Abstract

In the history of genetics, the information-theoretical description of the gene, beginning in the early 1960s, had a significant effect on the concept of the gene. “Information” is a highly complex metaphor which is applicable in view of the description of substances, processes, and spatio-temporal organisation. Thus, information can be understood as a functional particle of many different language games (some of them belonging to subdisciplines of genetics, as the biochemical language game, some of them belonging to linguistics and informatics). It is this wide covering of different language games that justifies the common description of genes x, y, z as containing information for the phenotypic traits X, Y, Z (or the genome as storage for the information of a whole organism). However, if information is taken as the explanans and phenotypic traits or organisms as the explananda, then a description of the explanandum is of prior importance before the explanans can be characterised. This way of thinking could be useful for future discussions on the strikingly dominant “information”-metaphor, and the different gene concepts as well. The article illustrates this in two steps. First, a condensed overview on the history of genetics is given, which can be divided into three parts: (1) genetics without genes, (2) genetics with genes, but without information, (3) genetics with genes and information. It is assumed that this provides not only some historical knowledge about the origin of genetics and the introduction of technical terms, but offers at least preliminary insight into the methodological structure of genetic descriptions. In a second step, we redraw Spemann’s disturbation experiments to discuss our thesis that “genetic information” is not a natural entity, but part of a causality-language game which is secondarily added to the descriptions of interventionalistic practices, viz. experimental approaches.

Zusammenfassung

In der Genetik wird die Bedeutung des Informationsbegriffes (bzw. der aus den Informationswissenschaften entlehnten Metaphern) häufig als kontextabhängig eingeschätzt, ebenso wie der Begriff des Gens selbst. Die Rede von “genetischer Information”, wie sie seit den 1960er Jahren üblich ist, wird im vorliegenden Text unter überwiegend sprachkritischem Aspekt neu untersucht. Hier zeigt sich, dass die Dominanz der Informationsmetapher mit ihrer Vielschichtigkeit zusammenhängt, welche eine Anwendbarkeit auf vielen Ebenen, genauer gesagt, in verschiedenen Sprachspielen erlaubt. Gezeigt wird dies für Sprachspiele, mit deren spezifischem Vokabular die Genexpression beschrieben wird, z.B. dem Sprachspiel der Biochemie, der Zytologie, der Morphologie, oder auch Text- und Informationssprachspielen (in denen Begriffe wie Translation und Transkription zur Anwendung kommen). Diese Sprachspiele lassen sich als Sub-Sprachspiele eines Genetik-Metasprachspieles bezeichnen. Statt der Rede über Kontexte bietet sich also eine Analyse der betreffenden Sub-Sprachspiele an, um die Reichweite der Informationsmetapher direkt an der Struktur der Beschreibungen genetischer Effekte aufzuzeigen. Hierbei zeigt sich, dass “Information” als Explanans fungiert, und zwar für Proteine oder Phänotypen. Es wird argumentiert, dass die Verortung der Informationsmetapher als Explanans erst nach einer genauen Darstellung des Explanandum möglich ist. Exemplarisch wird dies zunächst anhand einer methodischen Rekonstruktion der genetischen Wissenschaften aufgezeigt, die hierzu in drei Phasen unterteilt werden: (1) Genetik ohne Gene, (2) Genetik mit Genen, aber ohne Information, (3) Genetik mit Genen und mit Information. Die Veränderung des Genbegiffes durch Zusammenführung mit der Informationsmetapher wird erörtert und abschließend im Vergleich mit der Terminologie entwicklungsbiologischer Experimente von H. Spemann aufgezeigt, die zunächst ganz ohne Gen- und Informationsbegriffe auskamen und erst sekundär mit diesen in einem Kausalitätssprachspiel zusammengeführt wurden.

