Abstract

The development of Active Assisted Living (AAL) technologies requires a clear understanding of the distinct needs and challenges faced by senior citizens. Yet, these relevant insights are often missing, which makes the application of User-Centered Design (UCD) approaches an even more important factor significantly influencing the success of these envisioned solutions. The goal of the work presented in this paper was therefore to identify UCD approaches commonly used with AAL projects, and to evaluate their compatibility with the elderly target group. A mixed-methods approach composed of an online survey targeted at European AAL Projects, and a guided interview study with experts, revealed that AAL projects often apply techniques which are popular and well-known in the design and development community, but not specific to UCD. Furthermore, we found that many UCD techniques are unknown, even to experts, or simply too complicated to be used with elderly users.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Throughout the second half of the 20\(^\mathrm{th}\) century, we have been seeing a continuous demographic shift, pointing to a significant reduction of citizens aged 64 and younger (i.e., people of working age) and a noticeable increase of those aged above (for Europe cf. [7]). With this consequent ageing of the population, the burden on national health and social care systems is increasingly rising, for older adults have a stronger demand for health and social services than younger people [12]. Solutions based on modern Information and Communication Technology (ICT) have shown to contribute to a better healthcare provision and thus help relieve some of this financial pressure resting on public providers. Active Assisted Living (AAL) technologies, which fall under the above-mentioned ICT solutions, are emerging and have been receiving public funding and support for several years. Yet, while research in the field of ICT for elderly is thriving and backed by political support and funding programs, the widespread adoption and respective market success of such products is still to be seen [13, 26]. To this end, it has been shown that User-Centered Design (UCD) approaches support the design and development of technologies, fostering usability and furthermore increasing user acceptance. However, these approaches are not generally applicable and may need alteration when utilized during the design and development of AAL solutions. The work presented in this paper thus aimed at a better understanding of the type of UCD methods that are currently employed when working with elderly user groups. To this end, our analysis was guided by the following research question:

To what extend and how expedient are User-Centered Design approaches applied in the development of elderly focused Active Assisted Living technologies?

2 Related Work

There is a prevailing viewpoint within the field of AAL that UCD approaches are essential for achieving a high level of product usability, product safety and product acceptance. The importance of this subject has also been taken up by the AAL Joined Programme (JP) which made the inclusion of UCD approaches a general requirement to be applied in projectsFootnote 1. So far, there has been only little research on whether this shift towards implementing UCD in AAL actually took place. For projects participating in the first phase of the AAL JP (i.e., between 2008 and 2013) previous analyses have shown an uptake of user representation in the design and development processes, but a lack of sufficient user integration and user contribution [5]. A systematic literature review on the status quo by Queirós and colleagues [23] detected only a small number of articles concerning the involvement of end users into the development, evaluation and validation phases of AAL projects. Adding to this, Calvaresi et al. [2] conducted a systematic literature review on papers in the domain of AAL focusing particularly on Germany. Also they did not find any evidence as to whether existing AAL developments meet the actual end user needs and thus proposed an increase in efforts put into understanding these needs and preferences. A study conducted with AAL projects in Austria did point to some success in integrating users, yet it also showed that projects utilized methods which did not specifically relate to UCD [14]. Consequently, the use and dissemination of more advanced UCD approaches was endorsed. Finally, conducting a qualitative study including participants with extensive experience in AAL, Hallewell-Haslwanter and Fitzpatrick further revealed a general lack of knowledge regarding the correct application of UCD methods in AAL, and the non-existence of UCD techniques specifically geared towards engaging elderly users [11].

3 Methodology

Based on this previous work and driven by the earlier outlined research question, our goal was to explore UCD methods in AAL projects, and investigate their involvement of elderly and/or old-adult participants in the development process. As elderly we considered people between 60 and 75 years of age, as old-adults those aged above 75 [1, 9, 17, 20]. Doing this, we followed a mixed-methods approach. First, an online survey gave insights into the use of UCD methods in currently ongoing as well as already completed AAL projects participating in the AAL JP. It furthermore asked participants to rate the suitability and perceived efficiency of different UCD techniques in light of their specific projects. A subsequently conducted interview study asked open-ended questions to experts so as to obtain a more in-depth understanding of the appropriateness of UCD methods when used with elderly participants, and the respective challenges which need to be tackled in such contexts.

