Abstract

This study investigates semantic properties of Japanese mono-nara conditionals that obligatorily encode subjunctivity of the antecedent. Considering the existence of two distinct negative meanings conveyed by mono-nara conditionals, we attempt to explain this flexible negativity from the semantics of mono-nara and the associated modal in a compositional manner. The analysis contributes to providing a cross-linguistically interesting strategy for deriving negativity of conditional antecedents.

The paper has profited from discussions with Muyi Yang. Financial support was provided by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 21K13000) to the first author. All errors are of course our own.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

We represent the subjunctive marker as “[y]oo” throughout this paper. The form -oo occurs when the marker attaches to verbal bases ending a consonant, whereas yoo is used when it follows verbal bases ending a vowel. Note also that the conditional morpheme nara cannot follow [y]oo without the intervening light noun mono ‘thing’ (e.g., “Taro-ga ko-yoo *(mono) nara, ...” ‘If Taro comes, ...’).

- 2.

The example is similar to what [6] refers to as the future less vivid conditionals, which have the implicature that the actual world is more likely to become a \(\lnot p\)-world than a p-world.

- 3.

Using the conditional morpheme tara is more preferable than nara in (5a), which would be due to the difference in what [7] calls the notion of “settledness”, i.e. the determinedness of the truth-value of a proposition at the time of utterance. Refer to [2] for details on the differences between the two.

- 4.

This may be a surprising and interesting fact from a typological perspective of modals, given that almost all the modal expressions in Japanese (e.g., nitigainai ‘(epistemic) must’, nakerebanaranai ‘(deontic) must’, kamosirenai ‘(epistemic) may’, temoii ‘(deontic) may’, etc.) have a fixed modal flavors. See [16] and [9] for properties of Japanese modals and [8] and [15] for possible explanations for the obligatory fixed flavor.

- 5.

It is worth noting that sentences with the prioritizing/deontic use of [y]oo generally requires the speech act (or illocutionary force) of the utterance to be promissive or exhortative, both of which includes the speaker as the first-person subject [18]. However, we are hesitant to regard [y]oo itself as a marker of promissive or exhortative force since sentences with [y]oo can also be used as imperatives with the second-person subject (even though the examples are relatively few). We will thus focus only on the semantic (i.e., the modal) aspect of [y]oo and put aside the question of how the use of [y]oo affects the discourse effect of the utterance.

- 6.

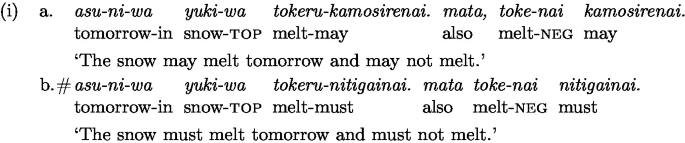

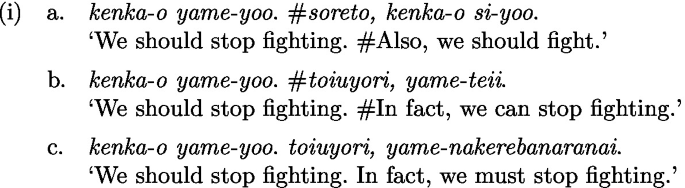

The relevant examples are shown below.

.

- 7.

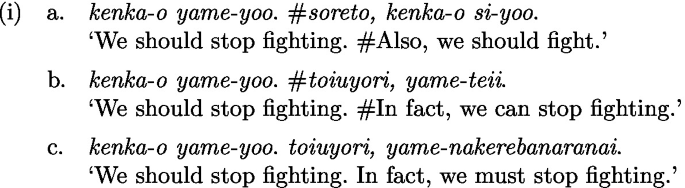

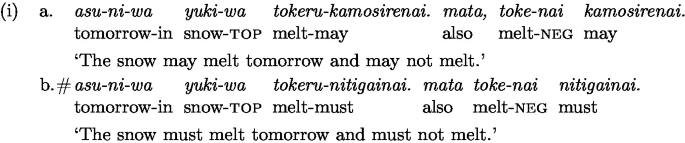

The definition in (10) also holds in the case of deontic [y]oo:

The inconsistency in (ia, b) indicates that deontic [y]oo encodes some sort of necessity, and the contrast found in (ib) and (ic) shows that the necessity is relatively weak.

- 8.

