Abstract

Social applications do not only acquire users’ personal information but potentially also collects the personal information of users’ social networks. Despite considerable discussion of privacy problems in prior work, questions remain as to how to design privacy-preserving social applications and how to evaluate its effect on privacy. Drawing on the justice framework, we identify two key aspects of social, namely information acquisition and exposure control and examine the effects on user evaluation of social applications. Furthermore, we investigate the impact of this evaluation on usage intention. In doing so, we provide new insight into embedding privacy in technology development.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Recently, in an attempt to expand the functionality of their social platforms, online social networks such as Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn, have begun opening their platforms to allow third party developers to create social applications to improve the experience of users online. Social applications are essentially software programs that are developed to enhance social interactivity on online social networks. These applications have fundamentally augmented the online social networks experience by creating a spectrum of new, functional and entertaining software that have become a new paradigm of social interaction [1]. There are over 200 million users currently using social applications, with that number expected to double within the next 5 years [2]. The surge in the popularity of social applications has also become a significant revenue stream for these online social networks with platforms such as Facebook Platform, yielding revenues of 1.96 Billion dollars.

Despite the increasing popularity of social applications, the concern of users over privacy appears to be the biggest obstacle when individuals are deciding to use these applications [3]. As identified by prior privacy research, these may include but are not limited to, accidental information disclosure, damaged reputation and image, and identity thieves [e.g., 4, 5]. The advancement of technologies embedded and used in the social environment can further raise users’ perception of privacy risk because these applications do not only threaten personal privacy but also invade the privacy of users’ online social network friends. For example, Angwin and Singer-Vine [6] analyzed 100 of the most-used applications on Facebook and found that users did not only expose their own profile information, such as name, profile photo, and gender, but also reveal their friends’ profile information (i.e., friends’ profile photos, names, and genders). Overall, this extended scope of profile information collection has stirred concerns among users.

The objective of this research is to enrich understanding of information privacy in the context of social application usage. Specifically, we aim to enhance the literature by developing and testing a model that explains social application usage. Drawing on the justice framework, we examine how extended information collection (such as the collection of network information) and control over profile exposure (such as the ability to deny disclosure) can influence user evaluation, which in turn, influence their usage intention. By doing so, we seek to provide new insight into embedding privacy proactively into the core of social application designs.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section reviews previous literature and discusses the theoretical foundation for this study. The research model and hypotheses are then proposed, followed by the introduction of research methodology and the report of the data analysis results. This paper concludes with the discussion of theoretical and practical contributions, limitations, and avenues for future research.

2 Literature Review

2.1 The Justice Framework

The justice framework has been vastly accepted as an important framework in understanding privacy issues [7, 8]. Indeed, ample scholarly efforts have been devoted to theoretical development for analyzing privacy through a justice theoretical lens. For example, Son and Kim [8] examined internet users’ information privacy protective responses and found that individuals’ perceptions of justice powerfully drove their privacy-related behavior. Overall, a general conclusion from this stream of research is that individuals’ justice perceptions of a firm’s information practices can have a major positive effect on their privacy decision making [9].

In the context of information privacy, two key types of justice are found to be imperatively important, namely distributive justice and procedural justice [10]. Distributive justice refers to the evaluation of fairness of economic and socio-emotional outcomes [11]. Distributive justice is promoted when outcomes are coherent with implicit norms for distribution. In particular, past research found that perceptions of outcome fairness were largely developed based on the equity principle [12, 13]. The equity principle posits that outcomes should be distributed in accordance to the cost incurred on individuals. This concept is consistent with the privacy calculus or a psychological tradeoff that is widely established in privacy research, which suggests that individuals evaluate the exchange outcome when their personal information is concerned.

Procedural justice typically manifests in the structural aspects of procedures, such as process control and fair allocative procedures [14]. Past research suggests that procedural justice can be enhanced when the decision processes enable the correction of wrong decisions, represents the needs and values of all parties in the exchange, and meets the ethical and moral values of the social system. More importantly, recent studies highlight the importance of individuals’ ability to voice their opinions through the decision process in ensuring procedural justice. Collectively, these studies demonstrate the viability of procedural justice in explaining behavioral outcomes across a broad range of contexts.