3.1 Online Survey

The online survey was available for the duration of 6 weeks during April and May 2019 and targeted directly at members of AAL JP projects who had sufficient information on the therein applied procedures. Questions were organized in three sections. The first section, asked participants to provide relevant information on the year and duration of their AAL project, its test regions/countries, and the area the respective AAL product was situated in.

In the second section, participants were confronted with five categories of UCD methods, which held a total of 46 different UCD techniques found in the literature (cf. Tables 1 and 2). This list was created in a multi-stage process in which we used the listings of Still and Crane [29], Maguire [19], Shneiderman et al. [24], Glende [10], Dwivedi et al. [6], Spinsante et al. [27], and Czaja et al. [3] to select techniques and respective categories, aiming to include all common UCD techniques without being too excessive. For each category, participants were then asked to select those UCD techniques that were utilized in their AAL project. At the end of each category, the respondents were furthermore asked to state, if they were familiar with the techniques they did not select. Next they were asked to state for each technique they did apply in their project, the phase of the product development in which this application happened. In a next step, participants were then asked to evaluate these specific UCD techniques according to their preparatory effort (e.g., procurement of working materials, training of moderators, selection of representative test participants), their financial effort (i.e., level of financial effort/resources required for the use of the specific UCD technique), their conduction effort (i.e., the need for technical equipment, premises, moderators or assistants), their evaluation effort (i.e., the perceived effort attached to the evaluation of the results produced by the selected UCD technique), their feasibility in terms of validity (i.e., the degree to which the technique did measure what it claimed to measure), their scalability (i.e., the perceived effort required to include more participants), their ‘fun factor’, and to what degree participants would recommend them. All parameters were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (Low: 1.0–1.4; Moderately Low: 1.5–2.4; Moderate: 2.5–3.4; Moderately High: 3.5–4.4; High: 4.5–5.0)

Finally, in the third section, participants were asked to describe the developed solution in some more detail and to rate the level of success they think their solution has attained.

3.2 Interview Study

For the follow-up interview study we directly contacted UCD/AAL experts through phone or Skype calls. Targeted participants had to have either extensive practical experience in conducting UCD within AAL projects, or had to be dedicated experts in specific UCD techniques. To this end, potential interview partners were considered as qualified either based on their academic credentials or based on recommendations. Those who agreed to participate came from research institutions in either Austria or Germany, had extensive experience with research and development in the field of AAL and are still active in the AAL, HCI and/or UCD area. The guiding questions we asked participants during these interviews aimed at elaborating on the suitability of different UCD techniques when used in AAL projects.

4 Results

A total of 27 European AAL projects responded to our survey request and completed the entire survey. More than 80% of the projects were conducted in the past five years. With this data set we particularly looked at the frequency of application and the level of familiarity the different UCD techniques held. With respect to the follow-up interview study, we were able to conduct 5 guided interviews (EP1–EP5), all of which lasted between 40 and 60 min. In order to analyze the data, we used a content analysis method based on a combination of deductively and inductively generated codes. We followed the coding method proposed by Lazar and colleagues [16], where the responses to the open-ended questions were assigned to types of UCD methods (i.e., deductive codes) and additional concepts evolving from the data (i.e., inductive codes). We employed magnitude coding so as to evaluate the frequency of feedback and consequently its relevance and informative value [16].

4.1 Creativity Methods

With respect to creativity methods, our results show that brainstorming is the most often applied technique (70%), while all other techniques are hardly considered, even though techniques like crowd-sourcing (44%), Six Thinking Hats (41%) and the Walt-Disney-Method (41%) were familiar to over 40% of the participants (cf. Fig. 1).

