Abstract

Immersive virtual reality (IVR) offers novel and promising ways of continuously adapting training content and difficulty to the individual trainee, thus paving the way for an improved fit between training content and trainee needs. The objective of the present study was to investigate the efficiency of utilising self-efficacy and performance measures to continuously adapt training content to the individual trainee. Using a preregistered, between-subjects experiment, 130 participants were randomly assigned to receive virtual training content that was either based on behavioural measures at the beginning of the study (fixed training) or that continuously adapted to the behaviour of the trainee (adaptive training). The results revealed no significant difference between the groups for either performance or self-efficacy, suggesting that the additional development required for fully adaptive training may be unwarranted in some cases. Further research should investigate when the additional complexity of adaptive training is outweighed by enhanced efficiency. That said, results revealed an overall beneficial effect of IVR-based training. However, while IVR had an overall positive effect on performance, transfer was only observed to a limited extent. Specifically, participants improved in both accuracy (d = −0.41) and speed (d = −0.43) on a virtual performance test, while performance on a real equivalent (i.e., transfer of skill) showed improved accuracy (d = −0.25) but reduced speed (d = 0.17). In other words, the study demonstrates that performance measures in IVR should not necessarily be expected to transfer to similar tasks outside IVR without a potential loss in performance, emphasising the need for future studies to include measures of skill transfer when investigating IVR-based training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Immersive Virtual Reality (IVR) refers to technologies that immerse the user into a fully-engaging, interactive digital environments, simulating real or imagined worlds. IVR is increasingly being viewed as a vital tool for training across various domains (Abich IV et al. 2021; Checa & Bustillo 2020). IVR is particularly useful for complex, dangerous, or critical tasks, offering a safe and controlled setting for skill development and assessment. Prior research suggests that IVR training may enhance skill acquisition (Radhakrishnan et al. 2023a, b) and increase learner engagement (Makransky et al. 2019), however, there is a growing recognition of the need for further research into more advanced training techniques, such as adaptive training (Marougkas et al. 2023). The majority of computer-assisted training follows a one-size-fits-all model, where a fixed training session is given to all trainees. However, differences in trainee abilities, needs, and learning patterns means that such uniform training risks being ineffective (i.e., either too easy or too difficult) for some trainees (Vaughan et al. 2016). Adaptive training in IVR, which adjusts difficulty or content of the training based on trainee behaviour, is seen as a promising but relatively unexplored area for enhancing the effectiveness of IVR training (Zahabi & Abdul Razak 2020). The increasing technological advancement of IVR technology presents novel potential for implementing this type of training, where the headset is used to collect real time behavioural data, which is then used to adjust training content to the specific needs of the trainee. However, due to the novelty of the technology, several questions remain unanswered.

First, adaptive training increases the required complexity of IVR applications, begging the question of whether the higher development costs are outweighed by heightened training outcomes. Second, multiple approaches can be utilised when developing the adaptive logic. Specifically, Kelley (1969) focused on adaptive training based on traditional performance measures, whereas Zahabi and Abdul Razak (2020) highlighted the potential of considering alternative variables. Third, while prior empirical research suggests beneficial outcomes of IVR-based training (Zahabi & Abdul Razak 2020), the degree of transfer, i.e., whether the heightened training outcome applies to performance in the real world and not just in IVR, has received less attention. Even fewer studies have included performance measures both in- and outside IVR.

The present paper adds to the current empirical research by addressing these gaps in a controlled, preregistered, between-subjects experiment. Using a sample of 130 participants, IVR-based fine motor skills training using fixed training, where training content was based on an initial measure of trainee behaviour, was compared to fully adaptive training, where training content continuously adjusted based on trainee performance. To explore the potential of novel forms of adaptive logic, both trainee performance and self-efficacy were measured and utilised to adjust training content. Furthermore, to address the question of training transfer, performance in the form of speed and accuracy was measured both in a virtual and physical environment.

The subsequent sections of the paper is structured as follows—Sect. 2 delves into the existing literature on IVR training, self-efficacy and adaptive training, ending with a sub-section listing the generated hypotheses. Section 3 presents methodology, development of the IVR application, and materials used. The results of the experiment are analysed in Sect. 4, containing both the main as well as exploratory analyses. Section 5 discusses these findings in the context of existing literature as well as the limitations of the study, followed by a conclusion in Sect. 6.

2 Related works

2.1 Training in virtual reality

Learning and training in (IVR) have been employed across various domains, ranging from education, rehabilitation, training of medical staff and industrial workers, focusing on cognitive and psychomotor skills (Borst et al. 2018; Jensen & Konradsen 2018; Winther et al. 2020). The literature on training in IVR primarily relates to higher education (Hamilton et al. 2021) and the teaching of procedural and safety knowledge for industrial training purposes (Feng et al. 2018). In contrast, motor skill training literature in IVR has been dominated by medical use cases, particularly in surgical and dental domains that require fine motor skills (Radhakrishnan et al. 2021). Researchers have investigated the relative advantages of IVR-based training over other media, e.g., video training (Winther et al. 2020) or other immersive media conditions (Bertrand et al. 2017) and variations within IVR, such as different levels of visual or haptic fidelity (Huber et al. 2018; Jain et al. 2020), user characteristics (Shakur et al. 2015), and training methods (Harvey et al. 2021). However, the results of these studies have been mixed with some support for the use of IVR over physical training for hip arthroplasty surgery (Hooper et al. 2019) and catheter insertion (Butt et al. 2018) immediately after training but with limited difference one week later (Butt et al. 2018). Furthermore, in a comparison of IVR to desktop VR training, Frederiksen et al. (2020) found that IVR was less effective and caused more cognitive load among students of laparoscopic surgery. Thus, the effectiveness of IVR training compared to other types of training remains inconclusive and an open research topic (Checa & Bustillo 2020), especially in the case of IVR-based motor skill training (Coban et al. 2022).

A fundamental assumption of research on simulation-based training is that skills developed in IVR can be transferred to the real world (Gegenfurtner et al. 2014, 2013). However, with prior research highlighting that transfer becomes increasingly difficult the bigger difference there is between the context during training and the context when retrieving the skill later (Ragan et al. 2015) it is no surprise that skill transfer of IVR-based training has been questioned (Jensen & Konradsen 2018). Levac et al. (2019) notes in a review of VR rehabilitation literature that discrepancies in sensory-motor information between virtual and real environments can lead to different perceptual-motor couplings, potentially hindering skill transfer. Although there is support for virtual training having a beneficial effect outside the virtual environment (Cooper et al. 2021; Murcia-López & Steed 2018), even regardless of interaction fidelity (Bhargava et al. 2018), it is not uncommon for research to purely include IVR-based outcome measures without a measure of skill transfer (Frederiksen et al. 2020; Huber et al. 2018; Lang et al. 2018). Including measures of performance both in- and outside IVR provides valuable information about the potential loss that is to be expected when transferring a skill from one setting to another and should therefore be including when exploring the potential of IVR-based training.

2.2 Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is used to refer to one’s perceived capabilities for learning of or performing an action (Schunk & DiBenedetto 2016). Individuals with high self-efficacy are generally more willing to take on difficult tasks and are more motivated to achieve better results (Bandura 1997; Wei et al. 2021). Research has supported the role of self-efficacy not only in relation to learning outcomes, but also in training (Gegenfurtner et al. 2014). Specifically, self-efficacy is an important predictor of performance on the task at hand (Feltz et al. 2008; Moritz et al. 2000; Rosenqvist & Skans 2015) as well as future performance on similar tasks (Ding et al. 2020; Pascua et al. 2015; Stevens et al. 2012). For example, when Chauvel et al. (2015) had participants practise golf putting on holes made to be perceived as either small or large, self-efficacy was found to be significantly higher when the hole was perceived as larger (i.e., making the task seem easier). Furthermore, although the holes were the same size, performance was significantly higher for the task perceived as easier, both on the task and on a retention task the following day. The same tendency has been replicated in multiple other tasks related to motor skills, such as golfing (Abbas & North 2018; Chauvel et al. 2015), dart throwing (Ong et al. 2015), and soccer (Mousavi & Iwatsuki 2021). When developing training content, it is therefore crucial to consider how to optimise training outcomes by supporting the individual’s level of self-efficacy.