2.2 Challenges to Distributive Justice – Information Acquisition

Consistent with the justice framework, in the context of social application usage, distributive justice can be challenged when individuals’ profile information is acquired by social applications. This study focuses on local and global profile acquisition, which is particularly prevalent when individuals evaluate social applications. Local information acquisition is about the collection of users’ own profile information. When local information is acquired, a user’s personal information, which resides on his or her personal profile, is revealed to the social applications. Local information acquisition often involves the collection of an extensive range of profile information, such as profile names, email addresses, genders, and birthdays [15].

Global information acquisition does not only involve the collection of a user’s own profile information but also entails information collection that involves the profiles of his or her online social networks [15]. When global information is acquired, in addition to the user’s profile information, it collects friends’ profile information, such as his or her list of friends, their profile names, email addresses, genders, and birthdays. Since users are entrusted with their friends’ profile information, users often assume to have a stake of ownership over such information and expect to exercise some control over the exposure of the shared information.

2.3 Challenges to Procedural Justice – Exposure Control

Exposure control refers to the design feature that enables users to regulate who can access and use their personal information when they use social applications. In the context of information privacy, fair information practice (FIP) principles serve as global normative standards that reflect procedural justice, which include the stipulations that users should be given control with regard to the use of their information [16]. Indeed, according to contemporary choice theory, in privacy situations, users evaluate attributes of choice alternatives, which may comprise both economic and psychological factors, to make privacy decisions [17].

Consistent with contemporary choice theory, exposure control can be challenged when users’ profile information is compulsorily acquired by social applications. This study focuses on optional exposure and compulsory exposure of users’ profile information. When optional exposure is available, a user might choose the specific profile information to reveal to the application provider. Past privacy research indicates that users’ privacy concerns can be addressed by providing users with more control over their information [e.g., 9, 18]. By retaining control over information provision, users could protect their personal information and hence become less concerned about their privacy.

Compulsory exposure makes revelation of profile information mandatory for application usage. With compulsory exposure, users do not only lose control over their own profile information, but often at times lose control over their friends’ profile information as well. This lack of control over information engenders mistrust in the technology and induces the perceptions of risks of data extraction.

2.4 Privacy Calculus

Whereas the justice framework sheds light on the two privacy aspects of the social application, past work on privacy calculus helps understand individuals’ cognitive evaluation processes. In particular, previous research suggests that when individuals’ personal information is concerned, they undergo a privacy calculus to evaluate the cost and benefit of the exchange [17]. Prior IS research on privacy calculus have examined this concept in a variety of contexts, such as online commerce, location-aware marketing, and online social interactions [e.g., 19]. Yet little is known about the role of privacy calculus in social application usage. In this study, individuals’ cost and benefit evaluations are represented by perceived privacy risk and perceived application value. Perceived privacy risk refers to the degree to which an individual believes that a high potential for loss is associated with social app usage [20]. Prior privacy literature has identified aspects of privacy situations that induce privacy risk, including information collection and information control. Individuals often estimate privacy risk by considering the types of information collection as well as their ability to control information after revelation.

Usage of technology is typically driven by the value the technology can provide to users [21]. Accordingly, we examine perceived application value, which refers to the extent to which the social application fulfills user’s personal needs [22], as a major benefit that individuals derive from using social applications. Research on value evaluation theorizes that individuals’ perception of application value is highly dependent on the types of information acquisition, which allows users to evaluate the relevance and importance of information collection [23, 24]. Usage of social applications typically involves information collection, which is commonly considered relevant when individuals’ personal information is acquired by an application.

Past studies examining value evaluation also suggests that subsequent control over revealed information is an important consideration in assessing application value [20]. The value of technologies related to personal information disclosure has often been discounted when individuals are denied control over their information [25]. Without proper control, the information collected for one purpose can be used for another, secondary purpose. Control is especially important in social application usage context because users take higher risks in the submission of profile information. Several studies have suggested that in reality, individuals want to have the ability to control information exposure.

3 Research Model and Hypotheses Development

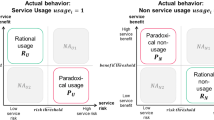

We present our research model in Fig. 1 below.

