Abstract

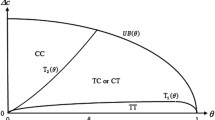

To maintain the competence, an increasing number of original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) outsource their production manufacturing to contract manufacturers (CMs). While the outsourcing strategy benefits the manufacturers greatly, it also brings huge risk derived from uncertain environment, which may directly affect the supply chain members’ competitive profits and then their leadership preferences in competition. To address this problem, this paper considers a model in which an OEM outsources its production partly to a competitive CM (CCM), who also sells her own products; moreover, they hold different risk attitudes toward the uncertain demand, characterized by the confidence level in the framework of uncertainty theory. Based on the framework, to explore the OEM’s and the CCM’s leadership preferences, we derive and compare the simultaneous game, the OEM-as-leader game and the CCM-as-leader game. We present an interesting insight that, with a high wholesale price, the leadership position is more attractive for a relatively risk-aversion OEM and a relatively risk-loving CCM, which demonstrates contrary effects of both one’s risk attitudes. Furthermore, we also find that both the OEM and the CCM would like to play the leadership when both the wholesale price and the outsourcing rate to the CCM is relatively low. However, in the case of a relatively high outsourcing rate and wholesale price, both parties would like to compromise to move last rather than sticking on moving first.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.References

Amir R, Stepanova A (2006) Second-mover advantage and price leadership in Bertrand duopoly. Games Econ Behav 55(1):1–20

Arrunada B, Vázquez X (2006) When your contract manufacturer becomes your competitor. Harv Bus Rev 84(9):135

Bárcena-Ruiz J (2007) Endogenous timing in a mixed duopoly: price competition. J Econ 91(3):263

Bhattacharyya R, Chatterjee A, Kar S (2010) Uncertainty theory based novel multi-objective optimization technique using embedding theorem with application to R&D project portfolio selection. Appl Math 1(3):189

Caputo M, Zirpoli F (2002) Supplier involvement in automotive component design: outsourcing strategies and supply chain management. Int J Technol Manag 23(1–3):129–159

Chen H, Wang X, Liu Z, Zhao R (2017) Impact of risk levels on optimal selling to heterogeneous retailers under dual uncertainties. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-017-0481-9

Chen Z, Lan Y, Zhao R (2016) Impacts of risk attitude and outside option on compensation contracts under different information structures. Fuzzy Optim Decis Mak. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10700-016-9263-7

Chen X (2014) Uncertain calculus and uncertain finance. UTLab, Beijing, p 2013

Chiu C, Choi T (2013) Supply chain risk analysis with mean-variance models: a technical review. Ann Oper Res 240(2):489–507

Gans N, Zhou Y (2007) Call-routing schemes for call-center outsourcing. Manuf Serv Oper Manag 9(1):33–50

Guo C, Gao J (2017) Optimal dealer pricing under transaction uncertainty. J Intell Manuf 3(28):657–665

Gao Y (2012) Uncertain models for single facility location problems on networks. Appl Math Model 36(6):2592–2599

Hazen B, Boone C, Ezell J, Jones-Farmer L (2014) Data quality for data science, predictive analytics, and big data in supply chain management: An introduction to the problem and suggestions for research and applications. Int J Product Econ 154:72–80

Jiang B, Yao T, Feng B (2008) Valuate outsourcing contracts from vendors’ perspective: a real options approach. Decis Sci 39(3):383–405

Jörnsten K, Nonås S, Sandal L, Ubøe J (2013) Mixed contracts for the newsvendor problem with real options and discrete demand. Omega 41(5):809–819

Kenyon C (2005) Optimal price design for variable capacity outsourcing contracts. J Revenue Pricing Manag 4(2):124–155

Kouvelis P, Milner J (2002) Supply chain capacity and outsourcing decisions: the dynamic interplay of demand and supply uncertainty. IIE Trans 34(8):717–728

King W, Torkzadeh G (2008) Information systems offshoring: research status and issues. MIS Q 32(2):205–225

Lim W, Tan S (2010) Outsourcing suppliers as downstream competitors: biting the hand that feeds. Eur J Oper Res 203(2):360–369

Liu B (2007) Uncertainty theory. In Uncertainty theory (pp. 205–234). Springer, Berlin

Liu B (2009) Some research problems in uncertainty theory. J Uncertain Syst 3(1):3–10

Liu B (2010) Uncertainty theory: a branch of mathematics for modeling human. Springer, Berlin

