Abstract

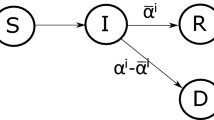

We analyze a mean field game where the players dynamics follow the SIR model. The players are the members of the population and the strategy consists in choosing the probability of being exposed to the infection, i.e., its confinement level. The goal of each player is to minimize the sum of the confinement cost, which is linear and decreasing on its strategy, and a cost of infection per unit time. We formulate this problem as a mean field game and we investigate the structure of a mean field equilibrium. We study the behavior of agents during the end of the epidemic, where the proportion of infected population is decreasing. Our main results show that: (a) when the cost of infection is low, a mean field equilibrium consists of never getting confined, i.e., the probability of being exposed to the infection is always one and (b) when the cost of infection is large, a mean field equilibrium consists of being confined at the beginning and, after a given time, being exposed to the infection with probability one.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

PPAD stands for “polynomial parity arguments on directed graphs”. It is a complexity class that is a subclass of NP and is believed to be strictly greater than P.

References

Anderson, R.M., May, R.M.: Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control. Oxford University Press, Oxford (1992)

Cabannes, T., et al.: Solving n-player dynamic routing games with congestion: a mean field approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.11943 (2021)

Cho, S.: Mean-field game analysis of sir model with social distancing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.06758 (2020)

Daskalakis, C., Goldberg, P.W., Papadimitriou, C.H.: The complexity of computing a Nash equilibrium. SIAM J. Comput. 39(1), 195–259 (2009)

Diekmann, O., Andre, J., Heesterbeek, P.: Mathematical Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases: Model Building, Analysis and Interpretation, vol. 5. Wiley, Hoboken (2000)

Doncel, J., Gast, N., Gaujal, B.: Discrete mean field games: existence of equilibria and convergence. J. Dyn. Games 6(3), 1–19 (2019)

Doncel, J., Gast, N., Gaujal, B.: A mean field game analysis of sir dynamics with vaccination. Probab. Eng. Inf. Sci. 36(2), 482–499 (2022)

Elie, R., Mastrolia, T., Possamaï, D.: A tale of a principal and many, many agents. Math. Oper. Res. 44(2), 440–467 (2019)

Ghilli, D., Ricci, C., Zanco, G.: A mean field game model for Covid-19 with human capital accumulation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.04004 (2022)

Huang, K., Di, X., Du, Q., Chen, X.: A game-theoretic framework for autonomous vehicles velocity control: bridging microscopic differential games and macroscopic mean field games. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.06053 (2019)

Huang, M., Malhamé, R.P., Caines, P.E.: Large population stochastic dynamic games: closed-loop Mckean-Vlasov systems and the Nash certainty equivalence principle. Commun. Inf. Syst. 6(3), 221–252 (2006)

Hubert, E., Turinici, G.: Nash-MFG equilibrium in a sir model with time dependent newborn vaccination (2016)

Kermack, W.O., McKendrick, A.G.: A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character, 115(772), 700–721 (1927)

Kolokoltsov, V.N., Malafeyev, O.A.: Corruption and botnet defense: a mean field game approach. Int. J. Game Theory 47(3), 977–999 (2018)

Laguzet, L., Turinici, G.: Global optimal vaccination in the sir model: properties of the value function and application to cost-effectiveness analysis. Math. Biosci. 263, 180–197 (2015)

Lasry, J.-M., Lions, P.-L.: Jeux à champ moyen. i-le cas stationnaire. Comptes Rendus Mathématique 343(9), 619–625 (2006)

Lasry, J.-M., Lions. , P.-L.: à champ moyen. ii-horizon fini et contrôle optimal. Comptes Rendus Mathématique 343(10), 679–684 (2006)

Lasry, J.-M., Lions, P.-L.: Mean field games. Japan. J. Math. 2(1), 229–260 (2007)

Olmez, S.Y., et al.: How does a rational agent act in an epidemic? arXiv e-prints, pp. arXiv-2206 (2022)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Proof of Lemma 1

We first note that \( V_I^*(T-1)=c_I+(1-\rho )V_I^*(T)=c_I, \) which clearly verifies the desired condition.

We now assume that \(V_I^*(t+1)=c_I\sum _{i=0}^{T-2-t}(1-\rho )^i,\) for \(t<T-1\) and we verify the following:

And the desired result follows.