According to the social cognitive theory, major influences of self-efficacy include personal experiences of success, vicarious experiences (i.e., observing others succeed), social persuasion, and physiological factors (Bandura 1977). Amongst these, the most important factor is personal experiences of success (Schunk & DiBenedetto 2016). In other words, the experience of being able to complete a task or accomplish a goal at a satisfactory level is a key predictor of the individual’s level of self-efficacy, which in turn predicts performance gain. As such, the majority of research on self-efficacy and skills training has focused on the role of perceived success (Wulf & Lewthwaite 2016), supporting a stronger link between performance feedback and improvements when the feedback is given for successful rather than unsuccessful trials (Abbas & North 2018; Saemi et al. 2012) as well as improved retention and skill transfer (Wulf et al. 2014).

According to the cognitive affective model of immersive learning (CAMIL), IVR is characterised by higher levels of presence and agency than traditional media, which in turn supports learning outcomes through cognitive and affective factors such as self-efficacy (Makransky & Petersen 2021). Indeed, when compared with less immersive media, IVR tends to show beneficial effects on self-efficacy in an educational setting (Huang et al. 2022; Klingenberg et al. 2020; Shu et al. 2019). However, while multiple studies have found evidence of the role of self-efficacy in simulation-based training (Gegenfurtner et al. 2014, 2013), only few have narrowed the scope to IVR-based training (Buttussi & Chittaro 2017; Lehikko 2021; Liu et al. 2022; Pulijala et al. 2018; Radhakrishnan et al. 2023a, b; Song et al. 2021). Furthermore, these rarely include sufficient measures of self-efficacy and training outcomes to fully explore the role of self-efficacy in relation to the effectiveness of the training.

Thus, an abundance of research supports the link between self-efficacy and learning or training as well as the role of feedback during training. Given the role of self-efficacy in relation to performance gain, it is expected to be especially relevant for IVR-based training, which has the potential to be formed and tailored to the individual in ways impossible with prior technology. That said, limited research has investigated ways to utilise the role of trainee self-efficacy when designing IVR-based training content. The present study aimed to address this gap by investigating options for implementing and utilising dynamic measures of self-efficacy throughout training with the aim of increasing both trainee self-efficacy and performance.

2.3 Adaptive training

Tailoring, or adapting, training content to the individual trainee is not a new approach. On the contrary, it has been over 50 years since Kelley (1969, p. 547) described adaptive training as requiring that “[…] performance be continuously or repetitively measured in some way, and that the measurement be employed to make appropriate changes in the stimulus, problem, or task.” In other words, in adaptive training, technology is used in the place of a skilled instructor with the aim of continuously monitoring the responses of the individual and adjusting training content for optimal training outcomes. Non-adaptive training, where a one-size-fits-all approach is used, is generally easier and cheaper to implement, but with the risk of a mismatch between training content and trainee needs in relation to factors such as difficulty, engagement, and training focus (Zahabi & Abdul Razak 2020).

A further distinction is made between fixed training, where training content is modelled exclusively based on measures prior to the start of the training session, and adaptive training, where measures of trainee behaviour and adjustments of training content happens throughout the training session (Gerbaud et al. 2009; Kelley 1969). While fixed training is relatively easy to implement, it fails to take into account the difference in improvement rates between individuals, with the risk of training content being too easy for some individuals and too challenging for others (Kelley 1969). For example, underperforming during the initial behavioural measure will result in fixed training being too easy throughout the whole training session, whereas adaptive training content will still be able to quickly adjust to the appropriate difficulty. Therefore, aiming to implement adaptive training is to be preferred, but requires three core elements. First, a continuous measure of trainee behaviour is required to monitor relevant aspects of the individual’s changing performance throughout the session (Kelley 1969). The term trainee behaviour is used here to highlight that the measure need not relate to performance on the task at hand, but can also be measures of learning style, psychophysiological measures, such as eye-tracking, ECG, or EDA, or psychological factors, such as self-efficacy, immersion, or engagement. Furthermore, the chosen behaviour can either be measured throughout the whole training session or between different parts of the training session. As for the second core element, a feature of the training content, termed adaptive variable, must be chosen based on relevance for training, such as training difficulty, feedback, or training focus (Zahabi & Abdul Razak 2020). Third, adaptive logic is implemented to describe the relationship between the trainee behaviour and the adaptive variable, such as increasing the difficulty of training when trainee performance increases.

It is generally assumed that the increased complexity of implementing fully adaptive training (as opposed to fixed training) is accompanied by increased training outcomes through the superior fit between trainee needs and training content (Kelley 1969; Zahabi & Abdul Razak 2020). In a systematic review of current usage of virtual reality-based adaptive training, Zahabi and Abdul Razak (2020) notes that most studies were concept or feasibility studies and as such did not investigate the effectiveness of adaptive training. Of the few that did, the results are mixed, with some support for adaptive over non-adaptive training (Gray 2017; Lang et al. 2018; Ma & Bechkoum 2008; Verniani et al. 2024; Wang et al. 2017), whereas other studies found no difference between the two (Billings 2012; Serge et al. 2013). That said, while results on primary outcome measures may be mixed, other benefits have been observed, such as increased self-efficacy (Yovanoff et al. 2018) and increased engagement (El-Sabagh 2021).

Although this indicates that the use of adaptive training is already being investigated, only few studies utilised truly adaptive training (as opposed to fixed training; e.g., Klock et al. 2020; Mariani et al. 2020) and even fewer has done so using immersive virtual reality (Vaughan et al. 2016; Zahabi & Abdul Razak 2020). The few current explorations of IVR-based adaptive training were mainly based on concept development (e.g., de Lima et al. 2022; Drey et al. 2020; Iván Aguilar Reyes et al. 2022) and pilot studies (e.g., Chiossi et al. 2022; Muñoz et al. 2016; Oagaz et al. 2022). Therefore, robust, controlled experiments with larger samples are required to move beyond initial explorations of adaptive IVR training, with the aim of investigating the effect of adding the additional layer of complexity as compared to fixed training. While doing so, research should ideally also implement measures of transfer of skills from virtual training to the desired setting to investigate the effect of training features on skill transfer. Furthermore, Zahabi and Abdul Razak (2020) highlights the need for adaptive training where trainee kinematic or kinetic information is used for continuous adaptation content and where the used adaptive variable goes beyond content difficulty, for example by providing adaptive feedback to the user.

To address these gaps, the present study aimed to compare adaptive and fixed IVR-based training in a controlled experiment, following the assumption of Kelley (1969) that higher levels of adaptiveness should be superior for training outcomes. Moreover, following the arguments of Zahabi and Abdul Razak (2020), adaptive logic was formed around multiple sources of information, including performance data and psychological measures of self-efficacy. Lastly, adaptive variables were based on not only adjusting task difficulty, but also features of training content in the form of training focus.

2.4 Hypotheses

The primary aim of the present study was thus to investigate the use of adaptive IVR-based training in a controlled lab experiment. Two hypotheses were formulated in relation to the effect of adaptive IVR training whereas the third focused on the relationship between self-efficacy and performance.

The majority of prior research has made the case that adaptive training should be superior to fixed training (Kelley 1969; Zahabi & Abdul Razak 2020). Therefore, adaptive virtual training was expected to lead to higher performance as compared to fixed virtual training (Hypothesis 1). To investigate differences in skill transfer, performance was not only measured on a virtual task, but also on an identical physical version of the task.

Research on self-efficacy suggests that adjusting difficulty and content to make successful experiences possible and visible to the trainee is of great importance when aiming to support trainee confidence (Hutchinson et al. 2008; Saemi et al. 2012). Based on the increased ability to adapt to the needs of the individual trainee, adaptive training was expected to lead to higher self-efficacy than fixed training (Hypothesis 2).

A third hypothesis focused on the relationship between self-efficacy and performance, where self-efficacy was expected to affect the relationship between training and performance (Hypothesis 3).

