Abstract

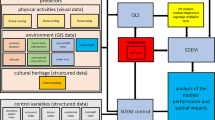

The current literature often values intangible goods like cultural heritage by applying stated preference methods. In recent years, however, the increasing availability of large databases on real estate transactions and listed prices has opened up new research possibilities and has reduced various existing barriers to applications of conventional (spatial) hedonic analysis to the real estate market. The present paper provides one of the first applications using a spatial autoregressive model to investigate the impact of cultural heritage—in particular, listed buildings and historic–cultural sites (or historic landmarks)—on the value of real estate in cities. In addition, this paper suggests a novel way of specifying the spatial weight matrix—only prices of sold houses influence current price—in identifying the spatial dependency effects between sold properties. The empirical application in the present study concerns the Dutch urban area of Zaanstad, a historic area for which over a long period of more than 20 years detailed information on individual dwellings, and their market prices are available in a GIS context. In this paper, the effect of cultural heritage is analysed in three complementary ways. First, we measure the effect of a listed building on its market price in the relevant area concerned. Secondly, we investigate the value that listed heritage has on nearby property. And finally, we estimate the effect of historic–cultural sites on real estate prices. We find that, to purchase a listed building, buyers are willing to pay an additional 26.9 %, while surrounding houses are worth an extra 0.28 % for each additional listed building within a 50-m radius. Houses sold within a conservation area appear to gain a premium of 26.4 % which confirms the existence of a ‘historic ensemble’ effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In British English, historic buildings which are part of the cultural heritage are called ‘Listed Buildings’ (grades I, II and III), which includes houses of architectural merit. In American English, the equivalent is ‘landmark’ for all types of historic buildings.

Dutch heritage (In Dutch: Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed) is the government organization which determines which heritage should be listed.

In the Netherlands, 65–70 % of all houses are sold by an NVM real estate agent.

The density for various distances was calculated (0–50, 50–100, 100–150 and 150–200 m) and was used as variables in the regression. The results indicated that beyond 50 m, the effect of listed heritage is negligible and insignificant.

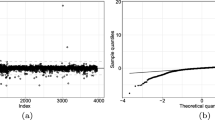

OLS is easy to interpret and the results can be used to check for spatial dependence.

To correct for this segmented market effect, we have created an own price index by using the year dummies of the simple OLS. In this way, we have corrected for the year effects.

Different radius specifications were tested, but our results make it plausible to choose a relatively steep distance decay.

The correlation between the heritage density and the conservation area is high with a value of 0.69.

Spatial models have a more complicated interpretation than parameters of a linear regression. OLS allows a straightforward interpretation as the partial derivatives of the dependent variable with respect to the explanatory variable. Won Kim et al. (2003) have proved that with a spatial lag in the model, the outcome of the parameter estimates should be interpreted with care and that when the weight matrix is row standardized, the parameter outcomes multiplication with the multiplier is needed: \( \frac{1}{1 - \rho } \).

Abreu et al. (2004), Pace and LeSage (2006) and LeSage and Pace (2009) show that this interpretation should be elaborated. In this paper, we follow the terminology of LeSage and Pace (2009). Their partial derivative interpretation leads to an average direct impact, an average indirect impact and an average total impact. This is a more valid basis for testing hypotheses as they show with an example where the estimated coefficient is negative and insignificant but the spatial impact is positive and significant.

Apparently, there is some negative correlation between the monument density/ha at a 50-metre radius and the listed heritage dummy.