Proof of Lemma 2

Let us first observe that the desired result holds for \(t=T\) since \(V_S^*(T)=0 \) and \(V_I^*(T)=0\). We now note that, from Lemma 1, we have that \(V_I^*(T-1)=c_I\). Besides, using that when \(t=T-1\) the best response to \(\pi \) is always one, it follows that \(V_S^*(T-1)=c_L-1\). As a consequence, \(V_S^*(T-1)\ge V_I^*(T-1)\) when \(c_I\le c_L-1\), i.e., the desired result is also satisfied when \(t=T-1\). We now assume that \(V_S^*(t+1)\ge V_I^*(t+1)\) for \(t<T-1\) and we verify that \(V_S^*(t)\ge V_I^*(t)\) when \(c_I\le c_L-1\).

where the last equality holds since \(V_I^*(t+1)-V_S^*(t+1)\le 0\) and, therefore, the value that minimizes \(c_L-\pi ^0(t)+(1-\gamma m_I(t)\pi ^0(t))V_S^*(t+1)+\gamma m_I(t)\pi ^0(t)V_I^*(t+1)\) is \(\pi ^0(t)=1\). Since \(V_I^*(t)=c_I+(1-\rho )V_I^*(t+1)<c_I+V_I^*(t+1)\), it follows that

which is clearly non-positive because \(c_I\le c_L-1\) and \(\gamma m_I(t)<1\) and since we assumed that \(V_S^*(t+1)\ge V_I^*(t+1)\). And the desired result follows.

Proof of Lemma 3

Since the best response at time t is one,

Besides,

As a result,

And the desired result follows.

Proof of Proposition 2

We know that the best response to \(\pi \) is one when \(t=T-1\) because the costs at time T are zero. Therefore, we only need to show that the best response to any \(\pi \) is one for all \(t<T-1\).

We assume that the best response to any \(\pi \) is one at time \(t+1\). Therefore, from Lemma 3, it follows that

As a result,

From Assumption 1, it follows that \(m_I(t)<m_I(0)\) and therefore, the rhs of the above expression is upper bounded by

because \(c_I\left( 1+\frac{1-(1-\rho )^{T-1}}{\rho }\right) -c_L+1 >0\) since \(c_I>c_L-1\) and \(\rho >0\). Since we have that

from the above reasoning, it follows that

which, according to (COND-BR=1), it implies that the best response to any \(\pi \) at time t is one. And the desired result follows.

Proof of Proposition 4

Let us recall that the best response to any \(\pi \) at time \(T-1\) is one. We aim to show that, when (COND1-JUMP) holds, the best response to \(\pi \) does not have more than one jump. For a fixed strategy \(\pi \), let \(t_0\) be the first time (starting from T) such that the best response to \(\pi \) is zero. The desired result follows if we show that for all \(t\le t_0\) the best response to \(\pi \) is zero. Using an induction argument, we assume that, there exists a \(\bar{t}\le t_0\) such that the best response to \(\pi \) at time \(\bar{t} \) is zero, which according to (COND-BR=0) is achieved when

and we aim to show that

i.e., that the best response to \(\pi \) at time \(\bar{t}-1\) is zero as well. Since the best response to \(\pi \) at time \( \bar{t}\) is zero, it follows that

and we also have that \(V_I^*(\bar{t})=c_I(1-\rho )^{T-\bar{t} -1 }+V_I^*(\bar{t}+1)\). As a result,

From (5), we obtain that \(V_I^*(\bar{t}+1)-V_S^*(\bar{t}+1)>\frac{1}{\gamma m_I(\bar{t}) }\), therefore

From (COND1-JUMP), we derive that \(c_I(1-\rho )^{T-\bar{t} -1 }-c_L>0\), which means that the rhs of the above expression is lower bounded by

We multiply both sides by \(\gamma m_I(\bar{t}-1)\):

We now notice that \(\frac{m_I(\bar{t}-1)}{m_I( \bar{t})}>1\) due to Assumption 1 and, therefore, (6) holds which implies that the desired result follows.