Additionally, exploratory analyses focused on investigating the level of transfer from virtual training to a physical equivalence of the task as well as dynamic changes in performance and self-efficacy throughout virtual training.

3 Methods and materials

3.1 Participants and experimental design

130 individuals (Mage = 25.37, SD = 6.07; 51.5% female) were recruited for the study. The sample size was determined based on a priori power analysis to estimate the required sample size to detect a medium effect, based on effect sizes reported in previous studies on adaptive training (Aguilar Reyes et al. 2023; Gray 2017), in the primary analysis using one-tailed tests with high statistical power (1–β = 0.80) and an alpha level of 0.05. All statistical analyses include the full sample of N = 130.

The study was conducted at the Cognition and Behavior (COBE) Lab at Aarhus University and preregistered using AsPredicted. Preregistration, study materials, and study data are available on the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/jmg9t/).

After arriving at the lab, participants completed a short familiarisation task and a demographic questionnaire. Before and after virtual training, a physical and virtual version of the buzz wire task, where the participant had to move a loop along a wire as quickly and accurately as possible, were completed to measure changes in performance. Before both physical versions of the task, self-efficacy were measured using a 6-item scale. During virtual training, participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions, adaptive or fixed training, and completed 10 repetitions of the virtual buzz wire task with changing training focus and difficulty. After each repetition of the virtual wire, participants rated their confidence in completing the task quickly and accurately to measure dynamic changes in self-efficacy, which was also used to adjust adaptive logic for training content. The study duration was approximately 35 min and participants were paid approximately 11.5 euro for taking part in the study (Fig. 1).

3.1.1 Motor skill task

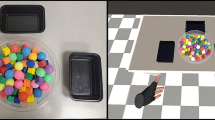

In the study, participants were instructed to grasp the handle as illustrated in Fig. 2 and move the connected metal loop along a wire as quickly and accurately as possible, minimising contact between the loop and the wire. This task, popularly know as the ‘buzzwire task’, though simplistic, serve as an effective proxy for various fine motor skills required in real-world applications. For instance, similar hand–eye coordination and precise movement control are crucial in medical procedures like microsurgery (Mariani et al. 2020) and industrial tasks such as assembly line work (Ulmer et al. 2022). In fact, Lee et al. (2022) holds that the precise motions required by the buzzwire task are applicable for high precision manufacturing tasks. By studying this fundamental task, one can potentially gain insights into the applicability of adaptive training for a wider range of practical skill training domains.

In the physical version of the task, a 3D-printed replica of the Oculus Quest controller was presented as the handle, while the controller itself was used in the virtual version (Fig. 2). Both the virtual and physical tests featured wires measuring 52 cm in length with eleven 90° bends spanning the x, y, and z axes from the starting point (labelled 'A') to the finishing point (labelled 'B'). For the physical setup, electrical circuits detected contact between the loop and the wire, as well as between the loop and the associated start (‘A’) and end points (‘B’). This data was transmitted to the iMotions data collection platform.

The IVR test setup was created with the Unity3D game engine and designed to maintain identical wire dimensions to the physical test. Collision detection code implemented using C# scripting inside Unity3D measured the contact between the virtual loop and the virtual wire. The data was then used to measure total contact time, defined as the time when the loop is in contact with the wire (in seconds), as well as the task completion time, defined as the time taken to move the loop from A to B (in seconds).

When the participant made a mistake in the virtual setup, i.e., the loop touched the wire, there was nothing to physically restrict the participant’s hand, unlike the physical version where there was an actual wire to provide resistance. To provide a feeling of touching the wire, a haptic vibration to the participant’s hand was provided using the Oculus controller. By the time contact is made, the loop would already have passed through the wire creating an unrealistic effect for the participant. To solve this, a ‘ghost effect’ (Fig. 3) was programmed to show a blue translucent loop at the contact position where the loop passes through the virtual wire. A dotted red line indicated the direction where the user should move to re-join the wire, thus helping the participant understand how to bring their loop back into the wire, at which point the blue translucent ‘ghost’ disappears. A previous study using a similar VR setup found that visual feedback in the form of this “ghost effect” did not result in any difference in training outcomes when compared to haptic feedback modalities (Radhakrishnan et al. 2023).

3.1.2 Virtual training

Participants used an Oculus Quest 2 head-mounted display (HMD) connected to a PC, functioning in PC VR mode. The virtual environment was developed with the Unity3D (version 2019.4) game engine. The Oculus SDK supplied the position and rotation information for both the controller and the HMD, which were subsequently applied to control the virtual loop and the participant’s viewpoint in the three-dimensional space of the virtual setting (see Fig. 4). To reduce novelty effects, participants initially performed a virtual task that required moving the loop along a short, straight wire, familiarising themselves with the mechanics of IVR before starting the main training. The training consisted of ten trials that focused on either speed or accuracy. The wire was 57 cm long (from end to end), featuring eighteen 90-degree bends and extending 21 cm horizontally. This configuration was maintained across all ten trials.

Speed-focused training A green speed primer ring moved at a constant pace, determined by the participant’s prior performance. Participants were instructed to concentrate on completing the task by matching or surpassing the speed primer’s pace while maintaining the requisite level of accuracy.

Accuracy-focused training An accuracy primer, represented by a green ring, moved in tandem with the participant’s loop, maintaining optimal orientation and distance from the wire, serving as a reference to minimise errors. A red bar signified the accuracy level, where 100% corresponds to the accuracy from a previous trial. The bar diminished in size as the participant made contact, proportionate to the current total contact time and the previous total contact time. For example, if the participant had a total contact time of 5 s in the previous trial and the current contact time reaches 2.5 s, the red bar would shrink by 50%.

3.1.3 Adaptive logic and conditions

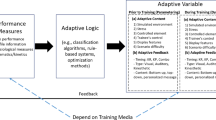

Two sets of adaptive logic were developed for the study. The first was based on the majority of prior research (Iván Aguilar Reyes et al. 2022; Zahabi & Abdul Razak 2020), using performance measures (trainee behaviour) to adjust difficulty of the primer for each repetition (adaptive variable). The second adaptive logic used participant self-efficacy (trainee behaviour) to adjust the training focus to either speed- or accuracy-focused training (adaptive variable).

In the beginning of the study, participants were randomly assigned to either fixed or adaptive training. In fixed training, training content was based on performance and self-efficacy during the initial virtual pre-test, whereas training content in adaptive training was continuously adjusted based on performance and self-efficacy in the most recent repetition of the task. With fixed training, performance and self-efficacy were measured during the virtual pre-test, whereafter difficulty was set to match the pre-test performance with a fixed increase in difficulty of 3% for each repetition. The increase in difficulty was based on prior research (Lui et al. 2023; Radhakrishnan et al. 2023), matching the average improvements in performance on the virtual buzz wire task. Additionally, fixed training included 8 out of 10 repetitions of the type of training (speed vs. accuracy) the individual participant reported lowest confidence in. With adaptive training, the difficulty of each repetition of the task was set to match the performance of the participant in the last repetition of the same type. Training focus was continuously adjusted in the same way, by including the type of training that was reported the least amount of confidence in during the last repetition. To ensure that no participant received only one type of training focus, the adaptive training would include no more than 8 of the same type of training focus (see also Fig. 5). This was done by reversing the training content of the 5th and 10th repetition if the participant had received, respectively 4 and 8 of the same type of training during adaptive training. In total, 24 participants (36.92%) in the adaptive condition received at least one of these reversed trials, with 13 (20%) receiving a single reversal and 11 (16.92%) receiving two reversals.

