Abstract

The development of mobile applications has become a means to improve the quality of life of older adults since it is possible to apply to various sectors such as medicine, for example. Also, the population aged 60 or above is growing at a rate of about 3 percent per year. Currently, rapid ageing will occur in different parts of the world as well, so that by 2050 all regions of the world except Africa will have nearly a quarter or more of their populations at ages 60 and above [45]. Likewise, it is known that older people require more time to complete tasks on mobile devices [4] and presents usability problems, so the generic developments of mobile applications do not adapt to their needs and special characteristics. For this reason, this paper addresses which are the main usability challenges that adults face when they interact with de user graphic interface of an application and how they can be made more acceptable to the target population. We summarize the relevant issues in three potential causes: visual, psychomotor and cognitive limitations. In the first category we found problems as the size and sharpness for the visual elements such characters, icons, images, charts and buttons. Also, use hard colors or inappropriate contrast color for the elements represents a significant problem to the seniors. On other hand, we found that the demand for fast and repetitive movements for interaction like moving texts or targets, the maximization in the required number of steps to complete a task and the use of scrollbars represent inconveniences in the second category for the elderly. Finally, in the last category, the most relevant issues are the use of non-significant and irrelevant graphics, or non-meaningful icons with decoration, animation or with no concise text description that goes with it. Besides, use complex texts and navigating through deep, complex and expandable menu hierarchies causes that older persons getting lost within the device menu.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The concept of Human-computer interaction can be defined as one discipline concerned with the design, evaluation, and implementation of interactive computing systems for human use and with the study of major phenomena surrounding them [13]. This field of research is directly related to technological changes and evolves constantly in response to them [26].

With the emergence of mobile innovation, the way people use technology has changed profoundly and an evident example is the massive use of Smartphones, Tablets, IPad’s, mobile devices in general, which have become powerful personal computing devices enabled for interaction through applications that can be used anytime and anywhere thanks to an Internet connection.

Because the use of these mobile technologies have become a trend, several applications are being introduced in these devices in different categories such as entertainment, health, finance, retail, education, social media, etc. [17]. To the first quarter of 2018, Android users were able to choose between 3.8 million apps while Apple’s App Store remained the second-largest app store with 2 million available apps [36].

Among the millions of users who use mobile applications, we can find: children, seniors, persons with disabilities and others. Focusing on seniors, in a study conducted in United States during June 2016, this type of users accessed mobile apps via smartphones for an average of 42.1 h and spent an average of 23.4 h in mobile apps via Tablets in contrast with the youngers who used mobile applications on smartphones 95.3 h and 27.6 h on tablets on average [43]. In general, UIs designers have not had the opportunity to work closely with elderly [16]. Failure to design ‘‘elderly friendly’’ interfaces may lead to reluctance to the use of mobile devices by the elderly [15], while a properly designed UI that respects the elderly’s needs can tackle this issue [15, 25].

Also, a 2014 report on app users revealed that there are actually only a few apps for elderly people [37] that cater for impairments many seniors suffer from (such as less acute vision or reduced tactile sense) or for missing prior knowledge (such as special gestures or typing on a soft keyboard) [6]. For that reason, many elderly people cannot benefit from the large amount of available mobile apps that could support their activities of daily living [6].

The success of any type of application depends on how well it is being used by the user i.e. the usability [17] Due to the above, there is a need to conduct research through one Systematic Review Literature (SLR), following the guidance of Kitchenham [18], which is focused on synthesizing which are the main problems and challenges usability among elderly users when interacting with the UI of a mobile application. Finally, different actions are recommended that should be applied to ensure that this type of user can easily access the different applications and strengthen the growth of the market for which they have been developed.

The paper is structured as follows:

-

Section 2 presents a brief description of the term usability and related concepts.

-

Section 3 specifies the context of usability in mobile applications for elderly people.

-

Section 4 discusses the search method developed in detail to conduct the systematic review.

-

Section 5 reporting the systematic review and presents the results and recommendations on action plans.

-

Section 6 presents some conclusions.

