Abstract

The goal of this research is to discuss and develop a chatbot, named Edgard, in the fields of electronic literature, interaction design and Artificial Intelligence (AI). It will address technologies and its contradictions, pointing out its significant role as a platform for creativity, innovation and knowledge production, as well as the importance of critical thinking in the ethical application of these technologies, whose emergence reveals a new industrial revolution.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies represent progress as significant as those that in previous centuries provoked profound social, political and environmental impacts. The so-called industrial revolutions signal an accelerated progression whose aspects, when analyzed, are contradictory. If, on the one hand, humanity benefited from the scientific advances made available through the use of technological products, such as improving their life expectancy and quality and giving access to diversified cultural manifestations, on the other, is at the core of the environment’s degradation, exacerbated wealth concentration by an elitist minority and the polarization of opinions capable of producing social tensions amid the circulation of false information, showing itself capable of interfering in democratic processes around the world.

The emergence of AI reminds us of analogous situations already experienced, such as the emergence of the first steam engines in the eighteenth century. It is, therefore, necessary to consider its use from a historical perspective and its inherent contradictions. We sought to analyze the use of AI technologies by designing a chatbot, Edgard, conceived by the intersection between art, science, and technology. This paper presents discussions held in 2018 by a research group on Interactive Environments composed of professors and students from Senac’s University Center Bachelor’s Degree in Digital Design. This project aims to discuss the understanding of technologies’ roles as the primary platform for innovative thinking. Following this point of view, by supporting creative processes, AI technologies unbalance the pros and cons in favor of the former. However, this will only be possible if the use of these technologies occurs in critical circumstances based on experience given by previous industrial revolutions. We are now aware of being on the threshold of a new evolutionary cycle which, as in previous ones, has in its core contradictions and reasons for both excitement and concern. It is true that the choice to use AI technologies in society has diffuse origins, and its usage will cause a significant impact very soon. However, it is also true that, despite the various goals, ethical issues lie at the heart of this development.

2 Technology and Modernity

Technology is the knowledge field that allows us to apply know-how, the appropriation of artifacts or tools to build other artifacts or tools. This appropriation can be either merely technical when the individual explores technological resources without worrying about its origins or improvement, or technological when the activity leads to creative processes that are capable of allowing new developments. Altogether, technology shares many of its knowledge with science. In many times it is possible to perceive a synergistic action between the knowledge fields in which new technologies leverage new scientific expertise, or when scientific discoveries allow the emergence of new technologies.

Technologies characterize the modern period. Cupani [1] brings the concept of a device recognizing that, in addition to the social, political and economic aspects, technological artifacts must have its pragmatic character identified. Devices, such as commodities, provide services:

“One must recognize in technology a primary phenomenon, which has its key in the existence of the devices that provide us with products (commodities), that is, goods and services, whether it is the electric heater, which gives us heat, of the vehicles, which allows us to move quickly and relatively freely, or the television set, which gives us information and entertainment” [1].

As consumer goods, technological artifacts are the subject of marketing interest. Taken from the Enlightenment perspective, the consumption of these devices would meet the aspiration to liberate humanity from hunger, pain, and labor. Besides, technology can be attributed to the potential for raising cultural standards and life. However, as pointed Cupani [1], technology and science alone cannot be attributed to socio-cultural changes experienced in industrially developed countries.

“It is not enough, therefore, to understand technology by paying attention to its dominated nature, or its association with science. Scientific progress and its application to practical purposes are imperative to the existence of most technological inventions, but science, by itself, cannot provide a direction or explain why technology has become a lifestyle” [1].

Cupani [1] points out that, in order to better understand the technical device and the consequences of its use, one must distinguish between traditional technology and modern technology. The former maintained close social, cultural and ecological relations with its place of origin, while technologies, uncoupled from their environment, merely connect means and ends. In this sense, devices can be used independently of its context and freely combined. Devices become conceptually ambiguous. This scenario can give us an understanding of how much the technology consumption feeds a dream of a better, safer and more valuable life, at the same time that culture becomes the space for the exercise of addiction, pleasure, and security, making the paradigm of technology, not an option, but an imposition. The efficiency of technical devices floods the brain of dopamine [2] as an emotional consequence of the efficiency of the immediate response and the sense of security that interactive technologies provide. The question of efficiency is an aspect that comes when the theme is technology, and that it is of our interest because it is in this aspect that most significant consequences of the use of contemporary digital technologies, among them AI reside.

2.1 Technology and Society in Economics, Art and Design

In the context of capitalism, the best measure of efficiency is profit. In this sense, technologies can be used at both ends of the market, in the consumption of commodities and its production as tools of goods and services. Cupani [1] brings to his arguments the thoughts of Andrew Feenberg to build the connections between technology, capitalism, and efficiency.

“Capitalism (and bureaucratic socialism), sustains Feenberg, fosters technological achievements that reinforce hierarchical and centralized social structures and, in general, control “from above,” in all sectors of human life: work, education, medicine, law, sports, media, and many others. There is, in short, a “generalized technical mediation” at the service of privileged interests, which reduces human possibilities everywhere, in the name of efficiency, imposing everywhere, as visible measures, discipline, vigilance, standardization” [1].