Liu B (2015) Uncertainty theory, 4th edn. Springer, Berlin

Liu Z (2005) Stackelberg leadership with demand uncertainty. Manag Decis Econ 26(2):345–350

Liu Z, Nagurney A (2013) Supply chain networks with global outsourcing and quick-response production under demand and cost uncertainty. Ann Oper Res 208(1):251–289

Liu Z, Zhao R, Liu X, Chen L (2016) Contract designing for a supply chain with uncertain information based on confidence level. Appl Soft Comput. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2016.05.054

Ma H (2009) Research on operation outsourcing decision-making of chinese manufacturing industry. Master’s thesis, Lanzhou University

Markowitz H (1959) Portfolio selection: efficient diversification of investment. Wiley, New York

Niu B, Wang Y, Guo P (2015) Equilibrium pricing sequence in a co-opetitive supply chain with the ODM as a downstream rival of its OEM. Omega 57:249–270

Nosoohi I, Nookabadi A (2016) Outsource planning through option contracts with demand and cost uncertainty. Eur J Oper Res 250(1):131–142

Peng Z, Iwamura K (2010) A sufficient and necessary condition of uncertainty distribution. J Interdiscip Math 13(3):277–285

Rockafellar R, Uryasev S (2000) Optimization of conditional value-at-risk. J Risk 2(1):21–42

Smith A (2008) Dell plans to shake up business model, sell factories, reports say. http://www.dallasnews.com. Accessed date December 2, 2009

Spiegel Y (1993) Horizontal subcontracting. RAND J Econ 4(24):570–590

Tsai W, Hsu J, Chen C (2007) Integrating activity-based costing and revenue management approaches to analyse the remanufacturing outsourcing decision with qualitative factors. Int J Revenue Manag 1(4):367–387

Van Damme E, Hurkens S (2004) Endogenous price leadership. Games Econ Behav 47(2):404–420

Tsay A (2002) Risk sensitivity in distribution channel partnerships: implications for manufacturer return policies. J Retail 78(2):147–160

Wang G, Gunasekaran A, Ngai E, Papadopoulos T (2016) Big data analytics in logistics and supply chain management: certain investigations for research and applications. Int J Prod Econ 176:98–110

Wang K, Wu C (2015) Product design outsourcing in competitive markets. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2693939

Wang Y, Niu B, Guo P (2013) On the advantage of quantity leadership when outsourcing production to a competitive contract manufacturer. Prod Oper Manag 22(1):104–119

Wu J, Yue W, Yamamoto Y, Wang S (2006) Risk analysis of a pay to delay capacity reservation contract. Optim Methods Softw 21(4):635–651

Wu X, Zhao R, Tang W (2014) Uncertain agency models with multidimensional incomplete information based on confidence level. Fuzzy Optim Decis Mak 13(2):231–258

Yang S, Yang J, Abdel-Malek L (2007) Sourcing with random yields and stochastic demand: a newsvendor approach. Comput Oper Res 34(12):3682–3690

Yang K, Zhao R, Lan Y (2014) The impact of risk attitude in new product development under dual information asymmetry. Comput Ind Eng 76(3):122–137

Yang X, Gao J (2016) Linear-quadratic uncertain differential game with application to resource extraction problem. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst 24(4):819–826

Yang X, Gao J (2017) Bayesian equilibria for uncertain bimatrix game with asymmetric information. J Intell Manuf 3(28):515–525

Zhu S, Fukushima M (2009) Worst-case conditional value-at-risk with application to robust portfolio management. Oper Res 57(5):1155–1168

Yan Y, Zhao R, Lan Y (2017) Asymmetric retailers with different moving sequences: group buying vs. individual purchasing. Eur J Oper Res 261(3):903–917

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 71471126 and Hubei Province Natural Science Foundation of Key Project under Grant No. 2015CFA144.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent is obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Communicated by Y. Ni.

Appendix

Appendix

Proof of Theorem 1

Because the function \(\pi _{1}(q_{1},q_{2};x,y)\) is strictly increasing with x and is strictly decreasing with y, the chance constraint \(M\{\pi _{1}(q_{1},q_{2};\alpha _{1})\geqslant \pi _{01}\}\geqslant \alpha _{1}\) is equivalent to

Since \(\pi _{m1}(q_{1},q_{2};\alpha _{1})=max\{\pi _{01}\}\), the OEM’s maximum profit \(\pi _{m1}(\cdot ,\cdot )\) under its acceptable confidence level \(\alpha _{i}\) satisfies

Similarly, the CCM’s maximum profit \(\pi _{m2}(\cdot ,\cdot )\) under her acceptable confidence level \(\alpha _{2}\) is