2 Usability

Usability is a core terminology in HCI that can be defined by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (1998) as “the extent to which a product can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use” [14]. The concept of usability is very important to any kind of products because if the users cannot achieve their goals of a way effectively, efficiently and establishing an easy interaction that is reflected in a positive user satisfaction, they can seek another alternative solution to achieve them. In another words, the interaction interfaces should be friendly enough, that allow users to accomplish their purpose in a native or no difficult way [23]. A usable product seeks to achieve three main outcomes: (1) the product is easy for users to become familiar with and competent in using it during the first contact, (2) the product is easy for users to achieve their objective through using it, and (3) the product is easy for users to recall the user interface and how to use it on later visits [26].

According to Shackel (1991) three things are measured about usability of a technology: size, performance and attitude. Dimensional measurements of a technology have direct physical dimensions (width, height, etc.) to measure and are used to determine the volume of products. However, performance measurement is used to determine the time spent and the numbers of mistakes are made during the use of a technology. Attitude scale is used to determine the positive or negative opinions of ones using the technology [30]. In this context, the user interface design of a product is a very important factor that determines the user experience. The UI must be understandable, in a way that users do not make much effort to use it. Also must be attractive to the end user and must contribute to the easy learning, comprehension and operation of its elements. It is important to achieve these aspects to provide a high degree of usability in the applications, to strengthen their use, and guarantee their success. Otherwise, if a software product is difficult to use, hard to understand, or fails to clearly state what it is offering, the user will not use the application anymore [7].

3 Mobile Applications Usability for Elderly People

What is understood as older people or senior citizen? It depends on the context, in Europe an older person is not the same as in Africa, most developed countries set the age of 65 years to define when a person is older [11]. At the moment, the United Nations (UN) agreed cut-off is 60+ years to refer to the older population [44]. This is the age that this study used to consider who is an older person. It is known that as fertility declines and life expectancy rise, the proportion of the population above a certain age rises as well. This phenomenon, known as population ageing, is occurring throughout the world. In 2017, there are an estimated 962 million people aged 60 or over in the world, comprising 13 per cent of the global population. The population aged 60 or above is growing at a rate of about 3 per cent per year. Currently, Europe has the greatest percentage of population aged 60 or over (25 per cent). Rapid ageing will occur in other parts of the world as well, so that by 2050 all regions of the world except Africa will have nearly a quarter or more of their populations at ages 60 and above [45]. Besides, a high percentage of older people in developed countries (Europe, North America, Japan, Australia and New Zealand) owned mobile devices, however they use only mobile phones for very limited purposes, such as for calling or texting in emergencies [11]. But why they do not use other features like mobile apps? Basically, it is because this technology is not adapted to their needs and special features, so it is required facilitate the use of mobile applications for the elderly, so they can adapt quickly, have access to the services that the apps can offer and can get efficient answer to all the actions that they carry out. Regarding the works that study the usability of mobile technology for senior citizen, Villaseca [33] made a review of different studies in this sense. This study shows that older people require more time to complete tasks on mobile devices [4] and it describes problems such as: the size of the screen to read information, the size of menus and interfaces to enter data such as keyboards, functionalities such as de drag and drop, the size of the target (the older tend to make errors when tapping a small target), etc. In the following section, this study presents the strategy to develop the systematic review of the main problems and challenges that elderly people experience when interacting with the user interface of a mobile application.

4 Research Method

In order to gather evidence on the main challenges usability among elderly user when interacting with the user interface of a mobile application, the present study conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) considering the parameters defined in the study of Kitchenham [41] with the aimed at finding all the existing evidence on the factors that impact in usability of mobile applications in the senior citizens. A SLR is defined as a means of identifying, evaluating and interpreting all variables research relevant to a particular research question, or topic area, or phenomenon of interest [41]. Kitchenham establish a set of activities that facilitate the process of a systematic review in the area of software engineering [23]. The steps of this methodology are presented in the following subsections.

