Abstract

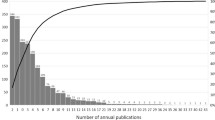

One of the basic dependent variables in the sociology of science is the rate at which scientific knowledge advances. Sociologists of science have in the past assumed that the rate of scientific advance was a function of the number of talented people entering science. This assumption was challenged by Derek Price who argued that as the number of scientists increased the number of “high quality” scientists would increase at a slower rate. This paper reports the results of an empirical study of changes in the size of academic physics in the U. S. between 1963 and 1975. In each year we count the number of new Assistant Professors appointed in Ph. D.-granting departments. During the early 1960s there was a sharp increase in the size of entering cohorts followed by a sharp decline. A citation analysis indicates that the proportion of each cohort publishing work which was cited at least once in the first three years after appointment was relatively constant. This leads to the conclusion that the number of scientists capable of contributing to the advance of scientific knowledge through their published research is a linear function of the total number of people entering science.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

D. J. de SOLLA PRICE,Little Science, Big Science, Columbia University Press, New York, 1963.

R. K. MERTON,Science, Technology and Society in Seventeenth-Century England, Harper and Row, New York, (First published 1938.), 1970.

G. BECKER, Pietism and Science: A Critique of Robert K. Merton's Hypothesis,American Journal of Sociology, 89 (1984) 1065–1090.

R. K. MERTON, The Fallacy of the Latest Word: The Case of ‘Pietism and Science’.American Journal of Sociology, 89 (1984) 1091–1121.

J. BEN-DAVID, A. ZLOCZOWER, Universities and Academic Systems in Modern Society,European Journal of Sociology, 3 (1962) 45–84.

J. R. COLE, S. COLE, The Ortega Hypothesis,Science, 178 (1972) 368–375.

G. S. MEYER, Academic Labor and the Development of Science, SUNY at Stony Brook. Unpublished Ph. D. dissertation, 1979.

L. GRODZINS, Physics Faculties, 1959–1975, Mimeo dated May, 1976.

D. BRENEMAN, Outlook and Opportunity for Graduate Education, Technical Report No. 3, National Board of Graduate Educatuion, Washington, D. C., 1975.

A. CARTTER,Ph. D.'s and the Academic Labor Market, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1976.

R. RADNER, L. S. MILLER,Demand and Supply in United States Higher Education, Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1975.

F. NARIN,Evaluative Bibliometrics, Computer Horizons, Inc. Cherry Hill, New Jersey, 1976.

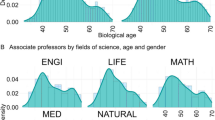

S. COLE, Age and Scientific Performance,American Journal of Sociology, 84 (1979) 958–77.

National Science Foundation,Science Indicators, Government Printing Office, Washington D. C., 1976.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Standard and Poor's Corporation

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cole, S., Meyer, G.S. Little science, big science revisited. Scientometrics 7, 443–458 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02017160

Received:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02017160