Abstract

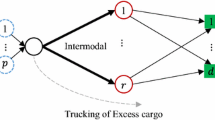

Empty containers need to be repositioned from a surplus area to a shortage area, and the resulting economies of scope mean that the canvassing (i.e., the sale of transportation service) of two routes back and forth is no longer isolated. To study the liner company’s canvassing strategy for round-trip routes, this paper considers a benchmark situation where one forwarder is responsible for two directions and three canvassing sequences with one direction one freight forwarder responsibility. The results indicate that the liner company should focus canvassing on fewer forwarders, and the forwarder should expand service scope. Under one direction one freight forwarder responsibility, it is not necessarily optimal for the liner company that the direction with low potential market demand canvasses first. Examining the preferences of the liner company and two forwarders in terms of canvassing strategy, we find that a triple-win situation can not be formed, but only a win-win situation can be formed between the two of the three participants. Although the canvassing strategy where the direction with high potential market demand canvasses first has the worst effect on balancing cargo flow, it is possible to increase the market share while improving the profit of the liner company.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

References

Akan, M., Ata, B., & Lariviere, M. A. (2011). Asymmetric information and economies of scale in service contracting. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 13(1), 58–72.

Altuntas, M., Berry-Stölzle, T. R., & Cummins, J. D. (2019). Enterprise risk management and economies of scale and scope: Evidence from the German insurance industry. Annals of Operations Research,. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-019-03393-x.

Basu, R. J., Bai, R., & Palaniappan, P. L. K. (2015). A strategic approach to improve sustainability in transportation service procurement. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 74, 152–168.

Cachon, G. P., & Harker, P. T. (2002). Competition and outsourcing with scale economies. Management Science, 48(10), 1314–1333.

Carlsson, J. G., Behroozi, M., Devulapalli, R., & Meng, X. (2016). Household-level economies of scale in transportation. Operations Research, 64(6), 1372–1387.

Chao, S. L., & Chen, C. C. (2015). Applying a time-space network to reposition reefer containers among major Asian ports. Research in Transportation Business & Management, 17, 65–72.

Cheaitou, A., & Cariou, P. (2019). Greening of maritime transportation: A multi-objective optimization approach. Annals of Operations Research, 273(1–2), 501–525.

Chen, R., Dong, J. X., & Lee, C. Y. (2016). Pricing and competition in a shipping market with waste shipments and empty container repositioning. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 85, 32–55.

Cheraghchi, F., Abualhaol, I., Falcon, R., Abielmona, R., Raahemi, B., & Petriu, E. (2018). Modeling the speed-based vessel schedule recovery problem using evolutionary multiobjective optimization. Information Sciences, 448, 53–74.

Cheung, R. K., & Chen, C. Y. (1998). A two-stage stochastic network model and solution methods for the dynamic empty container allocation problem. Transportation Science, 32(2), 142–162.

Chu, X., Zhong, Q., & Li, X. (2018). Reverse channel selection decisions with a joint third-party recycler. International Journal of Production Research, 56(18), 5969–5981.

Dulebenets, M. A. (2018). Minimizing the total liner shipping route service costs via application of an efficient collaborative agreement. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 20(1), 123–136.

Erera, A. L., Morales, J. C., & Savelsbergh, M. (2009). Robust optimization for empty repositioning problems. Operations Research, 57(2), 468–483.

Ge, H., Goetz, S., Canning, P., & Perez, A. (2018). Optimal locations of fresh produce aggregation facilities in the United States with scale economies. International Journal of Production Economics, 197, 143–157.

Gürel, S., & Shadmand, A. (2019). A heterogeneous fleet liner ship scheduling problem with port time uncertainty. Central European Journal of Operations Research, 27(4), 1153–1175.

Joborn, M., Crainic, T. G., Gendreau, M., Holmberg, K., & Lundgren, J. T. (2004). Economies of scale in empty freight car distribution in scheduled railways. Transportation Science, 38(2), 121–134.

Lee, C. Y., & Song, D. P. (2017). Ocean container transport in global supply chains: Overview and research opportunities. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 95, 442–474.

Lee, C. Y., Tang, C. S., Yin, R., & An, J. (2015). Fractional price matching policies arising from the ocean freight service industry. Production and Operations Management, 24(7), 1118–1134.

Lim, A., Rodrigues, B., & Xu, Z. (2008). Transportation procurement with seasonally varying shipper demand and volume guarantees. Operations Research, 56(3), 758–771.

Li, S., & Marinč, M. (2018). Economies of scale and scope in financial market infrastructures. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 53, 17–49.

