Abstract

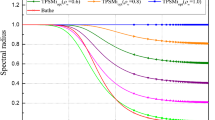

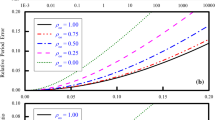

This paper presents a new semi-explicit dissipative model-dependent time integration algorithm for solving structural dynamics problems. Motivated by the superior properties of the composite time-stepping scheme, the proposed method is designed, so that it fully inherits the numerical characteristics of its parent algorithm, namely the Bathe method. The algorithm design procedure is carried out by assuming unknown integration parameters for the proposed method. Afterwards, by time discretization of an SDOF model equation, the unknown parameters can be obtained explicitly by solving nonlinear system of equations. Some numerical examples are analyzed by the presented technique and comparisons are also made with two other dissipative model-dependent time integration algorithms as well as the Bathe method. Results demonstrate that the suggested technique can effectively damp out the spurious oscillations of the high-frequency modes, while the other schemes exhibit significant overshoot in the calculated responses. Furthermore, it is also observed that numerical results of the presented method totally coincide with the parent algorithm. While the Bathe method subdivides each time increment into two sub-steps, the proposed algorithm is single-step, non-iterative and does not involve any time-step subdividing.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bathe K-J (2006) Finite element procedures. Prentice Hall, Pearson Education Inc.

Hughes TJ (1983) Analysis of transient algorithms with particular reference to stability behavior. In: Computational methods for transient analysis. North-Holland Comput Methods in Mech., Amsterdam, pp 67–155

Namadchi AH, Alamatian J (2016) Explicit dynamic analysis using dynamic relaxation method. Comput Struct 175:91–99

Dokainish M, Subbaraj K (1989) A survey of direct time-integration methods in computational structural dynamics—I. Explicit methods. Comput Struct 32(6):1371–1386

Subbaraj K, Dokainish M (1989) A survey of direct time-integration methods in computational structural dynamics—II. Implicit methods. Comput Struct 32(6):1387–1401

Bathe KJ, Wilson E (1972) Stability and accuracy analysis of direct integration methods. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 1(3):283–291

Kolay C, Ricles JM (2016) Assessment of explicit and semi-explicit classes of model-based algorithms for direct integration in structural dynamics. Int J Numer Methods Eng 107(1):49–73

Chang S-Y (2010) A new family of explicit methods for linear structural dynamics. Comput Struct 88(11–12):755–772

Chang S-Y (2002) Explicit pseudodynamic algorithm with unconditional stability. J Eng Mech 128(9):935–947

Namadchi AH, Fattahi F, Alamatian J (2017) Semiexplicit unconditionally stable time integration for dynamic analysis based on composite scheme. J Eng Mech 143(10):04017119

Chang SY (2014) A family of noniterative integration methods with desired numerical dissipation. Int J Numer Methods Eng 100(1):62–86

Chen C, Ricles JM (2008) Development of direct integration algorithms for structural dynamics using discrete control theory. J Eng Mech 134(8):676–683

Chung J, Hulbert G (1993) A time integration algorithm for structural dynamics with improved numerical dissipation: the generalized-α method. J Appl Mech 60(2):371–375

Bathe K-J, Noh G (2012) Insight into an implicit time integration scheme for structural dynamics. Comput Struct 98:1–6

Kolay C, Ricles JM (2014) Development of a family of unconditionally stable explicit direct integration algorithms with controllable numerical energy dissipation. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 43(9):1361–1380

Hilber HM, Hughes TJ, Taylor RL (1977) Improved numerical dissipation for time integration algorithms in structural dynamics. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 5(3):283–292

Chang S-Y (2015) Dissipative, noniterative integration algorithms with unconditional stability for mildly nonlinear structural dynamic problems. Nonlinear Dyn 79(2):1625–1649

Wood W, Bossak M, Zienkiewicz O (1980) An alpha modification of Newmark’s method. Int J Numer Methods Eng 15(10):1562–1566

Bathe K-J (2007) Conserving energy and momentum in nonlinear dynamics: a simple implicit time integration scheme. Comput Struct 85(7–8):437–445

Bathe K-J, Baig MMI (2005) On a composite implicit time integration procedure for nonlinear dynamics. Comput Struct 83(31–32):2513–2524

Liu T et al (2012) An efficient backward Euler time-integration method for nonlinear dynamic analysis of structures. Comput Struct 106:20–28

Noh G, Ham S, Bathe K-J (2013) Performance of an implicit time integration scheme in the analysis of wave propagations. Comput Struct 123:93–105

Wen W et al (2017) A comparative study of three composite implicit schemes on structural dynamic and wave propagation analysis. Comput Struct 190:126–149