References

Abreu M, de Groot HLF, Florax RJGM (2004) Space and growth: a survey of empirical evidence and methods. Working Paper TI 04-129/3. Tinbergen Institute, Amsterdam

Ahlfeldt GM, Waennig W (2010) Substitutability and complementarity of urban amenities: external effects of built heritage in Berlin. Real Estate Econ 38(2):285–323

Anselin L (1988) Spatial econometrics: methods and models. Kluwer, Dordrecht

Anselin L (2006) Spatial econometrics. In: Mills T, Patterson K (eds) Palgrave handbook of econometrics, vol 1., Econometric theoryPalgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, pp 901–969

Anselin L (2010) Thirty years of spatial econometrics. Pap Reg Sci 89(1):3–25

Asabere PK, Huffman FE (1994) Historic designation and residential market values. Apprais J 62(1):396–401

Asabere PK, Huffman FE, Mehdian S (1994) The adverse impacts of local historic designation: the case of small apartment buildings in Philadelphia. J Real Estate Financ Econ 8(2):225–234

Baranzini A, Ramirex J, Schaerer C, Thalmann P (eds) (2008) Hedonic methods in housing markets: pricing environmental amenities and segregation. Springer, Berlin

Basu S, Thibodeau FG (1998) Analysis of spatial autocorrelation in house prices. J Real Estate Financ Econ 17(1):61–85

Bitter C, Mulligan G, Dall’erba S (2007) Incorporating spatial variation in housing attribute prices: a comparison of geographically weighted regression and the spatial expansion method. J Geogr Syst 9(1):7–27

Brasington DM, Hite D (2005) Demand for environmental quality: a spatial hedonic analysis. Reg Sci Urban Econ 35(1):57–82

Brueckner JK, Thisse JF, Zenou Y (1999) Why is Central Paris rich and downtown Detroit poor? An Amenity-based theory. Eur Econ Rev 43(1):91–107

Can A (1992) Specification and estimation of hedonic housing price models. Reg Sci Urban Econ 22(3):453–474

Coulson NE, Lahr ML (2005) Gracing the Land of Elvis and Beale Street: historic designation and property values in Memphis. Real Estate Econ 33(3):487–508

Coulson NE, Leichenko RM (2001) The internal and external impact of historical designation on property values. J Real Estate Financ Econ 23(2):113–124

de Vries J, van der Woude AM (1997) The first modern economy: success, failure, and perseverance of the Dutch economy, 1500–1815. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Deodhar V (2004) Does the housing market value heritage? Some empirical evidence, research paper no. 403, Macquarie University, Sydney

Ekeland I, Heckman J, Nesheim L (2002) Identifying hedonic models. Am Econ Rev 92(2):304–309

Elhorst JP (2010) Applied spatial econometrics: raising the bar. Spatial Econ Anal 5(1):9–28

Florax R, de Graaff T (2004) The performance of diagnostic tests for spatial autocorrelation in linear regression models: a meta-analysis of simulation studies. In: Anselin L, Florax R, Rey SJ (eds) Advances in spatial econometrics: methodology, tools and applications. Springer, Berlin, pp 29–65

Florax RJGM, Folmer H, Rey SJ (2003) Specification searches in spatial econometrics: the relevance of Hendry’s methodology. Reg Sci Urban Econom 33(3):557–579

Ford DA (1989) The effect of historic district designation on single-family home prices. Real Estate Econ 17(2):353–362

Fusco Girard L, Nijkamp P (eds) (2009) Cultural tourism and sustainable local development. Ashgate, Aldershot

Glaeser EL, Kolko J, Saiz A (2001) Consumer City. J Econ Geogr 1(1):27–50

Goodman AC, Thibodeau TG (2003) Housing market segmentation and hedonic prediction accuracy. J Hous Econ 12(2):181–201

Gorman WM (1956) A possible procedure for analysing quality differentials in the eggs market. Rev Econ Stud 47:843–856

Koschinsky J, Lozano-Gracia N, Piras G (2011) The welfare benefit of a home’s location: an empirical comparison of spatial and non-spatial model estimates. J Geogr Syst 1(1):1–38

Lancaster KJ (1966) A new approach to consumer theory. J Polit Econ 74(2):132–157

Lancaster KJ (1979) Author variety, equity, and efficiency: product variety in an industrial society. Columbia University Press, New York

Leichenko RM, Coulson NE, Listokin D (2001) Historic preservation and residential property values: an analysis of Texas cities. Urban Stud 38(9):1973–1987

LeSage JP, Pace RK (2009) Introduction to spatial econometrics. Chapman and Hall, London

