Abstract

International nuclear safeguards inspectors visit nuclear facilities to assess their compliance with international nonproliferation agreements. Inspectors note whether anything unusual is happening in the facility that might indicate the diversion or misuse of nuclear materials, or anything that changed since the last inspection. They must complete inspections under restrictions imposed by their hosts, regarding both their use of technology or equipment and time allotted. Moreover, because inspections are sometimes completed by different teams months apart, it is crucial that their notes accurately facilitate change detection across a delay. The current study addressed these issues by investigating how note-taking methods (e.g., digital camera, hand-written notes, or their combination) impacted memory in a delayed recall test of a complex visual array. Participants studied four arrays of abstract shapes and industrial objects using a different note-taking method for each, then returned 48–72 h later to complete a memory test using their notes to identify objects changed (e.g., location, material, orientation). Accuracy was highest for both conditions using a camera, followed by hand-written notes alone, and all were better than having no aid. Although the camera-only condition benefitted study times, this benefit was not observed at test, suggesting drawbacks to using just a camera to aid recall. Change type interacted with note-taking method; although certain changes were overall more difficult, the note-taking method used helped mitigate these deficits in performance. Finally, elaborative hand-written notes produced better performance than simple ones, suggesting strategies for individual note-takers to maximize their efficacy in the absence of a digital aid.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

International nuclear safeguards are activities or agreements that provide assurance to the global community that States are using their nuclear technologies for peaceful purposes. International safeguards are designed to detect: the diversion of nuclear material from safeguarded facilities, the misuse of safeguarded facilities for undeclared nuclear purposes, and the development of undeclared facilities for undeclared nuclear purposes. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is the agency tasked with verifying safeguards for those countries that have signed safeguards agreements. Verification of these safeguards is achieved by sending inspectors to a facility to perform a variety of inspection tasks, including: verifying the integrity of seals placed on monitored items, taking material measurements, and looking for anomalies in a facility that may be indicative of misuse. Inspectors are often limited in the types of note-taking activities they can perform during an inspection (details below), and often face large time delays between the time of inspection and retrieval of the information recorded, either for briefings to team members or return visits to the facility.

As such, IAEA inspectors face a unique set of cognitive and information processing challenges in the recording and transfer of information garnered from field inspections that have not been adequately addressed by extant research literature. In this paper, we describe the cognitive nature of the note-taking tasks performed by inspectors, then note the gaps in the literature on knowledge transfer in a shift-work environment as well as the cognitive science of note-taking. Finally, we detail an empirical study aimed at addressing these gaps, in order to produce recommendations for best practices for note-taking during inspections that will maximize knowledge transfer in IAEA inspectors.

1.1 IAEA Inspection Activities

Specific activities performed by IAEA inspectors range in complexity from relatively straightforward (e.g., checking seal numbers on containers of nuclear materials against lists of seals that should be present; see [1]) to more cognitively complex (e.g., keeping track of their physical location within the facility to verify facility layout is as declared). In addition to completing their circumscribed list of inspection tasks, inspectors must also maintain situational awareness regarding the environment, and make note of anything unusual going on in the facility and/or anything that changed since the last facility visit. This means that inspection notes must be complete enough to enable effective change detection across time delays that could range from several weeks to several months in duration. Moreover, different inspection teams may visit the same facility across time, and so the recorded notes must be thorough enough to transfer this information across people.

The ability to take thorough notes during an inspection is often limited by constraints placed on inspectors during visits. For example, inspectors are often limited by the types of materials they can bring into or take out of the facility. They are always allowed to make notes with pen and paper, but on some occasions, they may be allowed to bring in a digital camera or request for their host to take digital photos that can be transferred to headquarters. Inspectors must often complete their visits in a restricted amount of time because their visits typically require that all facility activities are halted, creating time pressure to complete their activities quickly. These real-world constraints create a complex operational environment in which inspectors must perform high consequence inspection tasks.

1.2 Knowledge Transfer in Shift Work

Knowledge transfer refers to the sharing of knowledge, information, and experiences between people within an organization, and provides a way to capture and maintain records of institutional knowledge accumulated over time [2]. Anytime knowledge is handed off between teams, there is a risk for loss of continuity of knowledge if the handoff is not carried out effectively. As such, much research exists that asks how to effectively transfer knowledge across teams, the bulk of which focuses on the immediate transfer of knowledge been shift workers in a variety of environments, including production [3], medical environments [4], off-shore drilling [5], and nuclear power plants [6]. Enabling more effective knowledge transfer across shifts of workers can more effectively build institutional knowledge, keeping multiple independent groups of workers from trying to independently solve the same problem. More importantly, shift handoffs have been shown to increase the likelihood of accidents [5, 7] and medical errors [8], and so creating better knowledge transfer protocols can lower the risk of potentially life-threatening situations.