Nonetheless, there is in this simplification process, and cultural impoverishment resulted from generalization that serves privileged interests by efficiently securing a profit, a breach for the rupture imposed by the “hegemony of the technical code.” Cupani [1] reminds us that society does not respond linearly to the stimuli to which it is exposed. There is a “room for maneuver” that subtracts from capitalism its absolute control. Alternatives for reinvention can appear in the game of technological usage. This aspect, which here recovers the subject of the technical device’s ambiguity, is also present in the Simondonean thought. The “margin of indetermination” [3] for Simondon implies the absolute perfection of the machines, contradicting the first impression that the technological advance is attributed to automatism. For the philosopher, who studied technology from a humanist perspective, the increase in the margin of indetermination allows a more complex dialogue between the technical beings (especially the machines) and the living beings. This dialogue allows innovation and diversification of possibilities and cultural experiences provided by technical objects [4]. It is no mere coincidence that contemporary art offers a space for reflection and practice where artists explore the Simondonean concepts of “margin of indetermination” and “superabundance” [5].

“As objects and natural resources are organized in a system, the potential brought by each of them in the dispersion state is updated in specific power lines. This should explain why systematic ordering does not produce results limited to the initial expectations of problem resolution. The update of each subset potential does not produce a simple sum because, in the systematic frame, there is a real amplification of the obtained effects’ potential. The conditions of the problem are overcome because the invention recreates new potentials, upgradable by new inventions, establishing new genetic cycles of images” [6].

The intersection of artistic and technological production fields is a space for reinventing the devices. Practices within the art universe develop new technical objects as a result of the re-signification of others, integrating them into new symbolic systems to produce non-linear results, different from the mere sum of its parts. Devices are reorganized poetically in the creation of narratives, having in mind the aesthetic experience. In this respect, such practices approximate Art and Technology of Conceptual Art.

Although this reinvention process produces impacts on culture, as did works as the “Fountain”, 1917, by Duchamp [7], or the “GFP Bunny: transgenic bunny”, 2000, by Kac [8], is the systematic use of technical devices that have attracted the attention of philosophers, historians and scholars of technology, especially when it comes to the use of AI. Harari [9], in a somber perspective of the future, considers the possibility of the decoupling between liberalism and capitalism. He criticizes the real motives of liberalism, which guarantees individual freedom to citizens in democratic societies in a game of economic and political interests.

“[…] giving people political rights is good because the soldiers and workers of democratic countries perform better than those of dictatorships. Allegedly, granting people political rights increases their motivation and their initiative, which is useful both on the battlefield and in the factory” [9].

2.2 AI and Its Impact on the Job Market

Recognizing in the humanist discourse of the liberal ideology a strategy to conceal his real interests, Harari [9], given the technological advances represented by the use of intelligent algorithms, foresees an even more disastrous situation for humanity. The use of these technologies will suppress men and women’s military and economic value [9]. The ability to “handle a hammer or push a button” loses its relevance to the machines’ efficiency. The reason for this lies in the fact that everything, as far as the breadth of computers and culture itself is concerned, advances quickly. Kurzweil [10] recalls Moore’s law when referring to the acceleration in the computing field, communication network and other parameters linked to that technological breadth. According to this law, the number of components integrated into the microprocessors grows exponentially over time. This increase results in assigning computers greater computing power. Human intelligence, extra somatized in machines, has made them more efficient than us in various tasks. The concept of Singularity, brought by Kurzweil [10], which seeks to understand intelligence and its relation to the human brain, allows the understanding of its mechanisms and the construction of machines as complex as the brain itself.

“The goal of the project is to understand precisely how the human brain works and then use these unveiled methods to better understand ourselves, fix the brain when necessary and - most pertinent to the point of this book - to create even smarter machines” [10].

If we consider the emergence of devices with embedded AI used in the industry, we will have the impression that the Singularity, as Kurzweil predicted, seems very close to happening. However, that may not be good news for humans. When it comes to considering social impacts on the use of AI technologies, Harari [9] presents pessimism about how “unimproved” humans will be completely useless and can be easily replaced by robots and 3D printers in manual labor. In fact, such substitution of humans by intelligent machines will occur in many areas of productive activity. From stockbrokers to lawyers, doctors and professors can be replaced by smart technologies that never tire or lose their patience, and they can devote 100% of their time in the execution of their tasks.

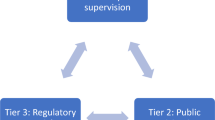

In the CIGI Papers publication of July 2018 by the International Center for Innovation and Governance, Twomey [11] presents a study on the progress in the adoption of AI and Big Data technologies, within the G20Footnote 1. In this study, the author presents a propositional scenario for the gradual adoption of these technologies in order to minimize their social impacts. The numbers presented in this document express the relevance and scale of the issue.