Résumé

Dans le domaine de la génétique, la signification de la notion d’information (et des métaphores empruntées aux sciences de l’information) est souvent considérée comme dépendant du contexte, de même que la notion de gène elle-même. Parler « d’information génétique », comme cela est courant depuis les années 1960, est soumis dans le présent article à un nouvel examen essentiellement axé sur la critique linguistique. Il apparaît ici que la dominance de la métaphore de l’information dépend de sa diversité, qui permet une applicabilité à de nombreux niveaux, plus exactement dans différents jeux linguistiques. Ceci est montré dans le cas de jeux linguistiques dont le vocabulaire spécifique décrit l’expression génétique, p. ex. pour des jeux linguistiques relevant de la biochimie, de la cytologie, de la morphologie, ou encore pour des jeux linguistiques portant sur des textes et des informations (dans lesquels sont utilisées des notions telles que translation et transcription). Ces jeux linguistiques peuvent être qualifiés de sous-jeux linguistiques d’un métalangage génétique. Au lieu d’un discours sur les contextes, il convient donc d’effectuer une analyse des sous-jeux linguistiques concernés pour démontrer la portée de la métaphore de l’information directement par la structure des descriptions d’effets génétiques. On découvre ici que « l’information » a une fonction d’explanans, à savoir pour les protéines ou les phénotypes. On argumente que le déplacement de la métaphore de l’information en tant qu’explanans n’est possible qu’après une représentation exacte de l’explanandum. Ceci est tout d’abord illustré par une reconstruction méthodique des sciences génétiques, qui sont divisées à cet effet en trois phases : (1) génétique sans gènes, (2) génétique avec gènes, mais sans information, (3) génétique avec gènes et information. La modification de la notion de gène par sa jonction avec la métaphore de l’information est expliquée et démontrée pour terminer par une comparaison avec la terminologie des expériences d’évolution biologique de H. Spemann, qui au début se passèrent entièrement des notions de gène et d’information et qui ne furent rapprochées de ces dernières que dans un deuxième temps dans un jeu linguistique de causalité.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

With “metaphors”, we generally mean figurative expressions here. For a more detailed explanation of “metaphoric speech” see the article of Gutmann and Rathgeber in this volume.

Another reason is that Mendel’s introductory remarks can be interpreted in at least two ways. On the one hand he clearly defines his work as that of a hybridist (comp. Hartl and Orel 1992), on the other hand he states that his approach offers decisive clues for solving phylogenetical questions (comp. Gutmann 1998): “(...) der einzig, richtige Weg (...), auf dem endlich die Lösung einer Frage erreicht werden kann, welche für die Entwicklungs-Geschichte der organischen Formen von nicht zu unterschätzender Bedeutung ist.”(Mendel 1901: 4) “(…) this seems to be one correct way of finally reaching the solution to a question whose significance for the evolutionary history of organic forms must not be underestimated.”(translation by Corcos and Monaghan 1993: 59)

According to Mendel, elements are always different elements, i.e. two equal elements cannot be thought as two different entities, because they have the same character and therefore they cannot be distinguished (and lose their individual existence).

“This development proceeds in accord with a constant law based on the material composition and arrangement of the elements that attained a viable union in the cell.” (translation by Corcos and Monaghan 1993: 160)

Deduced from the Greek term “gignesthai”: to emerge, to be descended from.

Stating that for every genotype, there must be a phenotype. This genotype–phenotype-relation is non-transitive: For every given genotype, there is only one phenotype, but there is not always a single genotype for every given phenotype. In particular, the dominant phenotype indicates either a dominant homozygous or a heterozygous genotype while presence of the recessive phenotype always implies a homozygous recessive genotype. Therefore Mendel had to use test-crosses with homozygous recessive lines to unambiguously determine the genotype of the hybrid germ cells.

Janich (1999a, pp. 36) cites an etymological interpretation, according to which “information” as “content of a sentence” or “meaning” can be traced to Cicero, while “informare” as “forming something” is found in a text by Vergil (describing the production of a clipeum—a round, convex shield).

This should be seen independently from the question which research fields are in fact mostly stimulated by the results of the HGP. Critics as Sarkar (2006: 87) state that for some scientific disciplines, the hopes addressed to the HGP turned out to be futile: “Proponents of the HGP promised enormous immediate medical benefits. There have been none. (…) Instead, the emphasis now is on informatics: the design of computational tools to store and retrieve sequence information efficiently and reliably, with little expectation that any great theoretical insight is forthcoming.”

Under the condition of cultivations animals very often lose their ability to adequately raise their offspring.

in a very literal sense of the word.

References

Brandt C (2004) Metapher und Experiment. Von der Virusforschung zum genetischen Code. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen

Corcos AF, Monaghan FV (1993) Gregor Mendel’s experiments on plant hybrids. a guided study. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick

Crick FHC (1958) On protein synthesis. Symposium of the Society for Experimental Biology 12, New York, pp 138–163

Fischer EP (2003) Geschichte des Gens. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main

Gehring WJ (1998) Master control genes in development and evolution: the homeobox story. Yale University Press, New Haven

Godfrey-Smith P (2000) Information, arbitrariness, and selection: comments on Maynard Smith. Philos Sci 67:202–207 10.1086/392770

Goonatilake S (1991) The evolution of information. Lineages in gene, culture and artefact. Pinter, London

Griffiths PE (2001) Genetic Information: a metaphor in search of a theory. Philos Sci 68:394–412 10.1086/392891

