Abstract

The paper presents a computational framework for assessing quantitatively the detection capability of structural health monitoring (SHM) systems for flat plates. The detection capability is quantified using the probability of detection (POD) metric, developed within the area of nondestructive testing, which accounts for the variability of the uncertain system parameters and describes the detection accuracy using confidence bounds. SHM provides the capability of continuously monitoring the structural integrity using multiple sensors placed sensibly on the structure. It is important that the SHM can reliably and accurately detect damage when it occurs. The proposed computational framework models the structural behavior of flat plate using a spring-mass system with a lumped mass at each sensor location. The quantity of interest is the degree of damage of the plate, which is defined in this work as the difference in the strain field of a damaged plate with respect to the strain field of the healthy plate. The computational framework determines the POD based on the degree of damage of the plate for a given loading condition. The proposed approach is demonstrated on a numerical example of a flat plate with two sides fixed and a load acting normal to the surface. The POD is estimated for two uncertain parameters, the plate thickness and the modulus of elasticity of the material, and a damage located in one spot of the plate. The results show that the POD is close to zero for small loads, but increases quickly with increasing loads.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Probability of detection

- Nondestructive testing

- Structural health monitoring

- Model-assisted probability of detection

1 Introduction

Structural health monitoring (SHM) is used for the diagnosis and localization of damage existing in large-scale infrastructures (Laflamme et al. 2010, 2013). The increased utilization and insufficient maintenance of these infrastructures usually lead to high risks associated with their failures (Karbhhari 2009; Harms et al. 2010). Due to the expensive costs on repairs, timely inspection and maintenance are essential in improving health and ensuring safety of civil infrastructures (Brownjohn 2007), in turn to lengthen the sustainability.

Probability of detection (POD) (Sarkar et al. 1998) was developed to provide a quantitative assessment of the detection capability of nondestructive testing (NDT) systems (Blitz and Simpson 1996; Mix 2005). POD can be used for various purposes, for example, it can be used to demonstrate compliance with standard requirements for inspection qualification, such as “90% POD with 95% confidence”. It can also be used as input to probabilistic safety assessment (Spitzer et al. 2004; Chapman and Dimitrijevic 1999) and risk-based inspection (RBI) (Zhang et al. 2017; DET NORSKE VERITAS 2009). Because of these wide applications, POD is selected as an important metric in many industrial areas to detect defects or flaws, such as cracks inside parts or structures during manufacturing or for products in service. Traditional POD determination relies on experimental information (Generazio 2008; Bozorgnia et al. 2014). However, experiments can be time-consuming and expensive.

To reduce the experimental information needed for determining the POD, model-assisted probability of detection (MAPOD) methods have been developed (Thompson et al. 2009). MAPOD has been successfully applied to various NDT systems and modalities, such as eddy current simulations (Aldrin, et al. 2009), ultrasonic testing simulations (Smith et al. 2007), and SHM models (Aldrin et al. 2010, 2011). Due to the economic benefits of MAPOD in the SHM area, several approaches have been developed, such as the uniformed approach (Thompson 2008), advanced numerical simulations (Buethe et al. 2016; Aldrin et al. 2016; Lindgren et al. 2009), and have applied those on guided wave models (Jarmer and Kessler 2015; Memmolo et al. 2016).

In this paper, a MAPOD framework for SHM of flat plates is proposed. The approach determines the POD of damage of flat plates based on the loading and the degree of damage, which depends on the change in strain field of the damaged plate relative to the healthy one. The structural behavior is modeled with a simple spring-mass system to estimate the strain field. To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed framework, a flat plate with fixed ends and a normal load, as well as one damaged location is investigated. The uncertain parameters used in the study are plate thickness and the material modulus of elasticity. The results show that the framework can determine the POD as a function of the load and the degree of damage.

This paper is organized as follows. Next section describes the SHM structural model. Section 3 outlines the MAPOD framework used in this work. Section 4 presents results of a numerical example on the plate model. The paper ends with conclusion and plans of future work.

2 Structural Health Monitoring Model

SHM techniques use arrays of large-area electronics measuring strain to detect local faults. In Downey et al. (2017), a fully integrated dense sensor network (DSN) for the real-time SHM of wind turbine blades was proposed and experimentally validated on a prototype skin. The sensor, called soft elastomeric capacitor (SEC), is customizable in shape and size. The SEC’s unique attribute is its capability to measure additive in-plane strain. It follows that the signal needs to be decomposed into orthogonal directions in order to obtained unidirectional strain maps. The SEC based sensing skin is illustrated in Fig. 1, with the sketch Fig. 1a showing an individual SEC, and Fig. 1b showing the fully integrated DSN system.