For example, KPMGFootnote 2 International [12] reports that “between now and 2025, up to two-thirds of the $9 trillion knowledge-market workers may be affected. The Bank of England estimates that robotic automation will eliminate 15 million jobs from the UK economy over the next 20 years. Digital technologies will conceivably shift the jobs of 130 million knowledge workers - or 47% of total US jobs - by 2025. Throughout the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, about 57% of jobs are threatened. In China, this number rises to 77%” [11].

In this scenario, governments should take precaution methods so that 375 million workers (3–14% of the total workforce) can adapt. Although it is a significant figure, it is a small contingent when compared to the total of affected workers. Low-income, indigenous, and other exclusion and vulnerability groups have to be considered. Eubanks [13] raises a red flag for the poverty problem in the context of the massive adoption of intelligent automation technologies:

“What I found was impressive. Across the country, poor and working-class people are targeted by new tools for managing digital poverty and, as a result, face life-threatening consequences. Automated eligibility systems discourage us from claiming the public resources needed to survive and thrive. Complexly integrated databases collect your most personal information, with little guarantee of privacy or data security, while offering almost nothing in return. Predictive models and algorithms identify them as risky investments in problematic countries. Vast networks of social service, law enforcement, and neighborhood surveillance make each movement visible and offer its behavior to the public, commercial, and governmental scrutiny” [13].

The author considers that, as in previous technologies of poverty management, the systems of monitoring and automatic decision-making disguise the poverty of the professional middle class. The poor who, according to the author, has been criminalized by their condition, may have their situation aggravated by the use of algorithms, databases and risk models capable of eclipsing their situation of vulnerability. As a result of this ethical divergence, the use of these technologies will allow one to decide “with comfort” who will have access to food or a roof to live under [13]. This concern is also present in Twomey’s [11] study of bias in encoding or the distorted selection of data input from intelligent systems, resulting in significantly misleading results under the glaze of independent automated decision-making.

2.3 Technology as a Platform for Creativity and Innovation

Faced with this worrying and dystopian scenario, where then will there be room for citizenship? The path towards this reflection entails the question of creativity. Harari [9] reminds us that art offers the “final and definitive sanctuary” for humanity. The creative process would act as an outlet where humans can exercise their creativity, an ability unique to them. However, it seems that the machines are executing algorithms so sophisticated that even in this regard doubts about human uniqueness in art are beginning to emerge.

“Why are we so sure computers will be unable to better us in the composition of music? According to the life sciences, art is not the product of some enchanted spirit or metaphysical soul, but rather of organic algorithms recognizing mathematical patterns. If so, there is no reason why nonorganic algorithms could not master it” [9].

It is not possible to reflect on creativity if we do not discuss consciousness. It is a complex concept on which there are different and conflicting understandings. Damásio [14] considers it one of the pillars for the evolution of the human species. For him, consciousness is at the core of creative, ethical, moral, and emotional processes.

“Without consciousness - that is, a mind endowed with subjectivity - you would not know how to exist, let alone know who you are and what you think. If subjectivity had not arisen, even modestly at first, in creatures far simpler than we, memory and reasoning would not have expanded in the prodigious way they did, and the evolutionary path to language and an elaborate version of consciousness would not have been paved. Creativity would not have blossomed. There would be no music, no paintings, no literature. Love would never have been love, just sex. Friendship would have been mere cooperative convenience. Pain would never have become suffering - not a bad thing in itself - but an equivocal advantage since pleasure would not have become happiness either. If subjectivity did not make its drastic appearance, there would be no knowledge and no one to take notice, and consequently, there would be no history of what creatures did through the ages, no culture would have been possible” [14].

If consciousness and creativity are related to cognitive abilities, then the question is whether intelligent machines can be conscious. It is, therefore, necessary to distinguish conceptually creative consciousness and intelligence. The latter could be understood in terms of information processing components underlying complex reasoning and the solution of problems and tasks such as analogies and syllogisms. Intelligence involves the processing of information, and mathematical modeling (algorithms) used to decompose cognitive tasks into their elementary components and strategies [15].

The question of consciousness implies that cognitive processes are objects of self-awareness, a cognitive ability that allows the intelligent agent to witness his or her actions to be endowed with subjectivity [14]. Kak [16], when considering humans and machines, recalls that although machines can quickly realize cognitive processes, they are not able to construct a subjective perception and assign meanings to what they do. The author recalls that Alan Turing in 1936 proved that there is no general algorithm to solve the Halting Problem, which states that in the presence of a given input, the program should terminate its activity or continue to execute it forever. However, a conscious mind can discern between stopping or continuing. In other words, “consciousness is not computable.”

“To our intuition, consciousness is a category that is dual to physical reality. We grasp reality in our mind and not in terms of space, time, and matter. This experience varies based on brain states, and it can be concluded that non-human experiences it differently from us. It is also notable that in our conscious experience we are always outside the physical world and witness ourselves as separate from our bodies. Even in scientific theory, such as in classical mechanics, the observer is far away from the system, even though there is no explanation of the observer within the theory” [16].