Several components of a successful shift handoff have been identified across diverse environments [5,6,7]. First, face-to-face handoffs have been shown to help establish a shared mental model between incoming and outgoing operators. Successful handoffs are structured and consistent to ensure that information is not missed, and have well-established expectations about the types of information to report, which relate directly to the goals of the task to be performed. Finally, operators should be given as much time as possible to prepare for and conduct handoffs. Several types of high-risk handoffs have been identified that might require even more time or preparation in order to reduce the risk of errors, which include handoffs between experienced and inexperienced operators, as well as those that occur after a long break away from work.

Unfortunately, many of these recommendations cannot be implemented in the case of IAEA safeguards inspectors. For example, although handoffs between inspectors may take place in person, they often take place at IAEA headquarters before facility visits occur. As such, when inspectors access information about previous facility visits while in the field, they must rely extensively on one-way written communications instead of the preferred face-to-face communications. Inspectors are often time-limited while on facility inspections, and so the recommendation that operators are given as much time as possible to prepare for handoffs cannot be implemented. The recommendation that handoffs are clearly structured is not always possible, because inspectors do not have control over the types of note-taking materials they are allowed to carry into the facilities they inspect. Finally, handoffs regarding specific facilities typically occur after a long break away from the facility, which qualifies IAEA inspector handoffs as high-risk.

In the absence of a face-to-face handoff, transfer of knowledge can also occur via boundary objects, which are artifacts that can span the boundary between two distinct groups of workers and can serve as a formalized way to codify relevant knowledge to share between the two groups [9, 10]. In our case, the boundary exists between the inspectors who performed the original inspection and those performing the return inspection, and the notes taken during the original inspection serve as the boundary objects. Although empirical research suggests that knowledge transfer is most successful when the creation of boundary objects is supported by the organization’s culture, and when boundary objects are freely available to all workers [3], there is little research into the specific features that boundary objects should contain in order to be effective. As such, one goal of the current study is to identify how IAEA inspectors can create effective boundary objects that will enable the effective and efficient transfer of knowledge to different inspectors across a time delay.

1.3 Cognitive Science of Note-Taking

Research from both the educational psychology literature on note-taking as well as the cognitive psychology literature on memory may be relevant to our question of how to create boundary objects to enable effective and efficient knowledge transfer. These concepts will be reviewed in turn below.

Educational Psychology.

The field of educational psychology has a long history on the study of note-taking efficacy for learning and achievement in academic settings (for reviews, see [11, 12]). From this literature, it has been shown that note-taking generally improves students’ academic achievement by benefiting two memory processes: encoding (i.e., enables creation of stronger memory traces at the time of study) and external storage (i.e., enables recall of forgotten information and forming of new connections between concepts during review of notes). However, the bulk of this previous work has focused on classroom settings, in which participants take notes on lectures and are later tested on their memory of the factual and conceptual information presented during the lecture. Some work has examined note-taking strategies outside of the classroom (for reviews, see [13, 14]), although these have also tended to focus on heavily verbal areas, such as note-taking during boardroom meetings, courtroom procedures, or counseling sessions.

Recent work looking at the integration of technology into the classroom may apply to the current question of how to integrate digital recording technologies into inspector note-taking. Mueller and Oppenheimer [15] investigated how laptop use impacted memory for information presented in a lecture. They found that taking notes via laptop resulted in lower memory performance on conceptual questions relative to taking notes by hand, although no differences were found between the two note-taking strategies for factual questions. They postulated that this was because laptops allowed students to record more content from the lecture than writing notes by hand, resulting in a near-verbatim record of the lecture, whereas taking hand-written notes forced students to consolidate concepts before writing them down.

The educational psychology literature on note-taking fails to adequately address the needs of inspectors, namely, how to capture complex visuo-spatial information during facility visits. However, Mueller and Oppenheimer’s [15] findings regarding the potential drawbacks of using technology for note-taking may apply, as the current study will investigate whether a similar over-reliance on verbatim capture rather than consolidation of information may be observed when digital cameras are used in note-taking.

Cognitive Psychology.