Adaptive logic determining training content for the adaptive condition (left) and fixed condition (right). SE = self-efficacy. Participants receive either speed- or accuracy-focused training (see Sect. 3.1.2) depending on initial SE scores (for the fixed condition) or SE scores on the previous repetition (for the adaptive condition) up to a maximum of 8 out of 10 of the same training focus

3.2 Materials

3.2.1 Self-efficacy

A scale was constructed based on Bandura (2006) to measure self-efficacy. Participants rated their confidence by typing a number from 0 (Not at all certain) to 100 (Highly certain) on six items. The items related to completing the buzz wire task with high accuracy (e.g., I can complete the buzz wire task with a minimal number of touches), high speed (e.g., I can control the fine motor movements necessary to complete the buzz wire task quickly), or a combination of the two (e.g., I can maintain a high level of speed and accuracy while completing the buzz wire task). The full instructions and remaining items can be found on OSF. As described in the preregistration, main analyses were based on change in self-efficacy on the overall scale, calculated by subtracting the pre-measured score (M = 54.09, SD = 19.31) from the post-measured score (M = 45.31, SD = 19.07). All items were highly correlated (correlations between r = 0.58 and r = 0.85) with sufficiently high Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.94; α = 0.94).

After each repetition of the buzz wire, participants were asked to rate their confidence in completing the buzz wire task quickly and accurately on a scale from 0 to 100. These two items were used to inform the adaptive logic and for explorative analyses focusing on dynamic changes in self-efficacy.

3.2.2 Performance

Prior studies using the same buzz wire task measured performance on one repetition of the buzz wire task before and after training (Radhakrishnan et al. 2023a, b). To increase sensitivity of the outcome measure, the present study lengthened the pre- and post-measure by having participants complete the task in both directions.

Two performance measures were used based on prior research on motor skills training (Radhakrishnan et al. 2021, Radhakrishnan et al. 2023): speed and accuracy. Speed was measured as task completion time, meaning the time the participant spent on moving the loop through the wire. Accuracy was measured as contact time with the wire, indicating how much a participant touched the wire during the task. To convert these measures to a meaningful measure of improvements in performance and to account for differences in baseline performance, the main performance measures were the decrease in task completion time (i.e., improvement in speed) and decrease in contact time (i.e., improvement in accuracy) measured in percentage.

Additionally, the majority of prior literature investigating IVR-based training measured improvements in performance either inside IVR (Lang et al. 2018) or outside IVR (e.g., Koumaditis et al. 2020; Murcia-López & Steed 2018; Ulmer et al. 2022), but rarely both (e.g., Sportillo et al. 2015). In the present study, performance was measured both on a virtual and physical version of the buzz wire task to compare improvements between the two, thus reflecting skill transfer.

4 Results

4.1 Main effect of virtual training

Paired t-tests were conducted to investigate the overall effect of virtual training on performance and self-efficacy (see Table 1 for statistics). Analysis of the main effect of training revealed that both contact time (d = −0.41) and completion time (d = −0.43) were significantly lower on the virtual wire as a result of training. This was not the case for the physical wire, where contact time was significantly lower (d = −0.25) whereas completion time had increased (d = 0.17). In short, virtual training led to participants completing a virtual wire both quicker and with higher accuracy while completing a real wire slower but with higher accuracy than prior to training. Furthermore, virtual training had a medium effect on the virtual wire (d = −0.43 for speed & d = −0.41 for accuracy) but only a small effect on the physical wire (d = 0.17 & d = −0.25), indicating that although skill transfer was observed for accuracy, it was in a relatively limited degree. Improved accuracy on the virtual wire was positively correlated with improved accuracy (r (128) = 0.20, p = 0.022), but not speed (r (128) = −0.06, p = 0.503), on the physical wire, whereas improved speed on the virtual wire was positively correlated with improved speed (r (128) = 0.46, p < 0.001), but not accuracy (r (128) = 0.08, p = 0.399), on the physical wire (see also Table 3).

Unexpectedly, self-efficacy was significantly lower after training than before training (d = −0.46), suggesting that the virtual training led participants to report lower confidence in doing well on the task. To further explore trainee confidence, two repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted, analysing dynamic changes in self-efficacy for accuracy and speed throughout the 10 training repetitions. Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated for both accuracy, χ2(44) = 149.78, p < 0.001, and speed, χ2(44) = 141.45, p < 0.001, therefore the Greenhouse–Geisser correction tests were used. Tests of within-subjects effect showed a significant main effect of time for both self-efficacy for accuracy, F (6.78, 873.8) = 12.856, p < 0.001 partial η2 = 0.09, and speed, F (7.08, 1161) = 13.997, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.10. Furthermore, a significant linear trend was found for self-efficacy over time for both accuracy, F (1, 129) = 32.944, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.20, and speed, F (1, 129) = 18.445, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.13, indicating a general increase in self-efficacy for both accuracy and speed when measured after each training repetition (see also Fig. 6). Since visual inspection suggested that an inverse relationship exists between self-efficacy for speed and accuracy throughout training (Fig. 6), the change in self-efficacy was calculated across consecutive trials and a correlational analysis was conducted for these changes. Results showed a significant, negative relationship between changes in self-efficacy for accuracy and speed, r (1169) = −0.21, p < 0.001. This indicates that increases in one type of self-efficacy are associated with a decrease in the other type from trial to trial.

Similarly, two repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted to inspect dynamic performance scores in accuracy and speed (see Fig. 7). Note that lower scores indicate higher accuracy and speed. Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated for both accuracy, χ2(44) = 462.63, p < 0.001, and speed, χ2(44) = 324.24, p < 0.001. Tests of the within-subjects effect using a Greenhouse–Geisser correction likewise showed a significant main effect of time for both accuracy, F (4.88, 629.12) = 32.937, p < 0.001 partial η2 = 0.203, and speed, F (5.61, 723.26) = 13.729, p < 0.001 partial η2 = 0.10. Lastly, Significant linear trends for both accuracy, F (1, 129) = 95.58, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.43, and speed, F (1, 129) = 45.788, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.26, indicated a consistent improvement in accuracy and speed over time, with time explaining a notably larger proportion of the variance in accuracy (43%) than in speed (26%).

4.2 Main analysis: adaptive and fixed training

As specified in the preregistration, one-sided t-tests were utilised to investigate hypothesis 1 and 2, comparing adaptive (N = 65) and fixed (N = 65) virtual training. One-sided tests were used to increase power of the main analysis, justified by the fact that the study was preregistered and hypothesis 1 and 2 were directional (Cho & Abe 2013; Ruxton & Neuhäuser 2010). Independent t-tests indicated that the groups did not differ in age (p = 0.841), or any relevant baseline measures such as self-efficacy (p = 0.308) or aspects of performance (between p = 0.2 and p = 0.42). A Chi-Square test indicated that the groups did not differ in reported gender (p = 0.08).

One item during the post-test was used as a manipulation check (“Which type of training do you believe you received?”). A Chi-Square test showed no significant difference on the manipulation check (p = 0.66) with most participants in both the adaptive (54 of 65) and the fixed condition (51 of 65) assuming that they had received adaptive training.

Hypothesis 1

Adaptive virtual training leads to higher performance as compared to fixed virtual training.

The first hypothesis was not supported by the results, where no significant differences were found between the groups for improvements in contact time (d = 0.06) or completion time (d = 0.00) on the virtual task (Fig. 8). The same was the case for the physical transfer task, revealing no differences in either transfer contact time (d = 0.05) or completion time (d = 0.00). The full statistics can be viewed in Table 2. Exploratory analysis revealed no significant difference in training difficulty between the groups for accuracy-focused training, t (128) = 0.034, p = 0.973, 95% CI [−1.155, 1.194], d = 0.00 or speed-focused training, t (128) = 1.807, p = 0.073, 95% CI [−0.279, 0.614], d = 0.32.

While independent t-tests were pre-registered and used in the main-analysis, additional ANCOVAs were conducted with pre-test scores as covariates. The results from the ANCOVA analyses correspond with those of the independent t-tests and are available in the “Supplementary analyses” document on OSF.

Hypothesis 2

Adaptive virtual training leads to higher self-efficacy as compared to fixed virtual training

The second hypothesis assumed that adaptive training would lead to a higher increase in self-efficacy than fixed training. This was not supported by the results, revealing no statistically significant difference in change in self-efficacy between the groups (d = −0.10; Table 2).

Since no significant effect of experimental condition were found, and as stated in the preregistration for the study, no further analysis were conducted to explore the third hypothesis, which assumed that self-efficacy would affect the relationship between type of training and training outcomes.

