Abstract

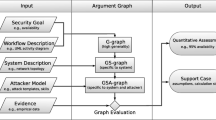

This chapter outlines a concept for integrating cyber denial and deception (cyber-D&D) tools, tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTTPs) into an adversary modeling system to support active cyber defenses (ACD) for critical enterprise networks. We describe a vision for cyber-D&D and outline a general concept of operation for the use of D&D TTTPs in ACD. We define the key elements necessary for integrating cyber-D&D into an adversary modeling system. One such recently developed system, the Adversarial Tactics, Techniques and Common Knowledge (ATT&CK™) Adversary Model is being enhanced by adding cyber-D&D TTTPs that defenders might use to detect and mitigate attacker tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). We describe general D&D types and tactics, and relate these to a relatively new concept, the cyber-deception chain. We describe how defenders might build and tailor a cyber-deception chain to mitigate an attacker’s actions within the cyber attack lifecycle. While we stress that this chapter describes a concept and not an operational system, we are currently engineering components of this concept for ACD and enabling defenders to apply such a system.

The original version of this chapter was revised. An erratum to this chapter can be found at DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32699-3_13

Authors: Frank J. Stech, Kristin E. Heckman, and Blake E. Strom, the MITRE Corporation (stech@mitre.org, kheckman@mitre.org, and bstrom@mitre.org). Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Case Number 15-2851. The authors’ affiliation with The MITRE Corporation is provided for identification purposes only, and is not intended to convey or imply MITRE’s concurrence with, or support for, the positions, opinions or viewpoints expressed by the authors. Some material in this chapter appeared in Kristin E. Heckman, Frank J. Stech, Ben S. Schmoker, Roshan K. Thomas (2015) “Denial and Deception in Cyber Defense,” Computer, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 36–44, Apr. 2015. http://doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/MC.2015.104

An erratum to this chapter can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32699-3_13

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Jim Walter (2014) “Analyzing the Target Point-of-Sale Malware,” McAfee Labs, Jan 16, 2014. https://blogs.mcafee.com/mcafee-labs/analyzing-the-target-point-of-sale-malware/ and Fahmida Y. Rashid (2014) “How Cybercriminals Attacked Target: Analysis,” Security Week, January 20, 2014. http://www.securityweek.com/how-cybercriminals-attacked-target-analysis

- 2.

Jim Sciutto (2015) OPM government data breach impacted 21.5 million,” CNN, July 10, 2015. http://www.cnn.com/2015/07/09/politics/office-of-personnel-management-data-breach-20-million/ Jason Devaney (2015) “Report: Feds Hit by Record-High 70,000 Cyberattacks in 2014,” NewsMax, 04 Mar 2015. http://www.newsmax.com/Newsfront/cyberattacks-Homeland-Security-Tom-Carper-OMB/2015/03/04/id/628279/

- 3.

Advanced persistent threats (APTs) have been defined as “a set of stealthy and continuous computer hacking processes, often orchestrated by human(s) targeting a specific entity. APT usually targets organizations and/or nations for business or political motives. APT processes require a high degree of covertness over a long period of time. The “advanced” process signifies sophisticated techniques using malware to exploit vulnerabilities in systems. The “persistent” process suggests that an external command and control system is continuously monitoring and extracting data from a specific target. The “threat” process indicates human involvement in orchestrating the attack.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advanced_persistent_threat A useful simple introduction and overview is Symantec, “Advanced Persistent Threats: A Symantec Perspective—Preparing the Right Defense for the New Threat Landscape,” no date. http://www.symantec.com/content/en/us/enterprise/white_papers/b-advanced_persistent_threats_WP_21215957.en-us.pdf A detailed description of an APT is Mandiant (2013) APT1: Exposing One of China’s Cyber Espionage Units, www.mandiant.com, 18 February 2013. http://intelreport.mandiant.com/Mandiant_APT1_Report.pdf

- 4.

The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) defined active cyber defense (ACD) in 2011: “As malicious cyber activity continues to grow, DoD has employed active cyber defense to prevent intrusions and defeat adversary activities on DoD networks and systems. Active cyber defense is DoD’s synchronized, real-time capability to discover, detect, analyze, and mitigate threats and vulnerabilities…. using sensors, software, and intelligence to detect and stop malicious activity before it can affect DoD networks and systems. As intrusions may not always be stopped at the network boundary, DoD will continue to operate and improve upon its advanced sensors to detect, discover, map, and mitigate malicious activity on DoD networks.” Department of Defense (2011) Strategy for Operating in Cyberspace, July 2011, p. 7.