Damásio [14] considers consciousness as the cognitive mechanism underlying social processes, seeing in it the aspect that boosts creative processes present in the stories we tell. Narratives, as creative processes, are at the foundation of stories that give concreteness to societies, promoting the homeostasis of their institutions.

“Provided with conscious reflection, organisms whose evolutionary design was centered around the regulation of life and the tendency to homeostatic balance that invented ways to comfort for those who suffer, rewards for those who comfort them, injunctions for those who caused damages, norms of behavior aiming to prevent evil and promote good, and a mixture of punishments and preventions, penalties and approval. The problem of how to make all this wisdom understandable, transmissible, persuasive, workable - in a word, how to do it successfully - was faced, and a solution found. Storytelling was the solution - storytelling is something that brains do, naturally and implicitly. Implicit narratives have created our egos, and it should come as no surprise that it permeates the fabric of human societies and cultures” [14].

Following this logic, the process of narrative construction, which depends on consciousness, is also inherently creative. For this reason, creativity could only occur in conscious minds. However, this perspective does not have full support in the scientific community. Scholars who consider it valid meet around the Big-C Hypothesis, according to which consciousness is a separate category of physical reality [16]. On the other hand, there are those who, in contrast to that hypothesis, consider the mind from emergency phenomena. A conscious mind emerges as a result of the structural complexity of the brain. In this respect, which brings together those approaching the Little-c Hypothesis, a conscious mind, supported by digital circuits, could emerge from a complexity analogous to the human brain. Kurzweil, as we have seen above, presents his arguments on this theoretical side. It is a complex debate and far from being appeased by consensus. Aside from this, there is the fact that the available technologies have not yet allowed the development of technological devices comparable to brain complexity in order to support a conscious mind based on silicon transistors.

What we have at the moment in terms of digital technologies and the use of AI is a critical situation that points to many ethical, moral and political gaps in the application of technologies with disruptive potentials that will change the social prospect in less than a decade. If there is an important aspect to consider here is creativity. Moreover, this leads us to consider the perspective given by Simondon [5] when he brings the question of “margin of indetermination” and “overabundance”. We are referring to the potential of AI technologies in Art and the fields of creative activity such as Design. Dewey [17] corroborates this perspective when he considers that the function of art is to seek the expectation break, to unbalance belief systems, having in perspective the search for new points of balance in new thought configurations.

It is considered, therefore, following the arguments presented here, that the use of technologies can be considered a platform for creative activity, capable of supporting narratives whose experiences open new prospects to consciousness, expanding reality. Despite the scientific advance in the neurosciences, the consciousness constitutes a knowledge field still little explored. Also, worse than that, it is the fact that those who seek to study these limits of knowledge can be defamed and the results of their studies, labeled as charlatanism [9].

“In the future, however, powerful drugs, genetic engineering, electronic helmets and direct brain-computer interfaces may open passages to these places. Just as Columbus and Magellan sailed beyond the horizon to explore new islands and unknown continents, so we may one day set sail towards the antipodes of the mind” [9].

Regarding the antipodes of the mind, Harari refers us to the novelist and philosopher Aldous Huxley, who makes similar observations when describing his personal experience with psychoactive substances in two of his works: “The Doors of Perception” and “Heaven and Hell.” This discussion is also the subject of Shannon’s study [18], in the book “The Antipodes of the Mind.” Creative advances provided by the innovative processes of art and design can lead us to the expansion of consciousness in a proportion almost incommensurable, similar to that which constitutes the visible range of the visible electromagnetic spectrum, concerning that which is invisible. Harari [9] asks whether this proportion, about 10 trillion, would not be analogous to the spectrum of all mental states, of which we discover only a tiny fraction. The idea of using a conversational robot in the context of literature, which we describe below, is both an artistic experience and a study in the field of Interaction Design in an approach that integrates creative processes and cognitive sciences, taking into account aesthetics, transformative experiences capable of expanding consciousness, bringing to our perception the entirety in its complexity.

2.4 Dialogue-Based Narrative Systems

The development of conversation-based narrative systems can be considered a genre of electronic literature, a variant of Hypertextual Fiction or Interactive Fiction. Defined by hypertextual links, they can offer a new context for non-linearity in literature and the reader’s interaction with the text itself. The ability to choose between links in order to move from one informational node to another stimulates a new approach to reading and understanding literary pieces. Herewith, the author and reader now share the literary work’s creative process towards a personalized experience.

“Interactive narrative is a form of digital interactive experience in which users create or influence a dramatic storyline through their actions. The goal […] is to immerse users in a virtual world such that they believe that they are an integral part of an unfolding story and that their actions can significantly alter the direction or outcome of the story” [19].

Implementing chatbots in narrative contexts instigates primitive aspects of the homo sapiens, leading to powerful experiences. Dialogues now own a significant portion of our interpersonal interactions through social media and text messages. Our affinity with the medium derives from a very primitive aspect in our brains which is the need to continuously expand new social connections [20]. The union between the expansion of AI studies and the exploration of conversational media results in new expressive opportunities for conversations storytelling.