4.1 Research Question

The most important activity during the protocol is to formulate the research question, it is also crucial to make this question meaningful and able to identify and/or scope future research activities [41]. The goal of this study was to determine the main barriers usability among elderly users when interacting with the user interface of a mobile application. In this way, the subsequent research question was formulated:

RQ: Which is the main challenge usability among elderly user when interacting with de UI of a mobile application?

This research question has been structured with the help of the PICOC method as suggested by Petticrew and Roberts [40]. Therefore, the comparison criterion was not considered because the objective of this systematic review is not to find the evidence about comparison of different types of usability problems. Table 1, detailed the definition of the general concepts through the use of PIOC.

4.2 Search Strategy

The strategy used for deriving search terms is a reference of the one used in [21] and is specified below:

-

(a)

Derive major search terms from the research questions by identifying Population, Intervention, Outcome and Context. See Table 2.

Table 2. Terms derived from PICOC -

(b)

Find alternative spellings and synonyms for the search terms with the help of a thesaurus. See Table 3.

Table 3. Terms derived from alternative spellings and synonyms -

(c)

Use Boolean OR to construct search strings from the search terms identified in (a) and (b). See Table 4.

Table 4. Construction of terms by using Boolean OR -

(d)

Use Boolean AND to concatenate the search terms and restrict the research.

The resulting search string allows identifying as many academic papers as possible, which describe the main usability problems of the elderly when interacting with the user interface of mobile software. See Table 5.

4.3 Search Process and Resources

The search process was executed on October 15, 2018 and it was directed towards using search engines and recognized online databases to search for primary and secondary studies. No additional studies were considered. In order to avoid omitting any evidence, the search process will include literature published since 2013 to date. 2013 was chosen as the starting limit because a search test was conducted, and the most relevant results were found in that year. Grey literature was also excluded.

The following electronic resources were chosen because they were used by some examples of systematic reviews from discipline of software engineering [21] and they were suggested by the digital library of the University. All databases were searched using appropriate keywords and headings related to the concepts usability, mobile applications, elderly people and user interface.

Online Database:

-

IEEE XPLORE

-

SCOPUS

-

ProQuest Computing

-

ACM Digital Library

4.4 Selection of Studies

Once the articles that met the search string were obtained, an analysis of the title, authors, abstract and keywords of each study was carried out to determine their relevance. Also, a study selection criterion was developed. This study is intended to identify those studies that provide direct evidence about the research question [41]. Inclusion and exclusion criteria should be based on the research question and they should be piloted to ensure that can be reliably interpreted and that they classify studies correctly [41] Papers that satisfy at least one of the following conditions, published between Jan 1st 2013 and September 30th 2018, were included in this analysis:

-

Tittle, keyword list, and abstract make explicit that the paper is related to usability problems when the elderly interacting with de user interface of a mobile application.

-

The study reports on the analysis of the interface of the any type (domains) of mobile application: health, education, social media, etc.

-

The study presents usability problems among senior when interacting with the user interface of any mobile device: smartphone, iPad’s, tablets, mobile touch screen devices in general, etc.

-

The paper presents recommendations and guidelines to design an appropriate graphical user interface focus on the elderly.

-

The paper focuses its analysis of usability of mobile devices only elderly people.

-

The study focuses their analysis on specific communities of the world.

-

The paper presents comparisons between different age groups (younger, older, middle age) with regard to usability problems in mobile applications.

The studies that met at least one of the following aspects will be excluded from this systematic review:

-

Duplicate reports of the same study (the most complete version of the paper was included in the research).

-

Informal literature.

-

The study is not written in English.

-

The year of publication of the study was before to 1st January 2013.

-

The publication is not accessible.

-

The study has not developed its analysis regarding the use of touch-based mobile devices (for example, tablets, smartphones, iPads) by seniors.

-

The paper describes the use of a specific platform or presents how to develop and design a specific application without mainly addressing the problems that the elderly face when interacting with the GUI of the application.

-

The study presents the intention of use or the behavior of an older person on a specific mobile application without focusing mainly on the usability of the elements of the graphic interface of the application.

