Abstract

Engaging consumers through social media is a successful way for firms to get users attention and allow them to participate in content creation by two-way communication. However, social network sites (SNS) also challenges brands as users have the ability to change the narrative expressed by a firm with non-favorable content. This paper presents a process-oriented model to study one of the most frequent types of negative word of mouth: complaint behaviors. Given the collaborative and social characteristics of SNS, and drawing on literature in social psychology and consumer behavior, we theorize that cognitive aspects (e.g. collective efficacy) largely mediate the effects of dispositional factors (perceived utility) on complaining. A survey to a nationally representative sample of online Chileans show that even after controlling for factors recognized by previous research able to influence negative word of mouth (e.g., trust in companies, altruism or exposition to complaints on SNS), the level of collective efficacy affects consumers’ willingness to complain in SNS and relate to others their experiences with brands, services or products.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

1.1 When Complaining Is the Advertising

Since 2009, social network sites (SNS) has become very popular, especially in countries such as US where more than 70% of the population are active users [1]. Not surprisingly, brands have also relied on SNS to engage with customers, as these communication channels present a cost effective medium that integrates communication and collaboration with users by co-creating content [2]. Further, SNS provides opportunities for content customization and delivers superior speed to the delivery of information communication and feedback [3]: social media can enhance a two-way communication between firms and customers, attaching customers more with the organisations’ brands [4]. Accordingly, research has considered social media as an effective mechanism that contributes to the firms’ marketing aims and strategy; especially in the aspects related to customers’ involvement, customer relationship management and communication [5, 6].

However, these opportunities have also developed challenges inherent to social media practices, as users can interact with brands through SNS during multiple stages of the consumption process including information search, decision-making and word of mouth. In fact, as SNS gives customers a convenient and direct line to engage openly with a brand, the balance of power with respect to both the control of a shared reality and the individual’s ability to express a brand narrative changed completely as customers can intervene [7]. Thus, similar to the transformation from advertising to integrated marketing communication, brands should also be aware of the possible moderations and consequences arising from participation through SNS [8].

Further, SNS have become one of the most popular options for dissatisfied customers to complain or voice their discontent [9], as SNS gives customers a convenient and direct line to the company, especially in times of crisis [10]. It also makes complaints visible to others through the user’s social network [11], significantly amplifying the range of influence compared to other channels [12]. This visibility may increase the sense of urgency for companies to respond quicker, because, both users and the company’s contacts are made aware of the problem. Given the relevance that SNS are acquiring as a channel for customer service [13, 14], it is important to understand how users perceive these social platforms for complaining and the impact it may have on branding.

Given the collaborative and social characteristics of SNS in facilitating mediated interactions among groups of individuals, we propose that SNS make users more cognizant of the problems experienced by other customers, enhancing their level of collective efficacy and augmenting their complaint behaviour. Accordingly, our interest in consumers’ collective efficacy emerges as a consequence of the capabilities for horizontal interpersonal communication highly embedded in these platforms, which facilitate customers’ ability to rebroadcast content (e.g., an answer from a company) adding personal commentaries, which in turn, enhance their capacity for discussion, engagement, and promotion of this information collectively.

We test the hypotheses related to consumers’ collective efficacy through a nationally-representative survey of Chilean internet users. In this way, we complement previous research [9, 13, 15] that has studied consumer behavior in SNS by applying the Bandura’s construct of collective self-efficacy to complaining. The approach is rooted in the idea that collective efficacy largely mediates the effects of dispositional factors on participatory outcomes (e.g. complaining in SNS). This mediation model moves beyond the simple stimulus–response perspectives of direct effects to a more process-oriented one. The model analyzes potentials antecedents that explain why users decide to socially complain through SNS, and then, controlling by those aspects, it draws attention to the ways in which users’ collective beliefs mediate the effects of the perceived utility of this medium on complaining. Consistent with this framework, our results show that even after controlling for factors recognized by previous research able to influence complaining (e.g., trust in companies, online privacy concern or exposition to others’ comments), the level of collective efficacy affects consumers’ willingness to complain in SNS.

1.2 Perceived Utility of Complaining

While existent research in consumer behavior indicates that individuals complain over products or services when they are dissatisfied [16], the same literature shows that dissatisfied consumers do not always express this unfavorable attitude to others [17]. To explain the likelihood of complaining, research has focused on the consumers’ perceived loss produced by the deficiency of the product or service [18]. However, the problem with this approach is that the feeling of dissatisfaction is a mental reaction to a perceived negative gap between what a person expects and what he or she gets. Since this perception is subjective and varies from person to person, individuals differ in their propensity to complain in similar situations [19]. To reduce this uncertainty, Kowalski [20] developed a theory of complaining that distinguishes between the two aspects that affect this behavior: people’s thresholds for experiencing dissatisfaction (dissatisfaction threshold) and the expressing dissatisfaction (complaining threshold).