Focusing on the brainstorming technique, Table 3 illustrates that the preparatory effort (mean 2.47) and the financial effort (mean 1.95) were assessed as moderately low, while the conduction effort (mean 2.72) as well as the evaluation effort (mean 3.42) were both rated as moderate. The feasibility received a moderately high mean of 3.63 and the scalability was rated as moderate (mean 3.00). Further on, participants considered the fun factor as moderately high (mean 3.53) and likewise the recommendation of brainstorming received a moderately high score (mean 3.89).

To expand upon these results, the open-ended questions posed to experts revealed that brainstorming is often not applied as UCD method with elderly participants, but rather with project members or external professionals (EP1, EP4 and EP5). To this end, EP5 argues that brainstorming is not suitable for older adults, as they could be confused or over-strained by the unstructured characteristic of the technique. In contrast, EP2 remarked that in their project brainstorming was not applied as a standalone technique but as part of other more comprehensive UCD methods. Overall, only 5 of the 16 listed creativity methods received a partial positive assessment by the experts. EP3, for example, deems the 6-3-5 brainwriting and the gallery braindrawing technique as very applicable for the target group, while EP4 experienced good results with utilizing the Osborn-checklist as well as the idea contest, as long as it is adapted to the specifics of the elderly participants. Finally, EP2 emphasized the identification method as suitable, since it helps developers gain a deep understanding of the user group. However, the fact that all of these methods were also often rated as too complex or inappropriate for the elderly user group, points to a great level of disagreement among experts. Other techniques were either not known or not at all addressed as being used.

4.2 Analysis Methods

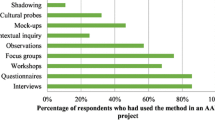

As for analysis methods, interviews (96%), focus group discussions (89%), written surveys (70%) and observations (67%) achieved notable high application and familiarity ratings. In contrast, the NAUA method and the Kano Model were not applied at all and barely known. The contextual inquiry technique revealed a discrepancy as it was familiar to over half of all participants (56%) but applied by only 26% (cf. Fig. 2).

Table 4 shows that interviews received a moderately high score for the preparatory effort (mean 3.62), the conduction effort (mean 3.96) and the evaluation effort (mean 4.31), while the financial effort (mean 2.73) was perceived as moderate. Focus groups received similar ratings for these parameters (cf. Table 5). In terms of feasibility, both techniques were rated as moderately high, with interviews (mean 4.04) receiving a higher score as focus group discussions (3.63). The scores for scalability, fun factor and the degree of recommendation for both methods were also similar. Here, the focus group discussions received a higher rating with respect to the fun factor (mean 3.46) whereas interviews seem to be more recommended (mean 3.96).

In Table 6 it can be seen that preparatory effort for written surveys was perceived similar to interviews (mean 3.63 vs. mean 3.62). In contrast, observations received a lower score with a mean of 2.89 (cf. Table 7). Moreover, written surveys and observations showed similarities in terms of a moderate financial effort, a moderate conduction effort and a moderately high level of feasibility. The evaluation effort for the written survey was rated as moderate (mean 3.42) and for the observation as moderately high (mean 3.78), although both scores are rather close. A greater variation can be observed for scalability, which was rated as moderately high for the written survey (mean 4.05) and as moderate for the observation (2.78). Both methods received a moderately high level of recommendation, whereas the score for observations shows an upwards tendency (mean 4.06).

