Abstract

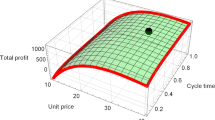

Both cash and credit sale are common. Considering the upsides and downsides of these two payment policies, in this paper, we study how a firm should choose between them. In particular, based on the relationship between demand and the inventory level, four strategies are considered for the case of credit sale: only selling to high-quality buyers (S1); selling to high-quality buyers when demand is high and selling to both low- and high-quality buyers otherwise (S2); selling to both when the demand is moderate and selling only to high-quality buyers otherwise (S3); and selling to both when demand is low and selling only to high-quality buyers otherwise (S4). What we find is that credit sale strictly dominates cash sale except when the expected profit from selling to low-quality buyers is less than the salvage value and the demand coefficient of variation is extremely high. Further, under credit sale, two counterintuitive observations are obtained if the demand coefficient of variation is small. The first is that the analysis reveals that the firm may not serve the low-quality buyers despite that doing so offers profits, i.e., S3 is the most preferable strategy for the firm. The second is that the firm may also serve the low-quality buyers despite incurring a loss by doing so, i.e., S4 is the most attractive strategy. In addition, we demonstrate that when the credit sale is employed, the firm’s optimal expected profit decreases both in the proportion of high-quality buyers in the market and in the low-quality buyers’ payment probability when the demand coefficient of variation is significantly small, which is quite different from our conjecture. All of these results provide some distinct insights into the question of what the firm’s best payment policy is and how credit should be extended when credit sale is used.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Notes

This is also achievable in reality. For example, Alibaba lists many requirements that buyers must meet when applying for credit, such as \(4+\) or \(12+\) months of trading history and having \(\pounds 10,000+\) in annual sales, and buyers also need to provide documentation to verify their integrity, such as the last 3-month bank account statements, an form IRS 4506T, and last year’s business tax return. Based on these documents, both the firm and the sales agent can accurately determine the quality of a buyer.

Note that the firm will always sell all its products to the high-quality buyers under all strategies when the number of high-quality buyers secured \(\mu X\) is greater than the inventory level Q. Therefore, hereafter, when we mention one strategy, only the action on the interval \(X\le \frac{Q}{\mu }\) will be described.

References

Babich V, Aydın G, Brunet PY et al (2012) Risk, financing and the optimal number of suppliers. In: Gurnani H, Mehrotra A, Ray S (eds) Supply chain disruptions. Theory and practice of managing risk. Springer, London, pp 195–240

Berger AN, Udell GF (2002) Small business credit availability and relationship lending: the importance of bank organisational structure. Econ J 112:F32–F53

Biais B, Gollier C (1997) Trade credit and credit rationing. Rev Financ Stud 10:903–937

Bougheas S, Mateut S, Mizen P (2009) Corporate trade credit and inventories: new evidence of a trade-off from accounts payable and receivable. J Bank Finance 33:300–307

Brennan MJ, Maksimovics V, Zechner J (1988) Vendor financing. J Finance 43:1127–1141

Burkart M, Ellingsen T (2004) In-kind finance: a theory of trade credit. Am Econ Rev 94:569–590

Buzacott JA, Zhang RQ (2004) Inventory management with asset-based financing. Manag Sci 50:1274–1292

Cai GG, Chen X, Xiao Z (2014) The roles of bank and trade credits: theoretical analysis and empirical evidence. Prod Oper Manag 23:583–598

Chao X, Chen J, Wang S (2008) Dynamic inventory management with cash flow constraints. Naval Res Logist 55:758–768

Chod J (2016) Inventory, risk shifting, and trade credit. Manag Sci (Forthcoming)

Chu LY, Lai G (2013) Salesforce contracting under demand censorship. Manuf Serv Oper Manag 15:320–334

Cunat V (2007) Trade credit: suppliers as debt collectors and insurance providers. Rev Financ Stud 20:491–527

Dada M, Hu Q (2008) Financing newsvendor inventory. Oper Res Lett 36:569–573

Daripa A, Nilsen JH (2005) Subsidizing inventory: a theory of trade credit and pre-payment. SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2342661

Emery GW (1987) An optimal financial response to variable demand. J Financ Quant Anal 22:209–225

Emery G, Nayar N (1998) Product quality and payment policy. Rev Quant Finance Account 10:269–284

Ferrando A, Mulier K (2013) Do firms use the trade credit channel to manage growth? J Bank Finance 37:3035–3046

Gupta D, Wang L (2009) A stochastic inventory model with trade credit. Manuf Serv Oper Manag 11:4–18

Iancu D, Trichakis N, Tsoukalas G et al (2014) Operationalizing financial covenants. Technical Report