Cyber researcher Dorothy Denning differentiated active and passive cyber defense: “Active Cyber Defense is direct defensive action taken to destroy, nullify, or reduce the effectiveness of cyber threats against friendly forces and assets. Passive Cyber Defense is all measures, other than active cyber defense, taken to minimize the effectiveness of cyber threats against friendly forces and assets. Whereas active defenses are direct actions taken against specific threats, passive defenses focus more on making cyber assets more resilient to attack.” Dorothy E. Denning (2014) “Framework and Principles for Active Cyber Defense,” Computers & Security, 40 (2014) 108–113. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167404813001661/pdfft?md5=68fecd71b93cc108c015cac1ddb0d430&pid=1-s2.0-S0167404813001661-main.pdf

In both the DOD’s and Denning’s definitions, actions are defensive. Thus ACD is NOT the same as hacking back, offensive cyber operations, or preemption. However, ACD options are active and can involve actions outside of one’s own network or enterprise, for example, collecting information on attackers and sharing the information with other defenders.

- 5.

''Tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs)'' is a common military expression and acronym for a standardized method or process to accomplish a function or task. We added `tools' because cyber adversaries use a variety of different tools in their tactics, techniques, and procedures. On the analysis of TTPs, see Richard Topolski, Bruce C. Leibrecht, Timothy Porter, Chris Green, and R. Bruce Haverty, Brian T. Crabb (2010) Soldiers' Toolbox for Developing Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTP), U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences Research Report 1919, February 2010.http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a517635.pdf

- 6.

Jeffrey Rule quotes its creator, John R. Boyd, describing the OODA loop: “orientation shapes observation, shapes decision, shapes action, and in turn is shaped by the feedback and other phenomena coming into our sensing or observing window. …the entire “loop” (not just orientation) is an ongoing many-sided implicit cross-referencing process of projection, empathy, correlation, and rejection.” Jeffrey N. Rule (2013) “A Symbiotic Relationship: The OODA Loop, Intuition, and Strategic Thought,” Carlisle PA: U.S. Army War College. http://oai.dtic.mil/oai/oai?verb=getRecord&metadataPrefix=html&identifier=ADA590672 Rule and other exponents of the OODA loop concept see the utility of D&D to isolate the adversary inside their own OODA loop and thus separate the adversary from reality. Osinga sees Boyd’s OODA theory as affirming the use of deception against the adversary’s OODA loop: “Employ a variety of measures that interweave menace, uncertainty and mistrust with tangles of ambiguity, deception and novelty as the basis to sever an adversary’s moral ties and disorient or twist his mental images and thus mask, distort and magnify our presence and activities.” Frans P. B. Osinga (2007) Science, Strategy and War: The strategic theory of John Boyd, Oxford UK: Routledge, p. 173.

- 7.

“Cyber threat intelligence” is still an evolving concept. See, for example, Cyber Intelligence Task Force (2013) Operational Levels of Cyber Intelligence, Intelligence and National Security Alliance, September 2013. http://www.insaonline.org/i/d/a/Resources/Cyber_Intelligence.aspx; Cyber Intelligence Task Force (2014) Operational Cyber Intelligence, Intelligence and National Security Alliance, October 2014. http://www.insaonline.org/i/d/a/Resources/OCI_wp.aspx; Cyber Intelligence Task Force (2014) Strategic Cyber Intelligence, March 2014. http://www.insaonline.org/CMDownload.aspx?ContentKey=71a12684-6c6a-4b05-8df8-a5d864ac8c17&ContentItemKey=197cb61d-267c-4f23-9d6b-2e182bf7892e; David Chismon and Martyn Ruks (2015) Threat Intelligence: Collecting, Analysing, Evaluating. mwrinfosecurity.com, CPNI.gov.uk, cert.gov.uk. https://www.mwrinfosecurity.com/system/assets/909/original/Threat_Intelligence_Whitepaper.pdf

- 8.

The concept of “cyber operations security (OPSEC)” has had little systematic development or disciplined application in cyber security. One analyst wrote, “Social media, the internet, and the increased connectivity of modern life have transformed cyber space into an OPSEC nightmare.” Devin C. Streeter (2013) “The Effect of Human Error on Modern Security Breaches,” Strategic Informer: Student Publication of the Strategic Intelligence Society: Vol. 1: Iss. 3, Article 2. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/si/vol1/iss3/2 See also Mark Fabro, Vincent Maio (2007) Using Operational Security (OPSEC) to Support a Cyber Security Culture in Control Systems Environments, Version 1.0 Draft, Idaho Falls, Idaho: Idaho National Laboratory, INL Critical Infrastructure Protection Center, February 2007. http://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/oeprod/DocumentsandMedia/OpSec_Recommended_Practice.pdf

- 9.

E.M. Hutchins, M.J. Cloppert, and R.M. Amin, “Intelligence-Driven Computer Network Defense Informed by Analysis of Adversary Campaigns and Cyber Kill Chains,” presented at the 6th Ann. Int’l Conf. Information Warfare and Security, 2011; www.lockheedmartin.com/content/dam/lockheed/data/corporate/documents/LWhite-Paper-Intel-Driven-Defense.pdf

- 10.