From the experts’ point of view, EP1 and EP2 emphasized the suitability of using interviews with older adults. The involving nature of interviews makes older adults feel valued and leads to more comprehensive answers. With respect to focus groups, four of the five experts stated that they had successfully used this method with elderly participants and that it had provided valuable and extensive insights, although the preparatory and evaluation efforts were considered high. EP1 and EP5 further highlighted the enjoyment older adults felt when interacting with other participants, while EP3 noted that, due to the group dynamics which may evolve, the method could over-strain participants. As for the written surveys, replies were rather controversial. That is, EP1 reported that often relatives or professional caregivers completed the surveys and EP3 added that elderly participants were often overwhelmed with the technical complexity of AAL questionnaires. In contrast, EP 2 and EP 4 reported that written surveys were deemed a successful method and well applicable with elderly participants. Also the contextual inquiry method was identified as suitable and expedient in the context of AAL technology development (4 out of 5 experts). EP2, for example, emphasized the importance of this technique for receiving usability insights, and EP5 accentuated that this method may be particularly useful in cases where the product developers are not that familiar with the actual area of application. Finally, observations were considered an integral part of the contextual inquiry and as useful to gain insights on a specific problem.

4.3 Evaluation Methods

Investigating different evaluation methods, Fig. 3 shows that only the System-Usability-Scale (44%) and the Benefit Analysis (33%) were applied by more than one third of the participating projects, although Quantitative UX (User Experience) Surveys (33%) as well as Simple Point Scoring (30%) and the ISO 9241 Questionnaire (30%) were known by at least 8 of the respondents.

Table 8 and Table 9 illustrate that the overall perceived efforts for the System-Usability-Scale (SUS) were lower than for the Benefit Analysis. Notable differences can also be found for the preparatory effort, which was rated as moderately low for the SUS (mean 1.92), and as moderate for the Benefit Analysis (mean 3.33). Moreover, for the evaluation effort the moderately low mean score for the SUS and the moderately high mean score for the Benefit Analysis differed by over 1.5 points. In turn, the Benefit Analysis was rated as more feasible (mean 4.11) and received a higher degree of recommendation (mean 4.11). The fun factor was perceived as moderately low for the SUS and as moderate for the Benefit Analysis. Both methods received a similar, moderately high, score for their scalability.

The interviews with the experts revealed similar results as the online survey. From the eight listed techniques, four were either not applied or not addressed. Thereby, EP4 considered the ISO 9241 Questionnaire as too general and therefore as inappr opriate to be used in the context of AAL, yet he/she stated that the Benefit Analysis and the Simple Point Scoring were successfully applied in previous AAL development projects (note: none of the other experts addressed or applied these methods). The most extensive feedback was received for the Systems-Usability-Scale and the Quantitative UX Surveys. While EP1 stated that the SUS had been used successfully with elderly participants and provided valuable results, EP4 and EP5 questioned its suitability. EP4 particularly criticized the general manner of the questions and the low informative value of the outcome, while EP5 deemed the SUS as too complex to be used with older adults. As for the Quantitative UX Survey, EP2 reported good applicability and emphasized the capability of the tool as a means to assess the emotional level of participants. EP5, on the other hand, deemed the method as too complicated for the elderly user group, while the other experts did not consider this method at all. Finally, EP3 noted that standardized questionnaires or worksheets cannot capture the complexity and different parameters which are often present in AAL projects.

4.4 Test Methods

With respect to test methods, Field Tests (74%) and User Experience (UX) Tests (59%) were the most often applied techniques in this category and also received the highest familiarity ratings (cf. Fig. 4). Notable in this section is that the Card Sorting technique was known to 17 participants but only applied by one.

Tables 10 and 11 illustrate that the preparatory effort, the conduction effort and the evaluation effort were rated as moderately high for both the Field Test and the UX test. A clear difference between both techniques can be found, however, in the financial effort, which was perceived as moderately high for the Field Test (mean 4.10) and as moderate for the UX Test (mean 2.94). The feasibility, the fun factor and the degree of recommendation for the Field Test and the UX Test were all rated as moderately high, whereas the scalability for the UX test was rated with a moderate score compared to the moderately high score for the Field Test. To this end, it should further be noted that the Field Test shows a mode of 5 for the parameters preparatory effort, financial effort, conduction effort, feasibility and degree of recommendation.

