Abstract.

More than anybody else, individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) easily suffer from environmental stimuli and sensory overloads due to their particular sensory perceptual systems which also cause attention related problems as well as communication difficulties in everyday lives. In our previous interaction design explorations for augmenting attention of autistics, we suggested that it would be beneficial to keep track of autistics’ individual differences and needs, and provide information accordingly [1]. Even though the existing methods that examine autistic sensory perception provide extensive knowledge, they are insufficient to provide in-depth user specific live data for a learning and a sensory-aware system which satisfy such particular differences. Thus, as we carry on ideating attentive user interfaces for autistics, our current studies focus on possible research methods which can access sensory perceptual data in individual levels. Here in this paper, we share our preliminary insights from the studies on exploring sensory ethnography and, depending on our three ongoing and interconnected prototypical studies, we suggest that this can reveal and represent novel ways of seeing the already known information of how autistics perceive the world and insights for the design of a sensory ethnography tool.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords:

- Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

- mediated reality

- sensory perception

- sensory ethnography

- design research

- biosensors

- attentive user interfaces

1 Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is clinically defined as a neurodevelopmental disorder manifesting itself during early developmental period of life and it is characterized by impairments in social interaction and communication, repetitive behaviors and restricted interests. These characteristics vary in severity from person to person and this is why it is called spectrum. With the DSM-5 (The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - 5th Edition) definition [2] sensory aspects of the disorder appears among other characteristics and current studies [3] suggest that sensory perceptual experiences (SPEs) underlie these characteristics.

SPEs cover the symptoms such as hypo- and hypersensitivity to environmental stimuli, distorted and fragmented perception, sensory overloads, difficulty in interpreting the stimuli, fascination with or inability to tolerate certain colors, objects, textures etc. [4]. These symptoms are prominently reported in autistic accounts such as autobiographies [5] [6] [7] as well as in clinical studies. Due to such conditions, ASD individuals often suffer from attention problems and tantrums particularly while socializing, learning and working.

In order to provide less challenging spaces for autistics, we are exploring the design space of novel user interfaces and/or interactive spaces that refine autistic sensory perception by means of augmented and diminished reality (Fig. 1). Deriving from the discussions of our previous studies [1] on such solutions for autistics, we now explore the world of autistics’ SPEs. Our explorations are based on ethnographic studies which lead us to search for new data collection methods grounding themselves to ethnographic research. At the end of this study, we discuss the possible scenarios when we use biosensors to track SPEs of ASD individuals and combining the data with sensory ethnography studies in order to inform design processes.

2 Background

With the main aim of developing learning and sensory-aware interaction design solutions for refining autistic sensory perception in everyday life situations, we suggest to use sensory ethnography and biosensors. Here, we briefly go through significant and recent literature on these two concentrations.

2.1 Autistic Sensory Perception

In film and TV, most of the autism representations invite non-autistics to understand autism only by looking at it [8] from a non-autistic perspective. Thus, existing media representations are lacking in conveying the ASD perception to non-autistic audiences, even if they are based on real stories and consulted by domain experts as well as ASD individuals [9]. Even though there are simulation examples of SPEs such as the performative show in the theater adaptation of Mark Haddon’s fictional book [10] on autistic traits, these examples can only cover a limited part of autistic SPEs and they are not adaptive. Such absence motivated us to go deeper in this relevant research question of how to visually represent, illustrate the autistic perception, or in other words, create a live, learning autistic reality.

On the other hand, autobiographies and novels written by autistics are of high importance in terms of sampling SPEs through autistics’ eyes. Bogdashina [3] revealed the patterns of SPEs in autism by analyzing sensory descriptions and related behaviors in such accounts. She examines these experiences in four different aspects: a) possible sensory experiences; b) perceptual styles; c) cognitive styles; d) other sensory conditions. In possible sensory experiences, she explains how the real world, the raw stimuli (as non-autistics sense), such as colors, tastes, sounds etc. sensed differently by autistics due to their particular sensitivities and processing styles such as fragmented, distorted or delayed. In perceptual styles, she lists autistic’s coping strategies against the sensory experiences. As information processing, memory and attention in autism is examined in cognitive styles, in the last part she explains unusual SPEs such as resonance and daydreaming [4]. Categorization of SPEs is underpinned by qualitative and quantitative studies with autistics as well [11, 12]. These studies also show that each autistic person has unique combinations of perceptual and behavioral traits that we can not be fully covered with categorizations.