Jain N (2001) Monitoring costs and trade credit. Quart Rev Econ Finance 41:89–110

Jing B, Chen X, Cai GG (2012) Equilibrium financing in a distribution channel with capital constraint. Prod Oper Manag 21:1090–1101

Kouvelis P, Zhao W (2011) The newsvendor problem and price-only contract when bankruptcy costs exist. Prod Oper Manag 20:921–936

Kouvelis P, Zhao W (2012) Financing the newsvendor: supplier versus bank, and the structure of optimal trade credit contracts. Oper Res 60:566–580

Lai G, Debo LG, Sycara K (2009) Sharing inventory risk in supply chain: the implication of financial constraint. Omega 37:811–825

Lee YW, Stowe JD (1993) Product risk, asymmetric information, and trade credit. J Financ Quant Anal 282:285–300

Li Y, Zhen X, Cai X (2014) Trade credit insurance, capital constraint, and the behavior of manufacturers and banks. Ann Oper Res 240:395–414

Long MS, Malitz IB, Ravid SA (1993) Trade credit, quality guarantees, and product marketability. Financ Manag 22:117–127

Luo W, Shang K (2014) Managing inventory for entrepreneurial firms with trade credit and payment defaults. SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2330951

Maksimovic V, Frank MZ (2005) Trade credit, collateral, and adverse selection. Unpublished working paper, University of Maryland. https://ssrn.com/abstract=87868; doi:10.2139/ssrn.87868

Mateut S, Bougheas S, Mizen P (2006) Trade credit, bank lending and monetary policy transmission. Eur Econ Rev 50:603–629

Petersen MA (2004) Information: hard and soft. Technical Report working paper, Northwestern University

Peura H, Yang, SA, Lai G (2015) Risk or margin: the role of trade credit in competition. SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2571493

Seifert D, Seifert RW, Protopappa-Sieke M (2013) A review of trade credit literature: opportunities for research in operations. Eur J Oper Res 231:245–256

Smith JK (1987) Trade credit and informational asymmetry. J Finance 42:863–872

Wilner BS (2000) The exploitation of relationships in financial distress: the case of trade credit. J Finance 55:153–178

Xu X, Birge JR (2004) Joint production and financing decisions: modeling and analysis. SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=652562

Yang SA, Birge JR (2011) Trade credit in supply chains: multiple creditors and priority rules. SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1840663

Yang SA, Birge JR (2013) How inventory is (should be) financed: trade credit in supply chains with demand uncertainty and costs of financial distress. SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1734682

Yang SA, Birge JR, Parker RP (2015) The supply chain effects of bankruptcy. Manag Sci 61:2320–2338

Zhou J (2009) Essays in interfaces of operations and finance in supply chains. Ph.D. thesis, University of Rochester

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 71771165, No. 71771166, No. 71471126 and No. 71301114.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Communicated by Y. Ni.

Appendix: proofs

Appendix: proofs

Proof to Theorem 1

In this case, it can be verified that the firm’s objective function is a quadratic function, with the second-order derivative being \(\frac{\partial ^2 \Pi _0}{\partial Q^2}=-\frac{p-s}{\mu \Delta }\le 0\). Hence, the optimal solution exists and it is \(Q_0^{*}=\frac{\mu \left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s) \right] }{p-s} \ge 0\) and the firm’s expected profit is \(\Pi _0^{*}=\frac{\mu \left[ \Delta (p-c)^2+2k(p-s)(p-c)\right] }{2(p-s)}\ge 0\). Further, we have

and

\(\square \)

Proof to Theorem 2

The firm’s objective function is a quadratic function, with the second-order derivative being \(\frac{\partial ^2 \Pi _3}{\partial Q^2}=-\frac{\mu (p\gamma -s)+p(1-\gamma )}{\mu \Delta }\le 0\). Hence, optimal solution exists only when \(\mu (p\gamma -s)+p(1-\gamma )\ge 0\). This is always true since if \(\mu (p\gamma -s)+p(1-\gamma )<0\), then \(s>\frac{(1+\mu \gamma -\gamma )p}{\mu }=p+\frac{(1-\mu )(1-\gamma )p}{\mu }{}_{\phantom {\frac{1}{1}}}\) can be derived, which is impossible. Hence, the optimal solution exists and it is \(Q_2^{*}=\frac{\mu \left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s) \right] }{\mu (p\gamma -s)+p(1-\gamma )} \ge 0{}_{\phantom {\frac{1}{1}}}\) and the firm’s expected profit is \(\Pi _2^{*}=\frac{\mu \Delta ^2(p-c)^2+2\mu \Delta k(p-s)(p-c)-k^2(1-\mu )^2(p\gamma -s)(1-\gamma )p}{2\Delta \left[ \mu (p\gamma -s)+p(1-\gamma )\right] }\). Further, we have

and

\(\square \)