There are also several principles that can be drawn from the cognitive psychology literature on learning and memory that could come into play to evaluate what features might make effective notes. One such concept, the dual-coding theory, posits that verbal and visual (and other nonverbal) information are processed through separate channels in associative memory (for review, see [16]). Work in this domain has shown that concepts that are represented via both verbal and nonverbal associations will be remembered better than those encoded with only one or the other [17] due to the enhanced processing afforded by the dual-channel encoding. Another relevant concept from the memory literature is that of levels of processing [18, 19], which has shown that words that are encoded at a “deeper” level of processing, such as focusing on the semantic meaning of the term, are remembered better than words encoded with a shallower level of processing, such as focusing on its surface characteristics (e.g., case).

Recent work found what has been dubbed the drawing effect, in which words that were studied by drawing a picture of the object described by the word were remembered better at test than words that were studied by simply writing the word down [20]. This finding held even when controlling for effects of elaboration, as writing a list of the object’s visual features was less beneficial to memory than drawing a picture of the item. These results support the dual-coding framework, because the words that were drawn at study would have both a verbal and visual memory cue, thus strengthening their memory trace, whereas words that were only written would only have been encoded via the verbal channel.

One limitation of the memory literature in its applicability to the current question is that most memory research uses either lists of words or declarative facts for stimuli, and tends to use short retention intervals (i.e., a few minutes) between study and test. There is thus a clear gap in this literature regarding how to best record information about complex non-verbal stimuli (e.g., facility layout, visual characteristics of a room full of containers) to best enable the transfer of that knowledge either to oneself during a future inspection, or to an entirely different inspector, with a time delay of several months to a year.

1.4 The Current Study

The current study addressed the gaps in the literatures on knowledge transfer and the cognitive science of note-taking, to better understand how these techniques can be applied in a safeguards-relevant environment. We compared the efficacy of different note-taking methods for knowledge transfer on a change detection task after a time delay. In the current study, participants studied four arrays of complex images, and were limited to the types of notes they could take for each array: digital camera only, hand-written notes only, digital camera and hand-written notes, or no aid. Participants were allowed to choose their own strategies for the creation of their hand-written notes—e.g., text-based notes describing the images in prose, visually-based drawing of the images, or some combination—as well as for taking photos of the display, provided that they did not take a photograph that encompassed the entire array simultaneously. They then returned approximately two days later to complete a memory task on the image arrays, during which they could use the notes they took at study. Objects in the array could undergo several types of changes: material, orientation, location within the array, or replacement by a different object, although any one object only underwent a single change (e.g., and object would not change location and orientation).

Our experimental questions of interest were as follows. First, what is the most effective note-taking method for the transfer complex visual knowledge? To answer this question, we investigated how change detection accuracy differed across study conditions, change types, and individual note-taking strategies. Secondly, how does note-taking method impact confidence in one’s decision? Given that inspectors do not know the ground truth when recording observations during inspections, it is important to understand the subjective impressions of their efficacy across different note-taking strategies. This could ensure that inspectors come away with a realistic estimation of their efficacy so that they do not unnecessarily trigger additional inspection activities erroneously. Finally, do certain note-taking methods enable more efficient knowledge transfer, as measured by the time to complete the study and test sessions? Given the time restrictions on most safeguards inspections, the amount of time needed to effectively use each note-taking strategy is an important practical consideration.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

Twenty-one participants participated in the study. One participant was excluded due to experimenter error in administering the experimental materials, leaving twenty participants in the final data set (seven females). Mean age was 44 (range: 24–68). All procedures were approved by the Sandia National Laboratories Human Studies Board, and participants gave their informed consent before the session began.

2.2 Materials

Study Images.

Materials consisted of computer-generated images of novel industrial looking objects (e.g., antennae, widgets, gears, etc.; see Fig. 1), which were originally created for a machine learning evaluation task. Each object had a baseline image of a default surface material and orientation that could undergo various changes, including changes in lighting, orientation, or surface material properties such as texture. Four different study boards were created, each of which consisted of 40 initial images, for a total of 160 initial images. For the test, 20 items per board were replaced with a different image: four material changes, depicting the same object in the same orientation but with a different surface material; four orientation changes, depicting the same object made of the same material but in a different orientation; six object changes, depicting a totally different object; and, six location changes, in which six original objects rotated locations on the board. This created a total of 56 replacement images, for a total of 216 unique images in the experiment.

Demographics Questionnaire.

Participants optionally completed a demographics questionnaire, in which they reported their gender, age, highest degree earned, and whether they had any prior visual search experience, either professionally (e.g., x-ray operator) or non-professionally (e.g., birding, video gaming).

2.3 Procedure

Study Session.

Each study session began with an overview of the experimental procedure for both the study and test sessions. Participants were instructed that in the study session, their task was to learn the layout and characteristics of several sets of images presented on boards, using one of the note-taking methods allowed. They were also told that when they returned at test, they would be tested on their memory for the image layouts, and that they would be able to use the notes they took at study to help with this task. Participants were not informed of the types of changes they would be looking for at test.