Kowalski [20] explains that underlying both of these processes is a state of self-focused attention. This is an evaluative process where the individual compares the current events with his/her standards for those events. When the actual state of events falls below the individuals’ standards, the person experiences a discrepancy that leads him/her to feel dissatisfied. This feeling of dissatisfaction is what increases their motivation to reduce the discrepancy [21]. Before individuals decide to complain, however, they have to believe that complaining will actually serve to reduce the discrepancy and not incur additional undesired outcomes.

Kowalski [20] names this tradeoff as the perceived utility of complaining - the degree to which a person perceives that a complaint will be instrumental in promoting the achievement of a desired goal-, without affecting negatively other aspects, such as his/her image in the front of others (e.g. nobody likes to be stereotyped as a complainer). If a person, for instance, is dissatisfied with a perceived inequity in an ordered product (the dissatisfaction threshold is low), the individual is unlikely to complain unless he or she perceives that the expression of dissatisfaction will actually lead to accomplish a goal. The goal may be related to the product itself (i.e., materialist end) or to let other people know about it (i.e., altruistic or vengeance end). According to the perceived utility of complaining, individuals try to maximize the rewards to be gained by complaining and minimize the costs associated with it, regardless the consumers’ goals. “Such a cost-benefit analysis suggests that the utility of complaining is high when the rewards to be gained outweigh the costs of complaining.” [20, p. 181].

By applying this logic to complaining in SNS, it is possible to argue that individuals will not complain in SNS unless they perceive a high utility for complaining on this platform, such as receiving a satisfactory answer from the company or a valuable interaction with other users. Similarly, it is expected that positive experiences complaining in SNS will increase the perceived utility of this medium, specifically for egocentric and altruistic motivations, which according to the literature are the main drivers behind electronic word of mouth [9, 15]. That is, it is expected that users will feel satisfied complaining in SNS if they receive effective answers from the company or feedback from their contacts. Consequently, for those users who have experienced effective answers from companies and messages from contacts when they complain, it is expected that this perceived utility also lead them to complain more. Thus, it is possible to predict:

H1: Perceived utility will be positively related to frequency of complaining in SNS.

1.3 Social Learning as a Moderator for Complaining in SNS

Social learning theory offers a framework to explain why users who are exposed to others’ complaints in SNS may also be more prone to complain. Bandura [22] theorizes that most of the behavioral, cognitive, and affective learning acquired by individuals can be explained by social observations. Social learning theory suggests that humans have an advanced capacity for observational learning that enables them to rapidly expand their knowledge and skills through information conveyed by models in their immediate environments. According to this logic, individuals’ conceptions of social reality are greatly influenced by what they see, hear, and read. To a large extent, people act based on their images of reality. Therefore, these role models observed in their immediate environment have the potential to transmit new ways of thinking and behaving, which influences individuals to begin acting like them even without external incentives. Bandura [22] argues that the learning process involves four mains steps: (a) Attention: individuals must pay attention to the modeled behavior to learn; (b) Retention: it is necessary to remember the behavior in order to learn and reproduce the behavior; (c) Reproduction: individuals should have the ability to organize their responses and act according to the model behavior; and (d) Motivation: if new “learners” are not motivated to reproduce what they saw, they will not change their behavior.

Relevant to this research is the fact that SNS provide all these steps for social learning to occur, particularly when friends’ actions are aggregated in a content feed (Burke, Marlow and Lento [13]). The News Feed feature in Facebook or Twitter for example, allows newcomers to view friends’ or followed’ actions and recall them later. Users can also link or tag content, which makes their contribution more salient; this may motivate users to participate in creating content. Indeed, Burke et al. [13] found that friends’ behavior during newcomers’ first two weeks is one of the most important predictors for newcomers’ activities. Therefore, based on the social learning theory, it is possible to explain the positive relationship between exposition to complaining and this behavior on SNS as a reinforcement effect. Since these platforms facilitate users to be more aware of others complaints and they learn from their friends’ activities, it is possible to argue that they could “replicate” their actions. Thus, it is therefore reasonable to expect that users who encounter more these reactions will complain more in SNS.

-

H2a: Exposition to others’ complaints will be positively related to complaining

-

H2b: Exposition to others’ complaints will moderate the relationship between perceived utility and complaining in SNS.