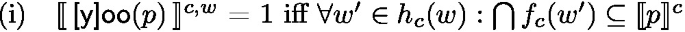

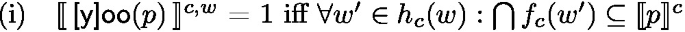

We could also define the meaning of [y]oo under other frameworks for modals. For instance, if we adopt [23]’s version of weak necessity, [y]oo(p) is true iff p follows from the relevant considerations \(f_c\) at every \(w' \in h_c(w)\), as represented below. \(h_c\) is a contextually supplied function that selects a set of relevant (closest) worlds that are preferred in c—most normal, expected, desirable, etc.

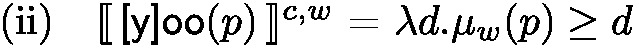

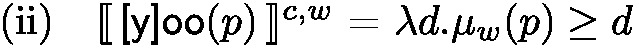

On the other hand, under degree-based approaches including [13] and [21], the meaning of weak necessity [y]oo is not quantification over possible worlds, but is certain degrees, as in (ii).

The underlying scale that the measure function \(\mu \) in (ii) operates on includes measures of probability of achieving a certain goal or priority. We leave closer exploration of the issue as to which approach is preferable for the analysis of [y]oo for future research.

- 9.

- 10.

To the best of our knowledge, this scopal relation between modals and negation has not been attested in Japanese. The situation in Japanese with respect to the scopal relation would be more complex than English because most modal expressions in Japanese have a complex structure consisting of multiple lexical items (cf. [8]) and thus leaving a possibility of having different syntactic/semantic properties than modals that are defined as a single lexical item.

- 11.

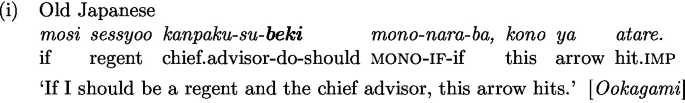

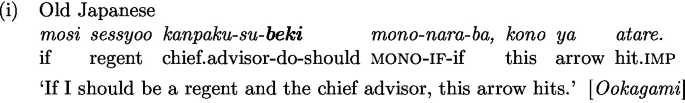

One caveat here is that as shown in (i), the deontic modal beki ‘should’ seems to able to occur with mono-nara in Old Japanese.

It is unclear whether (i) was uttered in the context where it was unlikely that the speaker would be a regent or the chief advisor. (Undesirability should be irrelevant here because it would be desirable for the speaker (i.e. Fujiwara-no Michinaga, the Japanese statesman who reigned the Imperial capital in Kyoto) to obtain the high rank positions.) Further investigation of mono-nara conditionals in Old Japanese is an interesting topic, but it is beyond the scope of this article.

- 12.

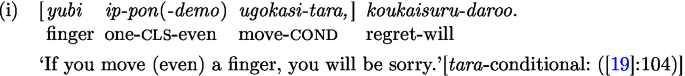

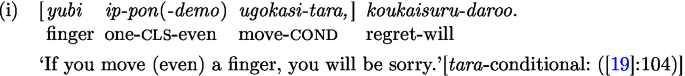

[19] reported that the minimizer expression yubi ip-pon ugokasu ‘move a finger’ is licensed in the antecedent of the tara-conditional, as in (i).

The availability of the minimizer interpretation in (i) indicates that the tara-conditional, unlike other Japanese conditionals, behaves like the if-conditional in English regarding licensing of minimizers. This peculiarity of the tara-conditional needs to be explained, but it is beyond the scope of the current paper.

- 13.

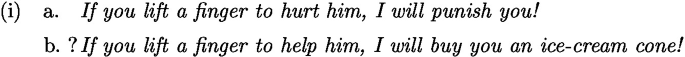

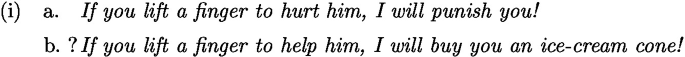

Notice also that [4] report that English conditional threats can license minimizers more naturally than conditional promises, as shown in (i).

The contrast in (i) can be captured under the proposed analysis in the current paper. Conditional threats are similar to the mono-nara conditional in the sense that in both cases the speaker expresses a negative attitude toward the proposition in the antecedent clause. In (ia), the speaker believes that it is unacceptable that the hearer hurts him. Under the current analysis, it may be possible to hypothesize that the minimizer expression lift a finger in (ia) is licensed by negation at the presuppositional level, like the mono-nara conditional.

