Abstract

In online social networks, new social connectivity is established when a respondent accepts a friend request from an unfamiliar requestor. While users are generally willing to establish online social connectivity, they are at times reluctant in constructing profile connections with unfamiliar others. Drawing on the privacy calculus perspective, this study examines the effects of social structure overlap and profile extensiveness on privacy risks as well as social capital gains and how the respondent responds to a friend request (i.e., intention to accept). The results provide strong evidence that social structure overlap and profile extensiveness influence privacy risks and social capital gains. In addition, while privacy risks reduce intention to accept, social capital gains increase intention to accept online social connectivity.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Online social networks

- Online social connectivity

- Impression formation

- Privacy calculus

- Intention to accept

1 Introduction

Online social connectivity is highly important to online service providers. A new online social connectivity is initiated when an unfamiliar requestor sends a friend request to a request respondent [1]. The respondent’s response to the friend request is often influenced by his or her impression of the requestor, and the impression is formed based on the requestor’s personal profile on online social networks. Personal profiles typically contain a variety of information about the requestor, such as photographs, personal interests, and social circles.

Past studies reveal that developing online social connectivity with an unfamiliar requestor can be beneficial to the respondent. Furthermore, the establishment of online social connectivity enables the respondent to develop additional relationships based on the social networks of the requestor. As a key function of online social networks is to facilitate the development and maintenance of online social connectivity, we contend that gains in social resources are an important benefit in developing new online social connectivity.

It has, however, been observed that while online social connectivity enables increasing in social resources, its establishment might subject the respondent to risks. Research in the interpersonal communication domain provides insights into this phenomenon. For example, Stern and Taylor [2] examined students’ Facebook usage behavior and reported that while students did accept friend requests from unfamiliar others, those who were concerned about their privacy information denied friend requests. In essence, the respondent might deny profile connections in response to privacy risks on online social networks.

In this paper, we propose and empirically test a research model that integrates the interpersonal cognition literature and the privacy calculus perspective. In sum, the model maintains that the effects of category-based information and attribute-based information are summarized into privacy risks and social capital gains, which in turn, drive the respondent’s response to online social connectivity (i.e., intention to accept).

2 Literature Review

2.1 Impression Formation

The literature on interpersonal cognition suggests that individuals form impression of others by considering two types of social information, namely category-based information and attribute-based information. Category-based information triggers social categorization, which invokes relational frames stored in memory [3]. Researchers suggest that category-based information facilitates sense-making by providing mechanisms for comprehending relational communications [4]. Attribute-based information activates individualization in social information processing. By considering others’ specific attributes systematically, individuals are likely to develop deep understanding of others.

2.2 Privacy Calculus

The privacy calculus perspective posits that individuals’ decision in allowing boundary accessibility is the outcome of a tradeoff, in which individuals consider the risks associated with boundary accessibility against certain social gains [5]. While past research has considered a variety of risks and gains, privacy risks and social capital gains are suggested to be particularly relevant to individuals’ behavior when their personal information is concerned. This study defines privacy risks as the threats to personal information associated with the establishment of profile connections. This type of privacy risks is particularly important in online social networks because establishment of online social connectivity exposes individuals’ privacy space to unforeseen danger. Social capital gains are defined as the estimated increase in resources accumulated through relationship development [6]. Past research has regarded gains in social capital as the main enticement for individuals to engage in social interactions.

While privacy risks are known to be a prime inhibitor to online social networking, the respondent’s social capital gains are found to be a major driver of online social connection development. Overall, privacy risks and social capital gains, which represent the two components in the respondent’s privacy calculus, are particularly important in influencing his or her response to online social connectivity.

3 Research Model and Hypotheses

The research model is presented in Fig. 1.

3.1 Determinants of Privacy Risks

Social structure overlap refers to the degree to which the respondent and the requestor share common interpersonal contacts. The respondent who shares similar social networks with the requestor tends to share a common perspective with regards to relationship development, and this commonality reduces risks in developing connections. The resulting social cohesion engendered by social structure overlap lessens the likelihood that the requestor will engage in exploitive behavior, hence reducing risks to the respondent’s privacy. Thus, we predict that:

H1: Compared to low social structure overlap, high social structure overlap leads to lower privacy risks.

In addition to social structure overlap, we expect privacy risks to be influenced by requestor’s profile extensiveness, which refers to the extent to which the personal profile contains detailed personal information. Researchers have noted the importance of personal profiles in the initial stage of relationship development. When requestor’s profile extensiveness is high, the respondent may develop rich understanding of the requestor, hence reducing privacy risks with regards to establishing online social connectivity. Therefore, we posit that:

H2: Compared to low profile extensiveness, high profile extensiveness leads to lower privacy risks.

