Abstract

Online health communities are becoming an important source of information whereby users of these platforms, especially patients, participate for knowledge sharing and emotional support. This research examines the perceived value of expert generated information and user (patient) generated information and how it is influenced by different types of information that a user seeks. First, we propose a framework to classify the types of information based on the different types of information patients typically seek out on online health communities using a knowledge based perspective. Then based on this framework, we provide a set of propositions on the perceived value of expert generated versus user driven responses derived by patients. We expect that expert generated responses to have greater perceived value by patients as compared to community driven responses depending on the type of information patients are asking. Specifically, information uncertainty requiring tacit knowledge and high affect such as treatment experiences has greater value when generated by other patients. On the other hand, information uncertainty requiring explicit knowledge and low affect such as understanding the nature of diseases has greater value when generated by expertise. The proposed framework can help to extend the line of research on online health communities and inform health professionals, health organizations or developers of such communities.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

Online communities serve as an important platform that can have significant impact on health care and health care organizations. Patients can gain access to health information from a larger group of people than ever before (Viswanath et al. 2007). In many websites of health care organizations, message boards, messaging, mailing lists and chat rooms are provided, allowing individuals and patients to forge online communities through their platform. Prominent examples of online health communities include those offered by digital businesses such as WebMD and non-profit health care organizations such as American Cancer Society.

There are several reasons why patients participate in online communities. Previous studies have documented the main functions of Internet use for health such as searching for information about the disease, for coping and social support (Kalichman et al. 2003). Some studies have shown that the World Wide Web is an important channel for patients to source information on health conditions (Berland et al. 2001; DeGuzman and Ross 1999; Loader et al. 2002). This is made possible because increased access to health information allows patients or individuals who are concerned with their health to gain knowledge about symptoms, treatments and conditions.

In addition to fulfilling information needs, the social fabric of the Internet enabled through online communities has increased the possibility of fulfilling emotional needs required by patients or individuals who are concerned about their health. Leimeister et al. (2008) corroborated that virtual relationships formed among social networks of cancer patients indeed provide informational and emotional support. They also showed that Internet usage behavior, motives and perceived advantages of computer mediated communication affect virtual relationships positively.

Patients are linked to similar others who encourage each other, provide social support, share and evaluate treatment options, and build effective coping strategies. Cohen et al. (1985) found that social networks have a direct effect on reducing physical symptoms. Previous studies on online support groups have corroborated the notion that online support is beneficial to patients through empathetic support and supportive communication. Mickelson (1996) has found that individuals from electronic support groups perceive their electronic friends with similar problems higher than their family and non-electronic friends. Other studies have shown that technology is an important channel for patients to source information on health conditions (Maloney-Krichmar and Preece 2003; Berland et al. 2001; DeGuzman and Ross 1999). Access to these communities is twenty-four hours by seven days, making it convenient and flexible for users (Maloney-Krichmar and Preece 2003). Additionally, diversity of the communities is also valued by users of such communities (Maloney-Krichmar and Preece 2003).

The way information is delivered through these technological platforms has also seen tremendous changes from purely informational websites to user-driven websites where patients themselves interact and provide information with one another via online message boards (or forums). This in part drives one of the major problems faced by patients that is the credibility of information they received via online communities. This is especially true when the information is provided by anonymous others who participate in the community as it is difficult to verify the identity of the users of the community. This problem is compounded because patients try to hide their identity under the veil of anonymity to avoid the stigma of suffering from a disease. At the same time, people who intend to market their health products use these platforms as a way to disseminate product information and this could be harmful when misinformation is generated. To ameliorate these problems of user-generated information, some online web portals engage medical experts (e.g. physicians) to moderate the communities. Health sites such as WebMD provide a solution to this problem by introducing medical experts on their technological platform to allow medical experts to respond to patients’ queries.

Korp (2006) suggested that the Internet has the potential to displace experts and professional interests and that it is imperative to examine how expert versus user (patient) generated knowledge relate to each other. However, previous studies have not investigated the comparative value of expert generated information versus user-generated information in online health communities. Furthermore the impact of medical experts on these communities has not been explored in previous research and a comparison between the perceived value from medical experts versus peers has not been examined. Thus, the goal of this paper is to tease out the value of expert and user-generated information in online health communities. While the provision of medical knowledge in the real world is largely dependent on experts like medical experts, technology provides a platform where knowledge is generated and transferred between different types of users. Although this bottom up generation and transfer of knowledge may have less credibility, it poses an interesting research question: What is the value of the information provided by experts compared to user (patient) generated information? We propose a comprehensive framework to link the major types of online health discussion (expert or user) generated information to the perceived value of information to patients. Results from testing the proposed hypotheses can help to inform health professionals and organizations or online community developers.