1.4 Social Network Complaints: Towards a Collective Efficacy Model

Perceived self-efficacy is the term used to represent an individual’s perceived ability to influence his/her environment [22]. This sense of capability of acting effectively has been extensively documented by previous research as one of the key psychological variables that is able to explain individuals’ accomplishments in several areas such as civic participation [24], academic performance [25] and knowledge sharing [26], to name only a few. Research in consumer behavior has also considered self-efficacy as an important primary measure for achievements [27]. The literature has traditionally recognized two dimensions: one internal, that represents the perceptions of an individual’s ability to attain desired results using his/her own capacities and resources, and one external, that refers to people’s beliefs about the system’s responsiveness to their concerns [28]. However, concerted actions may also depend on perceptions of the group’s efficacy [29]. In fact, collective efficacy has also been used as a basis of the efficacy construct [30].

From an “internal” perspective, the notion of group efficacy can be conceptualized as the judgments that members of a group have about their capabilities to engage in successful action [29]. This emphasis is based on Bandura’s definition, which conceptualizes collective efficacy as the group’s shared belief in its conjoined capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given levels of attainment [22]. On the other hand, collective efficacy can also be understood in terms of the perceived responsiveness to the collective action that emerges from organized groups [31]. This second perspective is also relevant because does not focus on the abilities of the group but on how the system responds to the actions that emerge from the collective action. This paper considers both perspectives by integrating the beliefs that individual actions have the potential to transform the destiny of their group but with the responsiveness of the system to the collective demands for change. Therefore, drawing from the internal and external dimensions of the construct, we conceptualize consumers’ collective efficacy as a “user’s belief in the public’s capabilities, as a collective actor, to organize and execute the courses of action required to achieve that companies and sellers respond to their demands for change”.

Collective efficacy can be expected to operate in relation to complaining at the group level in a manner similar to self-efficacy at the individual level, but extending the concept of individual causality to collective agency exercised through a shared sense of efficacy [32]. Given the collaborative and social characteristics of SNS, we believe that these platforms can enable a sense of collective efficacy that, ultimately, might contribute to augment complaint behaviors in users. Moreover, by relying on mass information sharing to simplify social interactions, in which comments generated by peers most of the times precedes the information broadcasted by companies, SNS facilitate an ideal setting to discuss their experiences collectively. Thus, it may be argued that the dynamic of these conversations will make users more cognizant of discussions when they post comments about brands, and force them to process the information socially. However, unlike virtual communities, in which individuals share information by posting questions, providing answers, and debating issues based on shared interests [33], there are three affordances in SNS in particular that may lead users to an increased level of collective efficacy.

First, in SNS users not only create content but they also categorize collectively the information, which gives users the capability to tag all types of data. By marking content with descriptive terms (also called tags), users facilitate organization entries and access of information for other users as well. However, unlike tagging in Flickr or de.licio.us for instance, where users employ descriptive terms like “disappointed” or “cheated” to share semantic annotations, tagging in Facebook is the linking of a face in a photo or a public status update with a registered user. Thus, for complaint purposes the singling-out feature afforded by Facebook is relevant because “tagging” others highlights particular actions, making them not only visible to the “tagged” users but also to their entire network. In this way, social-tagging systems would help users to retrieve information about similar situations that other people went through, but also to be more aware of other users in their networks with similar problems, which force users in communities or networks to process the information socially.

Second, users in SNS are constantly evaluating content. These platforms allow users to evaluate content in two different ways: actively, by making comments or ranking specific information (e.g. reviewing a product), and passively, by tracking how users interact with the content offered in the platform (Web-browsing patterns). In fact, auto-generated indicators of information such as users’ traffic (e.g. counters indicating the number of contacts in Facebook, viewers in YouTube or followers on Twitter), are seen as one of the most relevant indicators for users to make quality judgments about the underlying content (Sundar [34]). Thus, one of the consequences of these affordances is that when users see someone complaining in SNS and how others react to it (likes, comments, etc.), these interactions would create aggregated data that allow users to process the information socially and respond collectively to it as well.

Third, users also have the ability through these new applications to form social networks by creating a profile within a bounded system: they designate other users as contacts, followers, fans, viewers, or friends. One of the main differences with virtual communities is that in SNS users have their own network of contacts (in addition to groups), and most of the activities are notified to all the users’ network, which can initiate social conversations between groups of users [11]. Our expectation is that these affordances will impact user’s belief in the public’s capabilities as a collective actor, to organize courses of action to achieve that companies and sellers respond to their demands for change. This, instead, will influence their tendencies toward complaining behaviors in SNS, such as their willingness to persist complaining given the support (e.g. likes or comments) that they may receive from their contacts. Thus, we expect that measurements of collective efficacy would help us to understand the impacts of SNS on this specific consumer behavior, by predicting:

-

H3a: Consumers’ collective efficacy will be positively related to complaining.

