Abstract

This paper argues that the semi-modal use of drohen ‘threaten’ in German, which roughly means that something undesirable is going to happen, has a modal as well as an evidential component. To this end, we first provide an argument against the purely temporal-aspectual analysis proposed by Reis (2005, 2007) [27, 28], and more generally, against a reductionist attempt to apply an analysis of prospective aspect (e.g. [4, 5]) to drohen. The crucial observation for establishing modality in the semantics of drohen is that when used in the present tense, it is incompatible with propositions entailing the negation of its prejacent, as is the case with epistemic modals. Evidence for evidentiality in drohen comes from its infelicity in contexts in which the prejacent is regarded as possible, but no concrete evidence is available. To capture these observations, we provide a semantics of drohen that contains both modal and evidential components in a framework that is an extension of Mandelkern’s (2019) [16] work, which draws on the notion of local context in the sense of Schlenker (2009) [30]. More specifically, we make local contexts time-sensitive to address different behaviors of drohen in the present and past tenses. The analysis is presented in a compositional setting based on Rullman & Matthewson’s (2018) [29] framework for tense-aspect-modality interactions.

I am grateful to two anonymous reviewers of the abstract, the participants in LENLS19, and one anonymous reviewer of this paper for their helpful comments and suggestions. For judgments of the constructed examples and comments on them, I am deeply indebted to Ingrid Kaufmann and Christian Klink. I am also grateful to Daniel Gutzmann, Klaus von Heusinger, Łukasz Jędrzejowski, Yoshiki Mori, Carla Umbach, and the other participants at Germanistik zwischen Köln und Tokio (GAKT) 6, where I presented a related talk on drohen, for their insightful comments and discussions. All errors are my own.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

By the prejacent of drohen, we mean what is denoted by the remainder of the sentence excluding drohen(i.e., the infinitival complement together with drohen’s subject). In other words, we assume that drohen takes semantic scope over the rest of the sentence. A more precise compositional setting is shown in Sect. 5.

- 2.

Strictly speaking, since [27, 28]’s original analysis makes reference to the initial state, as well as to the pre-states of the prejacent, it is not completely equivalent to our purely prospective reconstruction of the analysis. However, the original analysis should also predict that negated drohen-sentences imply the non-existence of pre-states of the prejacent due to the disjunctive reference to phases of the prejacent eventuality (the initial states or pre-states).

- 3.

The contingent relation covers not only causal links between events but also links based on agencies’ planning, prediction, intention, etc. (p. 16, [21]).

- 4.

- 5.

A time \(t_1\) abuts a time \(t_2\) (\(t_1 \scriptstyle \supset \subset \textstyle t_2\)) iff \(t_1\) precedes \(t_2\) (\(t_1 < t_2\)) and there is no \(t_3\) such that \(t_1< t_3 < t_2\).

- 6.

- 7.

See [10] for an overview and discussions of this topic.

- 8.

- 9.

Note that the context makes Max’s awareness of the question of whether it will rain soon explicit. As [32] points out, the use of epistemic modals requires the relevant agent’s belief to be sensitive to a question for which the prejacent is an answer or a partial answer (p. 316). For example, it is inappropriate to assert “Hank thinks it might be raining in Topeka” in a context in which the question of rain in Topeka never occurs to Hank while his belief is compatible with it raining there. However, the treatment of this belief-sensitivity of epistemic modals is beyond the scope of this paper.

- 10.

I thank one of the reviewers for pointing out this possibility.

- 11.

More precisely, \(t_c\) is used as a temporal argument of drohen due to its present tense. How semantic composition proceeds between drohen and the other elements in a sentence is illustrated below.

- 12.

Whether or how to shift the designated time for conditional antecedents is beyond the scope of this paper and is left for future research.

- 13.

- 14.

Unlike [23], which also posits a primitive evidence relation in the semantics of evidentials, no explicit evidence holder is represented in the present analysis. This is in order to deal with cases in which no evidence holder can be considered to be present. In the following example, the prejacent pertains to the concentration of oxygen a few million years ago, when no intellectual being that would have had some evidence of this eventuality could be assumed to have existed. In this case, we need an objective notion of evidence that is independent of the existence of evidence holders (cf. [1] for several objective notions regarding evidence).