From an experts’ point of view, Field Test were assigned a good level of applicability in AAL projects. EP2 and EP3, in particular, considered the method as essential for developing AAL technologies according to the needs and preferences of the target group. EP1 further added that Field Tests would provide valuable suggestions for improving the functionalities of respective products. However, the experts mentioned certain requirements so that Field Tests are efficient. That is, EP2 suggested that Lab Tests should be applied as a preceding measure, while EP5 remarked that successful Field Tests demand a well-functioning, robust and self-explanatory prototype for a valid and fruitful testing. Furthermore, EP3 noted that Field Tests should not exclusively focus on assessing the usability, as thereby further influence factors on the users’ product acceptance and application would be neglected. In addition, three of the five experts deemed the User Experience Test as suitable for the AAL field and stated a good applicability with elderly participants. EP4 reported that the technique delivers useful information on how well the functionalities of the developed technologies are accepted. EP5, however, remarked that the User Experience Test was more successful for products with a specific purpose and short-term application, as opposed to products that aim at changing a user’s complete lifestyle and/or behaviour. The Out-of-the-Box test (EP4 and EP5), the Tree Test technique (EP1 and EP4) as well as the Click Stream Analysis (EP1 and EP4) were also thought applicable to AAL projects, while Card Sorting only received one positive feedback (EP4).

4.5 Support Methods

Finally, looking at support methods, Fig. 5 shows that the Personas technique (67%), the Thinking Aloud technique (63%) and Audio/Video recording (33%) were applied by at least one third of the projects. The familiarity ratings showed furthermore that, except for Offering Maps, most of the support methods were familiar to participants.

Comparing the results listed in Tables 12, 13 and 14, it can be seen that the preparatory effort for Personas and Audio/Video recordings was perceived as moderate, while Thinking Aloud was rated with a moderately low level of preparatory effort. Regarding the financial effort, both the Personas technique (mean 1.72) and the Thinking Aloud technique (mean 2.00) received moderately low scores, while Audio/Video recording was perceived as moderate (mean 3.00). A further notable difference can be seen for the evaluation effort, which was rated high for Audio/Video recording, moderately high for Thinking Aloud and moderate for Personas. As for the fun factor, both the Personas technique with a mean score of 2.50 and the Audio/Video recording with a mean score of 2.44 achieved lower ratings than the Thinking Aloud technique with a mean rating of 3.41. All three techniques received similar recommendation ratings.

All experts explained that in their projects Personas were utilized to create a common conception of the potential end users. To this end, EP3 emphasized that Personas should always be based on scientifically substantiated data so as to avoid invalid assumptions. However, none of the experts reported that the Personas were evaluated with real end users, which would be reasonable according to EP5. Also the Thinking Aloud technique was attested good applicability for the use with older adults (EP4 and EP5), although EP2 reported that participants may be uncomfortable with the method. For the Audio/Video recording, EP2, EP4 and EP5 stated consistently that older adults often refuse to be recorded, which raises additional ethical questions.

4.6 Some General Feedback on UCD in AAL

During the final part of the interview study, experts had the possibility to state concluding remarks regarding UCD in AAL and the application of UCD methods with elderly users, allowing for the identification of challenges and barriers. Both EP1 and EP3 mentioned that limited financial and time resources in AAL development projects often hinder the application of several suitable UCD methods. Also, the physical and mental conditions of elderly participants complicate the use of some UCD techniques. EP3 added that the application of UCD methods within the development of AAL technologies often demands a higher sensitivity from the developers as it is the case for technologies that do not touch upon personal privacy or the health state of users. Consequently, the utilization of UCD techniques in the AAL field is often more labour-intensive and time consuming. A further barrier identified by EP3 concerns the often varying interpretation and application of UCD methods by different professional disciplines, which leads to inconsistencies. In this context, EP1 recommends a better identification and listing of suitable UCD methods to be used in AAL so as to provide an overview of existing methods and information on their correct application. EP3 gave warning that such a list should not aim at being generally applicable as so far there is still no commonly accepted understanding of the scope AAL and AAL technologies should cover.