-

H3b: Consumers’ collective efficacy will mediate the relationship between perceived utility and complaining in SNS.

2 Methods

2.1 Sample and Procedure

This survey used an online panel provided by TrenDigital, a think tank based at the Catholic University of Chile. To overcome some of the limitations of using online surveys and assure a more accurate representation of the online national population, TrenDigital based the sample on the National Socioeconomic Characterization Survey (CASEN), a governmental survey ran every three years. Three variables were considered for this panel: gender (male: 48.7%; female 51.3%); age (18–34: 55%; 35–44: 20%; 45–64: 22%; 65+: 3%) and geography (Metropolitan Region: 47%, Fifth Region: 11%, Seventh Region: 10%, other regions south: 20%, other regions north: 12%). The selected panel members received the survey’s URL through an e-mail invitation. This invitation provided respondents information about a monetary incentive drawing for their participation. A first invitation was sent and then, to improve response rates, two reminders were sent during the next three weeks. 8,840 participants received the email and 1,070 responded the questionnaire, yielding a 12.1% response rate.

2.2 Dependent Variables

Complaining in SNS.

First respondents were asked whether they have complained in SNS against product or services offered by companies (36.1% answered yes). Then, for those who answered positively, respondents registered in a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always) how frequently they have complained against a product or service offered by a company: (1) on the company’s social media (e.g. it’s Facebook), (2) on a conversation with a friend via SNS, (3) on their own Facebook’s wall, (4) on their Twitter. An index was created with these 4 items (M = 2.48, SD = .94, α = .78). The questions to create the complaining scale in SNS were selected for two main reasons. First, Facebook (91%) and Twitter (44%) were the social media platforms with the higher penetration rates. And second, research has shown that users talk about their experiences not only with the companies’ accounts, but also in conversations with friends and in their own accounts, so we included these aspects as well.

2.3 Independent Variables

Perceived Utility of SNS for Complaining.

Based on egocentric and altruistic motivations, which according to the literature are two of the main drivers behind eWOM [9, 15], an averaged index that represents these motivations was created, with the questions: “thinking in your last complaints in SNS, were you satisfied with: (1) the answer given by the company, (2) the feedback gave by other users (interterm r = .19, M = 2.64, SD = .9).

Consumers’ Collective Efficacy.

Respondents registered their frequency of occurrence with a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Four questions from previous research [30] on an 5-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree (M = 3.9, SD = .9, Cronbach’s α = .86) were averaged to calculate the shared belief held by individuals about the consumer’s capabilities to perform a collective action (e.g. “If consumers organize they could influence the decisions made by the companies”), and the perceived responsiveness of the environment to the action (e.g. “Companies would respond to the needs of consumers if they organize and demand changes”).

Exposition to Others’ Complaint.

Using the same 5-point scale, we asked participants how frequently they see users complaining on SNS about products or services offered by companies in 9 areas, such as retailers (M 3.07; SD .71; cronbach .84).

2.4 Control Variables

We controlled for factors underlined as capable of affecting complaint behavior on SNS.

Trust in Companies.

It influences the perception about products and services offered by companies, diminishing negative aspects such as lower anxiety and vulnerability, which instead affects the willingness of consumers to talk about them (Matos and Rossi 2008). Using a 5-point scale ranging from “nothing” to “very confident”, respondents were asked how mucho do they trust in national, transnational and public companies (M = 3.04, SD = .7, Cronbach’s α = .68).

Online Privacy Concern.

Research has shown a negative relationship between privacy concern and different types of online behavior and attitudes toward online firms, such as purchase, trust in companies and word of mouth [35, 36]. It was measured using nine of the items from Buchanan et al.’s [37] Online Privacy Concern Scale (M = 3.72, SD = .81, Cronbach’s α = .89). An example items is “Are you concerned about people online not being who they say they are?” respondents answered on a 5 point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

Number of Brands Users Follow/Like in SNS.

Research [38] has shown that familiarity with brands affect how users process the information related to it: when brands are unfamiliar, negative information elicited more supporting arguments. Thus, we asked participants how many brands they follow/like/view in SNS in a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (No, I do not) to 7 (more than 30), with intervals of 5 brands per point (M = 3.54, SD = 1.8).

