Abstract

The Japanese degree adverb kasukani can be combined with a sense-related gradable predicate, such as amai ‘sweet’ or kaoru ‘smell’, but it cannot usually co-occur with an emotive predicate, such as odoroi-teiru ‘surprised’. However, if there is a sense-related expression that is structurally placed at a higher position, kasukani can combine with an emotive predicate. Building on the idea of Sawada (2021), I will first show that kasukani is mixed content (McCready 2010; Gutzmann 2011) in that it not only denotes a low scalar meaning in the at-issue component, but also implies that the judge (typically the speaker) has measured its degree based on their own senses (e.g., vision, smell, taste, or hearing) at the level of conventional implicature (CI)(e.g., Grice 1975; Potts 2005). I will then argue that the projective property of the CI meaning of kasukani allows kasukani to be used to measure the degree of emotion through a sense-based expression, such as mie-ru ‘look’. I will also compare kasukani to English faintly, which can be used to measure the degree of emotion directly or measure the degree of emotion indirectly via a sense-based expression and explain the differences between the two by positing different CI components. This study demonstrates that the multidimensional approach to meaning can successfully explain the concord relationship between a sense-based minimizer and sense-related expression.

I am grateful to Daisuke Bekki, Ikumi Imani, Chris Kennedy, Hideki Kishimoto, Kenta Mizutani, David Oshima, Harumi Sawada, Jun Sawada, Koji Sugisaki, Eri Tanaka, and the reviewers of LENLS 18 for their valuable comments and suggestions. Parts of this paper were presented at the seminar at Kwansei Gakuin University and the ICU Linguistics Colloquium, and I also thank the audiences for their valuable discussions. This study is based on work supported by the JSPS KAKENHI Grant (21K00525, 22K00554) and the NINJAL collaborative research project “Evidence-based Theoretical and Typological Linguistics” All remaining errors are, of course, my own.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

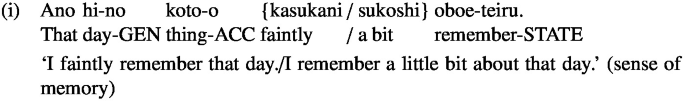

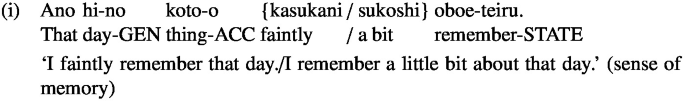

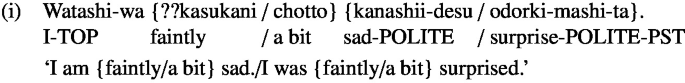

Furthermore, kasukani can also be used to measure the degree of memory:

.

- 2.

In this study, I do not consider the experiential component of kasukani a presupposition. It is the judge’s personal experience (typically a speaker’s experience), not something that is shared between a speaker and a hearer.

- 3.

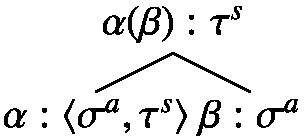

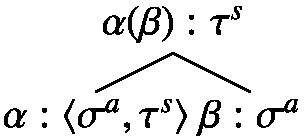

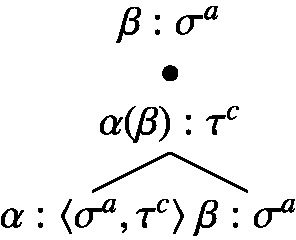

The following figure shows the shunting application:

(i) The shunting application (Based on McCready 2010)

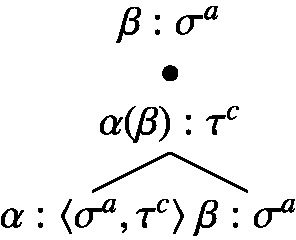

The shunting application is different from Potts’ (2005) CI application, where it is resource-sensitive. Potts’s CI application is resource-insensitive, as shown in (ii):

(ii) CI application (Potts 2005)

The superscript c represents the CI type, which is used for CI application. Here, the \( \alpha \) of \(\langle \sigma ^a, \tau ^c\rangle \) takes a \(\beta \) of type \(\sigma ^a\) and returns \(\tau ^c\). Simultaneously, a \(\beta \) is passed on to the mother node.