3.1 Information Acquisition and Privacy Calculus

Usage of social applications may involve a local scope of information acquisition or a global scope of information acquisition. When a local scope of information acquisition is performed, individual users’ profile information is acquired by the social application. As a result, the decision to use the application predominately challenges users’ personal privacy. In contrast, a global scope of information acquisition extends the extent of information collection beyond users’ profile information by acquiring the profile information of their online social network friends. Consequently, a global information acquisition scope does not only challenge individual personal privacy but also confronts the collective privacy [26].

Previous research has shown that the relevance of information collection influences users’ evaluation of application value [23, 24]. In particular, when the specific information collected is vital in enriching technology usage experience, users would believe the information collection is relevant and hence enhance their perception of application value [27]. However, when the information collected is deemed unnecessary in enabling usage experience, users would deem the information collection inappropriate and hence reduce their application value perception. Therefore, compared to a local scope of information acquisition, a global scope of information acquisition would escalate threats to the privacy of individuals’ entire online social network and reduce the value of using the application. Thus, we posit:

-

H1a: Compared to a local scope of information acquisition, a global scope of information acquisition will increase perceived privacy risk.

-

H1b: Compared to a local scope of information acquisition, a global scope of information acquisition will reduce perceived application value.

3.2 Exposure Control and Privacy Calculus

Past IS research has identified exposure control as a key privacy consideration in individuals’ evaluation of technology. For example, Son and Kim [8] revealed that online consumers typically reduced disclosure of personal information to protect privacy. Likewise, Hui et al. [25] reported that individuals did not only exercise exposure control by limiting disclosure but also reveal falsified information. Similarly, in social application usage, when individuals are given the options to selectively expose profile information, they might be less concerned about privacy invasions and become more appreciative to the value derived from using the application. In contrast, when they are not given such options, the exposure becomes compulsory and hence they could become more apprehensive about using the application. Therefore, we hypothesize:

-

H2a: Compared to selective profile exposure, compulsory profile exposure will increase perceived privacy risk.

-

H2b: Compared to selective profile exposure, compulsory profile exposure will reduce perceived application value.

3.3 Interaction Between Exposure Control and Information Acquisition

Referent cognitions theory (RCT) offers an explanation for the joint effect of information acquisition and exposure control on perceived privacy risk and perceived application value [28]. Specifically, this theory states that individuals tend to evaluate outcomes (i.e., information acquisition) based on whether fair procedures are followed (i.e., exposure control). When users have a high degree of control over their information, they would be less sensitive to information acquisition in using social applications. However, if they perceive a lack of control over their information, they are more likely to focus on attaining an equitable outcome. Thus, according to RCT, the question of whether exposure control was faithfully facilitated moderates the way users cognitively evaluate information acquisition.

In the case of selective profile exposure, users are allowed control over subsequent use of their profile information, thereby reducing their sensitivity toward information acquisition. However, in the case of compulsory profile exposure, equitable outcome for using the application cannot be guaranteed; hence, users’ sensitivity toward information acquisition is likely heightened. Taken together, in the context of social application usage, customers who are satisfied with exposure control tend to perceive the application to be less privacy threatening and more valuable; therefore, exposure control could complement information acquisition in affecting perceived privacy risk and perceived application value. Thus,

-

H3a: The effect of information acquisition on perceived privacy risk is weaker in the selective profile exposure condition than in the compulsory profile exposure condition.

-

H3b: The effect of information acquisition on perceived application value is stronger in the selective profile exposure condition than in the compulsory profile exposure condition.

3.4 Privacy Calculus and Usage Intention

Usage of social applications not only exposes individuals’ profile information to the provider but also makes them vulnerable to further privacy invasions. Past studies suggests that individuals’ perception of privacy invasion reduces usage intention in the online environment. For instance, Youn [29] examined online privacy-protective behavior and revealed that Internet users coped with privacy invasions by limiting participation in online transactions. Accordingly, we propose that usage is essential in realizing the value provided by the social application. For example, Grosser et al. [30] revealed that users who found social application valuable would be motivated to use the application. Specifically, usage was found to be determined by value, such as social connectivity and image gain. Usage can also be understood as a manifestation of commitment in online exchange, in that individuals acknowledge the value provided by the application. Therefore, individuals who perceive high application value will engage in usage behavior. This leads us to posit:

-

H4a: Higher perceived privacy risk will reduce usage intention.