Gutmann M (1998) Zur Ontologie des Genbegriffes: Systematische Rekonstruktionen zur Rationalen Genetik. In: Dally, A. (Hg.): Wie weit reicht die Macht der Gene? Loccumer Protokolle 22/98:27–58

Gutmann M (2005) Gene und Ethik. Wissenschaftstheoretische Rekonstruktionen zu einem Mißverständnis. In: Dabrock P, Ried J (Hg.) Therapeutisches Klonen als Herausforderung für die Statusbestimmung des menschlichen Embryos. Mentis, Paderborn, pp 89–108

Gutmann WF, Bonik K (1981) Kritische Evolutionstheorie. Gerstenberg, Hildesheim

Hadorn E (1981) Experimentelle Entwicklungsforschung. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Hartl DL, Orel V (1992) What did Gregor Mendel think he discovered? Genetics 131:245–253

Jablonka E (2002) Information: its interpretation, its inheritance, and its sharing. Philos Sci 69:578–605 10.1086/344621

Janich P (1999a) Die Naturalisierung der Information. Sitzungsberichte der wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft der Johann Wolfgang Goethe Universität Frankfurt a. M. Bd. XXXVII. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart

Janich P (1999b) Kritik des Informationsbegriffes in der Genetik. Theory Biosci 118:66–84

Kay L (2000) Who wrote the book of life? A history of the genetic code. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Loewenstein WR (1999) The touchstone of life. Molecular information, cell communication and the foundations of life. Oxford University press, New York

Maynard Smith J (2000) The concept of information in biology. Philos Sci 67:177–194 10.1086/392768

Mendel G (1901) Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden. Engelmann, Leipzig

Monaghan FV, Corcos AF (1990) The real objective of Mendel’s paper. Biol Philos 5:267–290 10.1007/BF00165254

Moss L (2003) What genes can’t do. Bradford Books Cambridge, London

Muller HJ (1922) Variation due to change in the individual gene. Am Nat 56:32–50 10.1086/279846

Neumann-Held E, Rehmann-Sutter C (1999) Individuation and reality of genes. A comment to Peter Beurtons article: “Was sind Gene heute?” Theory Biosci 118:85–95

Olby R (1979) Mendel no Mendelian? Hist Sci 17:53–72

Pearson H (2006) What is a gene? Nature 441:398–401 10.1038/441398a

Raible F, Arendt D (2004) Metazoan evolution—some animals are more equal than others. Curr Biol 14:R106–R108

Rheinberger HJ (1997) Toward a history of epistemic things. Synthesizing proteins in the test tube. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Rheinberger HJ (2006a) Die Evolution des Genbegriffes – Perspektiven der Molekularbiologie. S.221–244, in: Epistemologie des Konkreten. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt: 415 S

Rheinberger HJ (2006b) Regulation, Information, Sprache – Molekulargenetische Konzepte in Francois Jacobs Schriften. S. 293–309, in: Epistemologie des Konkreten. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt:415 S

Riley M, Pardee BA, Jacob F, Monod J (1960) On the expression of a structural gene. J Mol Biol 2:216–225 10.1016/S0022-2836(60)80039-3

Rinaudo K, Bleris L, Maddamsetti R, Subramanian S, Weiss R, Beneson Y (2007) A universal RNAi-based logic evaluator that operates in mammalian cells. Nat Biotechnol 25:795–801 10.1038/nbt1307

Roof J (2007) The poetics of DNA. University of Minnesota Publications

Sarkar S (2000) Information in genetics and developmental biology: comments on Maynard Smith. Philos Sci 67:208–213 10.1086/392771

Sarkar S (2006) From genes as determinants to DNA as resource. Historical notes on development and genetics. In: Neumann-Held E, Rehmann-Sutter C (eds) Genes in development. Re-reading the molecular paradigm. Duke University Press, Durham, pp 77–95

Searls DB (2002) The language of genes. Nature 420:211–217 10.1038/nature01255

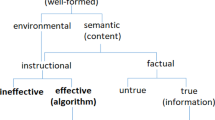

Stegmann UE (2005) Genetic information as instructional content. Philos Sci 72:425–443 10.1086/498472

Sterelny K (2000) The “genetic program” program: a commentary on Maynard Smith on information in biology. Philos Sci 67:195–201 10.1086/392769

Telford MJ, Copley RR (2005) Animal phylogeny: fatal attraction. Curr Biol 15:R296–R299 10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.001

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the BMBF research initiative “Geisteswissenschaften im gesellschaftlichen Dialog”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Syed, T., Bölker, M. & Gutmann, M. Genetic “information” or the indomitability of a persisting scientific metaphor. Poiesis Prax 5, 193–209 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10202-008-0048-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10202-008-0048-0