4.3 Exploratory analysis: training type and training success

Training type. During virtual training, each repetition of the buzz wire task focused on either speed or accuracy, depending on the individual’s level of self-efficacy in the previous repetition (adaptive training) or in the virtual pre-test (fixed training). On average, participants received accuracy-focused training in 6.5 out of 10 repetitions of the buzz wire task, with the adaptive group (M = 7.06, SD = 1.14) receiving significantly more accuracy-focused training than the fixed group (M = 5.88, SD = 2.89), t (128) = 3.072, p = 0.003, 95% CI [0.422, 1.948], d = 0.54. On average, the number of accuracy-focused tasks received by participants was negatively correlated with experiences of success (i.e., the number of repetitions where the participant outperformed the primer; r (128) = −0.38, p < 0.001) and change in self-efficacy (r (128) = −0.24, p = 0.006), suggesting that accuracy-focused training (as opposed to speed-focused training) was more challenging and associated with lower confidence in one’s own skill. That said, the number of accuracy-focused tasks were not correlated with improved speed (virtual wire r (128) = −0.05, p = 0.57; transfer r (128) = −0.03, p = 0.70) or accuracy (virtual wire r (128) = −0.10, p = 0.26; transfer r (128) = 0.09, p = 0.32).

Training success. As described in the introduction, prior experiences of success are a key predictor of self-efficacy. Therefore, additional analyses were conducted to explore the role of outperforming the primer during training. On average, participants performed better than the primer on 7 out of 10 repetitions of the task (M = 6.95, SD = 2.19) with a Welch t-test suggesting no significant difference between adaptive (M = 6.75, SD = 1.29) and fixed training (M = 7.15, SD = 2.82), t (89.6) = −1.041, p = 0.301, 95% CI [−1.164, 0.364], d = −0.18. Furthermore, experiences of success (i.e., outperforming the primer) was positively associated with self-efficacy and improvements in performance inside but not outside IVR (see Table 3). Thus, frequently outperforming the primer was associated with gaining more self-efficacy from the virtual training as well as showing stronger improvements on a virtual wire, but not on a physical wire.

Training evaluation. Seven items were included after the post-test to measure participant evaluation of the fit between the training content and their needs (See Table 4 for individual items). Analyses were conducted based on the mean training evaluation score (M = 6.95, SD = 1.47), which demonstrated good internal reliability, as indicated by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83. Mean and standard deviations of individual items can be seen in Table 4. Correlational analysis indicated that training evaluation was positively associated with increases in self-efficacy (r (128) = 0.209, p = 0.017) and accuracy (r (128) = 0.176, p = 0.045). However, these correlations did not hold after Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons. Furthermore, training evaluation was not significantly different when comparing the adaptive (M = 7.01, p = 1.60) and fixed training (M = 6.89, p = 1.33), t(128) = 0.477, p = 0.634, 95% CI [−0.388, 0.634], d = 0.08.

5 Discussion

5.1 Adaptive virtual training

Kelley (1969) suggested that when done correctly, adaptive training should be more effective than fixed or non-adaptive training. However, results of the present study revealed no difference in terms of self-efficacy or improved performance either in- or outside IVR. While some prior research has found support for adaptive being more effective than non-adaptive training (Fricoteaux et al. 2014; Gray 2017; Lang et al. 2018; Zhang & Tsai 2021), the results of the present study aligns with those finding limited or no difference (Aguilar Reyes et al. 2023; Billings 2012; Serge et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2024). Two plausible interpretations of these mixed findings will be discussed below.

First, the mixed results can be due to differences in the used control group. Specifically, prior research generally compares adaptive training to non-adaptive (one-size-fits-all) training (e.g., Peretz et al. 2011), whereas the present study compared adaptive training with fixed training, thus further reducing the difference between conditions. In other words, both conditions included a degree of adaptability, meaning that the lack of difference between groups could be due to the increased adaptiveness being unnecessary. The fundamental adaptability of fixed training, where baseline measures of performance and self-efficacy were used to form the focus and difficulty of the training content, may be enough to ensure an adequate fit of training content without the need for the complex adaptive logic of the adaptive training. This interpretation is further supported by the fact that no differences were found in training difficulty between groups, suggesting that the added adaptiveness from adaptive training was not required to achieve a sufficient fit between trainee need and training content.

Second, the lack of difference could be a result of the chosen trainee behaviours, adaptive variables, or adaptive logic. When designing the adaptive logic, two adaptive variables (task focus and task difficulty) and two trainee behaviours (self-efficacy and performance) were used to adjust training content to the individual trainee. In terms of adaptive logic, participants received training focusing on the type of performance they felt the least confident in with the aim of improving confidence for said aspect of their own ability. Although this resulted in the adaptive training including significantly more accuracy-focused training, both groups primarily received accuracy-focused training in a relatively similar sequence. Interestingly, accuracy-focused training was generally more difficult, indicated by a negative correlation with training success. Furthermore, accuracy-focused feedback was provided by giving participants information every time they touched the wire (i.e., made a mistake) and only indirectly highlighted success in the form of completing the task without letting the red bar run out. Where prior research emphasises the importance of giving feedback during successful training (Abbas & North 2018; Saemi et al. 2012), the accuracy-focused training could have provided a too strong emphasis on making mistakes (the red bar getting smaller) at the cost of emphasis of success (completing without letting the bar run out). A solution for future research is to either flip the adaptive logic, thus allowing participants to receive the type of training they feel the most confident or successful in, or to adjust training content to include a clear focus on successfully improving in the type of task they feel the least confident in.

Generally, further research into appropriate selection of trainee behaviour and adaptive variables is needed to better understand their impact on training outcomes and their potential for adaptive training. This study focused specifically on self-efficacy and performance, which may limit the generalisbility of conclusions about adaptive training as a whole, since it is possible that a focus solely on performance or in other domains would yield different outcomes, such as in the case of Gray (2017) finding beneficial effects of adaptive training in a baseball setting. Where the present study focused on performance and self-efficacy as trainee behaviours, a fruitful direction for future research is the inclusion of feedback type and the result of adaptive feedback on self-efficacy. Since novel IVR-based technology are increasingly implementing eye-tracking or psychophysiological measures (ECG, EDA, etc.), another direction is to focus on the potential of utilising these for trainee behaviour. Lastly, the present study highlights the need for more controlled experiments with relatively large samples to further investigate when the higher requirements of implementing adaptive, rather than fixed, training can be expected to improve training outcomes.

5.2 Virtual training, performance, and skill transfer

Virtual training had a significant effect on performance both in- and outside IVR. Virtual training had a stronger effect on performance within the same virtual environment, as indicated by a medium effect size for performance on the virtual task (d = −0.41; d = −0.43) and only a small effect size for performance on the physical task (d = −0.25; d = 0.17). In accordance with prior research (Jensen & Konradsen 2018; Radhakrishnan et al. 2021), this suggests that while virtual training can have positive effects on performance outside IVR, the degree of skill transfer from the virtual environment to the real environment may vary and could potentially be less than the improvements seen in the virtual environment itself. However, this result may be particular to the buzz wire training scenario, which is a simplified task compared to many real-world skills. Future work could explore how virtual training can be modified to better represent complex real-world tasks, incorporating elements that have shown successful VR skill transfer in prior studies on teaching practical skills (Bhargava et al. 2018). Regardless, these findings provide valuable insight by highlighting the importance of carefully evaluating potential differences in performance when implementing virtual training for skills to be used in a physical setting.

Additionally, on the measure of skill transfer, virtual training only led to an increase in accuracy whereas the opposite was the case for speed, which decreased significantly as a result of training when measured using a physical version of the task. In other words, for one measure of performance, virtual training had the opposite effect on the virtual task as the physical version. This finding is in line with the study by Ragan et al. (2015), suggesting that performance in a simulation should not uncritically be assumed to reflect performance on a real version of the same task. Therefore, future research should be mindful of how performance is measured and whether it can be assumed to transfer from a virtual to a real environment. Like in the present study, including measures of the desired outcome variable in both settings offer great potential in terms of not only investigating skill transfer, but also gaining knowledge of the potential loss of performance when seeking to transfer the learned skill to the real world. Additionally, training programs using virtual training applications should likewise be mindful of trade-off, such as the value of strengthened engagement and repeatability versus potential loss of transfer.