-

The study presents an analysis of usability of applications in the following areas: augmented reality, internet of things, web platforms and mobile robots.

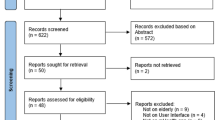

The Table 6 summarize the results obtained for each four databases after conducting the search process and selecting them. As a result, we obtained 201 studies of which 24 papers were classified as duplicates. Finally, 177 unique studies were obtained and after the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 28 papers were selected and included in the systematic review.

4.5 Data Extraction Strategy

The objective of this section is to design data extraction form to accurately record the information researchers need from the studies [41]. For this reason, the strategy to be adopted for recording the data is given below:

-

Data Extraction Form

The design of the data extraction form was performed according to the protocol proposed by Kitchenham [41] and has been designed to collect all the information needed to address the research question, also it form provides standard data. For each resulting paper of our search, we developed the following structure given in Table 7.

Table 7. Data extraction form

5 Systematic Review Results

According to the studies reviewed, it can be concluded that the usability problems that older people finding when interacting with the graphic interface of a mobile application have their causes in three broad categories: Visual limitations, psychomotor limitations and cognitive limitations. On the following lines will detail which are the problems that constitute each of these groups.

5.1 Visual Limitations

Vision is the most important way how technology can present information to the user. As the limitations of a human eye depend on age, seniors have mostly worse vision [31]. Therefore, the old eye has a slower accommodation between dark and light places. It cannot quickly change the focus, or react to fast-changing brightness [31]. For these reasons, the difficulties that older users have when using a mobile application are:

-

Find small and unclear visual elements such characters, icons, images or graphical content, charts, font size on charts and buttons on the screen [2, 3, 10,11,12, 20, 22, 25, 27, 29, 34, 35, 38]. Also, display text that uses a very small or thin font represents an issue to the elderly [31].

-

Find touch targets that are not big enough [5].

-

Visualizing and using a keyboard too small [12].

-

The size of on-screen buttons has a clear influence on interaction speed and accuracy [22].

-

Find inappropriate or hard colors for the icons, images or graphical content, for example those that are too bright [2, 29].

-

Visualize an inappropriate contrast color [10, 32], for example a very strong color during the user interaction [11, 12, 24]. Find color combinations with a low contrast [31].

-

Don’t find a color coding to differentiate and group the elements [38].

-

Visualize characters on the keypad that are not clearly visible; especially in the dark and night time [20].

-

Don’t find a wider space between lines and letter [10] on the GUI. Also it was detected that the performance of elderly was significantly influenced by spacing and location of the target [35].

-

Do not understanding and distinguishing the buttons from one another either visually or by touch [24].

-

Not visualize sufficiently large gaps between individual elements, particularly between elements such as buttons that are touch targets [5, 20].

-

Visualize very small menus sizes and interfaces to enter data such as keyboards (virtual and physical). Also, find that the size of the target it is too small (the older tend to make errors when tapping a small target) represents a problem for the elderly [11].

Recommendations

-

In general, older adults found enlarging the text size to be helpful [25].

-

Options to zoom in and increase the font size [24].

-

Allow to adjust font size and contrasting colors [9].

Likewise, the following recommendations are specified in the Android application development guide:

-

By providing increased contrast ratio between the foreground and background colors in the app, it will be easier for users to navigate within and between screens. For large text, 18 points or higher for regular text and 14 points or higher for bold text, you should use a contrast ratio of at least 3.0 to 1. For small text, smaller than 18 points for regular text and smaller than 14 points for bold text, you should use a contrast ratio of at least 4.5 to 1 [39].

-

Uses cues other than color to distinguish UI elements within the screens of the app. These techniques could include using different shapes or sizes, providing text or visual patterns, or adding audio [39].

-

Color can help communicate mood, tone, and critical information. Use color so that all users can understand the content is fundamental to accessible design. Choose primary, secondary, and accent colors for the app that support usability [39].

