Abstract

It is said that nurses and care workers take different approaches when assisting the transfer of patients or care-receivers. For example, even on the same purpose, in case of the transfer assistance of a patient or care receiver from a bed to a wheelchair, they take different approaches. In our previous study, the transfer assistance motions of a care worker and a critical care nurse were observed when they were assisting a simulated care-receiver (hereinafter referred to as SCR) or simulated patient (hereinafter referred to as SP) to be transferred from a bed to a wheelchair using a slide board. Their motions were measured by the motion capture to comparatively analyze the differences. As a result, the both care worker and critical care nurse assisted the transfer the SCR and the SP using the same care-assistance device, but they took different approaches in each phase. The reason for the differences is attributed to their daily working circumstance or style how to assist care-receivers or patients. Care workers usually conduct the transfer assistance at elderly nursing facilities or individual homes of care-receivers, whereas nurses usually assist patients at hospitals. We arrived at the conclusion that environmental factors such as the difference in room sizes, room layouts, or whether the place where they are working is for medical treatment or daily life, are likely the main cause for the care workers and the nurses in each situation to create their own unique transfer assistance method [1]. As aforementioned, although care workers and nurses take different approaches, their purpose is the same, just to assist care-receivers or patients to be transferred safely. This is the most important thing what they have to bear in their mind. The purpose of this study is to clarify what kind of safety measures care workers or nurses take in their transfer assistance. We assigned one care worker and one nurse who is specializing in the critical care as test subjects and asked them to assist a simulated care-receiver (SCR) or a simulated patient (SP) to be transferred from a bed to a portable toilet. Their motions were measured and analyzed by motion capture. Transferring a care-receiver or a patient to a portable toilet is a daily task carried out in various assisted-motion environments, such as elderly care facilities, individual homes and hospital wards. One difference is that care workers mainly assist elderly care-receivers, while nurses, especially critical care nurses assist patients who just recovered from critical care, but both care workers and nurses are engaged in this task on the daily basis, we therefore chose this movement for the test situation.

Even though they may take different approaches, their main purpose is the same: assist the transfer safely. If we can specify the particular actions that are used to guarantee the patient’s safety, it will help us to connect how to safely assist in any working environment. Moreover, this study is not limited to care-receivers or patients’ safety, it is extended to concerns about the patient’s comfort. By measuring the jerk from the markers set on the SCR or SP’s head, we examined how and when the subjects were burdened, and consider what sort of movements are difficult for the patient. In order to cope with the upcoming super aging society, we hope the study will contribute to develop flexible, tailored made transfer assistance techniques that can be adapted to any working environments.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

In Japan, both roles that nursing and nursing care have been carried out by specialists referred to by the name of the certified care worker (kaigo fukushishi) and the nurse (kangoshi) respectively. According to Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the certified care worker is a nationally licensed practitioner who uses the appellation “certified care worker” to engage in the business of providing care for a person with physical disabilities or mental disorder and intellectual disabilities that make it difficult to lead a normal life, and to provide instructions on caregiving to the person and the person’s caregiver based on Certified Social Worker and Certified Care Worker Act (Act No. 30 of 1987) [2]. On the other hand, the nurse refers to a person under licensure from the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare to pro-vide medical treatment or assist in medical care for injured and ill persons or puerperal women, as a profession, according to the Article 5 of Act on Public Health Nurses, Midwives, and Nurses (Act No. 203 on July 30, 1948) [3]. Thus the difference is clearly stated in the legal language.

In our previous study, we evaluated the difference between care workers and nurses on their specialties, work contents, or what they have to observe on the legal basis [4]. In this study, we focus on the care assistance movements of a care worker and a critical care nurse when they support a care-receiver or a patient.

In the previous study, the transfer assistance motions were comparatively analyzed between the care worker and the critical care nurse by a motion analysis system. We examined the transfer of the care-receiver or patient from a bed to a wheelchair using slide board. It was found that they took different approaches in each phase, and the reason for the difference was attributed to their regular working environment. On the one hand, care workers usually conduct the transfer assistance at elderly nursing facilities or care-receivers’ homes, whereas nurses usually assist patients at hospitals. Due to the difference in room sizes and room layouts, among other environmental causes, we believe that they are naturally drawn to differing methods of assistance. When comparing the motions taken by the care worker and the critical care nurse, the most notable difference is that the care worker tended to take the postures to bear the physical burden on his lower back, while the nurse did not. Nurses are usually taught to assist patients based on the body mechanics theory as a foundational part of their education. The body mechanics principle is to apply the kinetics theory onto a human body and help to achieve the task safer and more efficiently. The technique based on the body mechanics shows effective human motions and movements related to postures and holding postures. It is considered to reduce physical burden of care workers and nurses and is incorporated widely in the field of nursing and elderly care facilities [5]. Therefore, when nurses are engaged in transfer assistance, their particular approach is based on body mechanics theory. For securing the safety and comfort of patients, when a patient’s condition is beyond the range of a single nurse’s capacity, they usually ask others for help or use care assistance devices.