“Combining real-time learning with evolutionary algorithms which optimize chatbot ability to communicate based on each conversation held means that the potential for storytelling is now possible” [21].

Cavazza and Charles [22] consider dialogue an essential part of entertainment media, with “relations between narrative roles and their translation in terms of linguistic expression as part of intercharacter dialogue” carefully investigated in Bremond’s narrative theory [23].

“The interaction between characters constitutes most of the narrative action and as such should be not only meaningful but should be staged with the same aesthetic preoccupations which characterize the sequencing of narrative actions to constitute a story. This means that the dialogue itself should be staged through a choice of linguistic expressions which should display the properties of a real dramatic dialogue” [22].

The concern expressed by Cavazza and Charles [22] when it comes to how natural the dialogues sound relates to how Riedl and Bulitko approach interactive narratives, pointing out that natural interactions are an essential determinant for their success. The game “Oxenfree” [24], easily framed by the definition of interactive narratives, portrays dialogue as the primary skill of the character Alex and represents navigation links within the story. The naturalness of this process excludes any possibility of breaking the magic circleFootnote 3 and consequently makes the user believe that he is, indeed, an integral part of the unfolding story, resulting in a positive experience.

3 Edgard, a Literary Project for a Conversation Robot

Edgard, the chatbot, is the result of a study within the design field. Its development seeks to point out possibilities in Interaction Design intersecting with Art, in this particular case, Literature and Narrative Games. Many terms such as digital assistants, conversational agents, conversational interfaces, conversation robots, among others can refer to chatbots. In this work, we use the term chatbot from the definition of Dale [26] that defines it as any software application that involves dialogue with a human being through natural language.

The book “Mentiras de Artista” (Artist’s Lies) by Fábio [27] inspired the creation of Edgard. In his writing, he considers how the artist appropriates technology and re-contextualizes his production outside the craft realm, following the inverse path of conceptual art. The author then discusses the truth that lies in his process. Nunes describes his artistic experiences with AI and how he uses deceit as the raw material of his work to expose how the fake in social media shows truths (regularities) about us and the world we build every day (Fig. 1).

The method employed to discuss the fake issue in communication networks was the Eliza algorithm, created by Weizenbaum [28] in 1966. The robot was designed to mimic a psychoanalyst in consultation with his patient, instigating the subject to insert sentences into the system that would store the computer’s memory and use it in the creative development of a typical dialogue, such as occurs in a psychoanalysis session. Nunes installed a version of Eliza on a server to present it on Mimo Stein’s, a fictional character introduced as a young artist working with technology, website. As part of the imaginary construction of Mimo Stein, the professional chatted with the audience. Texts, written by Nunes [27], introduces the artist through the website without mentioning that it is a chatbot, building the narrative of Mimo Stein. Hence the artist’s lie who turns him into a “producer of events” [27]. By creating interactive narratives with its users, Nunes produces a context capable of integrating creations anchored in the circumstances provided by Mimo Stein.

“Art considered as contextual will gather all creations that anchor in the circumstances and show themselves desirous of “weaving with” the reality. A phenomenon that leads the artist to stop choosing classical forms of representation (painting, sculpture, drawing, or video when exposed conventionally) preferring the direct and intermediate relationship of the work with the ‘real’” [27].

Mimo Stein is a character that only exists on the Internet, but for those who interact with it, it is a real person, capable of concrete, objective, and therefore genuine attitudes. This is the Eliza Effect, an update on the Alan Turing Imitation Game. This presents, at the experience level, our difficulty in perceiving the machine underlying the embodiment of Mimo Stein [27]. The illusion of reality is at the same time an aesthetic narrative resource, and an ethical and moral framework.

The same happens with PoupinhaFootnote 4, a chatbot developed for scheduling in Poupatempo’s system. According to numbers submitted by its developers, of 14 million messages exchanged in 4 months, almost 70 thousand said “thank you” and “God bless you.” These behavioral observations show that some people who interacted with the chatbot did not notice they were talking to a machine. Kak believes that “even if machines do not become conscious, there will be a growing tendency for humans to consider them as if they are” [16].

Edgard’s concept, inspired by Nunes’s Mimo Stein [27], came to question and criticize AI technologies through a satiric, ironic discourse, and thoughts associated with the emergence of intelligent machines capable of dominating the world and enslaving humans. Edgard appears in the electronic age, which can be characterized [20] as immediate, since there is no delay between the expression of an idea and its reception; socially conscious, considering the large number of people who can view the same subject simultaneously; conversational, in the sense of being more interactive and less formal; collaborative because communication invites a response that becomes part of the message; and inter-textual, when the products of our culture reflect and influence each other.

The character is convinced that robots are better than humans. In the project, to approximate him to the HAL, of Clarke [29], flaws were included in his speech and performance. The conversational experience with Edgard proposes to ask ourselves: are the applications of AI superior to us humans? As a result of disinterested scientific researchFootnote 5, would their statements be true? In it could we find the contradictions as it does with homo sapiens and logical systems?