Frequency of SNS Use.

We used a 7-point scale ranging from never to almost all the time (M = 4.7, SD = 1.5).

Frequency of Online Purchasing.

Users who buy more frequently online may also have more exposed to complaints. We used a 5-point scale to measure how frequently users buy online ranging from never to almost all the time (M = 2.45, SD = 1.06). Participants were asked how much time they spent on four platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp) (range = 0 [do not use that social network] to 7 [use more than 6 h per day]; (Cronbach’s α = 0.62, M = 3.45, SD = 1.25).

2.5 Demographics Variables

We controlled for three demographics variables: age, using the same ranges of the panel (18–34: 57%; 35–44: 25%; 45–64: 15%; 65+: 3%), gender (58% females) and monthly income (less than 800 USD: 16.8%; 800–1,600 USD: 25.1%; 1,600–3,000 USD: 24.9%; 3,000–5,000 USD: 14.2%; 5,000–7,000 USD: 9.6%; more than 7,000 USD: 9.4%).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive Analysis

Before proceeding to the formal tests of the hypotheses, we wanted to understand the differences between those who have complained (n = 387 or 36.1%) and who have not complained (n = 683, or 63.9%) through SNS. Table 1 presents t-tests and chi-square tests between individuals who have and who have not complained on demographics and our interest and control variables.

Although female are more likely to complain via SNS than male users, this difference is only marginal. Regarding our control variables, complainers are heavier SNS users than non-complainers, they follow/like more companies in these platforms, but they have purchased fewer products online, which may be related to the idea that they are younger users so they still have a lower salary, as Table 1 shows. Interestingly, we did not find differences in the levels of privacy concern and trust in companies.

Concerning our interest variables, those who have complained have also been exposed to more complaints in SNS and they also perceive a higher utility for complaining in these platforms, however their consumers’ collective efficacy does not differ. The lack of difference in this last variable, however, may increase our confidence in the potential cause-effect relationship only among those users who interact more frequently with other users about problems with brands and have experienced collectively these aspects through SNS (Table 2).

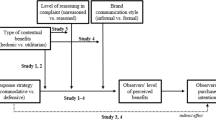

3.2 Multivariate Analysis

To test our hypotheses, a mediation regression analysis using a bootstrapping resampling method was conducted according to the specifications set out by Andrew Hayes’s PROCESS for SPSS using model five with one mediator and one moderator. As the Fig. 1 shows, perceived utility of complaining was entered as the independent variable (X), consumers’ collective efficacy as the mediator variable (M), exposition to others’ complaint as the moderator variable (W) and frequency of complaining was entered as the criterion variable (Y) in the model. Data analysis using 1,000 bootstrap simulations revealed that perceived utility of complaining in SNS was positively associated with frequency of complaining, with a significant total effect (b = .25, t (387) = 5.3, p < .001), corroborating H1. Interestingly, the direct effect of perceived utility was also statistically significant (effect = .3, SE = 0.11, p = < .001 [95% CI .007, .06]), suggesting that the mediation, in case of exists, it would be only partial.

Path model for the mediation analysis showing unstandardized path coefficients. Note. b = unstandardized regression coefficients with standard error are presented. All the control variables were entered in the model as covariates. Dotted line denotes the total effect of perceived utility on frequency of complaining on SNS. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Regarding the role of exposition to others’ complaints to complaining on SNS, the analysis showed a positive relationship between these two variables (b = .14, t (387) = 3.53, p < .001), confirming H2a. However, when it was tested as moderator, the variable was not significant. This means that the indirect effect of perceived utility on complaining through consumers’ collective efficacy does not increase linearly as users get exposed to others’ complaint, so it should be treated as one independent variable instead of a moderator one. Consequently we could not corroborate H2b. Concerning the influence of the other variables inserted in the model, neither the relationship between trust in companies and complaining in SNS was statistically significant, nor the relationship between online privacy concern and complaining in SNS. Interestingly, control variable such as frequency of SNS use, online purchasing and number of brands that consumers follow or like, are positively related to complaining in SNS. This means that users who spent more time in SNS, buy more online and follow more companies in SNS, they also complain more in these platforms.