On the other hand, care workers are mostly required to support the transfer of care-receivers in such a limited environments. In some cases, care workers work alone with their care-receivers striving to maintain safety and comfort, even if that sometimes means they must use postures that put undue stress on their own bodies. This study is intended to comparatively analyze the movements involved in supporting a care-receiver or patient as they move to a portable toilet, as performed by a care worker and a nurse specializing in critical care, using a motion capture system. Transferring a care-receiver or a patient to a portable toilet is one of the daily tasks performed in a variety of environments, including elderly care facilities, individual homes and hospital wards. Since this assistance is applied not only to elderly care-receivers, but also to patients recovering from the critical care, and both care workers and nurses provide it on a daily basis. We chose this task as a test situation believing that is most suitable for comparison analysis.

We attempted to clarify the essential movements for maintaining the safety and comfort of care-receivers and patients through comparative analysis of the motions performed by the care worker and the critical care nurse. We hope that the outcome of this study will contribute to developing flexible, tailored made transfer assistance techniques that can be adapted to any working environments. Furthermore, by measuring the jerk of the head top movements of the care-receiver or patient, we attempted to verify how and when undue physical stress was imposed on the care-receiver or patient during transfer. A sense that humans perceive changes in exercise, jerk is higher than the acceleration. In recent years it has been used for research on the measurement of movement of nursing care [6].

Care workers experiencing lower back pain has spurred the ongoing problem of care worker shortages. By taking full advantage of body mechanics theory, they can not only protect their own bodies, but also ensure the safety and comfort of care-receivers. Currently in nursing, “body mechanics theory” is the standard, however; we may have to reconsider if the safety and comfort of care-receivers and patients are completed secured under this practice. Very few studies in nursing research focus on patients’ discomfortability, and quantify human discomfort using numerical values. In this study, we aimed to verify what kind of actions help to secure the safety and comfort of care-receivers and patients by making use of these methods.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

In this study, we designated one skilled care worker and one nurse, specializing in critical care, as test subjects. The care worker has 23-year working experience, stands at 160 cm in height, 69 kg in weight. The nurse has over 20-year working experience at a hospital (but no working experience at elderly care facilities), stands at 164 cm in height, 52 kg in weight, and 48 years of age. One simulated care-receivers (SCR) is assigned for the care worker, and one simulated patient (SP) is for the nurse, respectively. Both the care worker and the critical care nurse assisted the SCR or SP from a bed to a portable toilet. At the beginning of the study, both the SCR and SP were asked to take a sitting posture on the bed. During the test, the both groups were asked to repeat the same transfer assistance motions several times, and their motions was recorded and analyzed by the motion capture system.

2.2 Recording Procedure

The transfer assistance motions carried out by the care worker and the critical care nurse were recorded by digital video camera. Simultaneously, coordinates captured by each marker were measured by the optical motion capture system MAC3D SYSTEM (Motion Analysis Co., Ltd.). The sampling frequency was set at 120 Hz for the care worker, 60 Hz for the nurse. Since the sampling frequency were different, we took the footage from every other frame of the care worker, and matched each frame to the footage of the nurse for equal comparison. The infrared reflective markers were attached 26 locations on the both care worker and the nurse, and 16 locations for the SCR, and 20 locations for the SP. In the coordinate system, the movement in the vertical direction (left-right) was set as the X-axis, the front-back direction was set as the Y-axis, and the up-down direction was set as the Z-axis. Focusing on the jerk at the moment just before and after the SCR and SP were seated on the portable toilet, the sitting condition was visually judged based the footage of the digital video camera and three-dimensional data.

3 Results and Discussion

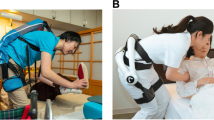

There was a difference in the time required for completing a series of transfer assistance action between the care worker and the critical care nurse. After making contact with the patient, the nurse took 8.484 s before transitioning to support the SP in standing up, whereas the care worker only took 3.191 s (Table 1). Because the nurse took more time to adjust the SP’s position on the bed before moving, the SP was easily helped to stand up from the bed. First, the nurse assisted the weight shift of the SP on the bed in the right-left direction while supporting the buttock, in order to reduce the surface contact between the SP and the bed, making standing up easier through a shallower sitting position (Fig. 1). Similar actions taken by the care worker were not observed. Moving the SP left and right reduces the physical stress on the nurse when standing-up, but it might impose some physical stress on the SP from rocking on the bed. Moreover, reducing the contact surface of the SP on the bed makes it easier for the nurse to move him toward the edge, but conversely, less surface contact makes the SP unstable, and in combination with rocking the patient back and forth, these methods could actually increase the danger of an accident from falling over in bed or even falling off of the bed.