High social structure overlap helps the respondent converge his or her focus on social similarity with the requestor, that is, the respondent is likely to perceive the requestor as someone who shares common social circles and interpersonal connections [7]. Hence, the effect of profile extensiveness is likely diminished when social structure overlap is high.

In contrast, low social structure overlap suggests less commonality in interpersonal relationships. As a result, the respondent is likely to become more prudent in forming impression of the requestor. Low social structure overlap would not be sufficient in finalizing the respondent’s impression of the requestor. Compared to low profile extensiveness, high profile extensiveness connotes more informative profile content and hence reduces privacy risks with regards to establishing online social connectivity. Thus, we hypothesize that:

H3: There is an interaction effect between social structure overlap and profile extensiveness on privacy risks, i.e., in the high social structure overlap condition, the effect of profile extensiveness in terms of reducing privacy risks is less prominent than that in the low social structure overlap condition.

3.2 Social Capital Gains

In online social networks, social structure overlap is a concise representation of similarity in social networks as well as commonality in interpersonal connections. Research on interpersonal relationship has consistently uncovered strong links between social structure overlap and liking, which is also termed as the similarity effect. Typically, individuals believe others, who shared common social connections, would also believe what individuals believe [8]. Past research suggests that a positive relationship between social structure overlap and individuals’ expectation of social capital gains in relationship development. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H4: Higher social structure overlap leads to higher social capital gains.

From a social penetration perspective, when an unfamiliar requestor reveals himself or herself through self-disclosure, the respondent is better able to understand the requestor and predict his or her future behavior. In online social networks, the lack of physical presence limits attribute-based information to the requestor’s self-disclosure in personal profiles. As a result, the respondent has to rely heavily on the requestor’s personal profile in assessing his or her social capital gains. Accordingly, high profile extensiveness is likely to induce large social capital gains in establishing online social connectivity. Thus, we predict that:

H5: Higher profile extensiveness leads to higher social capital gains.

When social structure overlap is high, the respondent feels assured that the requestor would have common interests and share mutual understanding in developing relationships, thereby reducing the respondent’s reliance on profile information in assessing social capital gains. However, when social structure overlap is low, mutual understanding and common interests cannot be guaranteed; hence, the respondent would pay more attention to information available in the requestor’s personal profiles. Thus, we propose that:

H6: There is an interaction effect between social structure overlap and profile extensiveness on social capital gains, i.e., in the high social structure overlap condition, the effect of profile extensiveness in terms of increasing social capital gains is less prominent than that in the low social structure overlap condition.

3.3 Privacy Tradeoff and Request Acceptance

Accepting a friend request can be risky because it represents the respondent’s willingness in exposing himself or herself to the requestor in online social networks. Much research suggests that in online social networks, relationship acceptance can be impeded by the respondent’s privacy risks perceptions in establishing online social connectivity [9]. Therefore, we posit that:

H7: Higher privacy risks lead to lower intention to accept.

A number of studies suggest that social capital gains significantly influence intention to accept a friend request. For example, in a study on Facebook, Lampe et al. [10] reported that individuals who had favorable impression of others were more willing to establish online profile connections. These findings imply that the respondent’s gains in social capital may induce acceptance to a friend request. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H8: Higher social capital gains lead to higher intention to accept.

4 Research Methodology

This research employed a quasi-experimental design (i.e., 2 × 2 factorial design) that integrates the characteristics of field surveys and lab experiments. Facebook was chosen as the online social network platform for this study. Respondents were university students who had online social networking experience. In the experiment, respondents were presented with one of the four scenarios (i.e., varied across the two categories of social structure overlap and profile extensiveness) in which they received a friend request from an unfamiliar requestor.

Social structure overlap was manipulated by the number of mutual friends the respondent has in common with the requestor. In this study, low social structure overlap was represented by 5 % of the respondent’s total Facebook friends, whereas high social structure overlap was represented by 50 % of the respondent’s total Facebook friends. Profile extensiveness was facilitated by manipulating the amount of content items in the mock-up personal profile of the requestor that mimicked actual Facebook layout and technology features (e.g., sponsored advertisements, profile pictures, and timeline elements).

Low profile extensiveness was represented by 5 timeline items, while high profile extensiveness was represented by 20 timeline items. The timelines items were developed based on a pool of actual timeline items contributed by students from the same university. Respondents were told to imagine that the scenario was real and read through it carefully. Afterwards, they were instructed to complete a questionnaire that contained manipulation checks and measurements of the research variables, as well as the relevance and realism of the friend request scenario.