Instructions for the individual note-taking conditions in the study session were as follows. In the camera only condition, participants were told: “You can take photos of the board with the digital camera provided. The only restriction is that you can’t take a picture that includes the entire board, but you can take pictures of the individual items, or groups of items together.” In the notes only condition, participants were told: “You can take notes in this notebook to help yourself remember the layout of the images. You can use any combination of words or pictures.” In the camera + notes condition, participants were told: “You can take photos of the board with the digital camera provided (with the restriction that you can’t take a picture that includes the entire board). You can also take notes in the notebook to help yourself remember anything about the layout of the images, or your strategy while taking the pictures.” In the no aid condition, participants were told: “For this board, you can only rely on your own memory; you cannot take notes in any way.” Participants were allowed to ask questions before the study session began.

The order of note-taking condition was counter-balanced across participants using an incomplete Latin Square design, creating four lists, each with a different order of study conditions. This ensured that each study condition appeared in each ordinal position once and that each study condition followed each other study condition once, to control for order effects. The order of presentation of the four study boards was held constant across participants, while the note-taking condition was counter-balanced as described above, ensuring that each set of images was studied equally often using each note-taking method across participants. Separate one-way between-subjects Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) conducted on the accuracy data confirmed that there were no effects of list (F(3,16) = .35, p = .79) nor study board (F(3,57) = 0.85, p = .48); as such, these counterbalancing factors will not be included in analyses.

Participants were allowed a maximum of 12 min per study condition, although they were allowed to finish earlier if desired, and the length of time taken per study board (in seconds) was recorded by the experimenter. After all four study conditions were completed, participants completed the demographics questionnaire and were provided with a debriefing form. The experimental session lasted no longer than one hour.

Test Session.

At the start of the test session, participants were informed that they would be tested on their memory of the image layouts that were studied during the test phase. For each test board, participants were given an 8 × 5 grid (on a standard 8.5″ × 11″ piece of paper), with one square per item on the board and two questions per item: (1) Did the item change? (Y/N), and (2) Are you sure? (Y/N). For each image, participants were instructed to indicate: (1) whether it changed or not (by circling “Y” or “N,” respectively), (2) whether they were sure of their choice or not (again, by circling “Y” or “N,” respectively), and (3) if they reported a change, the nature of the change (via open-ended response). Participants were shown a table that demonstrated an example of each of the four possible change types: material, orientation, location, or replacement. They were allowed to refer to this table during the test session. Participants were also allowed to refer to the notes and/or digital images that they took for each board during the study session. Test boards were viewed in the same order that they were studied. Participants were allowed a maximum of 12 min to complete each board, although they could choose to take less time if desired, and the time to complete each board (in seconds) was recorded by the experimenter.

Scoring.

Participants received multiple scores per item. Overall accuracy was converted to binary data, in which participants received a score of 1 if they answered correctly as to whether or not the item changed, and a 0 if they answered incorrectly. For change type accuracy, participants received a score of 1 if they correctly identified the change type, a score of .5 if they responded “object” change to a location change (because a location change could be misinterpreted as an object change if only the object’s original location was considered and the participant failed to see where on the board the object moved to) or for a small number of objects to which multiple participants made the same error (e.g., if an orientation change made the object look so different such that multiple participants mistook it for a new object), and a score of 0 if they reported the incorrect change type. The confidence data was also converted to a numeric value, where a “yes” response was scored as a 1 and a “no” response was scored as 0.

3 Results

3.1 Recognition Performance by Study Condition and Change Type

To answer our main experimental question of whether study condition and item change type interacted to impact accuracy, we calculated the d’ statistic. The d’ statistic is a measure of target discriminability, which compares the proportion of true hits and false alarms to measure a participant’s ability to accurately discriminate targets (i.e., items that changed) from non-targets (i.e., items that did not change). Larger d’ values indicated that a subject frequently responded “change” to changed items and very rarely to non-changed items, and thus were able to successfully discriminate targets from non-targets. Conversely, lower d’ values indicated that subjects frequently responded “no change” to changed items and/or “change” to non-changed items, and thus were unable to discriminate targets from non-targets. The d’ scores were calculated separately for each participant for each combination of study condition and item change type, by comparing the hit rate for each change type relative to the false alarm rate for the non-changed items within that study condition.