References

Akatsuka, N.: Dracula conditionals and discourse. In: Georgopolous, C., Ishihara, R. (eds.) Interdisciplinary Approaches to Language: Essays in Honour of S. Kuroda, pp. 25–37. Kluwer Academic Publishers, London (1991)

Arita, S.: Nihongo zyookenbun to ziseisetusei [Japanese Conditionals and Tensedness]. Kurosio Publishers, Tokyo (2007)

Condoravdi, C., Lauer, S.: Imperatives: meaning and illocutionary force. In: Empirical Issues in Syntax and Semantics, vol. 9, pp. 37–58 (2012)

Eckardt, R., Csipak, E.: Minimizers: towards pragmatic licensing. In: Csipak, E., Liu, M., Eckardt, R., Sailer, M. (eds.) Beyond änyänd ëver. New Explorations in Negative Polarity Sensitivity, 267–298. De Gruyter, Berlin (2013)

von Fintel, K., Iatridou, S.: How to say ought in foreign: the composition of weak necessity modals. In: Guéron, J., Lecarme, J. (eds.) Time and Modality. SNLT, vol. 75, pp. 115–141. Springer, Berlin (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8354-9_6

Iatridou, S.: The grammatical ingredients of counterfactuality. Linguist. Inquiry 31(2), 231–270 (2000)

Kaufmann, S.: Conditional truth and future reference. J. Semant. 22(3), 231–280 (2005)

Kaufmann, M.: What ‘may’ and ‘must’ may be in Japanese. In: Funakoshi, K., Kawahara, S., Tancredi, C.D. (eds.) Japanese/Korean Linguistics, p. 24. CSLI Publications, Stanford (2017)

Kaufmann, M., Tamura, S.: Japanese modality-possibility and necessity: prioritizing, epistemic, and dynamic. In: Jacobsen, W.M., Takubo, Y. (eds.) Handbook of Japanese Semantics and Pragmatics, pp. 537–585. de Gruyter, Berlin (2020)

Kratzer, A.: The notional category of modality. In: Eikmeyer, H.J., Rieser, H. (eds.) Words, Worlds, and Context, pp. 38–74. de Gruyter, Berlin (1981)

Kratzer, A.: Conditionals. Chicago Linguist. Soc. 22(2), 1–15 (1986)

Kuno, S.: The Structure of the Japanese Language. MIT Press, Cambridge (1973)

Lassiter, D.: Graded Modality: Qualitative and Quantitative Perspectives. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2017)

Lee, C.-B.: A study of negative conditionals in Korean: -\(takanun\) and \(esstakanun\). Lang. Res. 44(2), 299–318 (2008)

Mizutani, K., Ihara, S.: Decomposing the Japanese deontic modal hoo ga ii. In: Jeon, H.-S. (ed.) Japanese/Korean Linguistics 28 Online Proceedings. CSLI Publications, Stanford (2021)

Narrog, H.: Modality in Japanese: The Layered Structure of the Clause and Hierarchies of Functional Categories. John Benjamins, Amsterdam (2009)

Nevins, A.: Counterfactuality without past tense. In: Proceedings of the North East Linguistic Society, vol. 32, pp. 441–451 (2002)

Kenkyuukai, N.K.B.: Gendai nihongo bunpoo [Contemporary Japanese Grammar], vol. 4. Kurosio Publishers, Tokyo (2003)

Oda, T.: Degree constructions in Japanese. Doctoral dissertations, University of Connecticut (2008)

Ogihara, T.: The semantics of -ta in Japanese counterfactual conditionals. In: Crnic, L., Sauerland, U. (eds.) The Art and Craft of Semantics: A Festschrift for Irene Heim, vol. 2, pp. 1–21. MITWPL, Cambridge (2014)

Portner, P., Rubinstein, A.: Extreme and non-extreme deontic modals. In: Charlow, N., Chrisman, M. (eds.) Deontic Modality, pp. 256–282. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2016)

Rubinstein, A.: Weak necessity. Ms, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (2017)

Silk, A.: Weak and strong necessity modals: on linguistic means of expressing “a primitive concept OUGHT”. In: Dunaway, B., Plunkett, D. (eds.) Meaning, Decision, and Norms: Themes from the Work of Allan Gibbard. Michigan Publishing Services, to appear

Vander Klok, J., Hohaus, V.: Weak necessity without weak possibility: the composition of modal strength distinctions in Javanese. Semant. Pragmatics 13(12) (2020)

Yalcin, S.: Modalities of normality. In: Charlow, N., Chrisman, M. (eds.) Deontic Modality, pp. 230–55. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2016)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Ihara, S., Tatsumi, Y. (2023). The Duality of Negative Attitudes in Japanese Conditionals. In: Yada, K., Takama, Y., Mineshima, K., Satoh, K. (eds) New Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence. JSAI-isAI 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 13856. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-36190-6_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-36190-6_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-36189-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-36190-6

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)