The survey ran for one week, and collected 76 responses, who were not friends of the contributors.

5 Data Analysis and Results

5.1 Respondent Demographics and Background Analysis

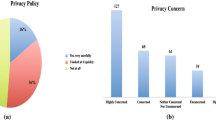

Among the 76 respondents participating in the study, 37 were females. The age of the respondents ranged from 19 to 22, with average Internet experience and average Facebook experience being 6.28 years and 4.2 years, respectively.

5.2 Results on Privacy Risks

ANOVA with privacy risks as dependent variable reveals that higher social structure overlap significantly leads to lower privacy risks (F (1, 72) = 75.04, p < 0.01) (see Table 1).

Further, profile extensiveness is found to have a significant main effect on privacy risks (F (1, 72) = 20.49, p < 0.01), meaning that compared to low profile extensiveness, high profile extensiveness reduces privacy risks. Hence, H1 and H2 are supported. Simple main effect analysis (Table 2 and Fig. 2) reveals that (1) high profile extensiveness is associated with significantly higher social capital gains than low profile extensiveness under the low social structure overlap condition (F (1, 37) = 22.67, p < 0.01), and (2) low profile extensiveness and high profile extensiveness are not different from each other in affecting social capital gains under the high social structure overlap condition (F(1, 36) = 1.47, p = 0.23). Therefore, H3 is supported.

5.3 Results on Social Capital Gains

ANOVA with social capital gains as dependent variable reveals that higher social structure overlap significantly leads to higher social capital gains (F (1, 72) = 90.11, p < 0.01) (see Tables 5 and 6). Further, profile extensiveness is found to have a significant main effect on social capital gains (F (1, 72) = 69.26, p < 0.01) (see Table 3). Hence, H4 and H5 are supported.

In line with our prediction, the effect of profile extensiveness is more prominent in the low social structure overlap condition than in the high social structure overlap condition (Table 4 and Fig. 3). Therefore, H6 is supported.

5.4 Results on Request Acceptance

Partial Least Square (PLS) was used to test remaining hypotheses. The measurements generally load heavily on their respective constructs, with loadings above 0.8, thus demonstrating adequate reliability (Table 5).

Subjects’ intention to accept was captured using three items. The high composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha scores shown in Table 6 lend support to satisfactory internal consistency.

The diagonal elements in Table 6 represent the square roots of average variance extracted (AVE) of latent variables, while off-diagonal elements are the correlations between latent variables. For adequate discriminant validity, the square root of the AVE of any latent variable should be greater than correlation between this particular latent variable and other latent variables. Data shown in Table 6 therefore satisfies this requirement. Moreover, in Table 5, the loadings of indicators on their respective latent variables are higher than loadings of other indictors on these latent variables and the loadings of these indicators on other latent variables, thus lending further evidence to discriminant validity.

Results shown in Fig. 4 indicate that privacy risks has a significant and negative effect on intention to accept (β = −0.352, p < 0.01). Hence, H7 is supported. Furthermore, the results demonstrate that social capital gains have a significant and positive effect on intention to accept (β = 0.525, p < 0.01). Therefore, H8 is supported.

6 Theoretical Implication

This study makes important theoretical contributions. Past IS research examining privacy issues in online social networks has paid little attention to social connectivity regulation. This lack of attention to the establishment of social connections is somewhat surprising since a prime reason for individuals to adopt online social networks is to establish, develop, as well as maintain social connections. On the basis of the privacy calculus perspective, we identify privacy risks and social capital gains, as the cost and benefit elements of a privacy tradeoff, whereby individuals consider the privacy threats and social benefits in establishing social connectivity. Our findings show that privacy risks and social capital gains are indeed important determinants of individuals’ response to a request for profile connections. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to employ the notion of privacy boundary regulation to understand the establishment of social connectivity.

Further, we contribute to the IS literature by providing evidence on the importance of impression formation in regulating social connectivity. While past studies have identified a myriad of factors pertinent to privacy perceptions, rarely have researchers examined the effects of social information processing on individuals’ assessment of privacy threats and social benefits. Based on the interpersonal cognition literature, this study identifies two important antecedents of privacy calculus, namely social structure overlap and profile extensiveness. Specifically, social structure overlap is a type of social category-based information, which invokes relational frames to facilitate social categorization. Profile extensiveness concerns the details of requestor’s specific information (i.e., social attribute-based information), which is essential for individualization in social information processing. Taken as a whole, we combine literature on impression formation and privacy calculus and then show the efficacy of this integrative approach in the context of online social networks.