Scores were analyzed using a two-way within-subjects ANOVA, with the factors of study condition (4: camera only, camera + notes, notes only, and no aid) and change type (4: location, material, object, and orientation). Results showed main effect of study condition (F(3,57) = 43.19, p < .05) and change type (F(3,57) = 24.35, p < .05), as well as a significant interaction (F(9,171) = 8.04, p < .05). Means for each condition are shown in Fig. 2. The main effect of study condition indicated that, in general, the camera only and camera + notes conditions had the highest d’ scores across all change conditions, followed by the notes only condition, and finally, the no aid condition. The main effect of change type reflected the fact that d’ was highest for location and object changes, followed by orientation changes, with material changes showing the lowest overall d’ scores. However, both of these main effects were qualified by their significant two-way interaction.

Given the significant interaction, follow-up t-tests were conducted to compare the study conditions within each change type, to understand whether some study methods produced better knowledge transfer for certain changes. All pairwise t-tests were conducted using the Holm correction to control the family-wise Type I error rate [21], implemented by use of the “p.adjust” command in the R statistical computing environment [22]. Across all four change types, the camera only and camera + notes conditions had significantly higher d’ than both the notes only and no aid conditions (all t(19) > |3.66|, p < .05) but did not differ from one another (all t(19) < |1.06|, p > .30). However, the notes only condition showed significantly higher d’ than the no aid condition for location and object changes (all t(19) > |2.75|, p < .05), but did not differ from the no aid condition for either material or orientation changes (all t(19) < |1.54|, p > .28). This finding suggests that hand-written notes alone were better than no study aid in transferring gross information about the image array, like the identity and overall layout of objects, but were not effective for conveying more subtle changes, like the object’s material or orientation.

3.2 Effects of Note-Taking Strategy

In the camera + notes and notes only conditions, participants were free to choose their strategy for taking hand-written notes. We will explore the hypothesis that their self-selected note-taking strategy may have impacted their d’ scores across change types.

Camera + Notes Condition.

For this analysis, we started by binning participants into categories based on the type of hand-written notes they took. These categories included various combinations of photo layout descriptions (i.e., a diagram of which images in the display each photo captured), verbal descriptions of the objects, and hand-drawn pictures of the objects. Table 1 lists the number of participants who self-selected into each note-taking strategy, as well as the average d’ for each group. There was no significant effect of note type within the camera + notes condition (F(6,13) = 0.33, p = .91). However, there was a trend such that participants who recorded multiple types of information in their notes (e.g., photo layout + verbal description) performed better than participants who recorded only a single information type.

Notes Only Condition.

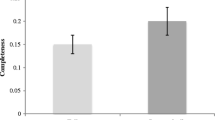

Participants’ note-taking strategies in the notes-only condition were binned into three categories: combined hand-drawn pictures and verbal descriptions of the images, hand-drawn pictures only, and verbal descriptions of the objects only. We conducted an exploratory analysis to assess whether d’ scores differed across these note-taking conditions. A one-way between-subjects ANOVA revealed a significant effect of note type (F(2,17) = 3.91, p < .05). As can be seen in Fig. 3, this effect reflected the fact that d’ scores were highest for participants whose notes combined drawings and verbal information, followed by drawings only, with verbal notes alone producing the lowest d’ scores. This suggests that taking more elaborative notes that included information across both verbal and visual channels (i.e., both drawing pictures and writing verbal descriptions) led to better recall than only using a single type of encoding (i.e., either drawings or verbal descriptions).

3.3 Change Type Accuracy

We next asked whether accuracy for identifying an item’s change type differed across study conditions. This analysis only included data for items that changed and for which the participant correctly reported that a change took place, which comprised 1129 total observations (35% of the original dataset). One participant was excluded from this analysis due to a failure to answer any change items correctly in one condition. Change accuracy data was submitted to a one-way within-subjects ANOVA with the factor of study condition, which revealed a significant main effect of study condition (F(3,54) = 12.55, p < .05). Mean values are shown in Fig. 4. Follow-up t-tests tested all pairwise comparisons, to ask which conditions differed from each other in terms of correctly identifying the type of change. Accuracy was numerically highest for the camera + notes condition, which differed significantly from the notes only and no aid conditions (all t(18) > |4.66|, p < .05), but not from the camera only condition (t(18) = .98, p = .34). The camera only condition also did not differ from the notes only condition (t(18) = 1.61, p = .25), although it was significantly better than the no aid condition (t(18) = 3.97, p < .05). Finally, the notes only condition was significantly better than the no aid condition (t(18) = 2.83, p < .05). This pattern of findings suggests that the use of both hand-written and digital notes provided the greatest benefit in terms of transferring information about the type of change an item underwent (especially compared to notes alone), while the camera only and notes only conditions were not statistically different from each other.