- 4.

Here, the CI of kasukani is taken as information related to the act of how the judge is weighing the degree in question. Kasukani is not evaluative in the sense that it does not express the speaker’s attitude toward the degree of the at-issue. Rather, the act of measurement based on the sense and measurement at the at-issue level are taking place simultaneously. This point is different from the mixed content Kraut, which denotes German in the at-issue domain and additionally conveys that the speaker has a negative attitude toward German people (McCready 2010; Gutzmann 2011).

- 5.

Here, I consider that the unmodified adjective sweet/amai is of the same type as the usual gradable adjective, and no judge variable (j) is assumed. In positive adjective sentences, sweet/amai is evaluated in relation to the speaker’s minimum standard, and I assume that the standard is introduced by a positive form (pos) or a degree modifier. This is where the judgment is made. In comparative sentences, the unmodified adjective is attached to the comparative morpheme.

- 6.

It seems that the minimum standard of amai ‘sweet’ is context-dependent (person-dependent), and is different in nature from the minimum standard of typical absolute gradable predicates, such as English bent and Japanese magat-teiru ‘bent’. Whether something is sweet is judged based on whether the degree of sweetness exceeds the minimum standard of sweetness, but as people have different senses of taste, the minimum standard is not absolute in a physical sense. It may be that sense-related adjectives belong to a new type of gradable predicate (i.e., possessing the features of both relative and absolute adjectives).

- 7.

I thank Kenta Mizutani for the valuable discussion regarding this point.

- 8.

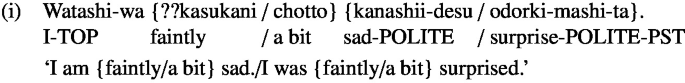

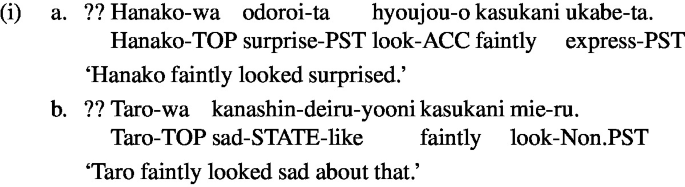

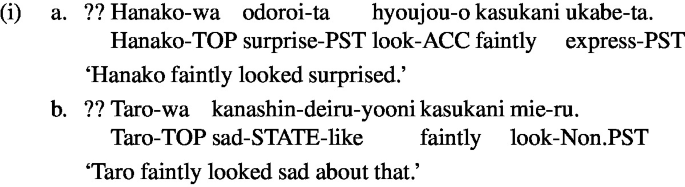

Even if the subject is in the first person, kasukani ‘faintly’ cannot modify an emotive predicate:

.

- 9.

Note that if we place kasukani before the main predicate, the sentences become odd:

.

- 10.

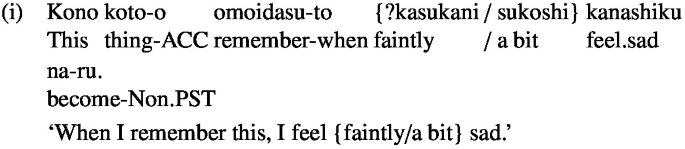

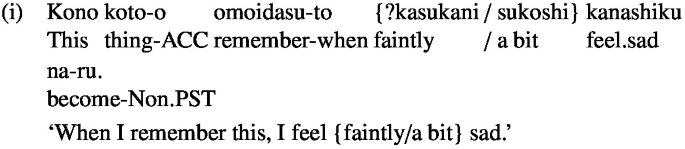

A reviewer provided me with the following example, which does not include a perception verb in the main clause:

This sentence seems to be relatively natural because the verb omoidasu ‘remember’ is present in the when-clause, which is concerned with memory and experience. However, the sentence may still sound a bit unnatural because it is not clear how the speaker relates the degree of sadness and memory. A more detailed investigation will be necessary to clarify the possible patterns of indirect measurement.