By Eqs. (11) and (12), we obtain Eqs. (5) and (6). The proof of the theorem is completed. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 1

From Theorem 1, Eqs. (5) and (6) can be rewritten as

and

From Eqs. (13) and (14), the best response functions are:

Solving these two equations, the conclusion in Theorem 2 can be obtained. \(\square \)

Proof of Theorem 2

The proof of this theorem is similar to that of Theorem 1. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 2

Model (7) can be turned into the following one,

It can be shown that the optimal production quantity of the CCM is

Substituting \(q^{f}_{2}(q_{1})\) into the OEM’s profit function and maximizing the objective function yields the optimal production quantity:

Moreover, the corresponding optimal decision for the CCM is

Substituting \(q^{l}_{1}\) and \(q^{f}_{2}\) into the OME’s and CCM’s profit functions yields profits of two participants, and the conclusion in Theorem 2 can be obtained. The proof of the theorem is completed. \(\square \)

Proof of Theorem 3

The proof of Theorem 3 is similar to that of Theorem 1. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 3

The proof of Proposition 3 is similar to that of Proposition 2. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 4

When \(w<\min \{w^{O}, w^{C}\}\) and \(\frac{2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}<k\leqslant \frac{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2}\), both the OEM and CCM exist in the market in all three basic games. At first, we compare \(w^{O}\) and \(w^{C}\), shown as follows.

Then, the sign of \(w^{C}-w^{O}\) depends on that of \([2\gamma \Phi ^{-1}(1-\alpha _{1})-(1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1}))\Phi ^{-1}(1-\alpha _{2})]\). This is because \(w^{C}-w^{O}<0\) if \(k< \frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }\) and \(w^{C}-w^{O}>0\) if \(k> \frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }\). Thus, we still need to look at whether \(\frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }\) belongs to the range of k by comparison between \(\frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }\) and \(\frac{2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\) and that between \(\frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }\) and \(\frac{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2}\). We show that

We can find that \(\frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }>\frac{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2}\) if \(\gamma <\frac{1}{4-2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\) and \(\frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }<\frac{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2}\) if \(\gamma >\frac{1}{4-2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\). In summary, both the OEM and CCM exist in the market in all three basic games. And the range of the wholesale price in which all three games exist is:

-

(i) If \(0\leqslant \gamma <\frac{1}{4-2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\), \(\frac{2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}<k\leqslant \frac{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2}\), then \((0, w^{C})\).

-

(ii) If \(\frac{1}{4-2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\leqslant \gamma <1\),

-

If \(\frac{2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}<k\leqslant \frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }\), then \((0, w^{C})\),

-

If \(\frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }<k\leqslant \frac{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2}\), then \((0, w^{O})\).

-

Secondly, we compare the performances of the OEM and the CCM under the three basic games yields in Proposition 4. First, we have

Then, the sign of \(\pi _{1}^{l}-\pi _{1}^{f}\) depends on that of

Define \(w_{A}={\frac{\Phi ^{-1}(1-\alpha _{1})-2\,\Phi ^{-1}(1-\alpha _{2})}{\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})-4\,\gamma +1}}\). Then, according to the above-mentioned results and \(\frac{1}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}<\frac{1}{4-2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\), we analyze separately in \(\left[ 0, \frac{1}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\right) \), \(\left( \frac{1}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}, \frac{1}{4-2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\right) \), \(\left[ \frac{1}{4-2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}, 1\right) \)

Case 1 When \(\frac{1}{4-2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\leqslant \gamma <1\), we have

Thus, \(\pi _{1}^{f}>\pi _{1}^{s}\) if \(w>w_{A}\) and \(\pi _{1}^{f}<\pi _{1}^{s}\) if \(w<w_{A}\). Furthermore, we show that

It can be verified that the sign of the above two equations depends on \((1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1}))\Phi ^{-1}(1-\alpha _{2})-2\gamma \Phi ^{-1}(1-\alpha _{1})\). Then, we have \(w_{A}<w^{O}<w^{C}\) if \(k>\frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }\) and \(w^{C}<w^{O}<w_{A}\) if \(k<\frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }\). Hence, we have two subcases to consider:

-

a)

\(\frac{2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}<k\leqslant \frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }\) and \(0<w<w^{C}\), then \(\pi _{1}^{f}-\pi _{1}^{s}<0\).

