Abstract

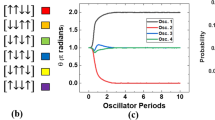

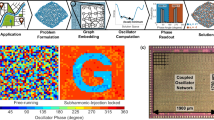

Oscillator Ising Machines (OIMs) are networks of coupled nonlinear oscillators that solve the NP-hard Ising problem heuristically. Conventionally, the oscillators in an OIM are coupled using resistors. However, the phase-domain properties of such couplers are unsatisfactory; resistively-coupled OIMs do not realize the optimization performance predicted by simulations of idealized OIMs. This has been a major hurdle impeding the development of high quality analog OIMs on integrated circuits. In this paper, we present a novel coupling scheme, the sampling coupler, that addresses this issue theoretically and practically. Essentially, a sampling coupler injects a current that depends on the phase difference between interacting oscillators. We prove analytically that using sampling couplers leads to idealized OIMs, abstracting away the waveforms and innate phase sensitivities of the oscillators. We evaluate sampling-coupler OIMs (using simulation) on a practically-important digital wireless communication problem and show that the performance is near-optimal. Sampling couplers therefore open up a way to implement practically feasible, high-performance analog OIMs using virtually any oscillator.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

More precisely: independent of the actual hardware implementation (which can use, e.g., active elements instead of resistors), an oscillator couples to another by injecting a signal proportional to its voltage waveform.

- 2.

PPV stands for Perturbation Projection Vector; it is a periodic function that completely captures the dynamics of an oscillator’s phase response to external inputs, such as those from other oscillators via coupling [7].

- 3.

MU-MIMO stands for Multi-User Multi-Input Multi-Output.

- 4.

SHIL is an abbreviation of Sub-Harmonic Injection Locking; it is a phenomenon observed in nonlinear oscillators. In SHIL, the oscillator gets forced to oscillate in either one of two stable phases separated by \(\pi \) radians when it is perturbed by an external signal of a frequency that is twice the natural frequency of the oscillator [2].

- 5.

This is characteristic of all Ising machines, as well as of optimization algorithms like simulated annealing.

- 6.

- 7.

Simulating a coupled system of “Un-Adlerized” PPV equations for the OIM network, as we do to generate some of our results in this paper, provides more accurate results than (6), though it requires somewhat greater computational effort.

- 8.

For simplicity and brevity, we focus on \(\textrm{F}_{\textrm{c}}(\cdot )\) in the following; the reasoning for \(\textrm{F}_{\textrm{s}}(\cdot )\) is very similar.

- 9.

The ‘d’ stands for ‘desired’.

- 10.

It is easy in practice to turn most waveforms into square ones using a simple thresholding circuit.

- 11.

The simulations used the Forward Euler technique for numerical solution of ordinary differential equations, as noted in [26].

- 12.

Doing so greatly increases data rate and reliability compared to single-antenna systems.

- 13.

Note, however, that resistive coupling in OIMs with specially designed oscillators can produce good results for some problems, such as MAX-CUT [21].

- 14.

- 15.

The flip-flop can have a nonzero clock-to-Q delay, but we assume it is designed to avoid metastability, i.e., such delays will not be indefinitely long.

- 16.

If \(K_c\) is negative, then the signs of the coupling coefficients get reversed. The improbable case of \(K_c\) being zero or very small can be remedied by shifting \(w(\cdot )\) by some delay.

References

Marandi, A., Wang, Z., Takata, K., Byer, R.L., Yamamoto, Y.: Network of time-multiplexed optical parametric oscillators as a coherent Ising machine. Nat. Photonics 8(12), 937–942 (2014)

Neogy, A., Roychowdhury, J.: Analysis and design of sub-harmonically injection locked oscillators. In: Proceedings of IEEE DATE, March 2012

Adler, R.: A study of locking phenomena in oscillators. Proc. I.R.E. Waves Elect. 34, 351–357 (1946)

Adler, R.: A study of locking phenomena in oscillators. Proc. IEEE 61, 1380–1385 (1973), reprinted from [3]

Afoakwa, R., Zhang, Y., Vengalam, U.K.R., Ignjatovic, Z., Huang, M.: BRIM: bistable resistively-coupled Ising machine. In: 2021 IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA), pp. 749–760. IEEE (2021)

Damen, M.O., El Gamal, H., Caire, G.: On maximum-likelihood detection and the search for the closest lattice point. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 49(10), 2389–2402 (2003)

Demir, A., Mehrotra, A., Roychowdhury, J.: Phase noise in oscillators: a unifying theory and numerical methods for characterization. IEEE Trans. Ckts. Syst. I. 47(5), 655–674 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1109/81.847872