With the development of conversational technologies as an extension of communication, the possibility of writing as we speak involving the crude mechanics of writing, with all its economy, spontaneity and even vulgarity, creates a new type of conversational interaction [30]. In this new type of dialogue, it is necessary to remember that language, according to Everett [31], changes lives, builds societies, expresses our highest aspirations, our most basic thoughts, our emotions and our philosophies of life, and ultimately, is at the service of human interaction. Therefore, to create systems, such as Edgard, that use the natural interface to improve the user experience, digital interaction must not use screen scrolling, sliding or button clicks, but conversations [32].

3.1 Designer’s Control Over the Narrative Flow

The human response then becomes a factor of too much importance for media that seeks to produce an aesthetic experience in the narrative or conversational context. Plantinga [33] argues, using cinema as an example, that user responses go far beyond the appreciation of aesthetic factors and have value in psychology, culture, and ideology. It is in the interest of this project development to then consider the user’s reactions to the chatbot.

To better understand this aspect of the experience, digital games expertise has been a great help in enhancing the individual response control through Design. Games stand out for being interactive and continually dealing with the human factor, something that has only intensified as technology has become more complex.

“The main feature of most games is to turn traditional media into an interactive format that allows the player to take part actively. Movies or videos allow viewers to interact only passively, following the narrative and predicting possible conclusions, while games offer the player with interactive means to change the narrative’s course” [34].

But how is this done? It is true that the designer has no command over the player’s choices. However, these decisions can be influenced. This influence is subtle, delicate, ingenious and can be constructed on several, if not all, components used in the creation of a narrative. The elements of control over the interagency narrative flow include: limit narrative paths; set up clear goals to be achieved; explore the interface to intensify the immersion of the player; develop the appropriate visual design to the theme; direct the interactor’s look through the spatial and chromatic composition of the scenarios; compose characters and their personalities considering the emotional contexts objectified in the narrative; and the same goes for music and sound effects [36]. These concepts were essential to immerse the user in the world created for Edgard. Among them, there are:

-

Visual Design: Edgard’s style needs to resemble an antique computer, worn and dirty. It shows how long the machine has been abandoned.

-

Interface: The monitor reproduces an old terminal, from its color limit to the font used. Other elements, such as the text box and sweep lines, were made thinking about that time. A significant source of stimuli was the game “Komrad” [37], where the player interacts through conversation with a Soviet Union AI.

-

Character: The personality and construction of the chatbot narrative style are essential to create an experience that engages the user. As Edgard is an obsolete system with no maintenance, its language shows bugs and errors, alluding Clarke’s “HAL” [29].

The human being is used as the foundation regarding personality in a machine. From the emotion theories and observation of human behavior, one can conclude that these are crucial factors in decision making [14]. Emotions are inseparable and a necessary part of cognition. According to Norman [38], these change the way we think and are constant guides to individual conduct.

Affective Computing is a branch of computer science that considers emotions in the development of algorithms which can be another technological alternative in narrative construction, making the experience with Edgard more productive and enriching. According to Picard [39], affective computing is the computation that relates, arises from, or influences emotions. Affective computing allows a device to recognize the user’s mood by the voice tone, facial expression, among others. The movie “Her” [40] is an example of this analysis. In the film, Samantha, the protagonist’s computer operating system, synchronizes its action based on what is spoken and the tone used by the user. This situation is no longer unique to science fiction movies. Conversational agents such as Apple’s “Siri” and Amazon’s “Alexa” are developed with affective computing technology that involves complex sensing and information processing that lead to emotionally intense results.

Although we are not able to give machines emotions, we can say that humans treat computers as people, being observed by several experiments like those of Reeves and Nass [41], in 1996. In these experiments, people had to work on a computer with a dialogue-based training program. They were divided into two groups to evaluate the performance of the machine. One group had to answer the evaluation questions on the same computer that was used for the training while the other used a different workstation. People who had to answer questions on the same computer gave significantly more positive responses than others - that is, they were less honest and more cautious - which meant that they were more diplomatic in their assessment similar to what they would do while interacting with people. So if people build emotional attachments to machines, why not make the computer recognize those emotions or express them? Among the motivations considered to attribute emotions to Edgard are: providing feedback about how he feels about the environment; show how the robot is affected by people around it; demonstrate what kind of emotions he understands and how he is adapting to the ever-changing world around him [42]; and especially, make machines less frustrating to interact with [39] (Fig. 2).

4 Final Thoughts

Understanding AI technologies have led our research group to investigate a wide range of knowledge territories from philosophy to history, technology, and consciousness. In observing the contemporary scenario, one perceives a conflictive picture, gloomy perspectives align with other promising ones. What has been perceived during this period of investigation is that alternatives to this conundrum exists and are related to modern technologies. Some of these give rise to new insights, while others connect the XXI century to the knowledge and practices developed throughout the culture’s past. The history of Art and Design in this sense can be seen as a rich setting to explore.