2 Theoretical Lens

Drawing from literature across different disciplines, we attempt to examine the question of whether expert generated or user generated information is more valuable for online health communities using a knowledge based lens.

Uncertainty. To understand the value of online health communities to patients, we first need to understand that one of the fundamental reasons for patients to visit online health communities is to seek information. The relationship between information seeking behavior and uncertainty has been well established (Berger and Calabrese 1975). Dosi and Egidi (1991) define “substantive uncertainty” as lack of information and introduce the notion of “procedural uncertainty” which reflects the gap between the complexity of the situation and the agents’ competence in processing information. This gap can be addressed with greater knowledge.

Uncertainty exists when there is inadequate, inconsistent or unavailable information arising from complex, ambiguous and volatile circumstances (Brashers 2001). In the health context, patients often feel uncertain about their situation with respect to their disease condition. Individuals may have questions about verifying symptoms, their ability to manage illness, making sense of medication, treatment and even their health care provider’s skills and abilities. These questions are usually resolved through a search for answers and then employing certain heuristics to make sense of the information provided.

In the literature on cognitive processing, it has been suggested that judgment under uncertainty is driven by heuristics. Some of the heuristics identified in the notable work of Tversky and Kahneman (1974) are: (1) representativeness, (2) availability and (3) anchoring.

-

1.

Representativeness refers to the stereotypical impression of types that people use to make judgments.

-

2.

The availability heuristic refers to the number of times a class or the probability of an event by the ease with which instances or occurrences can be recalled and brought to mind.

-

3.

Anchoring refers to heuristic where people judge the new probability with respect to the original value.

These heuristics suggest that people tend to err in their judgments because of the fundamental flaws inherent in these heuristics and will be used to explain our hypotheses.

Knowledge Based View. Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (1995) knowledge creation model has been widely cited in previous literature. They popularized two different types of knowledge: explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge. In this knowledge creation model, the authors propose that human knowledge is created and expanded through social interaction between tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge. This interaction is the knowledge conversion process whereby one state (explicit or implicit knowledge) is converted from one form to another.

In this paper, we propose a knowledge based lens on online health communities and suggest that the value of the expert generated information versus user-generated information depends on the type of knowledge the patients seek for. Specifically the perceived value of knowledge generated will depend on what type it is: explicit or tacit, as this will change the associated uncertainty gap. The organizational literature is replete with attempts to distinguish tacit knowledge from explicit knowledge. We use the definitions of the various types of knowledge following Grant’s model (1996).

Explicit knowledge is objective and refers to the knowledge about “facts and theories”. It is rational and has some form of sequential processing involved. Typically, explicit knowledge refers to knowledge that can be easily codified and transferred. Therefore, uncertainty that needs to be addressed by explicit knowledge tends to rely on experts or top management in providing explicit knowledge to bridge the gap. Instructions and guidelines (e.g. medications to treat high blood pressure) will fall into this category of knowledge. An alternative conceptualization to explicit knowledge is that it is somewhat like declarative knowledge, which includes factual knowledge.

On the other hand, tacit knowledge refers to the “know-how”, about how to do something. This can refer to the way tasks are carried out or the methods involved. This knowledge manifests itself in the doing of something. This type of knowledge is not easily transferable. Tacit knowledge cannot be articulated easily and often creates a large uncertainty gap. This knowledge is embedded in the engagement and exchanges between individuals that includes the interactions between the patients seeking for information and the medical expert, or patient seeking for information and other patients. Tacit knowledge is knowledge gained from experience that cannot be found in manuals or books. To a certain extent, tacit knowledge requires personal judgment and skilful action. However, the individual performing the action may not be even aware of the details and how he has performed the action. Tacit knowledge transfer is an emergent process where the knowledge comes from coordination and self-organizing of individuals. These individuals can be both experts and non-experts. Thus, tacit knowledge is linked to procedural knowledge where important differences of opinions exist.