Conceptual layout of a fully integrated SEC-based sensing skin for a wind turbine blade: (a) SEC with connectors and annotated axis; (b) deployment inside a wind turbine blade (Downey et al. 2017).

Inspired by the completed experimental work and SEC, a simulation model, developed as a matrix of discrete mass and stiffness elements, was constructed linking the strain to exist condition of the structures. A spring-mass system is used to represent the system being monitored, with a lumped mass at each sensor location. This model is based on the stiffness relationship between force vector F and measured displacement vector U. The additive strain is related to displacement by a transformation matrix D. Then, a static strain error function was defined to find the stiffness K by taking the difference between the predicted additive strain and field additive strain measurements.

Mindlin plate theory is used in this work to implement the plate model. In particular, the plate is divided by rectangular elements with SEC in the center for computational efficiency. On each element, the displacements in each node parallel to the undeformed middle plane, u and v, as a distance z from the centroidal axis can be expressed by

where \( \theta_{x} \) and \( \theta_{y} \) are the rotations of the normal to the middle plane with respect to axes y and x, respectively as illustrated in Fig. 2.

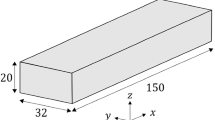

In this work, a fixed-ends plate is tested under a SHM system, containing 40 sensors, as shown in Fig. 3. Red regions represent the boundaries, which are fixed, so they are not considered in calculation. Cells containing blue numbers have sensors set up at centers, and strain field within the same cell is assumed to be uniform. Black numbers are computational nodes, where the calculation of strain is made.

The red circle at node #33 shows the location where the load is applied, pointing normal to the plate. The green cell, #30, will be used to add artificial damage at its center. Contours of the deflection field contours for a healthy plate are shown in Fig. 4.

3 MAPOD Framework

POD is essentially the quantification of inspection capability starting from the distributions of variability, and describes its accuracy with confidence bounds, also known as uncertain bounds. In many cases, the final product of a POD curve is the flaw size, a, for which there is a 90% probability of detection. This flaw size is denoted a 90 . The 95% upper confidence bound on a 90 is denoted as a 90/95 . The POD is typically determined through experiments which are both time-consuming and costly. This motivated the development of the MAPOD methods with the aim for reducing the number of experimental sample points by introducing insights physics-based simulations (Thompson et al. 2009).

The main elements of the proposed MAPOD framework is shown in Fig. 5. The process starts by defining the random inputs with specific statistical distributions (Fig. 5a). Next, the random inputs are propagated through the simulation model (Fig. 5b). For this step of the process, we use latin hypercube sampling (LHS) (Haddad 2013) to obtain identically independent samples from the input parameter distributions.

In this work, the simulation model is calculated using an analytical model (described in Sect. 2), to obtain the quantity of interest (Fig. 5c). In this work, the quantity of interest is the sum of the difference between current strain field and mean of healthy-plate strain field, in other words we are interested in Σ(S − μS*) where S is the current strain field and is the mean of the healthy plate strain field.

The stiffness and strain within each cell are assumed to be the same in the structural model. Therefore, to describe the damage of the cells, we introduce a reduction parameter, α, ranging between 0 and 1. If the reduction parameter is equal to 1 there is no damage, while a value of 0 indicates total damage. We also introduce a parameter representing the degree of damage as γ = 1 – α (which ranges between 0 and 1). Values close to 1 indicate high degree of damage, and values close to 0 indicate low degree of damage.

The next step in the MAPOD process is to construct the so-called “\( \hat{a} \) vs. \( a \)” plot (Fig. 5d) by drawing from the samples obtained in the last step and using linear regression to plot the quantity of interest (Σ(S − μS*)) versus the degree of damage (γ). With this information, the POD at each degree of damage is determined and the POD curves are generated (Fig. 5e).