Concerning the relationship between consumers’ collective efficacy and frequency of complaining, as H3a predicts, results show a positive effect (b = .17, p < .01). A similar relationship was found between perceived utility and consumers’ collective efficacy (b = .14, p < .001). Because both paths were significant, mediation analyses were tested using the bootstrapping method with bias-corrected confidence estimates. The 95% confidence interval of the indirect effects was obtained with 1,000 bootstrap resamples. Results of the mediation analysis confirmed the role of consumers’ collective efficacy in mediating between perceived utility of complaining and frequency of complaining in SNS (effect = .03, SE = .01, p < 0.01[95% bias-corrected bootstrap CI .01, .06]). Since the interval does not include zero, it is safe to conclude that the indirect effect was significantly different from zero, confirming the partial mediation of collective efficacy and our hypothesis H3b as well. The indirect effect was also statistically significant using the Sobel test, z = 2.1, p = .03 (Table 3).

4 Discussion

This paper presents a process-oriented model to study complaint behaviors on SNS. Overall it yields four main findings. First, it was found that higher perceived utility of SNS lead users to complain more on these platforms: users who perceive that companies respond satisfactorily to their demands on SNS and, receive feedback from other users about their experiences, show a higher disposition to complain in SNS. Second, by adding consumers’ collective efficacy as an intermediary process between the perceived utility and subsequent complaints, the results obtained extend current theoretical models that consider the perception that users have about a medium able to trigger a series of cognitive and expressive processes (e.g. consumers’ collective efficacy), which instead activates behavioral outcomes (e.g. complaining). Third, it was found that structural features of SNS through which consumers occurs (such as exposition to others’ complaints) positively affect complaining behavior. Fourth, results show that other aspects in the relationship between consumers and companies, such as the trust that consumer have on them, did not impact complaining behavior.

4.1 Theoretical Implications

This paper corroborates the idea that as communication technologies become more participatory, consumers are gaining greater access to information as well, which gives them more opportunities to engage with others in this networked realm and get a stronger ability to undertake online actions, such as complaining. Consistent with previous research that shows how the Internet satisfy the need for information in pre purchasing processes [35], we analysed some of the affordances in SNS that facilitate users to be socially informed and enhance discussion among them about the presented information. Based on the theory of perceived utility [20], the results show that individuals complain more in SNS when they perceive higher utilities in this platform, specifically when they satisfy egocentric and altruistic motivations through their complaints, two of the main drivers behind eWOM.

Regarding the indirect effect of perceived utility on complaining in SNS through consumers’ collective efficacy, two considerations are important. First, from a theoretical perspective, it was demonstrated that the framework is appropriated for understanding how SNS can facilitate and reflect community cohesion and enable a sense of consumers’ collective efficacy, that ultimately contribute to complaining behavior through this communication technology. By studying SNS as a structure that facilitates access to consumer information and promotes interactions through the integration of peer-generated and organizational content, we should conceptualize SNS as a source that it is constantly disseminating potential stories about experiences with products or services among contacts. This conceptualization is relevant since results show that the exposition to other consumers’ experiences dealing with companies, and the perceived utility of the channel to respond to dissatisfactions, lead users to believe that it is easier to mobilize collective efforts for solving the consumer problems. It activates their sense of agency and augments the likelihood of complaining.

One plausible explanation may be related to the higher opportunities for exposure to “social information” presented in SNS: social media promotes a participatory dynamic in which discussants can see what their contacts collectively think about others’ experiences. They can even get collective answers from their networks to personal inquiries. By allowing mass information-sharing mechanisms, users of these social platforms can simultaneously communicate with all their contacts and networks while responding to information or comments posted by users. Therefore, it is likely that SNS users will find resources in their networks when they want to clarify a situation that they go through a company. We believe that this exposition augments consumers’ exposition to spheres in which reflective storytellers operate and take collective actions to solve problems.

The second consideration that results from this study suggests that social feedback exerted by users in forms of dialogues may impact this form of psychological empowerment, especially when others indicate how you should complain or respond to a company or service. As explained above, the capabilities for interpersonal and mass communication highly embedded in these social media platforms enable users to inform their contacts and receive “collective” feedback from them as well. This may increase opportunities for consumers to see how groups of people respond to individual complaints. As our study showed, consumers also learn and replicate what they see online. This finding is relevant because SNS allow consumers to share their thoughts with their entire network and learn what their network is thinking or what they commented just by logging onto their own accounts. This non-invasive form of communication may augment exposition to complaining behavior and affect users’ actions as well.

4.2 Practical Implications

When costumers complain publicly through a company’s social media accounts, not only the seller becomes aware of the problem, but also its followers, likers, and viewers. Even more, the complainers’ contacts could also learn about the problem, and each time that one of them interact with the complaint posted, new “networks” could potentially learn about the situation. This higher visibility, compared to more traditional channels such as regular phone calls, may force the seller or service behind the complaint to act in order to solve the problem and reduce the visibility attained by it. Thus, community managers should be trained to recognize the source behind the problems in order to be able to answer as soon as they can.