After the nurse supported the SP to stand up completely, she took only 2.0 s for changing the direction of the SP’s body and guiding him to be positioned in front of the portable toilet, while the care worker spent 7.666 s for this phase. The care worker spent time explaining the upcoming movements to the SCR. Not merely giving a verbal explanation, but touching the SCR’s body part to be moved, this helped in shifting smoothly to the next movement (Fig. 2). This sort of explanation is thought to be valuable for not only securing the safety and comfort of care-receivers and patients, but also for preventing the occurrence of an accident caused by unexpected movements.

The common movements observed in both the care worker and the critical care nurse was securing a wide area for their base of support. Both the care worker and nurse kept their stance wider in the front-back direction, and stepped in between the SCR’ or the SP’s legs (Figs. 3 and 4). While keeping a wider base of support with this posture, they kept their knees engaged and their gravity center lower for securing the stability. This posture enables a smooth transfer for both who provide and received assistance [7]. Moreover, both the care worker and the nurse set their leg behind them without disturbing the course of motion. Both the care worker and the nurse faced toward the direction of motion to make sure the course was safe and clear of obstruction (Figs. 5 and 6), just as when parking a car. Both the care worker and the nurse kept a close distance to the SCR or the SP, enabling an efficient transfer. The above can perhaps be considered techniques for maintaining safety when assisting a transfer.

As the next step, the jerk was measured and comparatively analyzed through the markers attached on the top of the SCR’ and the SP’s heads, for quantifying the physical stress imposed on them as they were seated on the portable toilet. The data was collected from 30 frames (0.483 s) before the SCR or the SP was seated on the portable toilet until the moment the care worker or nurse lifted their hand after making sure the patient was completely seated. When comparing the footage, it was evident that the care worker and the nurse took the different approaches. The care worker supported the SCR’s upper body with her own and pulled her left leg further backward as his body leaning on her. Then, while maintaining support of the SCR’s upper body and without tilting her own upper body forward, assisted the SCR to a completely seated position on the portable toilet. After checking that the SCR was fully seated, she shifted her upper body weight toward the SCR, so that they could sit up straight, and then the care worker brought her hands away. The nurse supported the SP on the both sides and helped him to stand straight. Then, she shifted her weight toward the SP and lowered her gravity center by bending her knees, and had the SP sit back on the portable toilet by slightly pressing down the SP’s body.

Although the care worker and the nurse took the different approaches, both of them provided the care assistance considering the physical stress on care-receivers and patients as well as on themselves through weight shifting in accordance with body mechanics theory. Regarding the objective to maintain the safety of care-receivers and patients, if you compare Figs. 7 and 8, there is a relative difference in the largeness of the base of support. The care worker secured a wider base of support, so her approach is perhaps safer. They also supported the SCR’s upper body with her upper body. This posture enables the SCR to sit on the portable toilet by just bending their knees. Whereas the nurse supported the both sides of the SP and made the SP walk backward when approaching the portable toilet, these motions increase the possibility of the SP falling down or experiencing discomfort when walking backward and not being able to see where they are going. This suggest that the care worker’s approach is safer, more comfortable and effective at preventing accidents.

In order to verify how much physical stress was imposed on the SCR and the SP during the movements described above, the head motion jerk analysis results are as shown in Figs. 9 and 10. The head movements of the care worker and the nurse are shown in the Figs. 11 and 12, along with those of their respective SCR and SP. When we compared the footage, it was clear that the nurse’s movements were just to have the standing SP seated on the portable toilet. Therefore, the SP’s head moved along the path shown in Fig. 12. While the care worker supported the SCR’s upper body with her own, and after the SCR completely seated, the care worker shifted her weight toward the SCR, helping him sit upright. The SCR’s head moved along the path shown in Fig. 11. The differences in the paths of motion between the SCR and the SP is, as expressed earlier, indicative of their comfort.

When comparing the velocity (Figs. 13 and 14) and acceleration (Figs. 15 and 16) of the SCR’ and the SP’s head movements and jerk (Figs. 9 and 10), the SP’s head was swaying a lot around 0.5 s after the sitting action started, however, hardly any sudden movements were observed in the SCR’s entirely gentle trajectory.