-

H4b: Higher perceived application value will increase usage intention.

4 Research Methodology

4.1 Experimental Design

A laboratory experiment with 2 (Information Acquisition: Local Scope vs. Global Scope) × 2 (Exposure Control: Selective Profile Exposure vs. Compulsory Profile Exposure) factorial design was conducted to test the proposed hypotheses. Information acquisition was manipulated by the type of profile information collected by the application. Exposure control was facilitated by manipulating the availability of selective revelation.

4.2 Sample and Experimental Procedures

Subjects in this experiment were students at a large public university. Prior to the experiment, subjects were asked to provide information about demographics, Internet experience, Facebook experience, Facebook application experience, and dispositional privacy concerns.

5 Data Analysis

5.1 Subject Demographics and Background Analysis

Among the 130 subjects participating in the study, 62 were females. The age of the subjects ranged from 18 to 24, with average Internet experience an average Facebook experience being 8.2 years and 3.3 years, respectively. The average Facebook application experience was 2.41 years. In average, a subject spent 25.23 min to complete the entire experiment.

5.2 Measurements

The manipulation checks were performed. Results suggest that the manipulation for information acquisition and exposure control were successful.

Four items measuring perceived privacy risk were adapted from Folger and Konovsky [28] (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83) (see Table 1). Four items measuring perceived application value were adapted from Folger and Konovsky [28] (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89). Four items measuring usage intention were developed based on Mathieson [31] (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88). Exploratory factor analysis shows that, in general, items load well on their intended factors and lightly on the other factor, thus indicating adequate construct validity.

ANOVA with perceived privacy risk as dependent variable reveals the significant effects of information acquisition (F (1, 126) = 55.89, p < 0.01) and exposure control (F (1, 126) = 34.50, p < 0.01). Therefore, H1a and H2a are supported. The significant interaction effect (F (1, 126) = 26.18, p < 0.01) suggests that the effect of information acquisition on perceived privacy risk is moderated by exposure control. Simple main effect analysis reveals that (1) a global scope of information acquisition is associated with significantly higher perceived privacy risk than a local scope of information acquisition under the compulsory profile exposure condition (F (1, 66) = 67.23, p < 0.01), and (2) a global scope of information acquisition and a local scope of information acquisition are not different from each other in affecting perceived privacy risk under the selective profile exposure condition (F (1, 60) = 1.68, p = 0.20). Therefore, H3a is supported.

5.3 Results on Perceived Application Value

ANOVA with perceived application value as dependent variable reveals the significant effects of information acquisition (F (1, 126) = 12.56, p < 0.05) and exposure control (F (1, 126) = 85.48, p < 0.01). Therefore, H1b and H2b are supported. The significant interaction effect (F (1, 126) = 22.24, p < 0.01) suggests that the effect of information acquisition on perceived application value is moderated by exposure control. Simple main effect analysis reveals that (1) a global scope of information acquisition is associated with significantly lower perceived application value than a local scope of information acquisition under the selective profile exposure condition (F (1, 60) = 32.04, p < 0.01), and (2) a global scope of information acquisition and a local scope of information acquisition are not different from each other in affecting perceived application value under the compulsory profile exposure condition (F (1, 66) = 0.73, p = 0.57). Therefore, H3b is supported.

5.4 Results on Willingness to Profile Information Provision

PLS was used to test the structural model proposed on the right-hand side of Fig. 1. Results indicate that perceived privacy risk has a significant and negative effect on usage intention (p < .05). Thus, H3a is supported. In line with our expectation, perceived application value also positively affects usage intention (p < .05), thereby supporting H3b.

6 Discussion of Results

The results are in support of our hypotheses. We seek to provide a more holistic understanding of individuals’ usage of social applications by examining their privacy tradeoff when evaluating social applications. Whereas the cost in the tradeoff is subsumed in privacy risk, the benefit is embodied in application value. We establish that social application usage intention is negatively driven by privacy risk and positively motivated by application value. We also hope to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of privacy tradeoff in this context of social application usage by examining two antecedents: information acquisition and exposure control, which are derived based on the justice framework. Our findings show that these two antecedents powerfully predict both privacy risk and application value.