3.4 Confidence

Participants reported whether or not they were sure of their answer for each item; this response was converted to a numeric value (Sure = 1, Not Sure = 0) and averaged for each participant in each study condition (see Table 2). To investigate whether confidence differed across study conditions, we submitted this data to a one-way within-subjects ANOVA with the factor of study condition, which found a significant effect (F(3,57) = 54.67, p < .05). Follow-up t-tests found that all conditions differed from one another (all t(19) > |4.13|, p < .05), except for camera only and camera + notes which were statistically indistinguishable (t(19) = −.25, p = .81). This finding shows the same pattern as overall d’ scores did, indicating that participants had relatively good metacognition insofar as recognizing that their memory was best in the camera only and camera + notes conditions.

In an exploratory analysis, we asked whether confidence differed across different accuracy types across study conditions—that is, whether confidence differed for hits, correct rejections, false alarms, or misses. As seen in Fig. 5, confidence levels for hits were very similar for the three note-taking conditions (although slightly lower for the notes only condition). Confidence for correct rejections dropped for the notes only condition, indicating that using a camera enabled participants to more confidently say when no change had occurred. However, confidence for misses dropped substantially for the notes only condition, but remained high for the camera only and camera + notes conditions. This pattern suggests that using the camera as a study aid, with or without additional notes, may have over-inflated confidence levels, particularly when participants incorrectly reported that no change was present. Although this analysis was just exploratory and no statistics were run due to unbalanced numbers of observations across conditions (e.g., some participants had no false alarms or misses in the camera only or camera + notes conditions), it suggests potentially detrimental effects of using a camera as a study aid.

3.5 Response Times

Next, we examined whether the time that participants took either at study or at test differed by study condition. Recall that both study and test times were capped at 12 min (or 720 s), but participants could choose to take less time if desired.

Study Time.

Across the four study conditions, study times were longest in the notes only condition, followed by the no aid condition, camera + notes, and finally the camera only condition (see Fig. 6). A one-way within-subjects ANOVA with the factor of study condition found a significant effect of condition, F(3,57) = 28.50, p < .05. Follow-up t-tests comparing each condition to each other showed that all conditions differed significantly from each other (all t(19) > |3.19|, p < .05), except for camera + notes and the no aid comparison (t(19) = 0.89, p = 0.38). The camera + notes took longer than the camera only condition, but did not produce any general benefits to knowledge transfer beyond a numerically higher ability to correctly detect an item’s change type.

Test Time.

Across the four conditions, test times were longest for the camera + notes condition, followed by camera only, notes only, and finally, the no aid condition (see Fig. 7). A one-way within-subjects ANOVA with the factor of study condition revealed a significant effect of condition, F(3,57) = 5.28, p < .05. Follow-up t-tests of all pairwise comparisons found that the only significant difference was between the camera + notes and no aid conditions (t(19) = −3.65, p < .05). There were, however, marginal differences between the camera + notes and the notes only conditions (t(19) = −2.49, p = .09), as well as between the camera only and no aid conditions (t(19) = −2.65, p = .08). Interestingly, the large benefit in study times observed for the camera only condition was not observed at test, suggesting that any benefits this condition may have conferred in ease of note-taking at study may have been washed out by the difficulty of accessing and using photos at test.

4 Discussion

4.1 Experimental Findings

The current study tested the efficacy of different note-taking methods that may be available to IAEA safeguards inspectors to enable knowledge transfer about a complex visual array. Our goal was to fill gaps in the literature on both knowledge transfer methods and the cognitive science of note-taking to make recommendations to inspectors on how best to utilize available note-taking methods to create boundary objects that enable effective and efficient knowledge transfer across a time delay.

Results showed that overall, the camera only and camera + notes study conditions produced the highest levels of knowledge transfer, as evidenced by their high d’ scores, which did not differ from each other in any comparison. The notes only condition was better than the no aid condition at transferring knowledge about gross changes in the layout of images and enabled participants to notice object and location changes better, but no differences were observed between the two conditions for relaying the more subtle material and orientation changes.

When participants were only allowed to make hand-written notes, we observed a relationship between a participant’s note-taking strategy and d’ scores, such that participants who used more elaborative, dual-channel encoding strategies for their written notes (i.e., used drawings and verbal descriptions) had the highest d’ scores, relative to participants who only made drawings or verbal descriptions. However, this comparison was made on a post-hoc basis, and could have been driven either by the elaboration effect at encoding [12] or increased ease of recall at test [11]. Regardless, it suggests that in situations in which hand-written notes are the only available study tool, recording the information in multiple ways (i.e., both visually and verbally) may be most beneficial to knowledge transfer, replicating findings from the basic memory literature in support of the dual-coding theory [16, 17].