Interestingly, however, the results of our study show that in this regard, the perceived utility of SNS leads users to complain more on these platforms. This basically means that customers who perceive that companies respond satisfactorily their demands on SNS, would motivate them to complain even more through that channel. Thus, based on the results it is possible to conclude that “good” and “fast” answers are going to attract more complainers. In other words, as companies try to respond as soon as possible to costumers, they are also motivating them to complain more through SNS, and since users also “replicate” the behaviors that they observe online, it may increase even more the likelihood of complaining.

Furthermore, these waves of complaining may also affect negatively the brand’s reputation. If consumers see constantly how other users complain against brands in their social media accounts, it is likely that the company’s image will be affected. On the other hand, if companies do not respond to users’ accusations, it may be affected even more for the situation. The result presents companies with a paradox. How should companies respond? Based on our results, we suggest that companies should look for a balance, where even though they should try to respond as much as they can, they also should know that these compromises might motivate users to complain even more. In these particular cases, sometimes “less” would be “more.”

4.3 Limitations

However, the study has several limitations that deserve mention. First, the analyses are based on cross-sectional data. Although we based our causality approach in pivotal research, the study could not be fully confident in causal relationships among variables, and the question of causal direction needs verification through longitudinal and/or experimental approaches. Second, even though our model took several variables into account (i.e., demographics, SNS use, privacy concern), future studies should explore whether other variables related to individuals’ activities on SNS could impact complaint behavior. And third, we used self-reported data and not actual observations of how users complain on SNS, and the limitations of this approach are painfully well-known.

Despite these limitations, this paper still makes a contribution to theory and practice. The interest in how users today are interacting with companies and services through SNS have gained a lot of attention from scholars in the last couple of years. This paper presents a process-oriented model to explain how cognitive aspects (e.g. consumers’ collective efficacy) mediate the effects of dispositional factors (perceived utility) on complaining. We believe that our findings are valuable for both scholars and practitioners. One the one hand, we could integrate theoretical insights from different areas in a model able to explain complaining on SNS, but on the other hand our results are also interesting for marketers and corporate communicators, as the analyses showed that complaints in SNS not necessarily need to responded massively and in a short period of time.

References

Smith, A., Anderson, M.: Social media use in 2018. Pew Internet & American Life Project, Washington, DC (2018)

Jung, A.R.: The influence of perceived ad relevance on social media advertising: an empirical examination of a mediating role of privacy concern. Comput. Hum. Behav. 70, 303–309 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.008

Shilbury, D., Westerbeek, H., Quick, S., Funk, D., Karg, A.: Strategic Sport Marketing, 4th edn. Allen & Unwin, Sydney (2014)

Alalwan, A.A., Rana, N.P., Dwivedi, Y.K., Algharabat, R.: Social media in marketing: a review and analysis of the existing literature. Telemat. Inform. 34(7), 1177–1190 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.05.008

Filo, K., Lock, D., Karg, A.: Sport and social media research: a review. Sport. Manag. Rev. 18(2), 166–181 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2014.11.001

Knoll, J.: Advertising in social media: a review of empirical evidence. Int. J. Advert. 35, 266–300 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1021898

Quinton, S.: The community brand paradigm: a response to brand management’s dilemma in the digital era. J. Mark. Manag. 29(7), 912–932 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2012.729072

Felix, R., Rauschnabel, P.A., Hinsch, C.: Elements of strategic social media marketing: a holistic framework. J. Bus. Res. 70, 118–126 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.05.001

King, R.A., Racherla, P., Bush, V.D.: What we know and don’t know about online word-of-mouth: a review and synthesis of the literature. J. Interact. Mark. 28(3), 167–183 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2014.02.001

Oh, O., Agrawal, M., Rao, H.R.: Community intelligence and social media services: a rumor theoretic analysis of tweets during social crises. MIS Q. 37(2), 407–426 (2013). https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.2.05

Kane, G.C., Alavi, M., Labianca, G.J., Borgatti, S.: What’s different about social media networks? A framework and research agenda. MIS Q. 38(1), 274–304 (2014). https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2014/38.1.13

Dewan, S., Ramaprasad, J.: Social media, traditional media, and music sales. MIS Q. 38(1), 101–121 (2014). https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2014/38.1.05

Jansen, B.J., Zhang, M., Sobel, K., Chowdury, A.: Twitter power: tweets as electronic word of mouth. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 60(11), 2169–2188 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21149