Demir, A., Roychowdhury, J.: A reliable and efficient procedure for oscillator PPV computation, with phase noise macromodelling applications. IEEE Trans. CAD 22, 188–197 (2003)

Fincke, U., Pohst, M.: Improved methods for calculating vectors of short length in a lattice, including a complexity analysis. Math. Comput. 44(170), 463–471 (1985). https://doi.org/10.2307/2007966

Goutay, M., Aoudia, F.A., Hoydis, J.: Deep Hypernetwork-based MIMO Detection. In: 21st International Workshop on Signal Processing Advances in Wireless Communications (SPAWC), pp. 1–5. IEEE (2020)

Hamerly, R., et al.: Experimental investigation of performance differences between coherent Ising machines and a quantum Annealer. Sci. Adv. 5(5), eaau0823 (2019)

Hassibi, B., Vikalo, H.: On the expected complexity of sphere decoding. In: Conference Record of Thirty-Fifth Asilomar Conf. on Signals, Systems and Computers, vol. 2, pp. 1051–1055. IEEE (2001)

Acebrón, J.A., Bonilla, L.L., Vicente, C.J.P., Ritort, F., Spigler, R.: The Kuramoto model: a simple paradigm for synchronization phenomena. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77(1), 137 (2005)

Kim, M., Venturelli, D., Jamieson, K.: Leveraging quantum annealing for large MIMO processing in centralized radio access networks. In: Proceedings of the ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication, pp. 241–255. ACM (2019)

Kuramoto, Y.: Self-entrainment of a population of coupled non-linear oscillators. In: Araki, H. (eds.) International Symposium on Mathematical Problems in Theoretical Physics. LNP, vol. 39, pp. 420–422. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg (1975). https://doi.org/10.1007/BFb0013365

Lucas, A.: Ising formulations of many NP problems. Front. Phys. 2, 5 (2014)

Lyapunov, A.M.: The general problem of the stability of motion. Int. J. Control 55(3), 531–534 (1992)

Pohst, M.: On the computation of lattice vectors of minimal length, successive minima and reduced bases with applications. SIGSAM Bull. 15(1), 37–44 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1145/1089242.1089247

Proakis, J.G., Salehi, M.: Digital Communications, 5th edn. McGraw Hill, Boston (2008)

Roychowdhury, J., Wabnig, J., Srinath, K.P.: Performance of Oscillator Ising Machines on Realistic MU-MIMO Decoding Problems. Research Square preprint (Version 1), September 2021

Sreedhara, S., Roychowdhury, J.: Oscillatory Neural Networks—from Devices to Computing Architectures, chap. Oscillator Ising Machines. Springer (2024). (to appear)

Sreedhara, S., Roychowdhury, J., Wabnig, J., Srinath, K.P.: Digital emulation of oscillator Ising machines. In: Proceedings of IEEE DATE, pp. 1–2 (2023)

Sreedhara, S., Roychowdhury, J., Wabnig, J., Srinath, P.K.: MU-MIMO Detection Using Oscillator Ising Machines. In: Proc. ICCAD. pp. 1–9 (2023)

Inagaki, T., et al.: A coherent Ising machine for 2000-node optimization problems. Science 354(6312), 603–606 (2016)

Wang, T., Roychowdhury, J.: OIM: Oscillator-based Ising Machines for Solving Combinatorial Optimisation Problems. arXiv:1903.07163 (2019)

Wang, T., Roychowdhury, J.: Oscillator-based Ising Machine. arXiv:1709.08102 (2017)

Wang, T., Roychowdhury, J.: OIM: oscillator-based Ising machines for solving combinatorial optimisation problems. In: McQuillan, I., Seki, S. (eds.) UCNC 2019. LNCS, vol. 11493, pp. 232–256. Springer, Cham (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19311-9_19

Wang, T., Wu, L., Nobel, P., Roychowdhury, J.: Solving combinatorial optimisation problems using oscillator based Ising machines. Nat. Comput. 20, 1–20 (2021)

Bian, Z., Chudak, F., Israel, R., Lackey, B., Macready, W.G., Roy, A.: Discrete optimization using quantum annealing on sparse Ising models. Front. Phys. 2, 56 (2014)

Acknowledgments

This work was enabled by support from the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the US National Science Foundation (NSF); additional support was provided by Berkeley’s Bakar Prize Program. The MU-MIMO benchmark set used in this paper was provided by Pavan K. Srinath and Joachim Wabnig of Nokia Bell Labs. We thank Thomas Hart and Charles Macedo for important inputs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