Next, we considered what factors impacted a participant’s ability to correctly detect the type of change an item underwent. In this analysis, the camera + notes condition had the numerically highest performance and was significantly higher than the notes only condition (neither of which differed from the camera only condition). This finding provided weak evidence that the camera + notes condition may have produced the best change-type accuracy, and moreover, highlighted a potential drawback of the camera only condition. One mechanism that may help explain this trend could be participant’s over-reliance on the verbatim capture of images in the camera only condition, instead of taking the time to more deeply process and consolidate the information into their own words in order to make a hand-written note about it, as was required by both the camera + notes and the notes only conditions. This finding is similar to the over-reliance on verbatim capture when students take lecture notes on a laptop versus by hand, as observed by Mueller and Oppenheimer [15], and points to a more general drawback of technology usage in note-taking.

Unsurprisingly, the confidence data revealed that participants were most confident in their choices in the camera only and camera + notes conditions, less so in the notes only condition, and least confident in the no aid condition. However, exploratory findings showed that the use of a digital camera may have caused participants to be over-confident on incorrect trials, especially those in which they missed a change that was present.

Finally, when study and test times were considered, we found that the camera only condition had the shortest study times, but that this benefit was not present for test times. In other words, even though taking notes with the camera only was much faster than for the camera + notes condition, using the digital camera alone did not save people time at test. Anecdotally, participants often complained aloud about the difficulty of using the digital camera at test, and many appeared to struggle with the device. As such, the benefits of the camera only condition may have been outweighed by the difficulty of using the camera alone at test.

4.2 Recommendations for the Safeguards Domain

Based on our experimental findings, we would recommend that safeguards inspectors utilize a digital camera to take photos during inspections, if the option is available to do so. However, if time allows, we would recommend that inspectors make hand-written notes as well. This recommendation is based on the findings that the camera + notes condition provided at least a numeric benefit for identifying the type of change that took place relative to the camera only condition (and was significantly better than notes alone), produced test times that were equal to the camera only condition, and anecdotally reduced participant frustration at test. It is important to note that although the camera only condition elicited the shortest study times in the current experiment, the use of a camera may actually increase inspection time in the field, due to the need to obtain review and approval of photos taken in the facility.

Although no significant differences were observed in the efficacy of the type of hand-written notes that accompanied digital photos, trends in our data suggested the most effective notes both encoded information about the photo layout and elaborated on the images in some way, either through verbal descriptions or drawings. However, inspectors using a digital camera should be warned that they may be over-confident in their answers, especially regarding missed changes. Given the risks in the safeguards domain associated with missed targets, we would advise that inspectors use digital cameras with caution and take steps to combat their over-confidence, for example, confer with another inspector to confirm their conclusions.

If inspectors are only allowed to make hand-written notes during inspections, our findings show that it is best to take elaborative notes, as the highest d’ performance was observed for participants whose notes recorded aspects of the objects in the array in multiple ways (i.e., visually and verbally). Inspectors using hand-written notes only should be warned that these notes may be less effective at transferring knowledge regarding certain types of changes, like subtle changes about surface material characteristics or object orientation. If these types of changes are critical to note, inspectors may need to put extra care into recording these details to ensure that they are accurately recorded.

4.3 Caveats and Future Work

There were several important differences to note between our experimental paradigm and an actual safeguards inspection that point to the need for future work in this domain.

First, our participant population did not include professional inspectors, who may have their own specialized strategies and domain expertise that could increase the efficacy of their notes. Future work could test whether real inspectors use different strategies or show different patterns of effects across note-taking conditions.

Next, the experimental task was necessarily simpler than real inspection activities, both in terms of the stimuli used and the lack of concurrent inspection tasks. Future work could test the efficacy of note-taking strategies during a simulated facility inspection, to understand how the other tasks performed during inspections (e.g., checking lists of seals, spatial navigation) may interfere or interact with note-taking activities. For example, we might predict that the combined camera and notes condition would provide a bigger benefit when inspectors are moving between different locations in a facility, like they would during real inspections, because it could help offload the memory demands of keeping track of where in the facility the digital photos were taken.

Our participants experienced a shorter time delay between study and test than those experienced by IAEA inspectors, which may have caused higher performance at test than would be expected after a longer delay. To make more practical recommendations for safeguards inspectors, future work should include longer delays between exposure and test to understand if the same principles for effective note-taking hold across delays of weeks or even months.