5.3 The role of self-efficacy in training

The present study provides valuable insight into the role of self-efficacy in IVR-based training. Previous literature supports the central role of self-efficacy in predicting learning (Sitzmann & Ely 2011) and training outcomes (Gegenfurtner et al. 2014). However, while virtual training did increase performance in the present study, the opposite was true for self-efficacy, which was significantly lower after the virtual training.

As discussed in Sect. 4.1, it is possible that feedback of the accuracy-focused training had too much emphasis on highlighting mistakes (i.e., failure) rather than increased accuracy (i.e., success). As supported by prior research, it is crucial that feedback focus on training success (i.e., positive feedback), which is associated with higher increases in self-efficacy (Abbas & North 2018; Saemi et al. 2012). This interpretation is further supported by the fact that receiving more accuracy-focused training was negatively associated with self-efficacy in the present study. Thus, further research should carefully consider ways to adjust training content while either controlling for feedback type or focusing on positive feedback with the aim of supporting trainee self-efficacy.

Alternatively, the decrease in self-efficacy was likely due to participants overestimating their own ability during the initial measure. Following by Bandura’s (2006) recommendations, self-efficacy was measured before the behaviour of interest (i.e., before completing the real buzz wire task). To give participants a frame of reference when filling the SE items without receiving training on the task, participants were asked to simply move the loop from one end of the wire to the other at the very beginning of the experiment. This simplified familiarisation task, however, may have inadvertently contributed to the Dunning-Kruger effect (Kruger & Dunning 1999), leading participants to overestimate their skills.

However, one explanation of the decrease in self-efficacy is that this familiarisation task led to an overestimation of one’s own skill whereafter the real task was experienced as significantly more difficult. While it should be noted that dynamic self-efficacy was measured using fewer and differently phrased items, this would also offer some explanation to the results of exploratory analyses of dynamic changes in self-efficacy, showing a general increase in self-efficacy for both speed and accuracy when measured throughout the virtual training. The contradictory finding emphasises the need for considering multiple measures of concepts such as self-efficacy, as well as including dynamic measures when possible. Additionally, the dynamic measure showed an inverse relationship between self-efficacy for speed and accuracy. While this could be a result of participants aiming to optimise performance on one of the two types of performance, further research is needed to explore the relationship between dynamic changes in self-efficacy and their link to performance.

5.4 Limitations

A strength of the present study is the inclusion of measures of performance on a virtual and physical version of the task of interest. This provides valuable insight in the potential loss of training outcomes when transferring from a virtual to a physical setting. However, it is important to acknowledge that the buzz wire task used in this study is a highly simplified motor skill task without immediate practical benefits or cognitive elements such as procedural knowledge or decision-making. This type of transfer reflects what is referred to as near transfer, meaning transfer of skill between two tasks that are relatively similar (Barak et al. 2016). While focusing on near transfer is valuable for isolating the loss of training outcomes when transferring a skill from a virtual to a physical setting, it limits the generalisability findings to more complex, real-world tasks. Future research should explore far transfer, meaning the transfer of skill between different tasks or contexts (Barak et al. 2016). For example, while fine motor skills training with the buzz wire has been studied for in contexts such as surgery training (Mariani et al. 2020), further research could investigate the far transfer and the effects of such training on practical applications requiring similar hand–eye coordination and fine motor control. Alternatively, modified versions of the buzz wire task could be developed to incorporate cognitive elements, such as requiring participants to follow specific procedures or make decisions based on visual cues during training. Another potential limitation of the buzzwire task setup is related to the nature of the sensation felt through the controllers when the loop touches the wire in the VR simulation. The present study uses vibratory feedback through the Oculus controllers. However, more realistic haptic feedback techniques, such as kinesthetic (robotic touch) feedback, should be explored in future studies.

A hallmark of training is that improvements in skill persist over time. Although other studies have found support for retention as a result of similar, short-term training sessions (Radhakrishnan et al. 2021), the experimental design of the present study lacked a retention test to further investigate such a claim. Thus, although the present study found support for enhanced performance, especially in a virtual setting but also in a physical setting, future studies would benefit from including retention tests when possible.

Lastly, it should be noted that the measures of pre- and post-test self-efficacy and dynamic self-efficacy were not identical. In the former, six items were used based on prior research, whereas the latter consisted of two items, which referred to confidence in completing the specific task quickly or accurately. The primary interest for statistical analysis was on the full scale, whereas dynamic self-efficacy was primarily used to inform the adaptive logic of the system. Thus, while the dynamic reports of self-efficacy offer insight into the changing perspective of the user, it is important to emphasise that the full scale offers a higher-quality measure of the concept.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of the present study suggest that immersive virtual reality (IVR) is an effective tool when aiming to support fine motor skill training, supported by an increased performance as a result of virtual training. The study departs from prior research by conducting a preregistered, controlled experiment with a relatively large sample size and by investigating the potential of implementing continuous measures of psychological concepts (self-efficacy) to adjust training content.

The results did not reveal any difference between fixed and adaptive virtual training, suggesting that the added complexity of adaptive training may be unnecessary in some cases. While this is consistent with prior research comparing fixed and adaptive training (Zahabi & Abdul Razak 2020), further research is needed to explore when the complexity of adaptive training can be fully utilised to optimise training outcomes.

An important strength of the study was the inclusion of performance measures both in- and outside IVR coupled with the finding that IVR-based training had a stronger effect when performance was measured in a virtual rather than physical setting. As such, the results provide valuable insights into the importance of the context by suggesting that a loss of training outcomes should be expected when transferring from a virtual to a physical environment. Building on prior suggestions, this finding underscores the need for future research to design studies that factor in and further investigate the role of IVR-based training on performance in both virtual and physical environments.

Data availability

All data analysed during the current study and the preregistration are available on OSF (https://osf.io/jmg9t/).

References

Abbas Z-A, North JS (2018) Good-vs. poor-trial feedback in motor learning: the role of self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation across levels of task difficulty. Learn Instr 55:105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.09.009

Abich J IV, Parker J, Murphy JS, Eudy M (2021) A review of the evidence for training effectiveness with virtual reality technology. Virtual Reality 25(4):919–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-020-00498-8

Aguilar Reyes CI, Wozniak D, Ham A, Zahabi M (2023) Design and evaluation of an adaptive virtual reality training system. Virtual Reality 27(3):2509–2528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-023-00827-7

Bandura A (1977) Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 84(2):191

Bandura A (2006) Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. Self-Efficacy Beliefs Adolesc 5(1):307–337

Bandura A (1997) Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. Macmillan.

Barak M, Hussein-Farraj R, Dori YJ (2016) On-campus or online: examining self-regulation and cognitive transfer skills in different learning settings. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 13(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-016-0035-9

Bertrand J, Bhargava A, Madathil KC, Gramopadhye A, Babu SV (2017) The effects of presentation method and simulation fidelity on psychomotor education in a bimanual metrology training simulation. In: 2017 IEEE symposium on 3D user interfaces (3DUI), https://doi.org/10.1109/3DUI.2017.7893318

Bhargava A, Bertrand JW, Gramopadhye AK, Madathil KC, Babu SV (2018) Evaluating multiple levels of an interaction fidelity continuum on performance and learning in near-field training simulations. IEEE Trans Visual Comput Graphics 24(4):1418–1427. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2018.2794639

Billings D (2012) Efficacy of adaptive feedback strategies in simulation-based training. Mil Psychol 24(2):114–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2012.672905

Borst CW, Lipari NG, Woodworth JW (2018) Teacher-guided educational vr: assessment of live and prerecorded teachers guiding virtual field trips. In: 2018 IEEE conference on virtual reality and 3D user interfaces (VR),

Butt AL, Kardong-Edgren S, Ellertson A (2018) Using game-based virtual reality with haptics for skill acquisition. Clin Simul Nurs 16:25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2017.09.010