LeSage JP, Pace RK (2012) the biggest myth in spatial econometrics. http://www.wu.ac.at/wgi/en/file_inventory/lesage20120110. Accessed 06 Jun 2012

Malpezzi S (2003) Hedonic pricing models: a selective and applied review. In: O’Sullivan T, Gibb K (eds) Housing economics and public policy. Blackwell Science Ltd, Oxford, pp 67–89

Mur J, Angulo A (2009) Model selection strategies in a spatial setting: some additional results. Reg Sci Urban Econ 39:200–213

Narwold A, Sandy J, Tu C (2008) Historic designation and residential property values. Int Real Estate Rev 11(1):83–95

Navrud S, Ready RC (2002) Valuing cultural heritage: applying environmental valuation techniques to historic buildings, monuments and artifacts. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Noonan DS (2003) Contingent valuation and cultural resources: a meta-analytic review of the literature. J Cult Econ 27(2):159–176

Noonan DS (2007) Finding an impact of preservation policies: price effects of historic landmarks on attached homes in Chicago, 1990–1999. Econ Dev Q 21(1):17–33

Noonan DS, Krupka DJ (2010) Determinants of historic and cultural landmark designation: why we preserve what we preserve. J Cult Econ 34(1):1–26

Noonan DS, Krupka DJ (2011) Making—or picking—winners: evidence of internal and external price effects in historic preservation policies. Real Estate Econ 39(2):379–407

Pace RK, LeSage JP (2006) Interpreting spatial econometric models. Paper presented at the regional science association international North American meetings, Toronto, Ontario

Palmquist RB, Smith VK (2003) The use of hedonic property value techniques for policy and litigation. In: Tietenberg T, Folmer H (eds) The international yearbook of environmental and resource economics 2002/2003. Edard Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 115–164

Rosen S (1974) Hedonic prices and implicit markets: product differentiation in pure competition. J Polit Econ 82(1):34–55

Ruijgrok ECM (2006) The three economic values of cultural heritage: a case study in The Netherlands. J Cult Herit 7(2):206–213

Schaeffer PV, Millerick CA (1991) The impact of historic district designation on property values: an empirical study. Econ Dev Q 5:301–312

Sheppard S (1999) Hedonic analysis of housing markets. In: Mills ES, Cheshire P (eds) Handbook of regional and urban economics, vol 3. North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp 1595–1635

Snowball JD (2008) Measuring the value of culture: methods and examples in cultural economics. Springer, Berlin

Sopranzetti BJ (2010) Hedonic regression analysis in real estate markets: a primer. In: Lee CF, Lee CA, Lee J (eds) Handbook of quantitative finance and risk management. Springer, Berlin, pp 1201–1207

Taylor LO (2003) The hedonic method. In: Champ PA, Boyle KJ, Brown TC (eds) A primer on non market valuation. Kluwer, Dordrecht, pp 331–393

Throsby D (2001) Economics and culture. Cambridge University Press, New York

Tobler WR (1970) A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Econ Geogr 46(2):234–240

Won Kim C, Phipps TT, Anselin T (2003) Measuring the benefits of air quality improvement: a spatial hedonic approach. J Environ Econ Manag 45(1):24–39

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Dutch Association of Real Estate Brokers (NVM) for making available their data on house transactions for this study. Furthermore, we thank the Land Registration Office (Kadaster) for providing complete data on the heritage status. This paper was written in the context of the CLUE cultural heritage research programme at the VU University Amsterdam, and the NICIS project on the ‘Economic valuation of cultural heritage’. The authors would like to thank James LeSage along with two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lazrak, F., Nijkamp, P., Rietveld, P. et al. The market value of cultural heritage in urban areas: an application of spatial hedonic pricing. J Geogr Syst 16, 89–114 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10109-013-0188-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10109-013-0188-1

Keywords

- Cultural heritage

- Listed building

- Valuation methods

- Stated preference methods

- Hedonic prices

- Spatial statistics

- Spatial autocorrelation

- Historic buildings