Abstract

Introduction: Past evidence suggests parental mediation may influence their children’s online exchanges with others; for example, parental mediation of adolescents’ technology and internet use buffers against cyberbullying (Collier et al. 2016). Yet, no research has investigated how parental mediation and adolescents’ social capital relates to cyberbullying. The present study explores the associations between social capital and parental mediation with cyberbullying and cybervictimization. Methods: 215 adolescents (56% female) aged 13 to 17 in a parent-teen diary study were recruited across the United States via a Qualtrics panel. Two Hierarchical Linear Regression analyses were conducted with cyberbullying and cybervictimization as the outcome variables while taking into consideration sex, age, ethnicity (Block 1) and internet use (Block 2). Social capital variables were entered into Block 3 and parental mediation variables were entered into Block 4. Results: Both internet use and social capital positively predicted cyberbullying and cybervictimization (p < 0.05), suggesting trade-offs between frequency of internet use and the ability to bond with others online in direct relation to the risk of engaging in or exposing oneself to cyberbullying. As shown in Table 1, social bonding, internet use, and device use monitoring are significantly associated with cybervictimization (p < .05). Social bonding and online monitoring were significantly associated with cyberbullying (p < .05). Conclusions: Our research highlights the complex relationships between adolescent internet use, the benefits of engaging online with others, and the potential risks of cyberbullying. However, parental mediation linked to these cyber risks indicates that caregivers mediate when there are online concerns.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Background

Internet and digital media have created novel and innovative pathways of communication for adolescents to connect with others in a meaningful way. Social media sites and instant messaging services have grown in use and popularity among adolescents (Lenhart et al. 2015). For example, posting updates on various social media sites, such as Snapchat, Facebook, or YouTube, has become part of day-to-day life for many young people. As such, online platforms have the potential to promote interpersonal bonds because digital media offers a way in which adolescents share with others. Social capital extends beyond simply sharing with others, but consists of having relationships with others whom one can count on to provide support in the future (Williams 2006). Putnam (2000) described two distinct categories of social capital, specifically bridging and bonding, to reflect different types of interpersonal bonds. For instance, bridging refers to the formation and maintenance of weak social ties to others, possibly in large social networks (Liu et al. 2016). Therefore, bridging may expand social networks to include other worldviews or create opportunities for information or resources in the future (Williams 2006). Contrastingly, bonding is considered to occur when strongly tied individuals (e.g., adolescents with family and peers) provide each other with emotional support. The reciprocity observed in bonding social capital promotes strong emotional bonds that enables mobilization of support and resources (Williams 2006). Past research revealed a link between internet use and social capital highlighting that electronic devices help to promote and strengthen relationships among adolescents (Liu et al. 2016). Yet, social capital generated by engaging in online social networks by adolescents may be influenced to the extent in which caregivers provide their teens with access to technology and digital media.

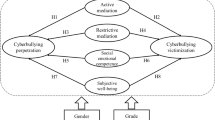

Researchers have started to explore the role of caregivers in relation to their children’s media use (Livingstone et al. 2011). Key aspects of parental mediation include distinct strategies that are implemented by caregivers, specifically active mediation, restrictive mediation, and monitoring mediation. First, active mediation refers to the parent discussions regarding online content, such as interpreting and critiquing, to support adolescents’ consumption of digital media (Livingstone et al. 2011). Next, restrictive mediation refers to when the caregiver sets rules that restrict the adolescent’s use either by time or activities (Livingstone et al. 2011). Lastly, online monitoring considers when the caregiver checks available records of the adolescent’s internet use afterwards whereas device use monitoring considers the use of software to filter, restrict or monitor the adolescent’s use of technologies and digital media (Livingstone et al. 2011). As a result, parental mediation may influence their children’s online exchanges with others; for example, parental mediation of adolescents’ technology and internet use buffers against cyberbullying (Collier et al. 2016).

This shift towards online communication has provided an opportunity for potentially harmful online interactions, such as, cyberbullying and cybervictimization incidents. Cyberbullying refers to an intention by a group or individual to repeatedly send hurtful messages or posts to an individual through electronic devices or digital media (Tokunaga 2010). Relatedly, cybervictimization refers to being a target of online aggression that occurs through technology (Shapka and Maghsoudi 2017). Empirical evidence indicates that cyberbullying as well as cybervictimization prevalence rates range from 5% to 74% among adolescents (Hamm et al. 2015; Tokunaga 2010). Furthermore, Pelfrey and Weber (2013) found in a nationally representative sample involving 3,400 United States adolescents that approximately 3% reported cyberbullying others every day. As such, it appears that cyberbullying is a widespread concern that impacts a substantial proportion of young people. Yet, no research has investigated how parental mediation and adolescents’ social capital relates to cyberbullying and cybervictimization. The present study addressed this gap by investigating the link among social capital and parental mediation with cyberbullying and cybervictimization. The main research question that guides the present work is:

-

RQ: What are the associations between social capital and parental mediation on cyberbullying and cybervictimization, while taking into consideration sociodemographic background (e.g., age, ethnicity, and gender)?

