddendorf, and V. Slaughter, “Mirror Self Recognition Beyond the Face,” Child Development, Vol.77, Issue 1, pp. 176-185, 2006.

- [48] T. Suddendorf, G. Simcock, and M. Nielsen, “Visual self-recognition in mirrors and live videos: Evidence for a developmental asynchrony,” Cognitive Development, Vol.22, Issue 2, pp. 185-196, 2007.

- [49] P. Rochat and D. Zahavi, “The uncanny mirror: A re-framing of mirror self-experience,” Consciousness and Cognition, Vol.20, pp. 204-213, 2011.

- [50] C. M. Heyes, “Reflections on self-recognition in primates,” Animal Behaviour, Vol.47, Issue 4, pp. 909-919, 1994.

- [51] U. Neisser, “The Roots of Self Knowledge: Perceiving Self, It, and Thou,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol.818, pp. 19-33, 1997.

- [52] D. J. Povinelli, K. R. Landau, and H. K. Perilloux, “Self-Recognition in Young Children Using Delayed versus Live Feedback: Evidence of a Developmental Asynchrony,” Child Development, Vol.67, No.4, pp. 1540-1554, 1996.

- [53] T. Suddendorf and D. L. Butler, “The nature of visual self-recognition,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol.17, Issue 3, pp. 121-127, 2013.

- [54] Y. Inoue, F. Kato, M. Y. Saraiji, C. Fernando, and S. Tachi, “Observation of mirror reflection and voluntary self-Touch enhance self-recognition for a telexistence robot,” Proc. of 2017 IEEE Virtual Reality (VR 2017), pp. 345-346, 2017.

- [55] J. P. Keenan, M. A. Wheeler, G. G. Gallup, and A. Pascual-Leone, “Self-recognition and the right prefrontal cortex,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol.4, Issue 9, pp. 338-344, 2000.

- [56] S. Shimada, Y. Qi, and K. Hiraki, “Detection of visual feedback delay in active and passive self-body movements,” Experimental Brain Research, Vol.201, pp. 359-364, 2010.

- [57] W. Wen, “Does delay in feedback diminish sense of agency? A review,” Consciousness and Cognition, Vol.73, 102759, 2019.

- [58] M. Botvinick and J. Cohen, “Rubber hands ‘feel’ touch that eyes see,” Nature, Vol.391, 756, 1998.

- [59] P. M. Jenkinson and C. Preston, “New reflections on agency and body ownership: The moving rubber hand illusion in the mirror,” Consciousness and Cognition, Vol.33, pp. 432-442, 2015.

- [60] A. E. N. Hoover and L. R. Harris, “The role of the viewpoint on body ownership,” Experimental Brain Research, Vol.233, pp. 1053-1060, 2015.

- [61] E. L. Altschuler and V. S. Ramachandran, “A Simple Method to Stand outside Oneself,” Perception, Vol.36, pp. 632-634, 2007.

- [62] H. Hasegawa, S. Okamoto, K. Itoh, M. Hara, N. Kanayama, and Y. Yamada, “Self-Body Recognition through a Mirror: Easing Spatial-Consistency Requirements for Rubber Hand Illusion,” Psych, Vol.2, Issue 2, pp. 114-127, 2020.

- [63] S. Keenaghan, L. Bowles, G. Crawfurd, S. Thurlbeck, R. W. Kentridge, and D. Cowie, “My body until proven otherwise: Exploring the time course of the full body illusion,” Consciousness and Cognition, Vol.78, 102882, doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2020.102882, 2020.

- [64] I. Bianchi and U. Savardi, “Grounding naïve physics and optics in perception,” The Baltic Int. Yearbook for Cognition Logic and Communication, Perception and Concepts, Vol.9, pp. 1-15, 2014.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 Internationa License.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 Internationa License.