Since each autistic is uniquely affected from different types of environmental stimuli, and preferences and SPEs change over time, we need profound user data when developing interactive solutions for autistics. However, existing studies and categories are insufficient to base our user research on. Additionally, collecting data from autistic individuals is a challenging task due to the differences in their perception, cognition and communication abilities, particularly of those who are on the severe points of the spectrum. Mostly because they don’t communicate how they sense the world. We are in need of adaptive, aware and learning environments to keep track of and deal with SPE related problems.

2.2 Sensory Ethnography and Biosensors

Sensory ethnography is where the researcher engages with interconnected senses (i.e. multisensory), uses different media together and goes beyond textual representations by engaging with art practice [13]. It covers the activities that researcher does with the participant in order to sense together. Walking, eating or dancing with the participant (mobile methods) are examples of such activities. During these activities, sensory ethnographer creates evocative material such as photos or videos in order to re-sense and represent the participant’s encounter with the environment.

In this regard, sensory ethnography is a fruitful method which can inform the design process by providing knowledge about how the participant (user in design context) senses the environment. For example, in LEEDR (Lower Effort Energy Demand Reduction) Project, sensory ethnography is applied in order to reveal how participants interact with sensory (e.g. temperature, lightings, coziness) and digital (usage of control devices) aspects of home [14]. This enables redefining the energy consumption problem and developing new Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) design solutions for domestic usage [15].

Besides its outcomes for design practices, O’Dell and William suggest that sensory ethnography can provide better ‘sensory understanding’ when it is represented with drawings, cartoons or sculptures as well as photos and videos [16]. They also propose that such representations are more ‘evocative and convincing’ comparing to textual transcriptions. This is where sensory ethnography meets with art practice in order to convey the ethnographic content to related audiences.

Spinney [17] brings sensory ethnography one step forward: He claims that mobile methods are reductive due to participants’ verbalizations and unintentional filterings, thus, these methods don’t profoundly reveal how the participants are affected by the environment. According to his theoretical suggestion, ‘unfiltered’ data collection is possible by combining these methods with biosensors. Based on the studies of Aspinall et al. [18] and Nold [19], he suggests that, doing mobile ethnography, with the support of biosensors such as EEG and GSR, provides quantitative data as much as qualitative.

As ethnographic research methods are shifting from conventional observations into engagements with the research subject by adapting multiple media and methods [20], autism, as one of the most unlocked realms of qualitative research [21], needs new methods that can reveal individual differences profoundly. Herein, combination of sensory ethnography and biosensors as a research method [17] sounds promising to build a learning and aware system for ASD individuals. However this combination was used in different contexts in previous studies [18, 19], ASD is not included in these contexts yet.

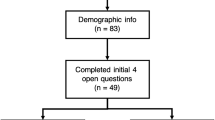

3 Method

When doing design research for autistics, perceptual, cognitive and social autistic traits hinder conventional ethnographic methods such as interviews and observations. In order to design for autistics, we believe that our design research should be constructed upon unconventional ethnographic methods which can help us going beyond these barriers by probing how each autistic individual senses and perceives environmental stimuli. Drawing on our literature review on autistic sensory perception and sensory ethnography, we are conducting three preliminary, interconnected and life-long ethnographic studies. We hope these studies will inform our next steps in design research.

3.1 #autisticmoments

We started shaping our ethnographic research on Instagram since it’s a suitable platform to access numerous users, observe and archive the way they see the world as well as to reflect how we engage with the sensoriality of our surroundings. We created a hashtag called #autisticmoments on Instagram and, based on our literature review, we try to see the world through autistic eyes. We take and upload photos and videos that can represent autistic sensory perception. We search for irregular patterns, flickering color combinations, fragmented images etc. particularly based on the sensory experiences categorized in Bogdashina’s study [4]. This hashtag has lately turned into a participatory study with the contribution of people who are interested in the topic. We and many other users we don’t know, still upload new photos on this hashtag and invite participants to represent their sensory perceptions regardless of being autistics or not (Fig 2). Additionally, we try to spread this hashtag among ASD individuals to represent their SPEs.