2 Methods

2.1 Data Collection

The sample included 215 adolescents from the United States (56% female) aged 13 to 17 who participated in a web-based survey with their parent or legal guardian. This study received post-secondary institutional approval from their behavioral review ethics board. After the adult participants provided their informed consent for themselves and their child, teens were also given the opportunity to assent to be a part of the study. Teen participants who did not provide their assent were not included in the analysis. Parents completed their surveys first then were asked to leave the room so that their teens could complete their portion of the survey. In this paper, we only analyzed data collected from teen participants. To recruit a nationally representative sample of participants, we leveraged a Qualtrics panelFootnote 1. Qualtrics compared data collected with regional demographics to prevent over sampling from a particular population. Attention screener questions were used to filter out low quality data. The data collection was completed by the end of August 2014.

2.2 Measures

Cyberbullying and Cybervictimization.

Participants’ cyberbullying and cybervictimization experiences were measured with an online harassment scale (Wisniewski et al. 2017). This behavioral-based measure consists of 6-items with two subscales: cyberbullying (3 items) and cybervictimization (3 items). Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = not at all, 2 = one to a few times this past year, 3 = a few times a month, 4 = a few times a week, to 5 = almost every day. A higher score represents greater involvement in cyberbullying or cybervictimization. The measure asks respondents about their online interactions between self and others. The cybervictimization items are grouped together, followed by the set of cyberbullying items. The measure asks respondents about their online interactions between self and others. Sample cybervictimization items include “Based on your experiences within the past year, please indicate how frequently you were subjected to online interactions between you and others that involved someone treating another person in a mean or hurtful way, making rude or threatening comments, spreading untrue rumors, harassing, or otherwise trying to “cyberbully” another person” and “online interactions between you and others that involved sharing personal or sensitive information either without the owner’s consent or that otherwise breached someone’s personal privacy.” A sample of cyberbullying item include “Based on your experiences within the past year, please indicate how frequently you sought out online interactions between you and others that involved exchanging sexual messages (i.e. “Sexting”), sexually suggestive text-based messages or revealing/naked photos, or arranging to meet someone first met online for an offline romantic encounter.” The cybervictimization measure has a Cronbach’s α of 0.93 and cyberbullying has a Cronbach’s α of 0.94.

Social Bonding.

Participants’ bridging and bonding social capital were measured with the Internet Social Capital Scale (ISCS; Williams 2006). This measure consists of 20-items with two subscales: bridging (10 items) and bonding (10 items). Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strong disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, to 5 = strongly agree. A higher score represents higher social capital. Sample bonding items include “the people I interact with online would put their reputation on the line for me” and “there is someone online I can turn to for advice about making very important decisions.” Sample of bridging items include “interacting with people online makes me feel connected to the bigger picture” and “Interacting with people online makes me interested in things that happen outside of my town.” The ISCS measure had been shown to have a Cronbach’s α of 0.90 (Williams 2006).

Parental Mediation.

Parental mediation strategies measured were active, restriction, and monitoring (Livingstone et al. 2011). The measure consists of 20-items with three subscales: active (5 items), restriction (6 items) and monitoring (11 items). Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = not at all, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, to 5 = almost all of the time. Next, sample active item includes “Do either of your parents currently do any of the following things with you? Talk to you about what you do on the Internet.” Sample of restriction item includes “For each of these situations, please specify how restrictive your parents usually are: Upload photos, videos or music to share with others.” Lastly, examples of monitoring item include “Does either of your parents sometimes check any of the following things - which websites you visited based on your Internet browsing history” and “Use parental control technologies to keep track of the websites you visit.” The parental mediation measure had been shown to have Cronbach’s α of 0.75 for active mediation, 0.94 for monitoring mediation, and 0.88 for restriction mediation.

Demographics.

Self-reports of age and ethnicity were used to determine demographic characteristics of participants. Age was determined by asking participants to select their current age from categories of 13 years old, 14 years old, 15 years old, 16 years old, and 17 years old. Participants identified their gender as either male or female. Participants were also asked “Choose the category which best describes you” Respondents endorsed one response that they most closely identify with: White/Caucasian, Black/African-American, Hispanic/Latino, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, Other. The ethnic descriptions were collapsed into the following four categories: White, Black, Hispanic/Latino, and Other (Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, American Indian, Alaska Native, Other).