A Sampling-Coupler Based OIMs Achieve \(\mathrm {F_{c,d}}(\cdot )\)

A Sampling-Coupler Based OIMs Achieve \(\mathrm {F_{c,d}}(\cdot )\)

Here, we prove that the actual \(\textrm{F}_{\textrm{c}}(\cdot )\) of the sampling coupler is in fact equal to a scaled version of the ideal \(\mathrm {F_{c,d}}(\cdot )\). We start from the PPV equation ((7), repeated here):

Here, \(\varDelta \phi (t)\) is the phase change of the oscillator, \(\boldsymbol{v}^T(\cdot )\) is its vector of 1-periodic PPVs, and \(\boldsymbol{b}(t)\) is the vector of inputs applied to the oscillator.

Applying the above PPV model to the two oscillators coupled via sampling couplers, we get

where \(b_i(t)\) and \(b_j(t)\) represent the inputs into each oscillator from the other via the sampling couplers in Fig. 3. Note that vector PPVs and inputs (i.e., \(\boldsymbol{v}(\cdot )\) and \(\boldsymbol{b}(t)\) respectively) have been replaced by scalars; this is a simplification (for exposition) assuming a single scalar input, i.e., \(\boldsymbol{b}\) has only one nonzero component.Footnote 14

We now focus on \(OSC_i\) and derive its actual \(\textrm{F}_{\textrm{c}}(\cdot )\). The input \(b_{i}(t)\), represented in Fig. 3 by \(I_{src,i,j}\), has the form

where:

-

\(J_{i,j}\) is the Ising coupling coefficient (from (1)) between the \(i^\text {th}\) and the \(j^\text {th}\) oscillator.

-

\(\textrm{F}_{\textrm{c,d}}\left( \varDelta \phi _i(t)-\varDelta \phi _j(t)\right) \) is the value of the sample held by \(DFF_{i,j}\) in Fig. 3, as established in Sect. 3. Note that \(\varDelta \phi _i\) and \(\varDelta \phi _j\) in (11) now change with time as the system evolves. However, the flip-flops in Fig. 3 hold the value at the last sampling instant until the next sample; this is not captured by \(\textrm{F}_{\textrm{c,d}}\left( \varDelta \phi _i(t)-\varDelta \phi _j(t)\right) \).

-

The \(w(\cdot )\) term captures the sampling aspect of the flip-flop. Note that the flip-flop \(DFF_{i,j}\) samples at transitions of \(x_i(t)\), i.e., its sampling instant is timed using the phase \(f_0t + \varDelta \phi _i(t)\) of \(OSC_i\). Ideal sampling would be captured by a weighted delta function of this phase, i.e., \(C w(f_0t + \varDelta \phi _i(t) + \theta )\), where \(w(\cdot )\) is a unit impulse train with period 1, C is a weight, and \(\theta \) is a constant phase offset, useful for adjusting the sampling instant within each cycle and/or to model clock-to-Q delay in the flip-flop.Footnote 15 However, \(w(\cdot )\) can in fact be almost any 1-periodic function for the scheme to work, as we show below; incorporating C into, and using a \(\theta \)-shifted version of, a given \(w(\cdot )\) simplifies the expression to \(w(f_0t + \varDelta \phi _i(t))\).

Substituting \(b_{i}(t)\) in (10), we obtain

Now, we assume that the phases \(\varDelta \phi _i(t)\) and \(\varDelta \phi _j(t)\) vary ‘slowly’— this is a standard assumption for averaging or “Adlerization”; [2, 4]. With this assumption, the Adlerization of (12) is

where \(\phi \) represents the nominal oscillator phase, \(f_0t\). Simplifying the above leads to

where \(\psi \triangleq \varDelta \phi _i(t)+\phi \). For the last step, we used the fact that the integral remains the same over any interval of length 1 since both \(v(\cdot )\) and \(w(\cdot )\) are 1-periodic.

It is convenient, though not necessary,Footnote 16 to assume that

Using this definition of \(K_c\) in (14), we get

Comparing (16) to (6), we have shown that the actual \(\textrm{F}_{\textrm{c}}(\cdot )\) from using sampling couplers is indeed equal to a scaled version of \(\textrm{F}_{\textrm{c,d}}\left( \theta \right) \).

The above generalizes straightforwardly to the case of N coupled oscillators, resulting in

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Sreedhara, S., Roychowdhury, J. (2024). A Novel Oscillator Ising Machine Coupling Scheme for High-Quality Optimization. In: Cho, DJ., Kim, J. (eds) Unconventional Computation and Natural Computation. UCNC 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 14776. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-63742-1_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-63742-1_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-63741-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-63742-1

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)