Proof to Theorem 3

The firm’s objective function is a quadratic function, with the second-order derivative being \(\frac{\partial ^2 \Pi _3}{\partial Q^2}=\frac{(1-\mu )^2(p\gamma -s)-(p-s)}{\mu \Delta }\le 0\). Hence, the optimal solution exists and it is \(Q_3^{*}=\frac{\mu \left[ \Delta (c-p)+k(s-p)\right] }{(p\gamma -s)(1-\mu )^2-(p-s)} \ge 0\) and the firm’s expected profit is

Further, we have

and

\(\square \)

Proof to Theorem 4

In this case, the firm’s objective function is also a quadratic function, with the second-order derivative being \(\frac{\partial ^2 \Pi _4}{\partial Q^2}=\frac{\mu (1-\mu )(p\gamma -s)-(p-s)}{\mu \Delta }\le 0\). Hence, the optimal solution also exists and it is \(Q_4^{*}=\frac{\mu \left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s)\right] }{\mu (\mu -1) (p\gamma -s)+p-s}{}_{\phantom {\frac{1}{1}}} \ge 0\) and the firm’s expected profit is \(\Pi _4^{*}=\frac{\mu \Delta ^2(p-c)^2+2\mu \Delta k(p-s)(p-c)-k^2(p\gamma -s)(1-\mu )^2\left[ (p-s)+\mu p(1-\gamma )\right] }{2\Delta \left[ p-s-\mu (1-\mu )(p\gamma -s)\right] }\). Further, we have

and

\(\square \)

Proof to Proposition 1

From Theorems 1–4, we can see that the relationship between the expected profit from selling the products to the low-quality buyers and the unit salvage value are quite important.

-

If \(p\gamma -s>0\), then

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \displaystyle \Pi _{4}^{*}-\Pi _2^{*}=-\frac{\mu (1-\mu )^2(p\gamma -s) \left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s)\right] ^2}{2\Delta \left[ p-s-\mu (1-\mu )(p\gamma -s)\right] \left[ \mu (p\gamma -s)+p(1-\gamma )\right] } \le 0\\ \displaystyle \Pi _{3}^{*}-\Pi _1^{*}=\frac{\mu (1-\mu )^2(p\gamma -s) \left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s)\right] ^2}{2\Delta (p-s)\left[ p-s-(1-\mu )^2(p\gamma -s) \right] } \ge 0.\\ \end{array} \right. \end{aligned}$$(EC.4)Therefore, only S3 and S2 are possible and \(\Pi _{3}-\Pi _2\) matters, which is

$$\begin{aligned} \Pi _{3}^{*}-\Pi _2^{*}=\frac{(1-\mu )(p\gamma -s)\left\{ -\mu ^2\left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s)\right] ^2+k^2\left[ \mu (p\gamma -s)+p(1-\gamma )\right] \left[ p-s-(1-\mu )^2(p\gamma -s)\right] \right\} }{2\Delta \left[ (p-s)-(1-\mu )^2 (p\gamma -s)\right] \left[ \mu (p\gamma -s)+p(1-\gamma )\right] }. \end{aligned}$$(EC.5)That is, it depends on the sign of

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle B_1= & {} -\mu ^2\left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s)\right] ^2\nonumber \\&+\,k^2\left[ \mu (p\gamma -s)+p(1-\gamma )\right] \nonumber \\&\times \,\left[ p-s-(1-\mu )^2(p\gamma -s)\right] . \end{aligned}$$(EC.6)When \(B_1\ge 0\), then S3 is the best strategy; otherwise, strategy S2 is the best one. But no matter which one is the best, we always have