2.3 Data Analysis

Two Hierarchical Linear Regression analyses were conducted with cyberbullying and cybervictimization as the outcome variables while taking into consideration sex, age, ethnicity (Block 1) and internet use (Block 2). Social capital variables were entered into Block 3 and parental mediation variables were entered into Block 4.

3 Results

As shown in Table 1, both internet use and bonding social capital positively predicted cyberbullying and cybervictimization (p < 0.05). Parental mediation strategies were also positively associated with cyber-risks; online monitoring predicted cyberbullying while device monitoring by parents was significantly associated with cybervictimization. Internet use became a non-significant factor for cyberbullying once parental mediation (Block 4) was added to the model. The main effects of demographic factors, specifically age, ethnicity, and gender, did not significantly contribute to the models.

4 Discussion and Conclusion

Our research highlights the complex relationships between adolescent internet use, the benefits of engaging online with others, and the potential risks of cyberbullying. Study findings indicate that there is a significant association between cyberbullying experiences, social capital, and parental mediation. Our results suggest trade-offs between frequency of internet use and the ability to bond with others online in direct relation to the risk of engaging in or exposing oneself to cyber-related risks. Interestingly, parental mediation did not seem to have an effect on reducing cyber-risks. Instead, our results are consistent with prior work (Wisniewski et al. 2015) that suggests parents may take more reactive approaches to mediate teens’ online risk experiences once they occur. Yet, a limitation of our findings is that cross-sectional data is not best suited to confirm causal relationships. Therefore, longitudinal studies are needed to investigate the dynamic relationship between social capital and parental mediation as adolescents develop and encounter stressful online situations, such as cyberbullying and cybervictimization. Future studies examining the interplay between parental mediation techniques, adolescent internet use, online risks, and online benefits would serve to further disentangle these effects.

References

Collier, K.M., Coyne, S.M., Rasmussen, E.E., Hawkins, A.J., Padilla-walker, L.M., Erickson, S.E., Memmott-elison, M.K.: Does parental mediation of media influence child outcomes? A meta-analysis on media time, aggression, substance use, and sexual behavior. Dev. Psychol. 52(5), 798–812 (2016)

Hamm, M.P., Newton, A.S., Chisholm, A., Shulhan, J., Milne, A., Sundar, P., Ennis, H., Scott, S.D., Hartling, L.: Prevalence and effect of cyberbullying on children and young people. JAMA Pediatrics 169(8), 770–777 (2015). http://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0944

Lenhart, A., Smith, A., Anderson, M., Duggan, M., Perrin, A.: Teens, technology and friendships, Pew Research Center (2015). http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/08/06/teens-technology-and-friendships/

Liu, D., Ainsworth, S.E., Baumeister, R.F.: A meta-analysis of social networking online and social capital. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 20(4), 369–391 (2016)

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., Ólafsson, K.: Risks and safety on the internet: the perspective of European children: full findings and policy implications from the EU Kids online survey of 9–16 year olds and their parents in 25 countries (2011). http://doi.org/2045-256X

Pelfrey, W.V, Weber, N.L.: Keyboard gangsters: analysis of incidence and correlates of cyberbullying in a large urban student population keyboard gangsters: analysis of incidence and correlates of cyberbullying in a large urban student population. Deviant Behav. 34(1), 68–84 (2013). http://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2012.707541

Putnam, R.D.: Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster, New York (2000)

Shapka, J.D., Maghsoudi, R.: Examining the validity and reliability of the cyber-aggression and cyber-victimization scale. Comput. Hum. Behav. 69, 10–17 (2017). http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.015

Tokunaga, R.S.: Following you home from school: a critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 26(3), 277–287 (2010). http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.014

Williams, D.: On and off the ’net : scales for social capital in an online era. J. Comput.-Mediated Commun. 11, 593–628 (2006). http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00029.x

Wisniewski, P., Jia, H., Xu, H., Rosson, M.B., Carroll, J.M.: ‘Preventative’ vs. ‘reactive:’ how parental mediation influences teens’ social media privacy behaviors. In: The Proceedings of the 2015 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW 2015), Vancouver, BC, Canada (2015)

Wisniewski, P., Xu, H., Rosson, M.B., Carroll, J. M.: Parents just don’t understand: why teens don't talk to parents about their online risk experiences. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (2017)

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation under grant CNS-1018302. Part of the work of Heng Xu was done while working at the U.S. National Science Foundation. Any opinion, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Sam, J., Wisniewski, P., Xu, H., Rosson, M.B., Carroll, J.M. (2017). How Are Social Capital and Parental Mediation Associated with Cyberbullying and Cybervictimization Among Youth in the United States?. In: Stephanidis, C. (eds) HCI International 2017 – Posters' Extended Abstracts. HCI 2017. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 714. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58753-0_90

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58753-0_90

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-58752-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-58753-0

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)