.

- 15.

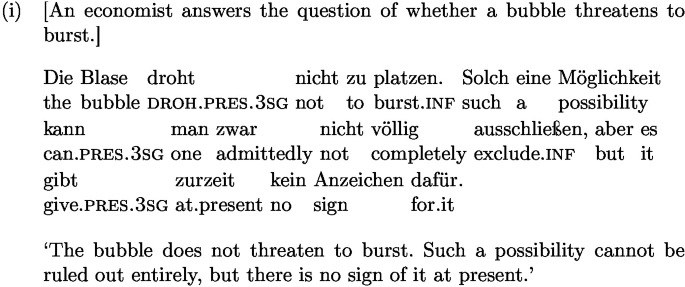

An anonymous reviewer raises a concern regarding whether the evidential component of drohen is an at-issue content, which can be the target of negation (cf. [23] for the non-at-issueness of evidential expressions in English and Cheyenne; but see also [20] and [9] for the at-issue behaviors of Japanese inferential evidentials and the German reportative sollen, respectively). The felicity of the following discourse shows that drohen’s evidential meaning can, in fact, be negated and should thus be located in the at-issue dimension:

The last two sentences in this discourse describe a situation in which the possibility of the prejacent becoming true is admitted, although there is no evidence for the prejacent. In other words, in this context, the modal condition is satisfied while the evidential condition is not. If drohen’s evidential meaning were in a non-at-issue dimension, the modal condition would be the only meaning that the negation (contributed by nicht) could target, so that the negated drohen-sentence would be incompatible with the following sentence. By contrast, our analysis predicts the felicity of (i) since the non-satisfaction of the evidential condition is sufficient for the truth of the negated drohen-claim.

- 16.

Such a sublexical treatment is also assumed in [29] for English modals.

- 17.

Simon Goldstein (p.c.) pointed out that if drohen did not tolerate embedding under other epistemic modals, that would provide evidence for its epistemic modal nature. Although his point seems to be correct, it doesn’t imply its inverse, at least in terms of type-driven semantic composition: Since modals are of type \(\langle \langle i,\langle st\rangle ,\langle i,\langle st\rangle \rangle \), they return objects of type \(\langle i,\langle st\rangle \rangle \) when applied to their prejacents of type \(\langle i,\langle st\rangle \rangle \); thus, it is predicted that they can scope under another modal element. In fact, occasional examples in which drohen occurs under epistemic modals can be found in the Deutsche Referenzkorpus (p. 263, [6]). What such sentences mean and how to capture them in a formal analysis is beyond the scope of this paper.

- 18.

Similarly, [14] argues that the semi-modal use of versprechen ‘promise,’ which is close to the semi-modal drohen in meaning and syntax, occupies the Asp\(_{\text {prospective}}\) head, which corresponds to our Asp\(_{\text {Ord}}\). Investigation into drohen’s precise syntactic position must be left for future research, however.

- 19.

evid is short for there is some concrete evidence.

- 20.

Here, we follow [29] in adopting a presuppositional treatment of tenses.

References

Achinstein, P.: The Book of Evidence. Oxford University Press, New York (2001)

Anvari, A., Blumberg, K.: Subclausal local contexts. J. Semant. 38(3), 393–414 (2021)

Barker, C.: Composing local contexts. J. Semant. 39(2), 385–407 (2022)

Bohnemeyer, J.: Aspect vs. relative tense: the case reopened. Nat. Lang. Semant. 32(3), 917–954 (2014)

Bowler, M.L.: Aspect and evidentiality. Ph.D. thesis, University of California Los Angeles (2018)

Colomo, K.: Modalität im Verbalkomplex. Ph.D. thesis, Ruhr-Universität Bochum (2011)