4 Results

In this study, two random input parameters are considered, the thickness of the plate and the modulus of elasticity. The thickness distribution is assumed to have an uniform distribution of U(1.3 mm, 1.35 mm) and the modulus of elasticity is assumed to have a Gaussian distribution of N(7e4, 1e3). The distributions are shown in Fig. 6. The distributions are sampled one hundred times using latin hypercube sampling (LHS) (see Fig. 7). The LHS samples are propagated through the structural model with a force of F = 1 N without any damage. The mean strain field of those runs, μS*, is shown Fig. 8. This term is used as a reference vector, and POD curves can be generated through comparing the sum of the difference between this mean strain field and current strain field with detection threshold of system.

To determine the POD of the SHM system the following computational experiments are performed using the proposed MAPOD framework (Fig. 5). An artificial damage is introduced by parametrically varying the degree of damage parameter at cell number 30 (see Fig. 3), γ30, with the values of 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, and 0.9. In each case, we take 1,000 LHS samples and propagate them through structural model to obtain the output strain fields. From those results, we take the sum of the difference between each of those strain fields and the mean strain field of the healthy plate. With the “\( \hat{a} \) vs. \( a \)” plots generated, we set the detection threshold as 0.85 and determine the POD curves. The process is repeated for loads, F, ranging from low to medium to high. In this case, we use values of F of 0.1 N, 1 N, and 4 N.

The results of the MAPOD analysis giving the POD curves for the SHM system as a function of the load F and the degree of damage γ are presented in Figs. 9, 10 and 11. It can be seen that for low loads, the POD is very low, and the POD increases as the load increases. In particular, for F = 0.1 N, the POD is close to zero even when the damage is large. For the higher loads, the SHM system is capable of detecting the damage. More specifically, for F = 1 N the 50% POD, a 50 , 90% POD, a 90 , and 90% POD with 95% confidence, a 90/95 , are 0.3078, 0.5581, and 0.5776, respectively, whereas for F = 4 N, we have those metrics at 0.0619, 0.1157, and 0.1199, respectively. Thus, we can see that the larger load, the smaller the damage is needed to be detected, which in turn means that the detection capability is improving with increasing loads.

5 Conclusion

A framework for model-assisted probability of detection of structural health monitoring (SHM) systems of flat plates is proposed. Provided information on the uncertainties within the system and the sensor responses, the probability of detecting damage can be determined. The framework provided a quantitative capability to assess the reliability of SHM systems for flat plates. This capability is important when designing the SHM system. For example, answering the question of where to place the sensors. Future work will consider more complex cases, such as systems with larger numbers of uncertain parameters and damage locations.

References

Aldrin, J., Annis, C., Sabbagh, H., Lindgren, E.: Best practices for evaluating the capability of nondestructive evaluation (NDE) and structural health monitoring (SHM) techniques for damage characterization. In: 42th Annual Review of Progress in Quantitative Nondestructive Evaluation, pp. 200002-1–200002-10 (2016)

Aldrin, J., Knopp, J., Lindgren, E., Jata, K.: Model-assisted probability of detection evaluation for eddy current inspection of fastener sites. In: Review of Quantitative Nondestructive Evaluation, vol. 28, pp. 1784–1791 (2009)

Aldrin, J., Medina, E., Lindgren, E., Buynak, C., Knopp, J.: Case studies for model-assisted probabilistic reliability assessment for structural health monitoring systems. In: Review of Progress in Nondestructive Evaluation, vol. 30, pp. 1589–1596 (2011)

Aldrin, J., Medina, E., Lindgren, E., Buynak, C., Steffes, G., Derriso, M.: Model-assisted probabilistic reliability assessment for structure health monitoring systems. In: Review of Quantitative Nondestructive Evaluation, vol. 29, pp. 1965–1972 (2010)

Anan: Risk based inspection of offshore topsides static mechanical equipment. Det Norske Veritas, April 2009

Blitz, J., Simpson, G.: Ultrasonic Methods of Non-destructive Testing. Chapman & Hall, London (1996)

Bozorgnia, N., Schwetz, T.: What is the probability that direct detection experiments have observed dark matter. ArXiv ePrint arXiv.org/1410.6160 (2014)

Brownjohn, J.: Structural health monitoring of civil infrastructure. Philos. Trans. Roy. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 365(1851), 589–622 (2007)

Buethe, I., Dominguez, N., Jung, H., Fritzen, C.-P., Ségur, D., Reverdy, F.: Path-based MAPOD using numerical simulations. In: Wölcken, P.C., Papadopoulos, M. (eds.) Smart Intelligent Aircraft Structures (SARISTU), pp. 631–642. Springer, Cham (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22413-8_29