EP1 further noted the necessity of adapting the selected UCD techniques to the elderly participants and suggested to apply the techniques in an informal atmosphere so as to not overwhelm the participants with the specifics of the respective technique. As a concluding remark, EP2 suggested to move from UCD to Human-Centered Design as this methodology places an even greater emphasize on the special needs and preferences of the users and thus would better comply with the requirements inherent to the AAL field.

5 Discussion

Overall, our study results show that the AAL field uses many rather generic UCD techniques such as interviews, focus group discussions, field tests or observations. Yet, as all of them require direct interaction and collaboration with elderly participants, it was also shown that the commitment to include potential end users during the development processes is present in the AAL community. A surprising result of our study is the rather low familiarity with more specific UCD methods. This applies especially to those techniques which were emphasized by the experts but not considered by the participating AAL projects. However, techniques highlighted by single experts have to be treated with caution, as for most cases they may only be applied in specific settings and for specific AAL technologies, which makes their generalizability difficult. Furthermore, we have seen that techniques which advise a very strict procedure are difficult to adhere to, for they often do not suit the specific application area or user profile of the respective AAL technology. This is in accordance with Newell et al. [21], who criticise the strict adherence to standard procedures while developing and designing with older adults. Generally, less standardized guidelines and more flexibility seems to be more suitable for the AAL field, and would furthermore support the underlying concept of UCD. Also, it may prevent some of the ‘tick-box attitudes’ present in other design and development communities [18].

Generally, several experts concluded that grounding the complete design and development process in user-centered or human-centered methodologies and incorporating these core concepts is more important than applying and adhering to specific techniques. Hallewell-Haslwanter et al. [14] detected a similar attitude within their study and reported of other European research projects having received similar comments.

In line with Eisma et al. [8] and Newell et al. [22], several experts stressed the need to adapt the traditional UCD approaches and techniques to better support the interaction with older people. In particular, it was deemed important that designers and developers empathize with potential end users, which includes the understanding of peoples’ emotional states, their specific life situation and their surrounding environment. Compatible with this viewpoint, Still and Crane [29] consider the emotional assessment during the user’s interaction with the product as crucial and therefore recommend emotion heuristics or enjoyability surveys as further complementary techniques.

Yet, even with appropriate UCD methods and techniques for the AAL field being available, the resources are often limited, which may bring all UCD efforts to an abrupt ending. Several experts we talked to reported resource scarcity on both the developer as well as the participant side.

Damodaran [4] as well as Stenmark et al. [28] identified limited resources as a general barrier for the involvement of users into product design and development processes. Thus experts reported the application of those UCD techniques that are the most cost-effective or the least labour-intensive, and not those that are the most suitable.

Another difficulty highlighted by our results concerns the physical and mental strains caused by certain techniques, which may inhibit analyses. Hallewell-Haslwanter [14] and Fitzpatrick [13] noted similar findings in their studies.

In summary, while these results are based on only 27 AAL projects and 5 expert opinions they do cover a big part of the current work conducted in this field and its implementation of UCD techniques. Further it may be argued that the sample size equals those of previous investigations, such as Hallewell-Haslwanter et al. [14] or Hornung-Prähauser et al. [15]. Consequently, we consider these results to show a robust trend supporting previous work.

6 Conclusion and Future Outlook

The aim of this study was to investigate to what extent UCD is applied within the development of elderly focused AAL technologies and how expedient this implementation is perceived. Results show that AAL projects primarily apply techniques which are popular and well-known in the design and development community but not specific to UCD. While the evaluation of these techniques (e.g., interviews, focus group discussions, field tests, observations) underlined their applicability and appropriateness for the AAL field, several experts recommended the use of some of the more UCD specific techniques, indicating a need for better dissemination. A distinct conceptualisation of UCD techniques that are generally applicable for the development of AAL technologies was, however, considered unrealistic, given the multifaceted characteristics of both the AAL technologies and the end users. Nonetheless, investigating the suitability of distinct UCD techniques for the development of a certain category of AAL technology and a thoroughly selected user group, should be considered an important piece of future work. If applied to a diverse set of technologies and user groups, this could eventually lead to a toolkit providing developers and designers with information on which UCD techniques are appropriate for which specific product and/or user group. Furthermore research should include alternative end users as well as relatives. In this whole context, the cultural and country-related peculiarities as, for example, the specifics of the different European health and social systems, the family and care situations, or the public support given to product developments in the field of AAL, need to be considered.