Finally, participants in our study always used their own complete set of notes and photos at test, whereas in real inspections, the inspector may not be able to take their own digital photos, or their complete set of photos may not be approved for release by the facility’s review and approval process. Moreover, this study cannot address how well the notes could transfer knowledge to a different person who was not exposed to the study environment. As such, future work should test how to best integrate photos taken by someone else (e.g., the facility host) into one’s own notes to maximize their effectiveness for knowledge transfer. Additionally, future work should address which aspects of notes increase their utility as boundary objects to transfer information to a different inspector. The inclusion of these variations could reduce or eliminate the likelihood that effects observed as test were due to enhanced encoding, and thus would provide more pure tests of the ability of the notes alone at transferring knowledge.

References

Gastelum, Z., Matzen, L., Stites, M., Smartt, H.: Cognitive science evaluation of safeguards inspector list comparison activities using human performance testing. In: Proceedings of the 59th Annual Institute of Nuclear Materials Management (INMM) 59th Meeting, Baltimore, MD (2018)

Argote, L., Ingram, P.: Knowledge transfer: a basis for competitive advantage in firms. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 82, 150–169 (2000)

Bosua, R., Venkitachalam, K.: Fostering knowledge transfer and learning in shift work environments. Knowl. Process Manag. 22, 22–33 (2015)

Kerr, M.: A qualitative study of shift handover practice and function from a socio-technical perspective. J. Adv. Nurs. 37, 125–145 (2002)

Lardner, R.: Effective shift handover: a literature review. Offshore Technology Report – Health and Safety Executive OTO (1996)

Patterson, E., Roth, E., Woods, D., Chow, R., Gomes, J.: Handoff strategies in settings with high consequences for failure: lessons for health care operations. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 16(2), 125–132 (2004)

Wilkinson, J., Lardner, R.: Pass it on! Revisiting shift handover after Buncefield. Loss Prev. Bull. 229, 25–32 (2013)

Cook, R., Woods, D., Miller, C.: A tale of two stories: contrasting views of patient safety. National Health Care Safety Council of the National Patient Safety Foundation at the AMA (1998)

Star, S., Griesemer, J.: Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. Soc. Stud. Sci. 19(3), 387–420 (1989)

Trompette, P., Vinck, D.: Revisiting the notion of boundary object. Revue d’Anthropologie des Connaissances 3, 3–25 (2009)

Kiewra, K.: A review of note-taking: the encoding-storage paradigm and beyond. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 1(2), 147–172 (1989)

Kobayashi, K.: What limits the encoding effect of note-taking? A meta-analytic examination. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 30, 242–262 (2005)

Hartley, J.: Notetaking in non-academic settings: a review. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 16, 559–574 (2002)

Mueller, P., Oppenheimer, D.: Technology and note-taking in the classroom, boardroom, hospital room, and courtroom. Trends Neurosci. Educ. 5, 139–145 (2016)

Mueller, P., Oppenheimer, D.: The pen is mightier than the keyboard: advantages of longhand over laptop note taking. Psychol. Sci. 25(6), 1159–1168 (2014)

Paivio, A.: Dual coding theory: retrospect and current status. Can. J. Psychol. 45(3), 255–287 (1991)

Mayer, R., Anderson, R.: The instructive animation: helping students build connections between words and pictures in multimedia learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 84(4), 444–452 (1992)

Craik, F., Lockhart, R.: Levels of processing: a framework for memory research. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 11(6), 671–684 (1972)

Craik, F.: Levels of processing: past, present… and future? Memory 19(5/6), 305–318 (2002)

Wammes, J., Meade, M., Fernandes, M.: The drawing effect: evidence for reliable and robust memory effect in free recall. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 69(9), 1752–1776 (2016)

Holm, S.: A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Stat. 6(2), 65–70 (1979)

R Core Team: R: a language environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria (2017). https://www.R-project.org/

Acknowledgements

Sandia National Laboratories is a multimission laboratory managed and operated by National Technology and Engineering Solutions of Sandia, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Honeywell International Inc., for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under contract DE-NA0003525. SAND2019-1164 C.

The authors would like to thank the IARPA MICrONS Project for generously providing the stimulus images.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Stites, M.C., Matzen, L.E., Smartt, H.A., Gastelum, Z.N. (2019). Effects of Note-Taking Method on Knowledge Transfer in Inspection Tasks. In: Yamamoto, S., Mori, H. (eds) Human Interface and the Management of Information. Visual Information and Knowledge Management. HCII 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 11569. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22660-2_44

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22660-2_44

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-22659-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-22660-2

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)