Condoravdi, C.: Temporal interpretation of modals: modals for the present and the past. In: Beaver, D., Martinez, L.C., Clark, B., Kaufmann, S. (eds.) The Construction of Meaning, pp. 59–88. CSLI Publications, Stanford (2002)

Egan, A., Hawthorne, J., Weatherson, B.: Epistemic modals in context. In: Preyer, G., Peter, G. (eds.) Contextualism in Philosophy: Knowledge, Meaning, and Truth, pp. 131–169. Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York (2005)

Faller, M.: Evidentiality below and above speech acts (2006). https://personalpages.manchester.ac.uk/staff/martina.t.faller/documents/Evidentiality.Above.Below.pdf

Green, M., Williams, J.N.: Moore’s Pradox: New Essays on Belief, Rationality, and the First Person. Clarendon Press, Oxford (2007)

Gutzmann, D.: Use-Conditional Meaning: Studies in Multidimensional Semantics. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2015)

Heine, B., Miyashita, H.: Accounting for a functional category: German drohen ‘to threaten’. Lang. Sci. 30(1), 53–101 (2008)

Hintikka, J.: Knowledge and Belief. Cornell University Press, Ithaca (1962)

Jędrzejowski, L.: On the grammaticalization of temporal-aspectual heads: the case of German versprechen ‘promise’. In: Truswell, R., Mathieu, É. (eds.) Micro-change and Macro-change in Diachronic Syntax, pp. 307–336. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2017)

MacFarlane, J.: Assessment Sensitivity. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

Mandelkern, M.: Bounded modality. Philos. Rev. 128(1), 1–61 (2019)

Matthewson, L., Todorović, N., Schwan, M.D.: Future time reference and view point aspect: evidence from Gitksan. Glossa: J. Gener. Linguist. 7(1), 1–37 (2022)

Matthewson, L., Truckenbrodt, H.: Modal flavour/modal force interactions in German: soll, sollte, muss and müsste. Linguist. Berichte 255, 3–48 (2018)

McCready, E.: Varieties of conventional implicatures. Semant. Pragmat. 3, 1–57 (2010)

McCready, E., Ogata, N.: Evidentiality, modality and probability. Linguist. Philos. 30(2), 147–206 (2007)

Moens, M., Steedman, M.: Temporal ontology and temporal reference. Comput. Linguist. 14(2), 15–28 (1988)

Moore, G.E.: A reply to my critics. In: Schilpp, P.A. (ed.) The Philosophy of G. E. Moore, pp. 535–677. Open Court, La Salle (1942)

Murray, S.E.: The Semantics of Evidentials, Oxford Studies in Semantics and Pragmatics, vol. 9. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2017)

Partee, B.H.: Some structural analogies between tenses and pronouns in English. J. Philos. 70(18), 601–609 (1973)

Plungian, V.A.: The place of evidentiality within the universal grammatical space. J. Pragmat. 33(3), 349–357 (2001)

Potts, C.: The Logic of Conventional Implicatures. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2005)

Reis, M.: Zur Grammatik der sog. Halbmodale drohen/versprechen + Infinitiv. In: d’Avis, F. (ed.) Deutsche Syntax: Empirie und Theorie, pp. 125–145. Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Göteborg (2005)

Reis, M.: Modals, so-called semi-modals, and grammaticalization in German. Interdisc. J. Germanic Linguist. Semiotic Anal. 12, 1–57 (2007)

Rullmann, H., Matthewson, L.: Towards a theory of modal-temporal interaction. Language 94(2), 281–331 (2018)

Schlenker, P.: Local contexts. Semant. Pragmat. 2(3), 1–78 (2009)

Yalcin, S.: Epistemic modals. Mind 116(464), 983–1026 (2007)

Yalcin, S.: Nonfactualism about epistemic modality. In: Egan, A., Weatherson, B. (eds.) Epistemic Modality, pp. 144–178. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2011)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Okano, S. (2023). Detecting Modality and Evidentiality. In: Bekki, D., Mineshima, K., McCready, E. (eds) Logic and Engineering of Natural Language Semantics. LENLS 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 14213. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43977-3_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43977-3_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-43976-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-43977-3

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)