Ma, D., & Seidmann, A. (2015). Analyzing software as a service with per-transaction charges. Information Systems Research, 26(2), 360–378.

Keh, H. T., & Chu, S. (2003). Retail productivity and scale economies at the firm level: A DEA approach. Omega, 31(2), 75–82.

Kong, X. T. R., Chen, J., Luo, H., & Huang, G. Q. (2016). Scheduling at an auction logistics centre with physical internet. International Journal of Production Research, 54(9), 2670–2690.

Kuzmicz, K. A., & Pesch, E. (2019). Approaches to empty container repositioning problems in the context of Eurasian intermodal transportation. Omega, 85, 194–213.

Pasha, J., Dulebenets, M. A., Kavoosi, M., et al. (2020). Holistic tactical-level planning in liner shipping: An exact optimization approach. Journal of Shipping and Trade, 5, 1–35.

Poo, M. C. P., & Yip, T. L. (2019). An optimization model for container inventory management. Annals of Operations Research, 273(1–2), 433–453.

Remli, N., & Rekik, M. (2013). A robust winner determination problem for combinatorial transportation auctions under uncertain shipment volumes. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 35, 204–217.

Rodrigue, J. P., Comtois, C., & Slack, B. (2013). The Geography of Transport Systems. New York: Routledge.

Sheffi, Y. (2004). Combinatorial auctions in the procurement of transportation services. Interfaces, 34(4), 245–252.

Song, D. P., & Dong, J. X. (2012). Cargo routing and empty container repositioning in multiple shipping service routes. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 46(10), 1556–1575.

Song, Z., Tang, W., & Zhao, R. (2017). Ocean carrier canvassing strategies with uncertain demand and limited capacity. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 104, 189–210.

Song, Z., Tang, W., & Zhao, R. (2019). Encroachment and canvassing strategy in a sea-cargo service chain with empty container repositioning. European Journal of Operational Research, 276(1), 175–186.

UNCTAD. (2019). Review of maritime transport, 2019. United Nations Publications. Retrieved January 18, 2020. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/rmt2019_en.pdf.

Wang, F., Zhuo, X., Niu, B., & He, J. (2017). Who canvasses for cargos? Incentive analysis and channel structure in a shipping supply chain. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 97, 78–101.

Wang, S., Liu, Z., & Bell, M. G. H. (2015). Profit-based maritime container assignment models for liner shipping networks. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 72, 59–76.

Wang, Y., Meng, Q., & Kuang, H. (2019). Intercontinental liner shipping service design. Transportation Science, 53(2), 344–364.

Wanke, P. F. (2012). Determinants of scale efficiency in the Brazilian 3PL industry: A 10-year analysis. International Journal of Production Research, 50(9), 2423–2438.

Xu, L., Govindan, K., Bu, X., & Yin, Y. (2015). Pricing and balancing of the sea-cargo service chain with empty equipment repositioning. Computers & Operations Research, 54, 286–294.

Xu, S. X., Huang, G. Q., & Cheng, M. (2016). Truthful, budget-balanced bundle double auctions for carrier collaboration. Transportation Science, 51(4), 1365–1386.

Yang, R., Lee, C. Y., Liu, Q., & Zheng, S. (2019). A carrier–shipper contract under asymmetric information in the ocean transport industry. Annals of Operations Research, 273(1–2), 377–408.

Yun, W. Y., Lee, Y. M., & Choi, Y. S. (2011). Optimal inventory control of empty containers in inland transportation system. International Journal of Production Economics, 133(1), 451–457.

Zheng, J., Sun, Z., & Gao, Z. (2015). Empty container exchange among liner carriers. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 83, 158–169.

Zhou, W. H., & Lee, C. Y. (2009). Pricing and competition in a transportation market with empty equipment repositioning. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 43(6), 677–691.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 71771164.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Proof of Lemma 1

According to the profit function, to solve the forwarder’s optimization problem, we first define the following two problems:

And then proving the above two problems is equivalent to the original problem which is denoted by \(P_{\mathrm{OS}}^{}\). Let \(q_\mathrm{i}^{\mathrm{OS}}\), \({\bar{q}}_{i}^{}\), \({\underline{q}}_{i}^{}\), \(i\in \{A,\,B\}\) denote the optimal solutions to the original problem \(P_{\mathrm{OS}}^{}\) and two new problems \({\bar{P}}_{\mathrm{OS}}^{}\) and \({\underline{P}}_{\mathrm{OS}}^{}\), respectively. The forwarder’s corresponding optimal profits of these three problems are \(\pi _\mathrm{OS}^*\), \({\bar{\pi }}_{\mathrm{OS}}^*\), \({\underline{\pi }}_{\mathrm{OS}}^*\). Then we must have \(\pi _{\mathrm{OS}}^*=\max ({\bar{\pi }}_\mathrm{OS}^*,\,{\underline{\pi }}_{\mathrm{OS}}^*)\). The proof as follows: Since \({\bar{q}}_{i}^{}\) is feasible to \(P_{\mathrm{OS}}^{}\), we have \(\pi _\mathrm{OS}^*\geqslant {\bar{q}}_{A}^{}(a-{\bar{q}}_{A}^{})+{\bar{q}}_{B}^{}(\delta a-{\bar{q}}_{B}^{})-2\min ({\bar{q}}_{A}^{},\,{\bar{q}}_{B}^{})(w-\tau \min ({\bar{q}}_{A}^{},\,{\bar{q}}_{B}^{}))-(w+\tau (({\bar{q}}_{B}^{}-{\bar{q}}_{A}^{})^++({\bar{q}}_{A}^{}-{\bar{q}}_{B}^{})^+))(({\bar{q}}_{B}^{}-{\bar{q}}_{A}^{})^++({\bar{q}}_{A}^{}-{\bar{q}}_{B}^{})^+)={\bar{q}}_{A}^{}(a-{\bar{q}}_{A}^{})+{\bar{q}}_{B}^{}(\delta a-{\bar{q}}_{B}^{})-2{\bar{q}}_{B}^{}(w-\tau {\bar{q}}_{B}^{})-(w+\tau ({\bar{q}}_{A}^{}-{\bar{q}}_{B}^{}))({\bar{q}}_{A}^{}-{\bar{q}}_{B}^{})={\bar{\pi }}_\mathrm{OS}^*\). Similarly, we have \(\pi _\mathrm{OS}^*\geqslant {\underline{\pi }}_{\mathrm{OS}}^*\), then \(\pi _\mathrm{OS}^*\geqslant \max ({\bar{\pi }}_{\mathrm{OS}}^*,\,{\underline{\pi }}_\mathrm{OS}^*)\). Besides, if \(q_{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{OS}}-q_{\mathrm{B}}^\mathrm{OS}\leqslant 0\), then \(q_{\mathrm{i}}^{\mathrm{OS}}\) is feasible to \({\underline{P}}_{\mathrm{OS}}^{}\), so we have \({\underline{\pi }}_\mathrm{OS}^*\geqslant q_{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{OS}}(a-q_{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{OS}})+q_\mathrm{B}^{\mathrm{OS}}(\delta a-q_{\mathrm{B}}^{\mathrm{OS}})-2q_{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{OS}}(w-\tau q_{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{OS}})-(w+\tau (q_{\mathrm{B}}^{\mathrm{OS}}-q_{\mathrm{A}}^\mathrm{OS}))(q_{\mathrm{B}}^{\mathrm{OS}}-q_{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{OS}})=\pi _{\mathrm{OS}}^*\). Therefore, \(\pi _{\mathrm{OS}}^*\leqslant \max ({\bar{\pi }}_\mathrm{OS}^*,\,{\underline{\pi }}_{\mathrm{OS}}^*)\).

Thus, we first solve the above two new problems. To solve the problem \({\bar{P}}_{\mathrm{OS}}^{}\), the Hessian matrix of \({\bar{\pi }}_\mathrm{OS}^{}\) is:

It is easy to see that the Hessian matrix is negative definite. Hence, \({\bar{\pi }}_{\mathrm{OS}}^{}\) is concave function. Obviously, the feasible region is a convex set. Therefore, \({\bar{P}}_{\mathrm{OS}}^{}\) is a convex programming problem. Therefore, we can use Karush–Kuhn–Tucker conditions to solve this optimization problem. The Lagrangian is \(L=q_{A}^{}(a-q_{A}^{})+q_{B}^{}(\delta a-q_{B}^{})-2q_{B}^{}(w-\tau q_{B}^{})-(w+\tau (q_{A}^{}-q_{B}^{}))(q_{A}^{}-q_{B}^{})+\mu _{1}(q_{A}^{}-q_{B}^{})\). Taking the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker conditions, we have

Then, we can get the optimal pricing for \({\bar{P}}_{\mathrm{OS}}^{}\) under different cases as follows:

-

1.

when \(w\leqslant \frac{(2\tau +\delta -1)a}{2\tau }\), \({\bar{q}}_{A}^{}={\bar{q}}_{B}^{}=\frac{a\delta +a-2w}{4(1-\tau )}\),

-

2.

when \(w>\frac{(2\tau +\delta -1)a}{2\tau }\), \({\bar{q}}_{A}^{}=\frac{a\delta \tau -a\tau +a-w}{2(1-2\tau ^2)},\,{\bar{q}}_{B}^{}=\frac{a\delta \tau +a\delta +a\tau -2\tau w-w}{2(1-2\tau ^2)}\).