7 Practical Implication

Our findings have important implications to application designers as well as online social networks providers. Application designers of online social networks often provide mechanisms that address users’ perception of privacy risks. While mechanisms that address privacy risks are somewhat common, little design efforts have been made on enhancing the appreciation of social capital gains. To this end, we advocate a design strategy which improves recognition of social capital gains. As predicted by the proposed model, social capital gains are found to be enhanced by greater social structure overlap and profile extensiveness. While this result is largely consistent with conventional wisdom, a more interesting finding of this study is probably that the joint effect of social structure overlap and profile extensiveness on social capital gains is more pronounced in the low social structure overlap condition than that in the high social structure overlap condition. This finding suggests that the extensiveness of profile details is crucial for relationship development between users who do not share a high degree of social commonality. This is because an extensive profile provides comprehensive information about the requestor, thereby reducing uncertainty and enhancing interpersonal understanding. Thus, it is important that application designers consider enriching profile extensiveness, such as photo album previews and timeline abstracts on online social networks.

8 Limitations and Future Directions

Our contributions can be limited by friend request scenario. Evidence suggests that the effects of social structure overlap and profile extensiveness may depend on the friend request scenario. For example, Pagani [11] revealed that individuals were generally reluctant to reject connectivity with those they had actual social relationships. In our experiment, respondents were presented with a friend request scenario in which an imaginary friend had sent them a Facebook friend request. Result has shown that respondents perceived the friend request scenario as relevant (mean = 6.02) and realistic (mean = 5.54), thus lending confidence that our scenario selection is appropriate.

This study opens up a number of exciting avenues for further research. We see the value in investigating “objective” measures of social connectivity acceptance, as opposed to our current behavioral intention measurements. It is possible that individuals’ actual behavior may not completely reflect their behavioral intentions. To this end, a further investigation of actual acceptance using a field experiment could be a future research avenue.

Furthermore, it is likely that some individuals’ responses to a friend request might manifest in behavior beyond acceptance. For example, they might report the requestor as a spammer or block the requestor from future relational approaches. We encourage researchers to explore other behavioral responses which might be important in online social networks.

9 Conclusion

Despite various measures taken by online social networks providers, privacy issues continue to be a major impediment to the development of social connectivity. Given the importance of profile connections, practitioners have expressed substantial concerns on individuals’ disinterests in accepting social connectivity. To that end, we offer a theory-driven approach to evaluating the two key types of social information in helping practitioners to promote the development of social connectivity. Our findings clearly indicate that an integration of the interpersonal cognition literature and the privacy calculus perspective is essential for a better understanding of individuals’ intentional to accept. We believe that the model proposed in this study can serve as a solid foundation for future work in this important area.

References

Boyd, D., Heer, J.: Profiles as conversation: networked identity performance on friendster. In: Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, vol. 3, p. 59c (2006)

Stern, L.A., Taylor, K.: Social networking on facebook. J. Commun. Speech Theatre Assoc. North Dakota 20, 9–20 (2007)

Hayes, S.C., Barnes-Holmes, D.: Relational operants: processes and implications: a response to Palmer’s review of relational frame theory. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 82(2), 213–224 (2004)

Solomon, D.H., Dillard, J.P., Andersen, J.W.: Episode type, attachment orientation, and frame salience: evidence for a theory of relational framing. Hum. Commun. Res. 28(1), 136–152 (2002)

Laufer, R.S., Wolfe, M.: Privacy as a concept and a social issue: a multidimensional development theory. J. Soc. Issues 33(3), 22–42 (1977)

Coleman, J.S.: Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 94, 95–120 (1988)

Chen, Y.-R., Chen, X.-P., Portnoy, R.: To whom do positive norm and negative norm of reciprocity apply? effects of inequitable offer, relationship, and relational-self orientation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 45(1), 24–34 (2009)

Ross, L., Greene, D., House, P.: The “false consensus effect”: an egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 13(3), 279–301 (1977)

Ellison, N.B., Steinfield, C., Lampe, C.: The benefits of facebook “friends:” social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J. Comput. Mediated Commun. 12(4), 1143–1168 (2007)

Lampe, C., Ellison, N., Steinfield, C.: A familiar face(book): profile elements as signals in an online social network. In: CHI 2007, San Jose, CA, USA (2007)

Pagani, M.: The influence of personality on active and passive use of social networking sites. Psychol. Mark. 28(5), 441–456 (2011)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Wu, Y., Choi, B.C.F., Yu, J. (2016). The Effects of Social Structure Overlap and Profile Extensiveness on Facebook Friend Requests. In: Nah, FH., Tan, CH. (eds) HCI in Business, Government, and Organizations: eCommerce and Innovation. HCIBGO 2016. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 9751. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39396-4_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39396-4_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-39395-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-39396-4

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)