The chatbot Edgard is a study of alternatives in new technologies. Through the use of AI for the development of this project and the results obtained, a critical view of conversational experiences’ potential through human-machine interactions becomes evident, providing new insights and guiding future chatbot projects. A diverse and creative look is an inevitability for the creation of coherent conversational interfaces involving users and narrative contexts in emotionally productive ways.

Authors such as Bostrom and Sandberg [43] discuss Cognitive Improvement, which seems to converge to the perspectives aligned here. For the authors, creativity and ethics are fundamental components in the conception of knowledge and culture in a harmonious future for humanity. The creative activities will be those that will support the expansion of human consciousness and the social transformations necessary to prepare us for the challenging struggles that are present today. For those authors, improvement in cognition has a wide range of possibilities because:

“Most efforts to improve cognition are rather mundane, and some have been practiced for thousands of years. The prime example is education and training where the goal is often to not only convey skills or specific information but also to improve general mental faculties such as concentration, memory, and thinking. Other forms of mental training, such as yoga, martial arts, meditation and creativity courses are also in common usage” [43].

In this sense, access to knowledge and its practical use, mediated by the use of technological devices, across its spectrum - from levers to smartphones - can integrate into creative production, such as the conversational system presented here, and the extraordinary mental states [9]. The idea of “Flow” [44], linked to aesthetic experience [45], and altered states of consciousness described in Buddhism and Taoism is already present in conceptual and design construction, in the field of Experience Design (UX). In this same direction, Hughes [46] considers creative states of mind as inherently “non-normal,” since the creative act results from expanded consciousness, made up by “unconscious processes being used in the unification of opposites in a new synthesis” [46]. In reflecting on creativity and the information revolution, the author recalls William Gibson’s novel “Neuromancer,” [47] where he predicts the power of the Internet to produce “consensual hallucinations.” Edgard puts himself in a similar approach to this perspective by allowing an interactive process to establish itself in the human-machine dialogue toward a creative activity capable of assigning new meanings to an experience.

Notes

- 1.

Abbreviation for the Group of Twenty, a forum which is made up for the governments and central bank governors of the 19 largest economies in the world and the European Union.

- 2.

KPMG is a professional services company and one of the top four auditors, with Deloitte, Ernst & Young (EY) and PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). Headquartered in Amstelveen, Netherlands, KPMG employs 189,000 people and offers three lines of services: financial, tax and advisory audit. Its tax and consulting services are divided into several service groups. The name “KPMG” means “Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler,” and it was chosen when KMG (Klynveld Main Goerdeler) fused with Peat Marwick in 1987.

- 3.

A concept that characterizes where games take place. It presents itself isolated and sacred, where the player must respect certain rules, otherwise, he is a spoilsport. The magic circle is an imaginary space within the real world established by the game limits [25].

- 4.

Poupinha is the virtual attendant (chatbot) of Poupatempo. Poupatempo a Brazilian program that brings together agencies and companies that offer public services, performing non-discriminatory service or privileges with efficiency and courtesy. The system integrates self-service, fixed stations, mobile stations. Available at: https://www.messenger.com/t/PoupinhaSP.

- 5.

The concept of disinterested scientific research relates to Lyotard’s skeptical views regarding modern cultural thoughts. In his book: La Condition postmoderne: Rapport sur le savoir (The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge) [35], Lyotard argues that the loss of faith in meta-narratives affects how we view science, art, and literature, as we are now opting for little narratives. As meta-narratives fade, science undergoes a loss of faith in its search for truth having to find alternative means to legitimate its efforts.

References

Cupani, A.: A tecnologia como problema filosófico: três enfoques. Scientiae Studia 2(4), 493–518 (2004)

Schmidek, H.C.M.V., et al.: Dependência de internet e transtorno de déficit de atenção com hiperatividade (TDAH): Revisão Integrativa. J. Bras. Psiquiatr. 67(2), 126–134 (2018)

Simondon, G.: On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects. Aubier, Paris (2011)

Lopes, W.E.S.: Gilbert Simondon e uma filosofia biológica da técnica. Sci. Stud. 13(2), 307–334 (2015)

Simondon, G.: Imaginación e Invención. Cactus, Buenos Aires (2013)

Camolezi, M.: On the concept of invention in Gilbert Simondon. Sci. Stud. 13(2), 439–448 (2015)

Duchamp, M.: A Fonte, Porcelana, 23,5 × 18 cm, altura 60 cm. http://artenarede.com.br/blog/index.php/tag/marcel-duchamp/

Kac, E.: GFP bunny: a coelhinha transgênica. Galáxia. Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação e Semiótica (2007). ISSN 1982-25533

Harari, Y.N.: Homo Deus: uma breve história do amanhã. Editora Companhia das Letras (2016)

Kurzweil, R.: How to Create a Mind: The Secret of Human Thought Revealed. Penguin, New York (2013)

Twomey, P.: Toward a G20 Framework for Artificial Intelligence in the Workplace (2018). https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/documents/Paper%20No.178.pdf. Accessed 23 Dec 2018

KPMG (Holand): Rise of the humans: the integration of digital and human labor. KPMG, Amstelveen (2016). https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2018/08/rise-of-the-humans-the-integration-of-human-and-digital-labor.html. Accessed 23 Dec 2018