-

Clear and helpful accessibility text is one of the primary ways to make UIs more accessible. Accessibility text refers to text that is used by screen reader accessibility software, such as TalkBack on Android, VoiceOver on iOS, and JAWS on desktop. Screen readers read all text and elements (such as buttons) on screen aloud, including both visible and nonvisible alternative text [39].

On the other hand, the following recommendations are specified in the iOS application development guide:

-

Provide the feature of zoom to magnifies the entire device screen [42].

-

Voice Control, that allows users to make phone calls and control iPod playback using voice commands [42].

5.2 Psychomotor Limitations

The general rule is that seniors require about 50–100% more time for completion of a task than adults fewer than 30. Many interfaces require very fine movements. The consequences of an error are frustrating. For example, if a user accidentally removes the file, or s/he is an inaccurate during the drag and drop of the file, so s/he needs to start over and over again [31]. The principal issues that the elderly can find in the interface user of an application mobile are the following.

-

Interacting with moving text and targets, when the interface item unexpectedly moves, makes it difficult for the user to interact. Also the elderly has problems with text entry using virtual keyboards [10, 12, 24].

-

Demanding fast and repetitive movements for interaction, maximization the required number of steps to complete a task. In other words, the user has difficulty in performing a sequence of actions/navigations [10, 12, 28].

-

The use of scrollbars is maximized or do not placed on the side of the phone [24].

-

Have to do functions that require user to perform unfamiliar and challenging actions for example, “drag and drop” [11, 29].

-

Can’t identify tappable areas on touchscreens [24].

-

Have difficulty in assessing the function of buttons or can have difficulty understanding mobile scroll bars [22].

-

Detecting which buttons or target to press, which often leads to long taps of a virtual button or pressing the wrong button on the virtual keyboard. This can be caused by the buttons being very close to each other (to the target button) [1, 35].

-

Do not find colorful and not animated icons, which are supported textually. However, it is known that labels are more efficient for older people to initially use icon [1].

-

Must do actions of scrolling and tapping are confusing. In addition, pop-up windows for request messages could be stressful for the user [27].

Recommendations

-

Reduced number of interactions [38].

-

Use a simple menu structure and only essential functionality [34].

-

Instead of using interaction concepts such as scrolling and drag and drop, previous research proves that the elderly only likely to use traditional pressing button method [2].

Likewise, the following recommendations are specified in the Android application development guide:

-

By providing larger touch targets, it will be substantially easier for users to navigate the app. In you want the touchable area of focusable items to be a minimum of 48dp × 48dp [39].

5.3 Cognitive Limitations

Memory ability declines with age. It has been generally accepted that the capacity of working memory significantly decreases with age. Regarding long-term memory, however, the decline is not global. Whereas semantic memory is trivial, age-related loss is episodic, and procedural memory is common. In addition, deficits in prospective memory, that is, the ability to remember to carry out an intended action, are prevalent among older people [10]. When the interface presents the information in inappropriate way, many people get confused and tend to blame themselves rather than the application. The effective interface is the one that helps users in completing their goals with a little confusion and less errors as possible [31]. The main difficulties that the older users experiment are:

-

Use complex texts and navigating through deep and complex menu hierarchies, use moving and expandable menus, which causes that the elderly getting lost within the device menu. Not using standardized menus or one-level navigation causes the user to have difficulty understanding the menu hierarchy [8,9,10, 12, 35].

-

Use of non-significant and irrelevant graphics, many ambiguous pictograms and non-meaningful icons with decoration, animation or with no concise text description that goes with it. All of this causes confusion about the meanings of the interface icons and makes it difficult to know and recognize what each one represents. In addition to that, using similar icons for labeling UI elements playing distinct roles represent a difficulty for the elderly [1, 8,9,10, 19, 24, 29, 31].

-

Use ambiguous uncommon terms (abbreviation meaning), employs terms and expressions that are difficult to understand (inadequate labels), the language used is vague and not meaningful and use over-complicated jargon or use metaphors that look familiar to the elderly but are not [5, 12, 28, 29, 34].

-

Do not apply a standard (well-known) icon design configuration, which is consistent in size and shape [28].