Proof of Lemma 4

1.1 \(\widetilde{m}_I(t)\ge m_I(t)\)

We first show that \(\widetilde{m}_I(t)\ge m_I(t)\) for \(t\ge 0.\) We note that, at time zero, both values coincide, i.e., \(\widetilde{m}_I(0)= m_I(0)\). We now assume that for \(t \ge 0\), \(\widetilde{m}_I(t)\ge m_I(t)\), and we aim to show that \(\widetilde{m}_I(t+1)\ge m_I(t+1)\). Using (1) and also that \(\bar{\pi }(t)\) is formed by all zeros,

whereas for \(\widetilde{\pi }\) we have

And the desired result follows.

1.2 \(V_I^*(t)\ge V_S^*(t)\)

We now focus on the proof of \(V_I^*(t)\ge V_S^*(t)\) for all \(t>t_0\). We first note that \(V_I^*(T)=V_S^*(T)=0\) and, therefore, the desired result follows at time T. We now assume that \(V_I^*(t+1)\ge V_S^*(t+1)\) for \(t+1>t_0\) and we aim to show that \(V_I^*(t)\ge V_S^*(t)\). Since the best response to \(\bar{\pi }\) at time t is one, we have that

and taking into account that \(V_I^*(t)=c_I(1-\rho )^{T-1-t}+V_I^*(t+1)\), we have that

which holds since \(V_I^*(t+1)\ge V_S^*(t+1)\) and \(c_I \ge \frac{c_L}{(1-\rho )^{T-1}}>\frac{c_L}{(1-\rho )^{T-t-1}}\). And the desired result follows.

1.3 \(\widetilde{V}_S^*(t)\ge V_S^*(t)\)

Finally, we show that \(\widetilde{V}_S^*(t)\ge V_S^*(t)\) for all \(t>t_0.\) We know that \(\widetilde{V}_S^*(T)= V_S^*(T)=0\) since the cost at the end is zero. Therefore, we assume that \(\widetilde{V}_S^*(t+1)\ge V_S^*(t+1)\) for \(t>t_0\) and we aim to show that \(\widetilde{V}_S^*(t)\ge V_S^*(t)\).

We know that the best response to \(\bar{\pi }\) for \(t>t_0\) is one. Therefore, \(V_S^*(t)=c_L-1+V_S^*(t+1)+\gamma m_I(t)(V_I^*(t+1)-V_S^*(t+1))\). For \(\widetilde{V}_S^*(t)\), we denote by a the best response to \(\widetilde{\pi }\) at time t. Thus,

Using that \(\widetilde{V}_S^*(t+1)\ge V_S^*(t+1)\) and because \(1-\gamma \widetilde{m}_I(t)a\) is positive, we get

Therefore, \(\widetilde{V}_S^*(t)\ge V_S^*(t)\) is true when

Simplifying

Using that \(\widetilde{m}_I(t)\ge m_I(t)\) and since \(V_I^*(t+1)-V_ S^*(t+1)\) is non-negative, the rhs of the above expression is smaller or equal than \(\gamma (1-a)m_I(t)(V_I^*(t+1)-V_ S^*(t+1))\). Therefore, a sufficient condition for the desired result to hold is

We now differentiate two cases: (a) when \(a=1\), we have zero in both sides of the expression and therefore, the condition is satisfied; (b) when \(a\ne 1\), we divide by \(1-a\) both sides of the expression and we get

which is also satisfied from (COND-BR=1) because the best response to \(\bar{\pi }\) at time t is one.

Proof of Lemma 6

We aim to show that

for \(t>t_0\). From Lemma 5 we know that the best response to \(\widetilde{\pi }\) is one for \(t>t_0\), because (COND1-JUMP) is satisfied, and therefore,

From Lemma 1, we have that

Therefore,

Hence, using the above expression, we get that

We now note that when \(c_I\ge \frac{c_L}{(1-\rho )^{T-1}},\) we get \(c_I(1-\rho )^{T-t-1}>c_L\), and as the best response to \(\widetilde{\pi }\) is one we have (COND-BR=1). Therefore,

and the desired result follows.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Sagastabeitia, G., Doncel, J., Gast, N. (2023). To Confine or Not to Confine: A Mean Field Game Analysis of the End of an Epidemic. In: Forshaw, M., Gilly, K., Knottenbelt, W., Thomas, N. (eds) Practical Applications of Stochastic Modelling. PASM 2022. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1786. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-44053-3_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-44053-3_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-44052-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-44053-3

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)