Uncertainty can be managed through articulation (Afifi and Burgoon 2000). To reduce uncertainty that needs to be addressed with tacit knowledge, individuals can benefit from exchanges with one another collating diverse opinions and options. Because tacit knowledge may not be captured easily and may even be missed by the individual with tacit knowledge, pooling knowledge from many individuals may reduce uncertainty further by building on top of existing knowledge. A similar notion of “collective intelligence” or user-generated information has been suggested in the community of practice literature. In communities of practice, people come together as a group to share knowledge, learn together and create common practices. Thus, it has been suggested that in these communities, the complexity of knowledge requires that no one expert can provide the “best” answer and thus, collective intelligence is a better alternative in giving this answer.

Information Needs. We propose that the perceived value of information generated by experts or users is contingent on the information needs of the information seeker. In the information science literature (Wilson 2006), there are three types of information needs which interrelate with one another: physiological, affective and cognitive. Physiological needs refer to basic needs like need for water, air and other essentials. Affective needs refer to the needs related to emotional and psychological needs such as the need for attainment and support. Cognitive needs refer to the need to plan and learn a certain skill. However, this approach is limited when applied to domains such as health information seeking.

Context is an important factor for information seeking (Johnson 2003). In the marketing health literature, Moorman (1994) defines health information acquisition as a process where consumers obtain and assimilate “knowledge relevant to physical and mental well-being” and it involves “[…] decision making and the implementation and confirmation of health related behaviors”. From the previous studies, there is a need to fill this gap of information seeking in the health context. Thus, we will integrate the above literature and formulate a framework for classifying health information needs. In the information seeking literature, Graydon et al. (1997) has identified five information needs categories—(1) nature of disease, its process and prognosis, (2) treatments, (3) investigative tests, (4) preventive, restorative, and maintenance physical care, and (5) patient’s psychosocial concerns. A recent study (Medlock et al. 2015) identified similar topics by examining the information seeking behavior and the types of information seniors seek online. The first four types of information needs can be categorized according to the uncertainty framework except for the last dimension of affective needs.

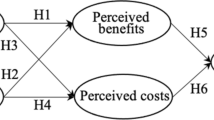

There are two dimensions of information need that we used to classify the types of information users seek in online health communities. Firstly, information can be classified based on the type of knowledge is used to fill the uncertainty gap. Explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge are the different types of knowledge that are required to fill an uncertainty gap. Secondly, the affective need refers to the type of information that invokes emotions such as supportive information. Based on the two different dimensions, we classify four different types of information needs (Fig. 1): (i) information needs that require explicit knowledge and low affective need, (ii) information needs that require tacit knowledge and low affective need (iii) information needs that require explicit knowledge and high affective need and (iv) information needs that require tacit knowledge and high affective need. Patients with illnesses experience high uncertainty about their prognoses, potential treatments, social relationships and identity concerns.

3 Proposed Theoretical Model

Based on the framework in Fig. 1, we propose the hypothesized relationships in the research model shown in Fig. 2.

Expert generated information. Studies have found that cues to assessing credibility for web sites include the site’s identity, currency and authoritativeness of its information, its sponsors, business partners and privacy practices. Expert knowledge is usually judged as having greater credibility (Stanford et al. 2002). Since greater credibility instills confidence in the information that is being read, experts can positively influence the perceived value of information received.

P1: The presence of expert is positively associated with the value of information generated within the online community.

User (patient) generated information. The value of user (patient) generated information in online health communities can increase with the diversity of the patients’ backgrounds and the sheer quantity of peer patients. This prediction is in line with the theory of weak ties of Granovetter (1973) and that of Friedkin (1982). Granovetter (1973) suggests that weak ties can provide more useful information as opposed to strong ties because diverse set of people provides different information. Weak ties serve as a way to bridge across different groups of people thereby increasing access to different resources. Additionally, Friedkin (1982) attributed the success of weak ties through the sheer number of ties. Quantity is a major factor to increased availability of resources because as more people see the request, the chances that there is somebody who has the knowledge will be able to provide a helpful response. The number of users is likely to be positively associated with the value of information generated by the community because of the higher levels of social support that can be garnered. This means that more responses will be provided to an information seeker.

P2: The number of users is positively associated with the value of information generated by the community.

Information Need. The value of information provided by experts or users (peer patients) can differ as a result of differences in terms of information needs. Certain types of information provided by medical experts will be perceived as having greater value compared to those provided by other patients. As suggested in the proposed framework in Fig. 1, this information need could be categorized into four types. Each of these four types of information needs affect the perceived value of expert generated information versus user (patient) generated information.