Chapman, J., Dimitrijevic, V.: Challenges in using a probabilistic safety assessment in a risk informed process (illustrated using risk informed inservice inspection). Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 63, 251–255 (1999)

Downey, A., Laflamme, S., Ubertini, F.: Experimental wind tunnel study of a smart sensing skin for condition evaluation of a wind turbine blade. Smart Mater. Struct. 26, 125005 (2017)

Generazio, E.: Directed design of experiments for validating probability of detection capability of NDE systems (DOEPOD). In: Review of Quantitative Nondestructive Evaluation, vol. 27 (2008)

Haddad, R.E., Fakhereddine, R., Lécot, C., Venkiteswaran, G.: Extended latin hypercube sampling for integration and simulation. In: Dick, J., Kuo, F., Peters, G., Sloan, I. (eds.) Monte Carlo and Quasi-Monte Carlo Methods 2012. Springer Proceedings in Mathematics and Statistics, vol. 65, pp. 317–330. Springer, Heidelberg (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41095-6_13

Harms, T., Sedigh, S., Bastinaini, F.: Structural health monitoring of bridges using wireless sensor network. IEEE Instru. Meas. Mag. 13(6), 14–18 (2010)

Jarmer, G., Kessler, S.: Probability of detection assessment of a guided wave structural health monitoring system. In: Structural Health Monitoring (2015)

Kabhari, V.M.: Design Principles for Civil Structures. Encyclopedia of Structural Health Monitoring, pp. 1467–1476. Wiley, Hoboken (2009)

Laflamme, S., Kollosche, M., Connor, J., Kofod, G.: Soft capacitive sensor for structural health monitoring of large-scale systems. J. Struct. Control 19, 1–21 (2010)

Laflamme, S., Kollosche, M., Conor, J., Kofod, G.: Robust flexible capacitive surface sensor for structural health monitoring applications. J. Eng. Mech. 139(7), 879–885 (2013)

Lindgren, E., Buynak, C., Aldrin, J., Medina, E., Derriso, M.: Model-assisted methods for validation of structural health monitoring systems. In: 7th International Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring, Stanford, CA (2009)

Memmolo, V., Ricci, F., Maio, L., Monaco, E.: Model-assisted probability of detection for a guided-waves based on SHM technique. In: SPIE Smart Structures and Materials and Nondestructive Evaluation and Health Monitoring, vol. 9805, pp. 980504-1–980504-12, April 2016

Mix, P.: Introduction to Nondestructive Testing. Wiley, Hoboken (2005)

Sarkar, P., Meeker, W., Thompson, R., Gray, T., Junker, W.: Probability of detection modeling for ultrasonic testing. In: Thompson, D.O., Chimenti, D.E. (eds.) Review of Progress in Quantitative Nondestructive Evaluation, vol. 17, pp. 2045–2046. Springer, Boston (1998). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-5339-7_265

Smith, K., Thompson, B., Meeker, B., Gray, T., Brasche, L.: Model-assisted probability of detection validation for immersion ultrasonic application. In: Review of Quantitative Nondestructive Evaluation, vol. 26, pp. 1816–1822 (2007)

Spitzer, C., Schmocker, U., Dang, V.: Probability safety assessment and management. In: International Conference on Probabilistic Safety Assessment, Berlin, Germany (2004)

Thompson, R.: A unified approach to the model-assisted determination of probability of detection. In: Review of Quantitative Nondestructive Evaluation, vol. 27, pp. 1685–1692 (2008)

Thompson, R., Brasche, L., Forsyth, D., Lindgren, E., Swindell, P.: Recent advances in model-assisted probability of detection. In: 4th European-American Workshop on Reliability of NDE, Berlin, Germany, 24–26 June 2009

Zhang, M., Liang, W., Qiu, Z., Liu, Y.: Application of risk-based inspection method for gas compressor station. In: 12th International Conference on Damage Assessment of Structures, Series, vol. 842 (2017)

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Center for Nondestructive Evaluation Industry/University Cooperative Research Program at Iowa State University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this paper

Cite this paper

Du, X., Yan, J., Laflamme, S., Leifsson, L., Tesfahunegn, Y., Koziel, S. (2018). Model-Assisted Probability of Detection for Structural Health Monitoring of Flat Plates. In: Shi, Y., et al. Computational Science – ICCS 2018. ICCS 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 10861. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93701-4_49

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93701-4_49

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-93700-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-93701-4

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)