3.2 Sense Journal

In order to collect autistic sensory perceptual data, we designed a ‘Sense Journal’ which is an A5-size notebook that allows participants to carry around and record their sensory perceptual preferences and experiences based on time, location (Fig. 3a) and six senses (vision, hearing, touch, smell, taste and proprioception).

After publishing an announcement of this study on various social media channels, we reached 12 autistic participants through their parents who responded to the announcement. Based on their level of ability to read and write (which was reported by their parents), we selected 5 autistics who are older than 18 years and sent them the journals. In order to reveal the differences between articulations of SPEs between autistics and non-autistics, we sent the journals to 5 non-autistics, who are older than 18 years and willing to participate in this study, as well.

The open-ended questions about different senses in the journal invited participants to describe their perceptions of different stimuli. We supported these questions with visual elements and photos from #autisticmoments in order to reveal expressions that are descriptive of experiences (Fig. 3b). Moreover, some questions are designed to provide associations between senses. For example, a question requires describing a taste with selecting the most associative visual elements among others on the page (Fig. 3c). Ultimately, in case of inability to describe experiences verbally, we introduce #autisticmoments hashtag to participants so that they can upload photos or videos of their SPEs and preferences.

3.3 Sense Visualizations

In addition to the #autisticmoments study, we started to visualize autistics’ own accounts on their SPEs in order to make an archive of evoking and communicating ethnographic material. We chose the autobiographical novel Nobody Nowhere [5], written by an autistic writer, Donna Williams, due to the diversity of descriptions of her SPEs in the book.

First, two research assistants, who are psychologists, read the book and decided work on the first 76 pages, that cover the first 15 years of Donna Williams’ life, since the way she described her experiences in this part was more detailed and fruitful compared to the rest of the book. After an iterative reading process, they created a guideline for picking the descriptive sentences in the book. In this step, we included an illustrator in the study. Based on the guideline, the research assistants and the illustrator individually picked the sentences which include at least one description of an environmental stimulus. Secondly, the picked sentences were extracted to their components according to four characteristics in the guideline (sensory channel, stimulus, perception and description style; Table 1). The ones that cover all these characteristics were listed by the research assistants and the illustrator. When these three individually created lists were brought together, out of 162 sentences in total, 52 sentences fully matched. Finally, the illustrator started visualizing the 52 significantly descriptive sentences in an abstract style so as to communicate how Donna Williams perceive the world without showing the stimulus itself (Fig. 4).

4 Insights and Discussions

Our ethnographic research is an ongoing project. We are still collecting user data through #autisticmoments and the Sense Journal, thus we have not analyzed the full data yet. However, during our research process, we gain insights on how to bring our research a step forward and we will now use these insights for the conceptualization of sensory ethnography with biosensors idea.

4.1 #autisticmoments

We started taking photos of SPEs such as fragmented perception, hyper-or-hyposensitivity and delayed perception. In the process of seeking for these experiences wherever we go, we realized that we are actually surrounded by flashy lights, bright surfaces, irritating patterns or unexpected movements. We became more aware of possible distractions around us and how frequently and easily an autistic could be overloaded by such environmental stimuli. Moreover, the pictures we took revealed our individual differences in terms of sensory experiences. All of us focused on different aspects of environmental stimuli even though we were looking for the same SPE categories [4] This study also showed us how often we face which kind of SPEs. Another outcome of this study was to see these pictures as captured autistic moments to be inspired during the ideation process of Refined Reality Mirror design.

4.2 Sense Journal

Since the data collected from the journal is limited so far, comparisons we made between non-autistics and autistics are preliminary. However, here we share some patterns we observed in the collected journals.

First of all, autistics don’t fulfill the tasks requiring a stimulus recalling and abstract item matching whereas non-autistics easily perform these tasks. Instead of recalling and matching a certain stimulus with various visual elements, autistics prefer to name each of these elements with various stimuli (Fig. 3c). For example, when they are asked to match a certain sound they recall with the given abstract patterns, textures, numbers, colors and letters on the page, they describe these items with different sounds. Evocative photos also help them recall their SPEs (Fig. 3b). They comment on these photos expressing their prior SPEs whereas non-autistics tend to describe what they see on the photos (Fig. 5). Based on this founding, using evocative visual materials seem appropriate for ethnographic data collection studies with autistics.

