Abstract

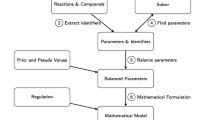

Bacterial infections are among the major causes of mortality in the world. Despite the social and economical burden produced by bacteria, the number of new drugs to combat them increases very slowly due to the cost and time to develop them. Thus, innovative approaches to identify efficiently drug targets are required. In the absence of genetic information, chokepoint reactions represent appealing drug targets since their inhibition might involve an important metabolic damage. In contrast to the standard definition of chokepoints, which is purely structural, this paper makes use of the dynamical information of the model to compute chokepoints. This novel approach can provide a more realistic set of chokepoints. The dependence of the number of chokepoints on the growth rate is assessed on a number of metabolic networks. A software tool has been implemented to facilitate the computation of growth dependent chokepoints by the practitioners.

This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities [ref. Medrese-RTI2018-098543-B-I00], and by the Medical Research Council, UK, MR/N501864/1.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bannerman, B.P., et al.: Analysis of metabolic pathways in mycobacteria to aid drug-target identification. bioRxiv (2019). https://doi.org/10.1101/535856

Burgard, A.P., Vaidyaraman, S., Maranas, C.D.: Minimal reaction sets for escherichia coli metabolism under different growth requirements and uptake environments. Biotechnol. Prog. 17(5), 791–797 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1021/bp0100880

Glont, M., et al.: Biomodels: expanding horizons to include more modelling approaches and formats. Nucleic Acid Res. 46(D1), D1248–D1253 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx1023

Gudmundsson, S., Thiele, I.: Computationally efficient flux variability analysis. BMC Bioinf. 11(1), 489 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-11-489

Heiner, M., Gilbert, D., Donaldson, R.: Petri nets for systems and synthetic biology. In: Bernardo, M., Degano, P., Zavattaro, G. (eds.) SFM 2008. LNCS, vol. 5016, pp. 215–264. Springer, Heidelberg (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-68894-5_7

Karp, P.D., et al.: The BioCyc collection of microbial genomes and metabolic pathways. Briefings Bioinf. 20(4), 1085–1093 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbx085

Lamberti, L.M., et al.: Breastfeeding for reducing the risk of pneumonia morbidity and mortality in children under two: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S18

Mackie, A., Keseler, I.M., Nolan, L., Karp, P.D., Paulsen, I.T.: Dead end metabolites - defining the known unknowns of the e. coli metabolic network. PLoS ONE 8(9), e75210 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075210

Mazurek, S.: Pyruvate kinase type M2: a key regulator of the metabolic budget system in tumor cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 43(7), 969–980 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2010.02.005

Munger, J., et al.: Systems-level metabolic flux profiling identifies fatty acid synthesis as a target for antiviral therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 26(10), 1179–1186 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1500

Murata, T.: Petri nets: properties, analysis and applications. Proc. IEEE 77(4), 541–580 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1109/5.24143

Murima, P., McKinney, J.D., Pethe, K.: Targeting bacterial central metabolism for drug development, November 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.08.020

Orth, J.D., et al.: A comprehensive genome-scale reconstruction of Escherichia coli metabolism-2011. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7(1), 535 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/msb.2011.65

Orth, J.D., Thiele, I., Palsson, B.O.: What is flux balance analysis?, March 2010. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1614

Rahman, S.A., Schomburg, D.: Observing local and global properties of metabolic pathways: ‘load points’ and ‘choke points’ in the metabolic networks. Bioinformatics (Oxford, Engl.) 22(14), 1767–1774 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btl181

Raman, K., Vashisht, R., Chandra, N.: Strategies for efficient disruption of metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis from network analysis. Mol. BioSyst. 5(12), 1740–1751 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1039/B905817F

Segre, D., Vitkup, D., Church, G.M.: Analysis of optimality in natural and perturbed metabolic networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99(23), 15112–15117 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.232349399

Singh, S., Malik, B.K., Sharma, D.K.: Choke point analysis of metabolic pathways in E. histolytica: a computational approach for drug target identification. Bioinformation 2(2), 68–72 (2007). https://doi.org/10.6026/97320630002068

Varma, A., Palsson, B.Ø.: Metabolic flux balancing: basic concepts, scientific and practical use. Nat. Biotechnol. 12(10), 994–998 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1094-994

WHO: WHO | Causes of death. WHO (2018)

Zhang, R., Lin, Y.: DEG 5.0, a database of essential genes in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 37(suppl\_1), D455–D458 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkn858

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

A Appendix

The software tool findCPcli developed in this work consists of a command line application that, given an input model provided by the user, computes the sizes of the sets of non-reversible reactions, reversible reactions, dead reactions and chokepoint reactions for different values of \(\gamma \). The results are saved in a spreadsheet file with a format similar to the one presented in Table 3.

The tool findCPcli is distributed as a Python package and requires Python 3.5 or a higher version. The source can be found at github.com/findCP/findCPcli. findCPcli can be installed with the pip package management tool:

pip install findCPcli

Once installed, the results for a given SBML model can be computed running:

findCPcli -i

where:

-

is the path of the input SBML model file to be used. The supported file formats are .xml, .json and .yml.

is the path of the input SBML model file to be used. The supported file formats are .xml, .json and .yml. -

is the path of the spreadsheet file that will be saved with the results computed on the model. The available file formats for the spreadsheet file are .xls, .xlsx and .ods.

is the path of the spreadsheet file that will be saved with the results computed on the model. The available file formats for the spreadsheet file are .xls, .xlsx and .ods.

When the above command is executed, the command line application will inform about the task that will be computed. If the task finishes successfully and the spreadsheet file has been saved, the application will inform about it and will end the execution.

Further information about the operations provided by the application can be found by executing: findCPcli -h.

B Appendix

Table 3 reports the sizes of the sets of reversible, non-reversible, dead and chokepoint reactions for several constraint-based models of the Biomodels repository [3]. All the results were computed by the tool findCPcli. The maximum CPU time was 82.776 s to compute the results of model MODEL1507180017 in an Intel Core i5-9300H CPU @ 2.40 GHz \(\times \) 8.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Oarga, A., Bannerman, B., Júlvez, J. (2020). Growth Dependent Computation of Chokepoints in Metabolic Networks. In: Abate, A., Petrov, T., Wolf, V. (eds) Computational Methods in Systems Biology. CMSB 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 12314. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60327-4_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60327-4_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-60326-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-60327-4

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)

is the path of the input SBML model file to be used. The supported file formats are .xml, .json and .yml.

is the path of the input SBML model file to be used. The supported file formats are .xml, .json and .yml. is the path of the spreadsheet file that will be saved with the results computed on the model. The available file formats for the spreadsheet file are .xls, .xlsx and .ods.

is the path of the spreadsheet file that will be saved with the results computed on the model. The available file formats for the spreadsheet file are .xls, .xlsx and .ods.