Our results also revealed the need for a certain compliance with the core values of the UCD or HCD methodology, noting that they are considered more important than adhering to predefined techniques. This would allow AAL developers to work user-centered and achieve valuable outcomes independently from specific techniques and procedures. In order to further distribute and endorse such approaches, activities on a regional or national level, comparable to for instance the efforts the European Union puts into the support of education and training for researchers in the field of Gerontechnology [25], would definitely benefit the development of AAL technologies.

Overall, we believe the results presented in this paper provide a general overview of the status quo regarding the use of UCD techniques in AAL, yet further studies with a similar focus are recommended. Those could for exampled gain additional insights by investigating UCD approaches of developers which operate outside the radar of the AAL JP community. Therefore, a detailed market analysis, which should go beyond what is currently happening in this field in Europe, is necessary. Global initiatives like the WHO funded Global Cooperation on Assistive Technology (GATE), which also provides the Priority Assistive Products List (APL), could serve as a reference point.

Also, gathering information on the use of UCD from those solution providers, that were able to develop successful products without the support of funding programs or other public initiatives, would be interesting. Considering the approaching end of the AAL JP in 2020, this could produce valuable insights with respect to the future development of European AAL technologies.

It is likely that the barriers for introducing AAL technologies will decrease, as modern technology becomes ever more established in our daily lives - even in those of the elderly. However, if we want for these solutions to serve the needs of the actual end users, the design and development processes have to be altered so as to better integrate the feedback of this distinct target population.

References

Astell, A.: Technology and fun for a happy old age. In: Sixsmith, A., Gutman, G. (eds.) Technologies for Active Aging. International Perspectives on Aging, vol. 9, pp. 169–187. Springer, Boston (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8348-0_10

Calvaresi, D., Cesarini, D., Sernani, P., Marinoni, M., Dragoni, A.F., Sturm, A.: Exploring the ambient assisted living domain: a systematic review. J. Ambient Intell. Hum. Comput. 8(2), 239–257 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-016-0374-3

Czaja, S.J., Boot, W.R., Charness, N., Rogers, W.A.: Designing for Olderadults: Principles and Creative Human Factors Approaches. CRC Press (2019)

Damodaran, L.: User involvement in the systems design process-a practical guide for users. Behav. Inf. Technol. 15(6), 363–377 (1996)

Dózsa, C., Mollenkopf, H., Uusikylä, P.: Final evaluation of the ambient assisted living joint programme (2013)

Dwivedi, S.K.D., Upadhyay, S., Tripathi, A.: A working framework for the user-centered design approach and a survey of the available methods. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2(4), 12–19 (2012)

ECFIN, ECD: The 2018 ageing report: economic and budgetary projections for the 28 EU member states (2016–2070) (2015)

Eisma, R., Dickinson, A., Goodman, J., Syme, A., Tiwari, L., Newell, A.F.: Early user involvement in the development of information technology-related products for older people. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 3(2), 131–140 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-004-0092-z

Fisk, D., Rogers, W., Charness, N., Czaja, S., Sharit, J.: Principles and creative human factors approaches (2009)

Glende, S.: Entwicklung eines Konzepts zur nutzergerechten Produktentwicklung mit Fokus auf die Generation Plus. Ph.D. thesis, Technische Universität Berlin (2010)

Hallewell Haslwanter, J.D., Fitzpatrick, G.: The development of assistive systems to support older people: issues that affect success in practice. Technologies 6(1), 2 (2018)