Buttussi F, Chittaro L (2017) Effects of different types of virtual reality display on presence and learning in a safety training scenario. IEEE Trans Visual Comput Graphics 24(2):1063–1076. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2017.2653117

Chauvel G, Wulf G, Maquestiaux F (2015) Visual illusions can facilitate sport skill learning. Psychon Bull Rev 22:717–721. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-014-0744-9

Checa D, Bustillo A (2020) A review of immersive virtual reality serious games to enhance learning and training. Multimed Tools Appl 79(9):5501–5527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-019-08348-9

Chiossi F, Welsch R, Villa S, Chuang L, Mayer S (2022) Virtual reality adaptation using electrodermal activity to support the user experience. Big Data Cognit Comput 6(2):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc6020055

Cho H-C, Abe S (2013) Is two-tailed testing for directional research hypotheses tests legitimate? J Bus Res 66(9):1261–1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.02.023

Coban M, Bolat YI, Goksu I (2022) The potential of immersive virtual reality to enhance learning: a meta-analysis. Educ Res Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100452

Cooper N, Millela F, Cant I, White MD, Meyer G (2021) Transfer of training—virtual reality training with augmented multisensory cues improves user experience during training and task performance in the real world. PLoS ONE 16(3):e0248225. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248225

de Lima ES, Silva BM, Galam GT (2022) Adaptive virtual reality horror games based on machine learning and player modeling. Entertain Comput 43:100515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2022.100515

Ding D, Brinkman W-P, Neerincx MA (2020) Simulated thoughts in virtual reality for negotiation training enhance self-efficacy and knowledge. Int J Hum Comput Stud 139:102400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2020.102400

Drey T, Jansen P, Fischbach F, Frommel J, Rukzio E (2020) Towards progress assessment for adaptive hints in educational virtual reality games. Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems. https://doi.org/10.1145/3334480.3382789

El-Sabagh HA (2021) Adaptive e-learning environment based on learning styles and its impact on development students’ engagement. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 18(1):53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00289-4

Feltz DL, Chow GM, Hepler TJ (2008) Path analysis of self-efficacy and diving performance revisited. J Sport Exerc Psychol 30(3):401–411. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.30.3.401

Feng Z, González VA, Amor R, Lovreglio R, Cabrera-Guerrero G (2018) Immersive virtual reality serious games for evacuation training and research: a systematic literature review. Comput Educ 127:252–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.09.002

Frederiksen JG, Sørensen SMD, Konge L, Svendsen MBS, Nobel-Jørgensen M, Bjerrum F, Andersen SAW (2020) Cognitive load and performance in immersive virtual reality versus conventional virtual reality simulation training of laparoscopic surgery: a randomized trial. Surg Endosc 34:1244–1252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-06887-8

Fricoteaux L, Thouvenin I, Mestre D (2014) GULLIVER: a decision-making system based on user observation for an adaptive training in informed virtual environments. Eng Appl Artif Intell 33:47–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2014.03.005

Gegenfurtner A, Veermans K, Vauras M (2013) Effects of computer support, collaboration, and time lag on performance self-efficacy and transfer of training: a longitudinal meta-analysis. Educ Res Rev 8:75–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2012.04.001

Gegenfurtner A, Quesada-Pallarès C, Knogler M (2014) Digital simulation-based training: a meta-analysis. Br J Edu Technol 45(6):1097–1114. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12188

Gerbaud S, Gouranton V, Arnaldi B (2009) Adaptation in collaborative virtual environments for training. Learning by Playing. Game-based education system design and development: 4th international conference on E-Learning and Games, Edutainment 2009, Banff, Canada, August 9–11, 2009. Proceedings 4, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-03364-3_40

Gray R (2017) Transfer of training from virtual to real baseball batting. Front Psychol 8:2183. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02183

Hamilton D, McKechnie J, Edgerton E, Wilson C (2021) Immersive virtual reality as a pedagogical tool in education: a systematic literature review of quantitative learning outcomes and experimental design. J Comput Educ 8(1):1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-020-00169-2

Harvey C, Selmanović E, O’Connor J, Chahin M (2021) A comparison between expert and beginner learning for motor skill development in a virtual reality serious game. Vis Comput 37(1):3–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00371-019-01702-w

Hooper J, Tsiridis E, Feng JE, Schwarzkopf R, Waren D, Long WJ, Poultsides L, Macaulay W, Papagiannakis G, Kenanidis E (2019) Virtual reality simulation facilitates resident training in total hip arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 34(10):2278–2283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2019.04.002

Huang Y, Richter E, Kleickmann T, Richter D (2022) Comparing video and virtual reality as tools for fostering interest and self-efficacy in classroom management: results of a pre-registered experiment. Br J Edu Technol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13254

Huber T, Wunderling T, Paschold M, Lang H, Kneist W, Hansen C (2018) Highly immersive virtual reality laparoscopy simulation: development and future aspects. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg 13:281–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11548-017-1686-2

Hutchinson JC, Sherman T, Martinovic N, Tenenbaum G (2008) The effect of manipulated self-efficacy on perceived and sustained effort. J Appl Sport Psychol 20(4):457–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200802351151

Iván Aguilar Reyes C, Wozniak D, Ham A, Zahabi M (2022) An adaptive virtual reality-based training system for pilots. Proc Human Factors Ergon Soc Ann Meet. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071181322661063

Jain S, Lee S, Barber SR, Chang EH, Son Y-J (2020) Virtual reality based hybrid simulation for functional endoscopic sinus surgery. IISE Trans Healthcare Syst Eng 10(2):127–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/24725579.2019.1692263

Jensen L, Konradsen F (2018) A review of the use of virtual reality head-mounted displays in education and training. Educ Inf Technol 23(4):1515–1529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9676-0

Kelley CR (1969) What is adaptive training? Hum Factors 11(6):547–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872086901100602

Klingenberg S, Jørgensen ML, Dandanell G, Skriver K, Mottelson A, Makransky G (2020) Investigating the effect of teaching as a generative learning strategy when learning through desktop and immersive VR: a media and methods experiment. Br J Edu Technol 51(6):2115–2138. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13029

Klock ACT, Gasparini I, Pimenta MS, Hamari J (2020) Tailored gamification: a review of literature. Int J Hum Comput Stud 144:102495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2020.102495

Koumaditis K, Chinello F, Mitkidis P, Karg S (2020) Effectiveness of virtual versus physical training: the case of assembly tasks, trainer’s verbal assistance, and task complexity. IEEE Comput Graphics Appl 40(5):41–56. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCG.2020.3006330

Kruger J, Dunning D (1999) Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol 77(6):1121. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

Lang Y, Wei L, Xu F, Zhao Y, Yu L-F (2018) Synthesizing personalized training programs for improving driving habits via virtual reality. In: 2018 IEEE conference on virtual reality and 3D user interfaces (VR), https://doi.org/10.1109/VR.2018.8448290

Lee PQ, Rajendran V, Mombaur K (2022) Optimization-based motion generation for buzzwire tasks with the REEM-C humanoid robot. Front Robot AI 9:898890. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2022.898890

Lehikko A (2021) Measuring self-efficacy in immersive virtual learning environments: a systematic literature review. J Interact Learn Res 32(2):125–146

Levac DE, Huber ME, Sternad D (2019) Learning and transfer of complex motor skills in virtual reality: a perspective review. J Neuroeng Rehabil 16:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-019-0587-8

Liu ZM, Fan X, Liu Y, Ye X, d. (2022) Effects of immersive virtual reality cardiopulmonary resuscitation training on prospective kindergarten teachers’ learning achievements, attitudes and self-efficacy. Br J Edu Technol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13237

Lui LF, Radhakrishnan U, Chinello F, Koumaditis K (2023) Adaptive immersive VR training based on performance and self-efficacy. In: 2023 IEEE conference on virtual reality and 3D user interfaces abstracts and workshops (VRW), https://doi.org/10.1109/VRW58643.2023.00012

Ma M, Bechkoum K (2008) Serious games for movement therapy after stroke. In: 2008 IEEE international conference on systems, man and cybernetics. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSMC.2008.4811562