-

The use of drop down menus is proven to be an issue because precise movements are physically challenging for this population group [38].

-

Can´t find the option of refining the search by applying further criteria. When displaying the search results, the availability of sorting options (e.g. according to date, location, and other criteria) is no available [5].

-

Find unclear instructions on how to proceed to use a certain function. Lack of instruction, not intuitive instructions, lack of directions and lack of help [27, 35].

-

Use long content that requires memory recall affects older adults with cognitive impairments [38].

Recommendations

-

Use menu structure must be simple and flattened (menus standardized and customized [11]).

-

Use easy-to-use menus should be preferred.

-

Information about the current menu item helps users to navigate [5].

-

If icons are used for navigational purposes, these should be easily identifiable in terms of their function [5].

-

Older adults preferred to use colorful, not animated icons, which are supported textually. Also, their study found that labels are more efficient for older people to initially use icons [1].

-

Animation should be avoided because it would interfere with the focus of senior citizens to interact with the computer. Icon design should be simple to understand and refers precisely to the function of the icon [2].

-

With regard to the search process, good positioning of the search fields is just as important as transparency [5].

Likewise, the following recommendations are specified in the Android application development guide:

-

It is important to provide useful and descriptive labels that explain the meaning and purpose of each interactive element to users [39].

-

Developers should arrange related content into groups so that accessibility services announce the content in a way that reflects its natural grouping [39].

-

Make sure users can navigate through your app’s layouts using keyboards or navigation gestures, avoid having UI elements fade out or disappear after a certain amount of time [39].

On the other hand, the following recommendations are specified in the iOS application development guide:

-

Provide a label that very briefly describes the element and begins with a capitalized word [42].

-

An accessible user interface element must provide accurate and helpful information about its screen position, name, behavior, value, and type [42].

-

Provide the current value of an element, when the value is not represented by the label. For example, the label for a slider might be “Speed,” but its current value might be “50%.” [42].

6 Conclusions

The main goal of this paper is to know which are the main usability issues faced by the elderly when interacting with the graphic interface of a mobile application. The recognized problems can be part of three large categories: visual limitations, psychomotor limitations and cognitive limitations. These groups represent the causes of the difficulties that older persons find when using the apps.

According to the primary studies reviewed, the usability issue that was identified a greater number of time in the first category was finding small and unclear visual elements such characters, icons, images or graphical content, charts, font size on charts and buttons on the app. Likewise, we found that the demand for fast and repetitive movements for interaction like moving texts or the maximization in the required number of steps to complete a task represents significant problems in the second category for the seniors. Finally, in the last category we found that the main issue was the use of non-significant and irrelevant graphics, many ambiguous pictograms and non-meaningful icons with decoration, animation or with no concise text description that goes with it. All of this causes confusion about the meanings of the interface icons and makes it difficult to know and recognize what each one represents.

Besides, use complex texts and navigating through deep, complex and expandable menu hierarchies causes that the elderly getting lost within the device menu.

Finally, considering the analysis of the Android and IOs guides to develop more accessible applications, it is concluded that although there are several recommendations in each of the three defined limitations: visual, psychomotor and cognitive, many of the applications that are currently sold in the market lack special features for this group of users. For example, it is a fact that color can help communicate mood, tone, and critical information so it is recommended to use color so that all users can understand the content is fundamental to accessible design. Likewise, choosing primary, secondary and accent colors is important for the application to support usability. So, this kind of recommendations should be considered primarily by developers when creating a new application.