7 Contributions

We enrich information privacy studies on several grounds. First, we contribute to the IS literature by identifying antecedents of privacy tradeoff in the context of social application usage. While past studies have identified a myriad of factors pertinent to privacy issues, rarely have researchers put forth a coherent framework of antecedents. Drawing on the justice framework, we offer two antecedents, namely information acquisition and exposure control. Specifically, information acquisition accounts for the important role of distributive justice in privacy issues. The procedural aspect of justice is reflected by exposure control in social application usage. Overall, the justice framework offers a coherent perspective for future privacy research.

Furthermore, this study examines the interactions between information acquisition and exposure control that are unique to our context of social application usage. As hypothesized, exposure control somewhat complements information acquisition. Users with the ability to control the extent of profile information exposure tend to perceive information acquisition more acceptable than those without the ability to regulate exposure. To this end, our study offers a concrete account of how information acquisition and exposure control jointly shape users’ evaluations of social applications.

This study also offers several important practical contributions. We recommend that social application designers enhance existing technical features to effectively mitigate the impact of exposure control. This study reveals that privacy risk powerfully inhibits usage intention. To this end, we advocate that social application designers should allow individuals to exercise some control over the types of information exposure in using social applications.

Recall that, in our study, exposure control moderates the effects of information acquisition on privacy risk and application value. The results show that information acquisition is a critical attribute of social app evaluation. To help manage the impact of information acquisition, social application providers should exercise prudence in collecting profile information which is relevant to ensuring usage experience.

8 Limitations and Future Directions

We acknowledge some limitations in this study. First, our findings may also be limited by using an application evaluation scenario. While the mock-up application presented in the scenario resembled those of a real social application, the application may not completely reflect the actual environment. However, in the actual social networking environment (i.e., Facebook App Center), it would be impossible to manipulate the experimental conditions (i.e., controlling the number of friends using the application). Therefore, despite the limitation, the employment of scenarios is necessary. We encourage researchers to verify the impact of information acquisition and exposure control on social application in a more natural setting.

Furthermore, it could be possible that our findings are specific to the student samples and not necessarily generalized to other populations. For instance, our respondents might feel that they had little to “lose” economically or socially in terms of their profile information and displayed more willingness to use social applications. Despite this concern, university students are reported to represent a huge portion of the actual population engaging actively in social application usage. More importantly, university students are found to be vulnerable to privacy loss and become targets for physical and psychological threats.

This study opens up a number of exciting directions worthy of further pursuit. For example, this study examines individuals’ initial evaluation and usage of application apps. It is likely that individuals may behave differently if they have actual usage experience. We believe our theoretical perspective can be instrumental to these potential future studies.

Additionally, this study has focused on willingness usage intention. In a real setting, users might engage in other behaviors. For example, users might complain to friends about the usage of the application in physical interactions. Likewise, users might resign from using online social networks entirely. Hence, future research could investigate how users react to information collection by social applications in the offline environment.

References

Besmer, A., et al.: Social applications: exploring a more secure framework. In: Proceedings of the 5th Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security. ACM (2009)

Markets, R.A.: Global Online Gaming Market 2014. Research and Markets (2014)

Smock, A.D., et al.: Facebook as a toolkit: a users and gratification approach to unbundling feature use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 27(6), 2322–2329 (2011)

Boyd, D.M., Ellison, N.B.: Social network sites: definition, history, and scholarship. J. Comput. Mediated Commun. 13(1), 210–230 (2007)

Debatin, B., et al.: Facebook and online privacy: attitudes, behaviors, and unintended consequences. J. Comput. Mediated Commun. 15(1), 83–108 (2009)

Angwin, J., Singer-Vine, J.: Selling you on facebook (2012). http://online.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303302504577327744009046230

Culnan, M.J., Bies, R.J.: Consumer privacy: balancing economic and justice considerations. J. Soc. Issues 59(2), 323–342 (2003)

Son, J.-Y., Kim, S.S.: Internet users’ information privacy-protective responses: a taxonomy and a nomological model. MIS Q. 32(3), 503–529 (2008)

Culnan, M.J., Armstrong, P.K.: Privacy concerns, procedural fairness, and impersonal trust: an empirical investigation. Organ. Sci. 10(1), 104–115 (1999)