When the nurse supported the SP to sit on the portable toilet, the nurse slightly pressed him down on the portable toilet. As his head movement track shows, the SP’s head swayed considerably from the recoil of being seated suddenly. As stated earlier, when the care worker helped the SCR to sit, she supported the SCR’s weight so he could sit gently by just bending their knees, so there was no recoil from being seated. The care worker took more time to finish seating the SCR, but thereby encountered less physical stress. It is perhaps the case that these differences come from their working background. While care workers usually focus on improving the remaining functions of care-receivers, critical care nurses focus on taking action as quickly as possible. Since it is generally the case that critical care nurses support patients recovered enough from critical care to use portable toilets, their focus is shifted toward completing excretion as quickly as possible, rather than towards minimizing physical stresses on the patient’s body. Even so, unnecessarily moving the patient’s head so much may cause instability in blood pressure and, especially since the patient is just recovered from the critical care, might solicit undue physical stress. It is important to pursue movements that minimize physical stresses on the patient from unnecessary movements, rather than focusing on reducing the time taken for a given movement.

When checking how care workers and nurses are educated to attain the proper actions required for safe transfer assistance of care-receivers and patients, they are educated mostly by the body mechanics theory that is devised to protect care workers and nurses. Even the movements of the critical care nurse seemed to be somewhat burdensome on the SP, even though their actions followed body mechanics principles. Nurses are also educated the torque principle how to move patients with less burden imposed on nurses, but through this study, we would like to return their awareness to the fact that the most important thing in transfer assistance is not to impose physical stress on patients or care-receivers. Although body mechanics principles aim to achieve both stability and efficiency, the result of this study suggests that the excessive reliance on body mechanics theory may increase the possibility of imposing physical stresses on patients or care-receivers.

4 Conclusion

This study, conducted on the premise that care workers and nurses take the different approaches in transfer assistance, attempted to verify the common elements of their movements in order to ensure the safety of their care recipients. Among the daily tasks that both care workers and nurses are engaged in, we focused on the transfer assistance motions from the bed to the portable toilet. The outcomes were evaluated in the two phases, the safety of the care-receiving side, and that of the care-providing side. In order to secure the safety of care-receivers and patients, care workers and nurses must provide stable transfer assistance, according to body mechanics theory, maintaining as wide a base of support as possible is important for stability of posture. Moreover, for securing the safety of care-providing side, body mechanics principles recommend that care-providers use weight shifting techniques when they are moving patients, being sure not to take unreasonable postures. These two outcomes have been already reported in other preceding studies, so they are not newly discovered knowledge. However, our findings throws a stone to the body mechanics supremacy myths that nursery personnel are currently relying on. By quantifying the physical burden imposed on the SCR and SP in this study, it was verified that the approach that body mechanics principles stipulate still impose physical stresses on the care-receiving side. Therefore, in further study, we aim to pursue the most ideal motions which will imposed the least physical stress on the both care-receiving and care-providing sides, while prioritizing the safety and comfort of the care-receiving side.

References

Kitajima, Y., Takai, Y., Yamashiro, K., Ogura, Y., Goto, A.: Comparative analysis of wheelchair transfer movements between nurse and care worker. In: Duffy, V.G. (ed.) DHM 2017, Part I. LNCS, vol. 10286, pp. 281–294. Springer, Cham (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58463-8_24

A website of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Outline of Certified Care Worker. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/kouseiroudoushou/shikaku_shiken/kaigohukushishi/. Accessed 22 Feb 2018. (in Japanese)

Act on Public Health Nurses, Midwives and Nurses: Article 5 (Act No. 203 on July 30, 1948) final revision, Act No. 83 on June 25, 2014. (in Japanese)

Kitajima, Y.: op.cit., pp. 281–294

Ogawa, K.: Assisting Nursing and Care: Work Posture and Movement, Learning Body Mechanics Through Illustration, pp. 53–54. Tokyo Denki University Press, Tokyo (2010). (in Japanese)

Koshino, Y., Ohno, Y., Hashimoto, M., Yoshida, M.: Evaluation parameters for care-giving motions. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 19(4), 299–306 (2007)

Kubota, S.: The Way to Improve the Living Environment Using Assistive Devices, pp. 50–55. Japanese Nursing Association Publishing Company, Tokyo (2017). (in Japanese)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this paper

Cite this paper

Kitajima, Y., Ikuhisa, K., Sirisuwan, P., Goto, A., Hamada, H. (2018). Increasing Safety for Assisted Motion During Caregiving. In: Duffy, V. (eds) Digital Human Modeling. Applications in Health, Safety, Ergonomics, and Risk Management. DHM 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 10917. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91397-1_34

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91397-1_34

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-91396-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-91397-1

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)