References

Al-Razgan, M., Al-Khalifa, H.S.: SAHL: A touchscreen mobile launcher for Arab elderly. J. Mob. Multimed. 13(1–2), 75–99 (2017)

Azir Rezha, N., et al.: Tackling design issues on elderly smartphone interface design using activity centered design approach. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 9(8), 1190–1196 (2014)

Azuddin, M., et al.: Older people and their use of mobile devices: issues, purpose and context. In: The 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology for the Muslim World (ICT4M), pp. 1–6 (2014)

Lin, C.J., Hsieh, T.-L., Shiang, W.-J.: Exploring the interface design of mobile phone for the elderly. In: Kurosu, M. (ed.) HCD 2009. LNCS, vol. 5619, pp. 476–481. Springer, Heidelberg (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-02806-9_55

Darvishy, A., Hutter, H.-P.: Recommendations for age-appropriate mobile application design. In: Di Bucchianico, G., Kercher, Pete F. (eds.) AHFE 2017. AISC, vol. 587, pp. 241–253. Springer, Cham (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60597-5_22

Diewald, S., et al.: Mobile AgeCI: potential challenges in the development and evaluation of mobile applications for elderly people. In: Moreno-Díaz, R., Pichler, F., Quesada-Arencibia, A. (eds.) EUROCAST 2015. LNCS, vol. 9520, pp. 723–730. Springer, Cham (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27340-2_89

Engel, E., Öncü, S.: Conducting preliminary steps to usability testing: investigating the website of Uluda University

Fletcher, J., Jensen, R.: Mobile health: barriers to mobile phone use in the aging population. On-Line J. Nurs. Inform. OJNI 19(3) (2015)

Fletcher, J., Jensen, R.: Overcoming barriers to mobile health technology use in the aging population. On-Line J. Nurs. Inform. OJNI 19(3) (2015)

Gao, Q., et al.: Design of a mobile social community platform for older Chinese people in urban areas. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 25(1), 66–89 (2015)

García-Peñalvo, F.J., Conde, M.Á., Matellán-Olivera, V.: Mobile apps for older users – the development of a mobile apps repository for older people. In: Zaphiris, P., Ioannou, A. (eds.) LCT 2014. LNCS, vol. 8524, pp. 117–126. Springer, Cham (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07485-6_12

Gonçalves, V.P., et al.: Providing adaptive smartphone interfaces targeted at elderly people: an approach that takes into account diversity among the elderly. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 16(1), 129–149 (2017)

Hewett, T.T., et al.: ACM SIGCHI Curricula for Human-Computer Interaction. ACM, New York (1992)

International Organization Standardization (ISO): Ergonomic requirements for office work with visual display terminals (VDTs)—part 11: Guidance on usability

Balata, J., et al.: KoalaPhone: touchscreen mobile phone UI for active seniors. J. Multimodal User Interface 9, 263–273 (2015)

Johnson, J., Finn, K.: Designing User Interfaces for an Aging Population: Towards Universal Design. Morgan Kaufmann, USA (2017)

Kalimullah, K., Sushmitha, D.: Influence of design elements in mobile applications on user experience of elderly people. Presented at the Procedia Computer Science (2017)

Kitchenham, B.: Procedures for Performing Systematic Reviews. Software Engineering Group Department of Computer Science Keele University and Empirical Software Engineering National ICT Australia Ltd., United Kingdom, vol. 33, pp. 1–26 (2004)

Lai, L.-L., Lai, C.-R.: Designing interface for elderly adults: access from the smartphone to the world. In: Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), vol. 9469, pp. 306–307 (2015)

Malik, S.A., Azuddin, M.: Qualitative findings on the use of mobile phones by Malaysian older people. In: International Conference on Advanced Computer Science Applications and Technologies, pp. 435–439 (2013)

Riaz, M. et al.: A Systematic Review of Software Maintainability Prediction and Metrics. In: Proceedings of the 2009 3rd International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement, pp. 367–377. IEEE Computer Society, Washington, DC (2009). https://doi.org/10.1109/ESEM.2009.5314233

Nicol, E., et al.: Re-imagining commonly used mobile interfaces for older adults. Presented at the MobileHCI 2014—Proceedings of the 16th ACM International Conference on Human–Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services (2014)

Paz, F., Pow-Sang, J.A.: Current trends in usability evaluation methods: a systematic review. In: 7th International Conference on Advanced Software Engineering and Its Applications, pp. 11–15 (2014)