Secondly, the time-location based form (Fig. 3a) helps both groups to record their SPE patterns. They use this form to describe their frequent sensory experiences in all sensory channels (not just visual experiences) and in certain types of locations (at home, at work/school, on the road and in social places) on different times of the day. In order to collect specific SPEs, the time-location based form could be embedded particularly in autistics’ lives as a part of their daily routines instead of suggesting them to use the journal whenever and wherever they want.

4.3 Sense Visualizations

After analyzing and visualizing the significantly descriptive sentences in Donna William’s auto-biographical book Nobody Nowhere, we conducted a quick study with 31 non-autistic participants in order to collect basic qualitative feedback on how these visualizations communicate themselves with a non-autistic audience. When participants were asked to comment on these abstract visualizations via an online survey, which doesn’t inform participants about the study, their accounts were mostly on what and how they felt when they looked at them. Moreover, the way they felt qualitatively overlapped with the sensory channel and sensory perceptual experiences described in the sentences as well as illustrator’s intentions when visualizing them. Some examples of participants’ accounts on the given visualizations are as follows: Fig. 4 a: “I feel jammed but still hopeful, seems like I will be free soon.” or “ Vomiting. Something wants to come out or to be thrown up. Irritating.” Fig. 4 b: “This is around me all the time. Looks nice from distance but inside it’s just annoying.” or “ I feel my face is getting stretched. I am on a knife-edge.” Fig. 4 c: “Something too obvious is purposely hiding the background. We know it is there but not focusing.” or “This is the thing I don’t know. I’m not sure if I’ll encounter with them in my life ever. Maybe yes or not, it’s neutral to me for now. I’m passing by them.” Here, we see that abstract visualizations can be means of experiencing the autistic sensory perception.

These preliminary ethnographic studies help us to represent and engage with autistic perception. All in all, we gained four main insights:

-

1.

Photos can help us reveal SPEs and visual preference patterns such as what kind of stimuli an autistic intentionally or unintentionally prefer (or not) to capture.

-

2.

Abstract visualizations can be used as a tool by which non-autistics visually engage with autistic SPEs.

-

3.

As insight 1 gives us hints about which moments to track or which stimuli to refine when designing an adaptive and attentive system, insight 2 helps us creating the interface through which autistics engage with their environments in such a system.

-

4.

Evocative materials such as photos can help participants to recall and describe their prior SPEs, thus, such materials can benefit possible uses of sensory ethnography with biosensors.

4.4 Implications for Future Studies on Sensory Ethnography with Biosensors

With the preliminary insights we gain from these studies and literature, we suggest that, combining sensory ethnography and biosensors may provide profound data to build a learning and aware attentive interface making use of the mediated reality technologies to refine autistic sensory perception. The possible advantages of such combination are as follows:

-

1.

Biosensors can collect different types of bodily data (e.g. heart rate, posture and muscle tracking, GSR, EEG) during daily encounters. These data provide unfiltered, undistorted, pre-conscious aspects of the encounters.

-

2.

When embedded in wearable devices, biosensors become a part of the body and participant can use it during daily tasks. Participant becomes independent of the researcher or controlled settings. This can increase diversity of encounters and provide more data. Moreover, this may decrease reinforcement of perceptual, cognitive and communicational differences in research participation of ASD.

-

3.

The data collected by biosensors can be combined with GPS data in order to locate encounters. This forms a basis for both participant and researcher where participant reflects upon his/her own data and researcher re-sense the encounter with participant’s reflections. This may reduce abstraction when researcher analyze encounters.

-

4.

Rigorous analysis of sensory perception may become possible by measurable data. Additionally, quantitative and qualitative analysis can be made by overlapping the data collected from both biosensors and sensory ethnography. Matching the sensory input from the surrounding with bodily reactions might provide patterns to inform about autistic sensory perception or even non-autistic sensory perception in a broader sense.

-

5.

It is possible to diversify methods within sensory ethnography. So different combinations of these methods can be used with biosensors in order to collect different types of data.

-

6.

Being aware of own bodily data in sensory level may also contribute to Quantified Self movement where people record their bodily data through mobile applications and wearable devices.

We use these insights to design a learning and aware mediated reality, attentive interface for the use of autistics. Ethics and possible disadvantages of this method should be further discussed in future studies.