Eubanks, V.: Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. St. Martin’s Press, New York (2018)

Damasio, A.: Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain. Vintage, New York (2012)

Wilson, R.A., Keil, F.C. (eds.): The MIT Encyclopedia of the Cognitive Sciences. MIT Press, Cambridge (2001)

Kak, S.: Artificial Intelligence, Consciousness and the Self. Medium (2018). https://medium.com/@subhashkak1/artificial-intelligence-and-consciousness-6b5ff2e5b5a. Accessed 23 Dec 2018

Dewey, J.: Arte Como Experiência. Martins Fontes, São Paulo (2010)

Shannon, B.: The Antipode of the Mind: Charting the Phenomenology of the Ayahuasca Experience. Oxford University Press, New York (2002)

Riedl, M.O., Bulitko, V.: Interactive narrative: an intelligent systems approach. AI Mag. 34(1), 67–77 (2013)

Hall, E.: Conversational Design. A Book Apart. New York (2018)

Curry, C., O’Shea, J.D.: The implementation of a story telling chatbot. Adv. Smart Syst. Res. 1(1), 45 (2012)

Cavazza, M., Charles, F.: Dialogue Generation in Character-based Interactive Storytelling. AIIDE (2005)

Bremond, C.: Logique du récit (1973)

Studio, Night School. Oxenfree. Glendale, CA. Microsoft Windows; macOS; Xbox One; PlayStation 4; Nintendo Switch; Linux; iOS; Android. 4680685 (2016)

Huizinga, J.: Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Routledge, London (1949)

Dale, R.: The Return of the Chatbots. Cambridge University Press (CUP), Cambridge (2016)

Nunes, F.O.: Mentira de artista: arte (e tecnologia) nos engana para repensarmos o mundo. Cosmogonias Elétricas, São Paulo (2016)

Weizenbaum, J.: ELIZA—a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. Commun. ACM 9(1), 36–45 (1966)

Clarke, A.C.: 2001: A Space Odyssey. Penguin, New York (2016)

Mcwhorter, J.: Is Texting Killing the English Language? https://www.ted.com/talks/john_mcwhorter_txtng_is_killing_language_jk#t-380477. Accessed 26 May 2018

Everett, D.: How Language Began: The Story of Humanity’s Greatest Invention. W. W. Norton, New York (2017)

Følstad, A., Brandtzæg, P.B.: Chatbots and the new world of HCI. Interactions 24(4), 38–42 (2017)

Plantinga, C.: Moving Viewers: American Film and the Spectator’s Experience. University of California Press, California (2009)

Zillman, D., Vorderer, P.: The Psychology of Its Appeal. Routledge, Abingdon-on-Thames (2000)

Lyotard, J.F.: La Condition Postmoderne, Rapport Sur Le Savoir, 1st edn. Minuit, Paris (1994)

Schell, J.: The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses, 1st edn. CRC Press, Florida (2008)

Sentient Play: Komrad. iOS; watchOS (2016)

Norman, D.A.: Emotional Desing: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things. Basic Books, Nova York (2004)

Picard, R.: Affective Computing, vol. 16, p. 321, Cambridge (1997). https://affect.media.mit.edu/pdfs/95.picard.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct 2018

HER. Direção de Spike Jonze. Produção de Megan Ellison, Spike Jonze e Samantha Morton. Warner Bros. Pictures, Los Angeles (2014). (126 min.), Netflix, son., color. Legendado

Reeves, B., Nass, C.: The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1996)

Azeem, M.M., Iqbal, J., Toivanen, P., Samad, A.: Emotions in Robots. In: Chowdhry, B.S., Shaikh, F.K., Hussain, D.M.A., Uqaili, M.A. (eds.) IMTIC 2012. CCIS, vol. 281, pp. 144–153. Springer, Heidelberg (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-28962-0_15

Bostrom, N., Sandberg, A.: Cognitive enhancement: methods, ethics, regulatory challenges. Sci. Eng. Ethics 15(3), 311–341 (2009)

Csikszentmihalyi, M.: Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. HarperCollins, New York (2008). e-Books

Marković, S.: Components of aesthetic experience: aesthetic fascination, aesthetic appraisal, and aesthetic emotion. I-Perception 3(1), 1–17 (2012)

Hughes, J.: Altered States: Creativity Under the Influence. Watson-Guptill Publications, New York (1999)

Gibson, W.: Neuromancer, vol. 1. Aleph, São Paulo (2008)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Fogliano, F., Fabbrini, F., Souza, A., Fidélio, G., Machado, J., Sarra, R. (2019). Edgard, the Chatbot: Questioning Ethics in the Usage of Artificial Intelligence Through Interaction Design and Electronic Literature. In: Duffy, V. (eds) Digital Human Modeling and Applications in Health, Safety, Ergonomics and Risk Management. Healthcare Applications. HCII 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 11582. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22219-2_25

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22219-2_25

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-22218-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-22219-2

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)