The first type of information need, i.e. explicit knowledge, is required to fill the uncertainty gap when affective need is low, expert opinions are judged as having greater value. This is because users regard an expert opinion as more credible because of the specialized knowledge held by the experts. Information needs that are explicit and low affect, usually require answers based on some codebook of instruction. Examples of information needs in this category include questions about nature of disease, medication and treatment types. Although the information may not be widely available, it can be learned through books or manuals. Higher uncertainty requiring explicit knowledge is more likely to induce information seekers to use the heuristics as described earlier. In this case, this type of information needs can be best addressed by experts who possess sound and more accurate answers for such questions. Thus, we propose that:

P3a: The value perceived by information seekers with explicit and low affect information need is greater if answers are provided by experts as compared to other users.

The second type of information need is characterized by explicit knowledge and high affect. We contend that this type of information need may be fulfilled by either users or experts. It is an integration of the top-down and bottom-up knowledge and support that enables the reduction of uncertainty at the individual level. Experts can provide value by providing information based on their knowledge and both experts and users can provide social support. Social support can be used to assist in uncertainty management. In general, when affective needs are high, both expert and user generated social support can fill the information need of the individual. For instance, social support is often requested in online health communities by patients or family of patients. There are two reasons: first, the user will share a common attribute such as an illness and invoke some form of empathy, which is not present when the user is dealing with the experts. Second, the mass of users as compared to a single expert can create a greater amount of social support.

Similarly, it has been argued that to reduce uncertainty, knowledge does not need to be entirely accurate (Brashers 2001). As long as the knowledge is coherent, it can reduce uncertainty to a certain extent. Kahneman and Frederick (2002) argued that attribute substitution happens when one attribute which is usually used as the judgmental criteria is not available, another more readily accessible attribute is used in the assessment. Thus, in this case when the expert is not available, other users who provide information becomes important. Thus, we posit that:

P3b: There is no difference in value perceived by information seekers, on explicit and high affect information needs, between the answers provided by experts and users.

The third type of information need requires tacit knowledge and low affect. We argue that there is no difference between the perceived value of the information generated by the experts of users. The reasoning is similar to hypothesis 3b. In this case, just as tacit knowledge creation is enabled through a “spiral conversion process” (Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995), tacit knowledge elicitation is enabled through the exchanges between information seeker, expert and users. Thus, this knowledge not only helps the user to reduce uncertainty, it also helps the user to make sense of a circumstance such as interpreting an unknown symptom that others have experienced (Brashers et al. 2000). Thus, we posit that

P3c: There is no difference in value perceived by information seekers with tacit knowledge and low affect information need between the answers provided by experts and users.

On the other hand, when affect is high and tacit knowledge is required, user is judged as having greater value than experts. In a previous study, it was shown that online social network helps patients manage uncertainty through information provision (Brashers et al. 2004). Representativeness, one of the judgment heuristics that people use, plays a central role for information need requiring tacit knowledge and high affect. This judgment heuristic refers to the impression of others being similar to the object of interest (Tversky and Kahneman 1986). Based on implications, people view the value of information on treatment experiences and psychosocial support provided by users similar to themselves, to have greater value when the information sourced are treatment experiences and psychosocial support as compared to an expert. The diverse opinions across many different individuals create a pooled intelligence resulting in substantial value. Users are more valuable in answering such information needs because they have undergone similar experiences. The affective need is provided through the mass of users.

P3d: The perceived value tacit and high affect information (such as treatment experiences) is greater if it is user generated as compared to expert generated.

4 Conclusions

This study attempts to tease out the value between user (in this case the patient) generated information and expert generated information. Starting with an information needs framework, we provide an integrative information need framework and proposed a research model that suggests that the perceived value of expert generated or user generated content by patients is contingent on information need of the patient.

A recent study finds that 59 % of US adults look online for health and medical information (Fox and Duggan 2013). As such, the findings from this study will be highly relevant as it will help to answer the question of when user generated information may be a better approach than expert generated information and vice versa when individuals seek health information in online health communities. Further, this study provides a theoretical basis for future research on online health communities and has practical implications such as informing health professionals, health organizations or online health communities’ developers in the use of technological platforms.