5 Conclusion

Our main ongoing research aims to design an attentive interface which can provide sideways for sensory perception related attention problems of autism in daily life. Our main aim is to refine external stimuli to augment attention of autistics when necessary so that they can be more involved in social daily life activities such as working in open offices, education in mixed classrooms or a social activity in a cafe. However, to design such an interface that can satisfy each autistic individual’s needs is challenging. Because, first, each autistic is particularly affected by different external stimuli. Secondly, existing studies provide categories of SPEs in autism, yet are not sufficient to contribute to our user research since we don’t create personas, but instead, we seek for tailor-cut solutions for each autistic separately. Third, due to their perceptual, cognitive and communicational differences, it may not be suitable to conduct some of the conventional user studies with those who has severe autism. Yet, to be able to build a real-time attentive interface, the system needs to be aware and learning. This paper shares our insights from a group of preliminary user studies where we explore sensory ethnography tools, before building bio-sensing solutions into our system (Fig. 6).

References

Yantac, A.E., Çorlu, D., Fjeld, M., Kunz, A.: Exploring diminished reality (DR) spaces to augment the attention of individuals with autism. In: 2015 International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Workshops (ISMARW), pp. 68–73. IEEE (2015)

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders:: DSM-5. ManMag (2003)

Horder, J., Wilson, C.E., Mendez, M.A., Murphy, D.G.: Autistic traits and abnormal sensory experiences in adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44(6), 1461–1469 (2014)

Bogdashina, O.: Sensory perceptual issues in autism and Asperger Syndrome: different sensory experiences, different perceptual worlds. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London (2003)

Williams, D.: Nobody nowhere: The extraordinary autobiography of an autistic. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London (2007)

Tammet, D.: Born on a blue day: Inside the extraordinary mind of an autistic savant. Simon and Schuster, New York (2007)

Grandin, T.: Thinking in pictures. Bloomsbury Publishing, London (2009)

Murray, S.: Representing autism: culture, narrative, fascination. Liverpool University Press, Liverpool (2008)

Draaisma, D.: Stereotypes of autism. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B: Biol. Sci. 364(1522), 1475–1480 (2009)

Haddon, M.: The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time. National Geographic Books, Washington, D.C. (2007)

Crane, L., Goddard, L., Pring, L.: Sensory processing in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 13(3), 215–228 (2009)

Kirby, A.V., Dickie, V.A., Baranek, G.T.: Sensory experiences of children with autism spectrum disorder: in their own words. Autism 19(3), 316–326 (2015)

Pink, S.: Doing sensory ethnography. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks (2009)

Pink, S.: Digital–visual–sensory-design anthropology: ethnography, imagination and intervention. Arts Humanit. High. Educ., p. 1474022214542353 (2014)

Mitchell, V., Mackley, K.L., Pink, S., Escobar-Tello, C., Wilson, G.T., Bhamra, T.: Situating digital interventions: mixed methods for HCI research in the home. Interact. Comput., p. iwu034 (2014)

O’Dell, T., Willim, R.: Transcription and the senses: cultural analysis when it entails more than words. Senses Soc. 8(3), 314–334 (2013)

Spinney, J.: Close encounters? mobile methods, (post) phenomenology and affect. Cult. Geographies 22(2), 231–246 (2015)

Aspinall, P., Mavros, P., Coyne, R., Roe, J.: The urban brain: analysing outdoor physical activity with mobile EEG. Br. J. Sports Med. 49(4), 272–276 (2013). bjsports-2012

Nold, C.: Emotional cartography (2009). http://emotionalcartography.net/

Pink, S.: Multimodality, multisensoriality and ethnographic knowing: social semiotics and the phenomenology of perception. Qual. Res. 11(3), 261–276 (2011)

Bölte, S.: The power of words: Is qualitative research as important as quantitative research in the study of autism? Autism 18(2), 67–68 (2014)

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Pelin Karaturhan, Verda Seneor and Damla Yıldırım for their collaboration in description analysis and Sense Visualizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Çorlu, D., Yantaç, A.E. (2016). Preliminary Studies on Exploring Autistic Sensory Perception with Sensory Ethnography and Biosensors. In: Marcus, A. (eds) Design, User Experience, and Usability: Design Thinking and Methods. DUXU 2016. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 9746. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40409-7_24

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40409-7_24

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-40408-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-40409-7

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)