Makransky G, Petersen GB (2021) The cognitive affective model of immersive learning (CAMIL): a theoretical research-based model of learning in immersive virtual reality. Educ Psychol Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09586-2

Makransky G, Borre-Gude S, Mayer RE (2019) Motivational and cognitive benefits of training in immersive virtual reality based on multiple assessments. J Comput Assist Learn 35(6):691–707. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12375

Mariani A, Pellegrini E, De Momi E (2020) Skill-oriented and performance-driven adaptive curricula for training in robot-assisted surgery using simulators: a feasibility study. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 68(2):685–694. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2020.3011867

Marougkas A, Troussas C, Krouska A, Sgouropoulou C (2023) How personalized and effective is immersive virtual reality in education?. a systematic literature review for the last decade. Multimed Tools Appl. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-15986-7

Moritz SE, Feltz DL, Fahrbach KR, Mack DE (2000) The relation of self-efficacy measures to sport performance: a meta-analytic review. Res Q Exerc Sport 71(3):280–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2000.10608908

Mousavi SM, Iwatsuki T (2021) Easy task and choice: motivational interventions facilitate motor skill learning in children. J Motor Learn Dev 10(1):61–75. https://doi.org/10.1123/jmld.2021-0023

Muñoz JE, Pope AT, Velez LE (2016) Integrating biocybernetic adaptation in virtual reality training concentration and calmness in target shooting. In Physiological computing systems (pp. 218–237). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27950-9_12

Murcia-López M, Steed A (2018) A comparison of virtual and physical training transfer of bimanual assembly tasks. IEEE Trans Visual Comput Graphics 24(4):1574–1583. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2018.2793638

Oagaz H, Schoun B, Choi M-H (2022) Real-time posture feedback for effective motor learning in table tennis in virtual reality. Int J Hum Comput Stud 158:102731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2021.102731

Ong NT, Lohse KR, Hodges NJ (2015) Manipulating target size influences perceptions of success when learning a dart-throwing skill but does not impact retention. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01378

Pascua LA, Wulf G, Lewthwaite R (2015) Additive benefits of external focus and enhanced performance expectancy for motor learning. J Sports Sci 33(1):58–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.922693

Peretz C, Korczyn AD, Shatil E, Aharonson V, Birnboim S, Giladi N (2011) Computer-based, personalized cognitive training versus classical computer games: a randomized double-blind prospective trial of cognitive stimulation. Neuroepidemiology 36(2):91–99. https://doi.org/10.1159/000323950

Pulijala Y, Ma M, Pears M, Peebles D, Ayoub A (2018) Effectiveness of immersive virtual reality in surgical training—a randomized control trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 76(5):1065–1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2017.10.002

Radhakrishnan U, Koumaditis K, Chinello F (2021) A systematic review of immersive virtual reality for industrial skills training. Behav Inf Technol 40(12):1310–1339. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2021.1954693

Radhakrishnan U, Chinello F, Koumaditis K (2023a) Investigating the effectiveness of immersive VR skill training and its link to physiological arousal. Virtual Reality 27(2):1091–1115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-022-00699-3

Radhakrishnan U, Kuang L, Koumaditis K, Chinello F, Pacchierotti C (2023) Haptic feedback, performance and arousal. a comparison study in an immersive VR motor skill training task. IEEE Trans Haptics. https://doi.org/10.1109/TOH.2023.3319034

Ragan ED, Bowman DA, Kopper R, Stinson C, Scerbo S, McMahan RP (2015) Effects of field of view and visual complexity on virtual reality training effectiveness for a visual scanning task. IEEE Trans Visual Comput Graphics 21(7):794–807. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2015.2403312

Rosenqvist O, Skans ON (2015) Confidence enhanced performance?–the causal effects of success on future performance in professional golf tournaments. J Econ Behav Organ 117:281–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2015.06.020

Ruxton GD, Neuhäuser M (2010) When should we use one-tailed hypothesis testing? Methods Ecol Evol 1(2):114–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2010.00014.x

Saemi E, Porter JM, Ghotbi-Varzaneh A, Zarghami M, Maleki F (2012) Knowledge of results after relatively good trials enhances self-efficacy and motor learning. Psychol Sport Exerc 13(4):378–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.12.008

Schunk DH, DiBenedetto MK (2016) Self-efficacy theory in education. In: Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 34–54). Routledge.

Serge SR, Priest HA, Durlach PJ, Johnson CI (2013) The effects of static and adaptive performance feedback in game-based training. Comput Hum Behav 29(3):1150–1158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.007

Shakur SF, Luciano CJ, Kania P, Roitberg BZ, Banerjee PP, Slavin KV, Sorenson J, Charbel FT, Alaraj A (2015) Usefulness of a virtual reality percutaneous trigeminal rhizotomy simulator in neurosurgical training. Op Neurosurg 11(3):420–425. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0000000000000853

Shu Y, Huang Y-Z, Chang S-H, Chen M-Y (2019) Do virtual reality head-mounted displays make a difference? A comparison of presence and self-efficacy between head-mounted displays and desktop computer-facilitated virtual environments. Virtual Reality 23(4):437–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-018-0376-x

Sitzmann T, Ely K (2011) A meta-analysis of self-regulated learning in work-related training and educational attainment: what we know and where we need to go. Psychol Bull 137(3):421. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022777

Song H, Kim T, Kim J, Ahn D, Kang Y (2021) Effectiveness of VR crane training with head-mounted display: Double mediation of presence and perceived usefulness. Autom Constr 122:103506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103506

Sportillo D, Avveduto G, Tecchia F, Carrozzino M (2015) Training in VR: a preliminary study on learning assembly/disassembly sequences. Augmented and virtual reality: second international conference, AVR 2015, Lecce, Italy, August 31-September 3, 2015, Proceedings 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22888-4_24

Stevens D, Anderson DI, O’Dwyer NJ, Williams AM (2012) Does self-efficacy mediate transfer effects in the learning of easy and difficult motor skills? Conscious Cogn 21(3):1122–1128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2012.03.014

Ulmer J, Braun S, Cheng C-T, Dowey S, Wollert J (2022) Gamification of virtual reality assembly training: effects of a combined point and level system on motivation and training results. Int J Hum Comput Stud 165:102854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2022.102854

Vaughan N, Gabrys B, Dubey VN (2016) An overview of self-adaptive technologies within virtual reality training. Comput Sci Rev 22:65–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosrev.2016.09.001

Verniani A, Galvin E, Tredinnick S, Putman E, Vance EA, Clark TK, Anderson AP (2024) Features of adaptive training algorithms for improved complex skill acquisition. Front Virtual Reality. https://doi.org/10.3389/frvir.2024.1322656

Wang L, Du S, Liu H, Yu J, Cheng S, Xie P (2017) A virtual rehabilitation system based on EEG-EMG feedback control. In: 2017 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), https://doi.org/10.1109/CAC.2017.8243542

Wang L, Huang M, Liu J, Xiao S, Yang R (2024) Design and evaluation of a self-adaptive strategy for movement modulation in virtual rehabilitation. In: 2024 16th International Conference on Human System Interaction (HSI). https://doi.org/10.1109/HSI61632.2024.10613573

Wei X, Lin L, Meng N, Tan W, Kong S-C (2021) The effectiveness of partial pair programming on elementary school students’ computational thinking skills and self-efficacy. Comput Educ 160:104023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104023

Winther F, Ravindran L, Svendsen KP, Feuchtner T (2020) Design and evaluation of a vr training simulation for pump maintenance based on a use case at grundfos. In: 2020 IEEE conference on virtual reality and 3D user interfaces (VR), https://doi.org/10.1109/VR46266.2020.00097

Wulf G, Lewthwaite R (2016) Optimizing performance through intrinsic motivation and attention for learning: the OPTIMAL theory of motor learning. Psychon Bull Rev 23:1382–1414. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-015-0999-9

Wulf G, Chiviacowsky S, Cardozo PL (2014) Additive benefits of autonomy support and enhanced expectancies for motor learning. Hum Mov Sci 37:12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2014.06.004