-

b)

\(\frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }<k\leqslant \frac{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2}\), then \(\pi _{1}^{f}-\pi _{1}^{s}<0\) if \(0<w<w^{A}\) while \(\pi _{1}^{f}-\pi _{1}^{s}>0\) if \(w^{A}<w<w^{O}\). Additionally, \(\pi _{1}^{f}-\pi _{1}^{s}=0\) if \(w=w_{A}\).

Case 2 When \(\frac{1}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}<\gamma <\frac{1}{4-2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\), we have \(\pi _{1}^{f}>\pi _{1}^{s}\) if \(w>w_{A}\) and \(\pi _{1}^{f}<\pi _{1}^{s}\) if \(w<w_{A}\). In addition, \(\frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }>\frac{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2}\), thus we obtain \(w^{C}<w^{O}<w^{A}\). In summary, we have \(\pi _{1}^{f}-\pi _{1}^{s}<0\) if \(\frac{2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}<k\leqslant \frac{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2}\) and \(0<w<w^{C}\).

Case 3: When \(0\leqslant \gamma <\frac{1}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\), similar to the second case, we obtain \(\pi _{1}^{f}-\pi _{1}^{s}>0\) if \(\frac{2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}<k\leqslant \frac{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2}\) and \(0<w<w^{C}\).

The proof of the theorem is completed. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 5

The proof of this theorem is similar to that of Theorem 1.

Here

We can see that the sign of \(\pi _{2}^{f}-\pi _{2}^{s}\) is the same as that of (17)

Define \(w_{B}=\frac{\left( \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})^{2}-16\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1}\right) +32)\Phi ^{-1}(1-\alpha _{2})+\left( 6\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})-16\right) \Phi ^{-1}(1-\alpha _{1})}{8\gamma (2-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1}))(4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1}))-16+6\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\).

And note that \(w_{A}<w_{B}<w^{O}<w^{C}\) if \(k>\frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }\) and \(w^{C}<w^{O}<w_{B}<w_{A}\) if \(k<\frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }\), and note that \(\frac{16-6\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{8(2-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1}))(4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1}))}<\frac{1}{4-2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\). So we have three cases to consider:

-

(i) \(0\leqslant \gamma <\frac{8-3\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{4(2-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1}))(4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1}))}\), \(\frac{2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}<k\leqslant \frac{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2}\) and \(0<w<w^{C}\), then \(\pi _{2}^{f}-\pi _{2}^{s}>0\).

-

(ii) \(\frac{8-3\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{4(2-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1}))(4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1}))}<\gamma <\frac{1}{4-2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\), \(\frac{2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}<k\leqslant \frac{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2}\) and \(0<w<w^{C}\), then \(\pi _{2}^{f}-\pi _{2}^{s}<0\).

-

(iii) \(\frac{1}{4-2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\leqslant \gamma <1\), we have two subcases

-

a)

\(\frac{2\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}<k\leqslant \frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }\) and \(0<w<w^{C}\), then \(\pi _{2}^{f}-\pi _{2}^{s}<0\).

-

b)

\(\frac{1+\gamma \Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2\gamma }<k\leqslant \frac{4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}{2}\), \(\pi _{1}^{f}-\pi _{1}^{s}<0\) if \(0<w<w^{B}\) while \(\pi _{2}^{f}-\pi _{2}^{s}>0\) if \(w^{B}<w<w^{O}\). Additionally, \(\pi _{1}^{f}-\pi _{1}^{s}=0\) if \(w=w^{B}\). The proof of the theorem is completed.

-

a)

\(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 6

According to the results of above three games, we can obtain all the basic games exist when \(\gamma _{1}<\gamma <\gamma _{2}\). Here,

From Eqs. (16) and (17), we denote \(\gamma _{A}=\frac{2\Phi ^{-1}(1-\alpha _{2})-\Phi ^{-1}(1-\alpha _{1})+w}{w(4-\Psi ^{-1}(\alpha _{1})}\), and

Similar to the proofs of Propositions 5 and 6, we have \(\pi _{1}^{f}-\pi _{1}^{s}>0\) if \(\gamma >\gamma _{A}\) and \(\pi _{2}^{f}-\pi _{2}^{s}>0\) if \(\gamma >\gamma _{B}\). Because \(\gamma _1<\gamma _{A}<\gamma _{B}<\gamma _2\), the conclusion in Proposition 6 can be obtained. \(\square \)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, H., Yan, Y., Liu, Z. et al. Effect of risk attitude on outsourcing leadership preferences with demand uncertainty. Soft Comput 22, 5263–5278 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-017-2977-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-017-2977-9