\({\underline{P}}_{\mathrm{OS}}^{}\) is quite similar to \({\bar{P}}_\mathrm{OS}^{}\) and the optimal solutions can be obtained in the same way. Then we only need to compare the profits in these two problems and find the optimal solution to the original problem \(P_{\mathrm{OS}}^{}\). The comparison process is straightforward and thus is omitted.

Then we can calculate the forwarder’s corresponding ordered quantity which are summarized in Lemma 1. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 1

Substitute the forwarder’s ordered quantity of Lemma 1 into the liner company’s profit and the corresponding quantity conditions are converted to the base wholesale price. That is, the liner company’s optimization problem is transformed into the following two sub-problems:

After the solution process similar to Lemma 1, the liner company’s optimal base wholesale price can be obtained and the forwarder’s optimal ordered quantities can get by back substitution which are summarized in Proposition 1.

Proof of Lemma 2

Based on Eqs. (4) and (5), the profit functions of the two forwarders are discontinuous as follows:

Following from the first-order condition, we obtain the maximum of \(\pi _{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{TS}}\) and \(\pi _{\mathrm{B}}^{\mathrm{TS}}\) with which the reaction functions are composed.

We formulate the reaction functions as:

The intersection of \(q_{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{re}}\) and \(q_{\mathrm{B}}^{\mathrm{re}}\) is the equilibrium point \(q_\mathrm{A}^*=\frac{(1+\delta \tau -\tau )a-w}{2(1-\tau ^2)}\) and \(q_\mathrm{B}^*=\frac{\delta a-w}{2(1-\tau )}\) with the condition \(w\geqslant \frac{(\delta +\tau -1)a}{\tau }\). \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 2

Substitute the forwarder’s ordered quantity of Lemma 2 into the liner company’s profit and the liner company’s optimization problem is transformed as follows:

The following solution process is similar to Lemma 1 and use the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker conditions. Then, the liner company’s optimal base wholesale price can be obtained and the forwarders’ optimal ordered quantities can get by back substitution which are summarized in Proposition 2. \(\square \)

Proof of Corollary 1

Under the case OS, the order quantity is the same in each direction when \(\delta >\delta _{1}\) and the condition under the case TS is \(\delta >\delta _{3}\). It is easy to prove \(\delta _{1}<\delta _{3}\). \(\square \)

Proof of Lemma 3

Although there is a Stackelberg game between the two forwarders, the forwarder A’s decision completely don’t need to consider the forwarders B’s decision because there’s no \(q_{B}^{}\) in Eq. (7). Hence, we can solve the decision of forwarder A according to the actual game sequence. Since \(\frac{\mathrm{d}^2\pi _{\mathrm{A}}^\mathrm{TA}}{\mathrm{d q}_{A}^2}=-2(1-\tau )<0\), according to the first-order condition, we can obtain \(q_{A}^*\) by solving the equation \(\frac{\mathrm{d}\pi _{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{TA}}}{\mathrm{d q}_{A}^{}}=2\tau q_{A}^{}+a-w-2q_{A}^{}=0\). Substitute \(q_{A}^*\) into the forwarder B’s profit and the solution process of forwarder B’s optimization problem is similar to Lemma 1 and use the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker conditions. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 3

In this case, the two forwarders’ quantity decisions is not affected by other parameters and thus the optimization problem of the liner company is unconstrained. Since \(\frac{\mathrm{d}^2\varPi _{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{TA}}}{\mathrm{d w}^2}=\frac{-(2-\tau )}{(1-\tau )^2}<0\), according to the first-order condition, we can obtain \(w^{\mathrm{TA}}\) by solving the equation \(\frac{\mathrm{d}\varPi _{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{TA}}}{\mathrm{d w}}=\frac{(2w-2c)\tau +(1+\delta )a+2c-4w)}{2(1-\tau )^2}=0\) and the forwarders’ optimal ordered quantities can get by back substitution. \(\square \)

Proof of Lemma 4

The solution process of forwarders’ optimization problem is similar to Lemma 3. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 4

The solution process of the liner company’s optimization problem is similar to proposition 1 and then the forwarders’ optimal ordered quantities can get by back substitution. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 5

The liner company’s profit under each strategy are as follows:

To examine the liner company’s preference for canvassing strategy, we need to determine the size relationship of the threshold value under each strategy. When \(e>\frac{a-c}{2}\), there is \(\delta _{1}<\delta _{2}<\delta _{3}=\delta _{4}<\delta _{5}\); when \(e\leqslant \frac{a-c}{2}\), there is \(\delta _{1}<\delta _{2}<\delta _{4}=\delta _{5}<\delta _{3}\).