References

Afifi, W.A., Burgoon, J.K.: Behavioral violations in interactions: The combined consequences of valence and change in uncertainty on interaction outcomes. Hum. Commun. Res. 26, 203–233 (2000)

Berger, C.R., Calabrese, R.J.: Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Hum. Commun. Res. 1(2), 99–112 (1975)

Berland, G.K., Elliott, M.N., Morales, L.S., Algazy, J.I., Kravitz, R.L., Broder, M.S.: Health information on the internet: accessibility, quality, and readability in English and Spanish. JAMA 295m, 2612–2621 (2001)

Brashers, E.: Collective AIDS activism and individuals’ perceived self-advocacy in physician-patient communication. Hum. Commun. Res. 26(3), 372–402 (2000)

Brashers, D.E.: Communication and uncertainty management. J. Commun. 51(3), 477–497 (2001)

Brashers, D.E., Neidig, J.L., Goldsmith, D.J.: Social support and the management of uncertainty for people living with HIV or AIDS. Health Commun. 16(3), 305–331 (2004)

Butler, B.S.: Membership size: communication activity, and sustainability. Inf. Syst. Res. 12(4), 346–362 (2001)

Cline, R.J.W., Haynes, K.M.: Consumer health information seeking on the internet: the state of the art. Health Educ. Res. 16, 671–692 (2001)

DeGuzman, M.A., Ross, M.W.: Facilitating coping with chronic physical illness. In: Zeidner, M., Endler, N.S. (eds.) Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, and Applications, pp. 640–696. Wiley, New York (1999)

Dosi, G., Egidi, M.: Substantive and procedural uncertainty: an exploration of economic behaviours in changing environments. J. Evol. Econ. 1(2), 145–168 (1991)

Fox, S., Jones, S.: The Social Life of Health Information. Pew Internet & American Life Project, Washington, D.C. (2009)

Fox, S., Duggan, M.: Health Online. Pew Internet & American Life Project, Washington, D.C. (2013)

Grant, R.M.: Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 17, 109–122 (1996)

Graydon, J., Galloway, S., Palmer-Wickham, S., Harrison, D., Rich-van der Bij, L., West, P., et al.: Information needs of women during early treatment for breast Cancer. J. Adv. Nurs. 26, 59–64 (1997)

Johnson, J.: On contexts of information seeking. Inf. Process. Manag. 39, 735–760 (2003)

Kalichman, S.C., Benotsch, E.G., Weinhardt, L., Austin, J., Luke, W., Cherry, C.: Health-related internet use, coping, social support, and health indicators in people living with HIV/AIDS: preliminary results from a community survey. Health Psychol. 22, 111–116 (2003)

Korp, P.: Health on the internet: implications for health promotion. Health Educ. Res. 21(1), 78–86 (2006)

Kulthau, C.C.: Inside the search process: information seeking from the user’s perspective. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 42(5), 361 (1991)

Maloney-Krichmar, D., Preece, J.: An ethnographic study of an online health support community. In: Duquense Ethnography Conference, Philadelphia, pp. 10–12 (2003)

Medlock, S., Eslami, S., Askari, M., Arts, D.L., Sent, D., de Rooij, S.E., Abu-Hanna, A.: Health information–seeking behavior of seniors who use the internet: a survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 17(1), e10 (2015)

Nonaka, I., Takeuchi, H.: The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. Oxford University Press, New York (1995)

Leimeister, J.M., Schweizer, K., Leimeister, S., Krcmar, H.: Do virtual communities matter for the social support of patients?: Do virtual communities matter for the social support of patients? Inf. Technol. People 21(4), 350–374 (2008)

Steginga, S.K., Occhipinti, S., Gardiner, R.A., Yaxley, J., Heathcote, P.: Making decisions about treatment for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 89(3), 255–260 (2002)

Tapscott, D., Williams, A.D.: Wikinomics. Tantor Media, Connecticut (2006)

Tversky, A., Kahneman, D.: Rational choice and the framing of decisions. J. Bus. 59(4), S251–S278 (1986)

Viswanath, K., Ramanadhan, S., Kontos, E.Z.: Mass media and population health: a macrosocial view. In: Galea, S. (ed.) Macrosocial Determinants of Population Health, pp. 275–294. Springer, New York (2007)

Wilson, T.: On user studies and information needs. JDOC 62(6), 658–670 (2006)

Acknowledgement

The first author is grateful for generous financial support from Simon Fraser University’s President’s Research Startup Grant and Foundation Ramon Areces.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Goh, J.M., Yndurain, E. (2015). The Value of Expert vs User Generated Information in Online Health Communities. In: Fui-Hoon Nah, F., Tan, CH. (eds) HCI in Business. HCIB 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 9191. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20895-4_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20895-4_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-20894-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-20895-4

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)