Liang X, Mosalam KM, Günay S (2016) Direct integration algorithms for efficient nonlinear seismic response of reinforced concrete highway bridges. J Bridge Eng 21(7):04016041

Zhang J, Liu Y, Liu D (2017) Accuracy of a composite implicit time integration scheme for structural dynamics. Int J Numer Methods Eng 109(3):368–406

Hughes TJ (2012) The finite element method: linear static and dynamic finite element analysis. Courier Corporation, Chelmsford

Noh G, Bathe K-J (2019) The Bathe time integration method with controllable spectral radius: the ρ∞-Bathe method. Comput Struct 212:299–310

Noh G, Bathe K-J (2018) Further insights into an implicit time integration scheme for structural dynamics. Comput Struct 202:15–24

Huang C, Fu M (2018) A composite collocation method with low-period elongation for structural dynamics problems. Comput Struct 195:74–84

Wen W et al (2017) A novel sub-step composite implicit time integration scheme for structural dynamics. Comput Struct 182:176–186

Malakiyeh MM, Shojaee S, Javaran SH (2018) Development of a direct time integration method based on Bezier curve and 5th-order Bernstein basis function. Comput Struct 194:15–31

Kadapa C, Dettmer W, Perić D (2017) On the advantages of using the first-order generalised-alpha scheme for structural dynamic problems. Comput Struct 193:226–238

Shojaee S, Rostami S, Abbasi A (2015) An unconditionally stable implicit time integration algorithm: modified quartic B-spline method. Comput Struct 153:98–111

Crisfield MA (1997) Non-linear finite element analysis of solids and structures: advanced topics. Wiley, New York, p 508

Cook RD (2007) Concepts and applications of finite element analysis. Wiley, New York

Chang S-Y (2018) An unusual amplitude growth property and its remedy for structure-dependent integration methods. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 330:498–521

Koohestani K, Kaveh A (2010) Efficient buckling and free vibration analysis of cyclically repeated space truss structures. Finite Elem Anal Des 46(10):943–948

Bathe K-J, Bolourchi S (1980) A geometric and material nonlinear plate and shell element. Comput Struct 11(1–2):23–48

Namadchi AH, Alamatian J (2017) Dynamic relaxation method based on Lanczos algorithm. Int J Numer Methods Eng 112(10):1473–1492

Pica A, Wood R, Hinton E (1980) Finite element analysis of geometrically nonlinear plate behaviour using a Mindlin formulation. Comput Struct 11(3):203–215

Goudreau GL, Taylor RL (1973) Evaluation of numerical integration methods in elastodynamics. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 2(1):69–97

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Table 2 summarizes the necessary steps for conducting time integration through the MDED technique. In this table, N represents the numerator of the integration parameters in MDOF space. Moreover, \(\left[ {\mathbf{I}} \right]\) is the identity matrix of size q, where q is the number of degrees of freedom.

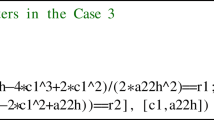

Appendix 3

The ‘N’ notation is an operator which returns the numerator of a rational function. Similarly, operator ‘D’ could be defined which give the denominator of a rational function. For instance, considering αi (integration parameter) as a rational function:

Thus

Regarding the generalization of this concept to MDOF systems (Matrix form), a simple example is introduced to clarify the matter. Let us suppose one wants to generalize αi for a system with three degrees of freedom. Since every mode of vibration has a unique natural frequency, there are three integration parameters (with different \(\varOmega\) and ζ). Thus, one could write

Here, subscripts 1, 2 and 3 represent the mode number. Equation (48) could be written, alternatively, in matrix form:

Owing to diagonality of (49), simple matrix decomposition can be performed as follows:

Or

However, Eq. (52) involves modal parameters and in practice, it should be transformed to standard finite-element coordinates. This can be done by employing the transformations introduced in this paper [Eqs. (32) and (33)]. For example, \(\left[ {N_{{\left( {{\mathbf{\bar{\rm A}}}_{i} } \right)}} } \right]\) could be written as

The above procedure could be performed for all of the integration parameters. Thus, they can be described only in terms of original system matrices and in the form of \(\left[ {\varvec{\Phi}} \right]^{T} \left( \ldots \right)\left[ {\varvec{\Phi}} \right]^{{ - {\text{T}}}}\).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Namadchi, A.H., Jandaghi, E. & Alamatian, J. A new model-dependent time integration scheme with effective numerical damping for dynamic analysis. Engineering with Computers 37, 2543–2558 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00366-020-00960-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00366-020-00960-w