- 11.

Faintly basically cannot combine with non-sense/emotion-related adjectives (i.e., #faintly expensive, #faintly tall).

References

Amaral, P., Roberts, C., Smith., A.E.: Review of the logic of conventional implicatures by Chris Potts. Linguist. Philos. 30(6), 707–749 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-008-9025-2

Cresswell, M.J.: The semantics of degree. In: Partee, B. (ed.) Montague Grammar, pp. 261–292. Academic Press, New York (1976)

Grice, P.H.: Logic and conversation. In: Cole, P., Morgan, J. (eds.) Syntax and Semantics III: Speech Acts, pp. 43–58. Academic Press, New York (1975)

Gutzmann, D.: Expressive modifiers & mixed expressives. In: Bonami, O., Hofherr, P. (eds.) Empirical Issues in Syntax and Semantics 8, pp. 123–141 (2011)

Harris, J.A., Potts, C.: Perspective-shifting with appositives and expressives. Linguist. Philos. 32(6), 523–552 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-010-9070-5

Kennedy, C., McNally, L.: Scale structure, degree modification, and the semantics of gradable predicates. Language 81(2), 345–381 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2005.0071

Kennedy, C., Willer, M.: Evidence, attitudes, and counterstance contingency: Toward a pragmatic theory of subjective meaning, manuscript, University of Chicago (2019)

Klein, E.: Comparatives. In: von Stechow, A., Wunderlich, D. (eds.) Semantik: Ein Internationales Handbuch der Zeitgenossischen Forschung, pp. 673–691. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin (1991)

McCready, E.: Varieties of conventional implicature. Semant. Pragmat. 3, 1–57 (2010). https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.3.8

Ninan, D.: Taste predicates and the acquaintance inference. In: Snider, T., D’Antonio, S., Weigand, M. (eds.) Proceedings of SALT 24, pp. 290–304 (2014). https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v24i0.2413

Pearson, H.: A judge-free semantics for predicates of personal taste. J. Semant. 30(1), 103–154 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffs001

Potts, C.: The Logic of Conventional Implicatures. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2005). https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199273829.001.0001

Potts, C.: The expressive dimension. Theoret. Linguist. 33, 165–197 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1515/TL.2007.011

Roberts, R.C.: Emotions: An Essay in Aid of Moral Psychology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2003)

Sawada, O.: Pragmatic aspects of scalar modifiers. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Chicago (2010)

Sawada, O.: Pragmatic Aspects of Scalar Modifiers: The Semantics-Pragmatics Interface. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198714224.001.0001

Sawada, O.: Scalar properties of Japanese and English sense-based minimizers. Proc. Linguist. Soc. Am. 6(1), pp. 433–447 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v6i1.4979

Seuren, P.: The comparative. In: Kiefer, F., Ruwet, N. (eds.) Generative Grammar in Europe, pp. 528–64. Reidel, Dordrecht (1973)

von Stechow, A.: Comparing semantic theories of comparison. J. Semant. 3, 1–77 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/3.1-2.1

Willer, M., Kennedy, C.: Assertion, expression, experience. Inquiry, 1–37 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2020.1850338

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Sawada, O. (2023). Interpretations of Sense-Based Minimizers in Japanese and English: Direct and Indirect Sense-Based Measurements. In: Yada, K., Takama, Y., Mineshima, K., Satoh, K. (eds) New Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence. JSAI-isAI 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 13856. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-36190-6_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-36190-6_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-36189-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-36190-6

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)