Petrovcic, A., et al.: Design of mobile phones for older adults: an empirical analysis of design guidelines and checklists for feature phones and smartphones. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 34(3), 251–264 (2018)

Piper, A.M., et al.: Understanding the challenges and opportunities of smart mobile devices among the oldest old. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 8, 83–98 (2016)

Punchoojit, L. et al.: Usability studies on mobile user interface design patterns: a systematic literature review. In: Advances in Human-Computer Interaction, New York (2017)

Ruzic, L., Sanford, J.A.: Usability of mobile consumer applications for individuals aging with multiple sclerosis. In: Antona, M., Stephanidis, C. (eds.) UAHCI 2017. LNCS, vol. 10277, pp. 258–276. Springer, Cham (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58706-6_21

Salman, H.M., et al.: Heuristic evaluation of the smartphone applications in supporting elderly. In: Saeed, F., Gazem, N., Mohammed, F., Busalim, A. (eds.) IRICT 2018. AISC, vol. 843, pp. 781–790. Springer, Cham (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99007-1_72

Salman, H.M., et al.: Usability evaluation of the smartphone user interface in supporting elderly users from experts’ perspective. IEEE Access 6, 22578–22591 (2018)

Shackel, B., Richardson, S.J.: Human Factors for Informatics Usability. Cambridge University Press, New York (1991)

Slavicek, T., et al.: Designing mobile phone interface for active seniors: user study in Czech Republic. In: 5th IEEE Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), pp. 109–114 (2014)

Sookhanaphibarn, K., et al.: Optimum button size and reading character size on mobile user interface for Thai elderly people. In: IEEE 6th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics (GCCE), pp. 1–2 (2017)

Urdaibay-Villaseca, P.T.: Usability of Mobile Devices for Elderly People. National University of Ireland, Galway (2010)

Van Biljon, J., Renaud, K.: Validating mobile phone design guidelines: focusing on the elderly in a developing country. Presented at the ACM International Conference Proceeding Series (2016)

Wong, C.Y., Ibrahim, R., Hamid, T.A., Mansor, E.I.: Usability and design issues of smartphone user interface and mobile apps for older adults. In: Abdullah, N., Wan Adnan, W.A., Foth, M. (eds.) i-USEr 2018. CCIS, vol. 886, pp. 93–104. Springer, Singapore (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1628-9_9

App stores: number of apps in leading app stores 2018|Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/276623/number-of-apps-available-in-leading-app-stores/

deloitte-au-tmt-smartphone-generation-gap-011014.pdf. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/au/Documents/technology-media-telecommunications/deloitte-au-tmt-smartphone-generation-gap-011014.pdf

Integrating Universal Design (UD) Principles and Mobile Design Guidelines to Improve Design of Mobile Health Applications for Older Adults - IEEE Conference Publication. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7052509

Make apps more accessible|Android Developers. https://developer.android.com/guide/topics/ui/accessibility/apps

Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Systematic+Reviews+in+the+Social+Sciences%3A+A+Practical+Guide-p-9781405121101

systematicreviewsguide.pdf. https://www.elsevier.com/__data/promis_misc/525444systematicreviewsguide.pdf

Understanding Accessibility on iOS. https://developer.apple.com/library/archive/documentation/UserExperience/Conceptual/iPhoneAccessibility/Accessibility_on_iPhone/Accessibility_on_iPhone.html#//apple_ref/doc/uid/TP40008785-CH100-SW1

U.S. mobile app hours by device and age 2016|Statistic. https://www.statista.com/statistics/323522/us-user-mobile-app-engagement-age/

WHO|Proposed working definition of an older person in Africa for the MDS Project. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/en/

World Population Prospects. https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/publications/files/wpp2017_keyfindings.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Elguera Paez, L., Zapata Del Río, C. (2019). Elderly Users and Their Main Challenges Usability with Mobile Applications: A Systematic Review. In: Marcus, A., Wang, W. (eds) Design, User Experience, and Usability. Design Philosophy and Theory. HCII 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 11583. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23570-3_31

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23570-3_31

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-23569-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-23570-3

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)