Bodner et al. argue “Working in unison is the only way we can reverse the enemy’s deception,” and offer an overview on applying integrated cyber-D&D to defense operations and implementing and validating cyber-D&D operations against the adversary’s OODA loop; Sean Bodmer, Max Kilger, Gregory Carpenter, and Jade Jones (2012) Reverse Deception: Organized Cyber Threat Counter-Exploitation, New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 354.

- 11.

See, for example, David Chismon and Martyn Ruks (2015) Threat Intelligence: Collecting, Analysing, Evaluating. mwrinfosecurity.com, CPNI.gov.uk, cert.gov.uk. https://www.mwrinfosecurity.com/system/assets/909/original/Threat_Intelligence_Whitepaper.pdf

- 12.

See https://attack.mitre.org/wiki/Main_Page for details on the ATT&CK model and framework.

- 13.

Definitions of the D&D tactics shown in Fig. 2 are provided in Kristin E. Heckman, Frank J. Stech, Roshan K. Thomas, Ben Schmoker, and Alexander W. Tsow Cyber Denial, Deception& Counterdeception: A Framework for Supporting Active Cyber Defense. Switzerland: Springer, ch. 2.

- 14.

E.M. Hutchins, M.J. Cloppert, and R.M. Amin, “Intelligence-Driven Computer Network Defense Informed by Analysis of Adversary Campaigns and Cyber Kill Chains,” Op cit.

- 15.

Barton Whaley, “Toward a General Theory of Deception,” J. Gooch and A. Perlmuter, eds., Military Deception and Strategic Surprise, Routledge, 2007, pp. 188–190.

- 16.

MITRE, Threat- Based Defense: A New Cyber Defense Playbook, 2012; www.mitre.org/sites/default/files/pdf/cyber_defense_playbook.pdf

- 17.

Sergio Caltagirone, Andrew Pendergast, and Christopher Betz, “Diamond Model of Intrusion Analysis,” Center for Cyber Threat Intelligence and Threat Research, Hanover, MD, Technical Report ADA586960, 05 July 2013.

- 18.

The tactics “mimic, invent, decoy” are all commonly used terms describing actions to mislead. The tactic “double play,” or “double bluff,” requires some explanation. A double play or a double bluff is a ruse to mislead an adversary (the deception “target”) in which “true plans are revealed to a target that has been conditioned to expect deception with the expectation that the target will reject the truth as another deception,” Michael Bennett and Edward Waltz (2007) Counterdeception: Principles and Applications for National Security. Boston: Artech House, p. 37. A poker player might bluff repeatedly (i.e., bet heavily on an obviously weak hand) to create a bluffing pattern, and then sustain the bluff-like betting pattern when dealt an extremely strong hand to mislead the other players into staying in the betting to call what they believe is a weak hand. The double play formed the basis of a famous Cold War espionage novel, John le Carré’s, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. An intelligence service causes a defector to reveal to an adversary the real identity of a double agent mole spying on the adversary. The defector is then completely discredited as a plant to deceive the adversary, causing the adversary to doubt the truth, that the mole could actually be a spy. The Soviet Union may have used a version of the double play to manipulate perceptions of a defector (Yuriy Nosenko), i.e., “too good to be true,” to mislead the CIA to doubt the bona fides of Nosenko and other Soviet defectors (e.g., Anatoliy Golitsyn). See Richards J. Heuer, Jr. (1987) “Nosenko: Five Paths to Judgment,” Studies in Intelligence, vol. 31, no. 3 (Fall 1987), pp. 71–101. Declassified, originally classified “Secret.” http://intellit.muskingum.edu/alpha_folder/H_folder/Heuer_on_NosenkoV1.pdf However, “blowing” an actual mole with a double play is atypical of what CIA counterintelligence agent, Tennent Bagley, called “Hiding a Mole, KGB-Style.” He quotes KGB colonel Victor Cherkashin as admitting the KGB dangled “Alexander Zhomov, an SCD [Second Chief Directorate] officer,” in an “elaborate double-agent operation in Moscow in the late 1980s to protect [not expose] Ames [the KGB’s mole in the CIA].” Tennent H. Bagley (2007) Spy Wars: Moles, Mysteries, and Deadly Games. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 226. http://cdn.preterhuman.net/texts/government_information/intelligence_and_espionage/Spy.Wars.pdf

- 19.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Stech, F.J., Heckman, K.E., Strom, B.E. (2016). Integrating Cyber-D&D into Adversary Modeling for Active Cyber Defense. In: Jajodia, S., Subrahmanian, V., Swarup, V., Wang, C. (eds) Cyber Deception. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32699-3_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32699-3_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-32697-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-32699-3

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)