Hamblin, K.A.: Active Ageing in the European Union: Policy Convergence and Divergence. Palgrave Macmillan, London (2013). https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137303141

Haslwanter, J.D.H., Fitzpatrick, G.: Why do few assistive technology systems make it to market? The case of the \(HandyHelper\) project. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 16(3), 755–773 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-016-0499-3

Hallewell Haslwanter, J.D., Neureiter, K., Garschall, M.: User-centered design in AAL. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 19(1), 57–67 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-018-0626-4

Hornung-Prähauser, V., Wieden-Bischof, D., Willner, V., Selhofer, H.: Methoden zur geschäftsmodell-entwicklung für aal-lösungen durch einbeziehung der endanwenderinnen (2015)

Lazar, J., Feng, J.H., Hochheiser, H.: Research Methods in Human-Computer Interaction. Morgan Kaufmann (2017)

Leist, A., Ferring, D.: Technology and aging: inhibiting and facilitating factors in ICT use. In: Wichert, R., Van Laerhoven, K., Gelissen, J. (eds.) AmI 2011. CCIS, vol. 277, pp. 166–169. Springer, Heidelberg (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-31479-7_26

Lindsay, S., Jackson, D., Schofield, G., Olivier, P.: Engaging older people using participatory design. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1199–1208 (2012)

Maguire, M.: Methods to support human-centered design. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 55(4), 587–634 (2001)

Neves, B.B., Vetere, F.: Ageing and emerging digital technologies. In: Neves, B.B., Vetere, F. (eds.) Ageing and Digital Technology, pp. 1–14. Springer, Singapore (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3693-5_1

Newell, A., Arnott, J., Carmichael, A., Morgan, M.: Methodologies for involving older adults in the design process. In: Stephanidis, C. (ed.) UAHCI 2007. LNCS, vol. 4554, pp. 982–989. Springer, Heidelberg (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-73279-2_110

Newell, A.F., Carmichael, A., Gregor, P., Alm, N., Waller, A.: Information technology for cognitive support. In: Human-Computer Interaction, pp. 69–86. CRC Press (2009)

Queirós, A., Santos, M., Dias, A., da Rocha, N.P.: Ambient assisted living: systems characterization. In: Queirós, A., Rocha, N.P. (eds.) Usability, Accessibility and Ambient Assisted Living. HIS, pp. 49–58. Springer, Cham (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91226-4_3

Shneiderman, B., Plaisant, C., Cohen, M., Jacobs, S., Elmqvist, N., Diakopoulos, N.: Designing the User Interface: Strategies for Effective Human-Computer Interaction. Pearson (2016)

Sixsmith, A.: Technology and the challenge of aging. In: Sixsmith, A., Gutman, G. (eds.) Technologies for Active Aging. International Perspectives on Aging, vol. 9, pp. 7–25. Springer, Boston (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8348-0_2

Sixsmith, A., Mihailidis, A., Simeonov, D.: Aging and technology: taking the research into the real world. Public Policy Aging Rep. 27(2), 74–78 (2017)

Spinsante, S., et al.: The human factor in the design of successful ambient assisted living technologies. In: Ambient Assisted Living and Enhanced Living Environments, pp. 61–89. Elsevier (2017)

Stenmark, P., Tinnsten, M., Wiklund, H.: Customer involvement in product development: experiences from Scandinavian outdoor companies. Procedia Eng. 13, 538–543 (2011)

Still, B., Crane, K.: Fundamentals of User-Centered Design: A Practical Approach. CRC Press (2017)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Barth, S., Weichelt, R., Schlögl, S., Piazolo, F. (2020). UCD in AAL: Status Quo and Perceived Fit. In: Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Gao, Q., Zhou, J. (eds) HCI International 2020 – Late Breaking Papers: Universal Access and Inclusive Design. HCII 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 12426. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60149-2_35

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60149-2_35

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-60148-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-60149-2

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)