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle Q_{3}^{*}-Q_2^{*}= & {} \frac{\mu (1-\mu )(p\gamma -s)\left[ \mu \Delta (p-c)+\mu k(p-s)\right] }{\left[ (p\gamma -s)(1-\mu )^2-(p-s)\right] \left[ \mu (p\gamma -s)+p(1-\gamma )\right] }\nonumber \\\le & {} 0. \end{aligned}$$Further, the impacts of the parameters such as k, \(\Delta \), s, \(\mu \), and \(\gamma \) are given as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \displaystyle \frac{\partial B_1}{\partial k}=2\mu ^2\left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s)\right] (p-s)\\ \quad -2k\left[ \mu (p\gamma -s)+p(1-\gamma )\right] \left[ p-s-(1-\mu )^2(p\gamma -s)\right] \\ \displaystyle \frac{\partial B_1}{\partial \Delta }=2\mu ^2\left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s)\right] (p-c)\ge 0\\ \displaystyle \frac{\partial B_1}{\partial s}=-2\mu ^2\Delta k(p-c)+k^2\left\{ \mu (2-\mu )\right. \\ \quad \left[ p(1-\gamma )+\mu (p\gamma -s)\right] +\mu \left[ (1-2\mu )(p-s)\right. \\ \left. \left. \quad -(1-\mu )^2(p\gamma -s)\right] \right\} \\ \displaystyle \frac{\partial B_1}{\partial \mu }=2\mu \left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s)\right] ^2-k^2(p\gamma -s)\\ \quad \left\{ p-s-(1-\mu )^2(p\gamma -s)+2(1-\mu )\right. \\ \left. \quad \left[ \mu (p\gamma -s)+p(1-\gamma )\right] \right\} .\\ \displaystyle \frac{\partial B_1}{\partial \gamma }=k^2(1-\mu )p\left[ (3\mu -1-2\mu ^2)(p\gamma -s)\right. \\ \left. \quad +p-s+p(1-\mu )(1-\gamma )\right] .\\ \end{array} \right. \end{aligned}$$ -

If \(p\gamma -s<0\), then

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \displaystyle \Pi _{4}^{*}-\Pi _2^{*}=-\frac{\mu (1-\mu )^2(p\gamma -s)\left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s)\right] ^2}{2\Delta \left[ p-s-\mu (1-\mu )(p\gamma -s)\right] \left[ \mu (p\gamma -s)+p(1-\gamma )\right] } \ge 0\\ \displaystyle \Pi _{3}^{*}-\Pi _1^{*}=\frac{\mu (1-\mu )^2(p\gamma -s)\left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s)\right] ^2}{2\Delta (p-s)\left[ p-s-(1-\mu )^2(p\gamma -s)\right] } \le 0.\\ \end{array} \right. \end{aligned}$$(EC.7)Therefore, only S1 and S4 are possible and \(\Pi _{4}-\Pi _1\) matters, which is

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \Pi _{4}^{*}-\Pi _1^{*}=\frac{(1-\mu )(p\gamma -s)\left\{ \mu ^2\left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s)\right] ^2-k^2(p-s)\left[ p-s-\mu (1-\mu )(p\gamma -s)\right] \right\} }{2\Delta (p-s)\left[ p-s-\mu (1-\mu )(p\gamma -s)\right] }. \end{aligned}$$(EC.8)That is, it depends on the sign of

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle B_2= & {} \mu ^2\left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s)\right] ^2\nonumber \\&-k^2(p-s) \left[ p-s-\mu (1-\mu )(p\gamma -s)\right] .\nonumber \\ \end{aligned}$$(EC.9)When \(B_2\ge 0\), then S1 is the best one; otherwise, S1 is the best one. However, no matter which strategy is the best, we always have

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle Q_{4}^{*}-Q_1^{*}= & {} \frac{\mu (1-\mu )(p\gamma -s)\left[ \mu \Delta (p-c)+\mu k(p-s)\right] }{(p-s)\left[ p-s-\mu (1-\mu )(p\gamma -s)\right] }\nonumber \\\le & {} 0. \end{aligned}$$(EC.10)Further, we have:

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \displaystyle \frac{\partial B_2}{\partial k}=2\mu ^2\Delta (p-c)(p-s)-2k(p-s)(1-\mu )\\ \qquad \,\,\,\, \left[ p-s+\mu p(1-\gamma )\right] \\ \displaystyle \frac{\partial B_2}{\partial \Delta }=2\mu ^2\left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s)\right] (p-c)\ge 0\\ \displaystyle \frac{\partial B_2}{\partial s}=-2\mu ^2\Delta k(p-c)+k^2\left[ (2-\mu -\mu ^2)(p-s)\right. \\ \qquad \qquad \left. -\,\mu (1-\mu )(p\gamma -s)\right] \\ \displaystyle \frac{\partial B_2}{\partial \mu }=2\mu \left[ \Delta (p-c)+k(p-s)\right] ^2\\ \qquad \,\,\,\, -\,k^2(2\mu -1)(p-s)(p\gamma -s)\\ \displaystyle \frac{\partial B_2}{\partial \gamma }=\mu (1-\mu )pk^2(p-s)\ge 0.\\ \end{array} \right. \end{aligned}$$(EC.11)

\(\square \)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Lan, Y., Zhao, R. et al. The optimal payment policy for a firm: cash sale versus credit sale. Soft Comput 22, 5843–5860 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-017-2770-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-017-2770-9