Xu, H., et al.: The role of push-pull technology in privacy calculus: the case of location-based services. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 26(3), 135–174 (2010)

Cropanzano, R., Ambrose, M.L.: Procedural and distributive justice are more similar than you think: a monistic perspective and a research agenda. Adv. Organ. Justice 119, 151 (2001)

Deutsch, M.: Equity, equality, and need: what determines which value will be used as the basis of distributive justice? J. Soc. Issues 31(3), 137–149 (1975)

Schwinger, T.: The need principle of distributive justice. In: Bierhoff, H.W., Cohen, R.L., Greenberg, J. (eds.) Justice in Social Relations, pp. 211–225. Springer, New York (1986)

Thibaut, J., Walker, L.: Procedural Justice: A Psychological Analysis. Erlbaum, Hillsdale (1975)

Wang, N., Xu, H., Grossklags, J.: Third-party apps on facebook: privacy and the illusion of control. In: CHIMIT’11 Proceedings of the 5th ACM Symposium on Computer Human Interaction for Management of Information Technology (2011)

Smith, H.J., Milberg, S.J., Burke, S.J.: Information privacy: Measuring individuals’ concerns about organizational practices. MIS Q. 20(2), 167–196 (1996)

Dinev, T., Hart, P.: An extended privacy calculus model for e-commerce transactions. Inf. Syst. Res. 1(17), 2006 (2006)

Phelps, J., Nowak, G., Ferrell, E.: Privacy concerns and consumers willingness to provide personal information. J. Public Policy Mark. 19(1), 27–41 (2000)

Jiang, Z., Heng, C.S., Choi, B.C.F.: Privacy concerns and privacy-protective behavior in synchronous online social interactions. Inf. Syst. Res. 24(3), 579–595 (2013)

Malhotra, N.K., Kim, S.S., Agarwal, J.: Internet users’ information privacy concerns (IUIPC): the construct, the scale, and a causal model. Inf. Syst. Res. 15(4), 336–355 (2004)

Lee, Y.E., Benbasat, I.: The influence of trade-off difficulty caused by preference elicitation methods on user acceptance of recommendation agents across loss and gain conditions. Inf. Syst. Res. 22(4), 867–884 (2011)

Komiak, S.Y.X., Benbasat, I.: The effects of personalization and familiarity on trust and adoption of recommendation agents. MIS Q. 30(4), 941–960 (2006)

Tam, K.Y., Ho, S.Y.: Web personalization as a persuasion strategy: an elaboration likelihood model perspective. Inf. Syst. Res. 16(3), 271–291 (2005)

Ho, S.Y., Bodoff, D., Tam, K.Y.: Timing of adaptive web personalization and its effects on online consumer behavior. Inf. Syst. Res. 22(3), 660–679 (2011)

Hui, K.L., Teo, H.H., Lee, S.Y.T.: The value of privacy assurance: an exploratory field experiment. MIS Q. 31(1), 19–33 (2007)

Petronio, S.: Boundaries of Privacy: Dialectics of Disclosure. State University of New York Press, Albany (2002)

Awad, N.F., Krishnan, M.S.: The personalization privacy paradox: an empirical evaluation of information transparency and the willingness to be profiled online for personalization. MIS Q. 30(1), 13–28 (2006)

Folger, R., Konovsky, M.A.: Effects of procedural and distributive justice on reactions to pay raise decisions. Acad. Manag. J. 32(1), 115–130 (1989)

Youn, S.: Teenagers’ perceptions of online privacy and coping behaviors: a risk-benefit appraisal approach. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 49(1), 86–110 (2005)

Grosser, T.J., Lopez-Kidwell, V., Labianca, G.: A social network analysis of positive and negative gossip in organizational life. Group Org. Manag. 35(2), 177–212 (2010)

Mathieson, K.: Predicting user intentions: comparing the technology acceptance model with the theory of planned behavior. Inf. Syst. Res. 2(3), 173–191 (1991)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Choi, B.C.F., Tam, J. (2015). Privacy by Design: Examining Two Key Aspects of Social Applications. In: Fui-Hoon Nah, F., Tan, CH. (eds) HCI in Business. HCIB 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 9191. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20895-4_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20895-4_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-20894-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-20895-4

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)