For part 1), if \(\delta \in (\delta _{2},\,\delta _{3}]\) with \(e>\frac{a-c}{2}\), \(\varPi _{\mathrm{OS}}^*-\varPi _{\mathrm{TS}}^*=\frac{1}{8(\tau -2)(\tau ^3-4\tau -4)}((3\tau ^2-10)a^2\tau \delta ^2+(4a\tau ^2(c-a+3e)-2a\tau ^3(a+2c)+4\tau (5a^2-2ae)-32ae)\delta +(4a(2c+e)-3a^2-2c^2-4ce+2e^2)\tau ^3+4\tau ^2(2a^2-3a(e+c)+c^2-e^2)+2\tau (4c(c+2e)-a^2-4a(2c+e))+32ae)\), which can be easily proved to be greater than 0 in this interval. Other cases are available accordingly.

For part 2), through the comparison of \(\varPi _{\mathrm{TS}}^*\), \(\varPi _{\mathrm{TA}}^*\) and \(\varPi _{\mathrm{TB}}^*\) can be obtained. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 6

The order quantities for each strategy in both directions are as follows:

and

Then, this proposition can be easily obtained by making a difference. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 7

The total order quantity for both directions is \(q_{\mathrm{A}}^{}+q_{\mathrm{B}}^{}\). This proposition can be obtained by a simple differential comparison. Thereinto, when \(\delta \in (0,\,\delta _{1}]\), it is easy to prove that \((q_{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{OS}}+q_{\mathrm{B}}^{\mathrm{OS}})>(q_{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{TS}}+q_{\mathrm{B}}^{\mathrm{TS}})=(q_{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{TB}}+q_{\mathrm{B}}^\mathrm{TB})\). And \((q_{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{OS}}+q_{\mathrm{B}}^{\mathrm{OS}})-(q_{\mathrm{A}}^{\mathrm{TA}}+q_{\mathrm{B}}^{\mathrm{TA}})=\frac{a\tau ^2\delta +(a-c-e)\tau ^3-(a-e)\tau ^2+2e\tau }{(\tau -2)(2\tau ^3-3\tau -2)}\), which is less than 0 when \(\delta \leqslant \delta _{7}\) and \(\delta _{7}<\delta _{1}\). \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 8

Under the case OS, empty containers repositioning occurs when \(\delta \leqslant \delta _{1}\) and the empty container quantity which needs to be repositioned from port B to port A is \(Q_{\mathrm{B A}}^{\mathrm{O S}}=\frac{(a-c+e)\tau ^2+(a\delta -c)\tau -a(1-\delta )}{2\tau ^3-3\tau -2}\); Under the case TS, empty containers repositioning occurs when \(\delta \leqslant \delta _{3}\) and the empty container quantity which needs to be repositioned from port B to port A is \(Q_{\mathrm{B\!A}}^{\mathrm{T\!S}}=\frac{(a-c+e)\tau ^2+((3\delta -1)a-2c)\tau -4a(1-\delta )}{2(\tau ^3-4\tau -4)}\); Under the case TA, empty containers repositioning always occurs and the empty container quantity which needs to be repositioned from port B to port A is \(Q_{\mathrm{B\!A}}^{\mathrm{T\!A}}=\frac{a(1-\delta )}{2(1-\tau )}\); Under the case TB, empty containers repositioning occurs when \(\delta \leqslant \delta _{4}\) and the empty container quantity which needs to be repositioned from port B to port A is \(Q_{\mathrm{B\!A}}^{\mathrm{T\!B}}=\frac{(a-c+e)\tau ^2+((3\delta -1)a-2c)\tau -4a(1-\delta )}{2(\tau ^3-4\tau -4)}\). This proposition can be obtained by a simple differential comparison. \(\square \)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Song, Z., Tang, W. & Zhao, R. Implications of economies of scale and scope for round-trip shipping canvassing with empty container repositioning. Ann Oper Res 309, 485–515 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-020-03735-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-020-03735-0