Gallaugher, J., Ransbotham, S.: Social media and customer dialog management at Starbucks. MIS Q. Exec. 9(4), 197–212 (2010)

Cheung, C.M., Lee, M.K.: What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online consumer-opinion platforms. Decis. Support Syst. 53(1), 218–225 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.01.015

Hunt, H.K.: Consumer satisfaction, dissatisfaction, and complaining behavior. J. Soc. Issues 47(1), 107–117 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1991.tb01814.x

Morel, K.P., Poiesz, T.B., Wilke, H.A.: Motivation, capacity and opportunity to complain: towards a comprehensive model of consumer complaint behavior. ACR North Am. Adv. 24(1), 464–469 (1997)

Andreasen, A.R., Manning, J.: The dissatisfaction and complaining behavior of vulnerable consumers. J. Consum. Satisf. Dissatisf. Complain. Behav. 3, 12–20 (1990)

Thøgersen, J., Juhl, H.J., Poulsen, C.S.: Complaining: a function of attitude, personality, and situation. Psychol. Mark. 26(8), 760–777 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20298

Kowalski, R.M.: Complaints and complaining: functions, antecedents, and consequences. Psychol. Bull. 119, 179–196 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.179

Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., Hamilton, J., Nix, G.: On the relationship between self-focused attention and psychological disorder: a critical reappraisal. Psychol. Bull. 110, 538–543 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.110.3.538

Bandura, A.: Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 52(1), 1–26 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-839X.00024

Burke, M., Marlow, C., Lento, T.: Feed me: motivating newcomer contribution in social network sites. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 945–954 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1145/1518701.1518847

McPherson, J.M., Welch, S., Clark, C.: The stability and reliability of political efficacy: using path analysis to test alternative models. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 71(2), 509–521 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055400267427

Niemi, R.G., Craig, S.C., Mattei, F.: Measuring internal political efficacy in the 1988 National Election Study. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 85, 1407–1413 (1991). https://doi.org/10.2307/1963953

Zimmerman, B.J., Bandura, A., Martinez-Pons, M.: Self-motivation for academic attainment: the role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. Am. Educ. Res. J. 29(3), 663–676 (1992). https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312029003663

Hsu, M.H., Ju, T.L., Yen, C.H., Chang, C.M.: Knowledge sharing behavior in virtual communities: the relationship between trust, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 65(2), 153–169 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2006.09.003

Bearden, W.O., Hardesty, D.M., Rose, R.L.: Consumer self-confidence: refinements in conceptualization and measurement. J. Consum. Res. 28(1), 121–134 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1086/321951

Gecas, V.: The social psychology of self-efficacy. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 291–316 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.15.080189.001451

Van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., Spears, R.: Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: a quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychol. Bull. 134(4), 504–535 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504

Yeich, S., Levine, R.: Political efficacy: enhancing the construct and its relationship to mobilization of people. J. Community Psychol. 22, 259–271 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(199407)22:3<259::AID-JCOP2290220306>3.0.CO;2-H

Caprara, G.V., Vecchione, M., Capanna, C., Mebane, M.: Perceived political self-efficacy: theory, assessment, and applications. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 39, 1002–1020 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.604

Yates, D., Wagner, C., Majchrzak, A.: Factors affecting shapers of organizational wikis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 61(3), 543–554 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21266

Sundar, S.S.: The MAIN model: a heuristic approach to understanding technology effects on credibility. In: Metzger, M.J., Flanagin, A.J. (eds.) Digital Media, Youth, and Credibility, pp. 72–100. The MIT Press, Cambridge (2008)

Eastlick, M.A., Lotz, S.L., Warrington, P.: Understanding online B-to-C relationships: an integrated model of privacy concerns, trust, and commitment. J. Bus. Res. 59(8), 877–886 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.02.006

Wirtz, J., Lwin, M.O., Williams, J.D.: Causes and consequences of consumer online privacy concern. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 18(4), 326–348 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1108/09564230710778128

Buchanan, T., Paine, C., Joinson, A., Reips, U.: Development of measures of online privacy concern and protection for use on the internet. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 58(2), 157–165 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20459

Ahluwalia, R.: How prevalent is the negativity effect in consumer environments? J. Consum. Res. 29(2), 270–279 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1086/341576

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Halpern, D., Kane, G.C., Montero, C. (2019). When Complaining Is the Advertising: Towards a Collective Efficacy Model to Understand Social Network Complaints. In: Meiselwitz, G. (eds) Social Computing and Social Media. Communication and Social Communities. HCII 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 11579. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21905-5_26

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21905-5_26

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-21904-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-21905-5

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)