Abstract

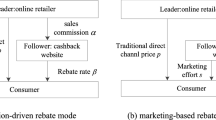

This paper considers a capital-constrained online retailer (OR) selling products through an e-commerce platform (EP) who also offers financial services to retailers. During the selling season, the OR exerts an effort to promote market demand through activities like sales promotions, advertising and live-streaming selling events. To investigate the EP-based financing scheme, a game-theoretic model is developed where the EP functions as the leader determining the interest rate and platform usage fee rate, and the OR functions as the follower determining the order quantity and effort level. We explore the impacts of the OR’s risk-aversion and find that when the OR is risk-averse (1) she sets a high effort level, and the EP sets a high usage fee rate; (2) a high risk-averse OR orders less products than low risk-averse OR. We design specific revenue-cost sharing contracts to coordinate the supply chain and demonstrate that the designed contracts are feasible. Moreover, we find that the OR consistently prefers EP financing compared to bank financing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

“Amazon 2020 SMB Impact Report Highlights Success for Small and Medium-Sized Businesses Despite COVID-19; American Sellers Average $160,000 in Annual Sales”, accessed on July 30, 2021, https://press.aboutamazon.com/news-releases/news-release-details/amazon-2020-smb-impact-report-highlights-success-small-and.

“MYbank’s use of digital technology leads to record growth in rural clients”, accessed on July 30, 2021, https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210623005998/en/MYbank%E2%80%99s-Use-of-Digital-Technology-Leads-to-Record-Growth-in-Rural-Clients.

“ City alliance investing in potential of companies”, accessed on July 30, 2021, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/cndy/2019-08/15/content_37502052.htm

“Addressing the SME finance problem”, accessed on August 2, 2021, http://blogs.worldbank.org/allaboutfinance/addressing-sme-finance-problem.

“China's Singles Day shopping spree injects impetus into global economy”, accessed on June, 13, 2021, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202011/12/WS5fad0059a31024ad0ba93bb8.html.

“How to Deal with Uncertainty in the Supply Chain”, access on August 2, 2021, https://news.thomasnet.com/imt/2011/01/11/how-to-deal-with-uncertainty-in-the-supply-chain.

In practice, EPs can serve as resellers (e.g., Tmall) and agency sellers (e.g., Amazon, JD.com). In this paper, we consider the situation that the EP acts as agency seller. Please refer to Abhishek et al. (2016) for further discussions on the differences between agency selling and reselling.

For example, JD.com is one of the China’s largest EP and operates a network of over 650 warehouses. This EP provides warehousing and e-tailing services for the ORs. See https://corporate.jd.com/ourBusiness.

References

Abhishek, V., Jerath, K., & Zhang, Z. J. (2016). Agency selling or reselling? Channel structures in electronic retailing. Management Science, 62(8), 2259–2280.

Abor, J. Y., Agbloyor, E. K., & Kuipo, R. (2014). Bank finance and export activities of small and medium enterprises. Review of Development Finance, 4(2), 97–103.

Alan, Y., & Gaur, V. (2018). Operational investment and capital structure under asset-based lending. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 20(4), 637–654.

Ali, M. S., & Nakade, K. (2016). Coordinating a supply chain system for production, pricing and service strategies with disruptions. International Journal of Advanced Operations Management, 8(1), 17–37.

Buzacott, J. A., & Zhang, R. Q. (2004). Inventory Management with asset-based financing. Management Science, 50(9), 1274–1292.

Cachon, G. P. (2003). Supply chain coordination with contracts. Handbooks in Operation Research and Management Science, 11, 227–339.

Cachon, G. P., & Lariviere, M. A. (2005). Supply chain coordination with revenue-sharing contracts: Strengths and limitations. Management Science, 50(1), 30–44.

Cai, G., Dai, Y., & Zhou, S. (2012). Exclusive channels and revenue sharing in a complementary goods market. Marketing Science, 31(1), 172–187.

Cao, E., & Yu, M. (2018). Trade credit financing and coordination for an emission-dependent supply chain. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 119, 50–62.

Chen, C., Zhuo, X., & Li, Y. (2021). Online channel introduction under contract negotiation: Reselling versus agency selling. In Press.

Chen, X. (2015). A model of trade credit in a capital-constrained distribution channel. International Journal of Production Economics, 159(1), 347–357.

Chen, X., Liu, C., & Li, S. (2019). The role of supply chain finance in improving the competitive advantage of online retailing enterprises. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 33, 100821.

Chiu, C. H., & Choi, T. M. (2016). Supply chain risk analysis with mean-variance models: A technical review. Annals of Operations Research, 240(2), 489–507.

Chod, J., Lyandres, E., & Yang, S. A. (2019). Trade credit and supplier competition. Journal of Financial Economics, 131(2), 484–505.

Choi, T. M. (2020b). Supply chain financing using blockchain: Impacts on supply chains selling fashionable products. Annals of Operations Research, 1–23.

Choi, T. M., & Chiu, C. H. (2012). Risk analysis in stochastic supply chains: A mean-risk approach. Springer.

Choi, T. M., Chung, S. H., & Zhuo, X. (2020). Pricing with risk sensitive competing container shipping lines: Will risk seeking do more good than harm? Transportation Research Part B-Methodological, 133, 210–229.

Cui, Q., Chiu, C. H., Dai, X., & Li, Z. (2016). Store brand introduction in a two-echelon logistics system with a risk-averse retailer. Transportation Research Part E-Logistics and Transportation Review, 90, 69–89.

Gang, X., Wang, S., & Lai, K. K. (2011). Quality investment and price decision in a risk-averse supply chain. European Journal of Operational Research, 214(2), 403–410.

Gong, D., Liu, S., Liu, J., Ren, L. 2019. Who benefits from online financing? A sharing economy E-tailing platform perspective. International Journal of Production Economics. In Press

He, J., Ma, C., & Pan, K. (2017). Capacity investment in supply chain with risk averse supplier under risk diversification contract. Transportation Research Part E, 106, 255–275.

Heydari, J., Govindan, K., & Basiri, Z. (2020). Balancing price and green quality in presence of consumer environmental awareness: A green supply chain coordination approach. International Journal of Production Research, 59(7), 1–19.

Hosseini-Motlagh, S., Jazinaninejad, M., Nami, N. (2020). Recall management in pharmaceutical industry through supply chain coordination. Annals of Operations Research, 1–39.

Huo, Y., Lee, C. K. M., Zhang, S. (2020). Trinomial tree based option pricing model in supply chain financing. Annals of Operations Research, 1–21.

Jammernegg, W., Kischka, P. 2012. Newsvendor problems with VaR and CVaR consideration. In T.M. Choi (Ed.), Handbook on newsvendor problems: Models, Extensions and Applications.

Katehakis, M. N., Melamed, B., & Shi, J. (2016). Cash-flow based dynamic inventory management. Production and Operations Management, 25(9), 1558–1575.

Kouvelis, P., & Zhao, W. (2011). The newsvendor problem and price-only contract when bankruptcy costs exist. Production and Operations Management, 20(6), 921–936.

Lariviere, M. A., & Porteus, E. L. (2001). Selling to the newsvendor: An analysis of price-only contracts. Manufacturing and Service Operations Management, 3(4), 293–305.

Lau, H. S., Su, C., Wang, Y. Y., & Hua, Z. S. (2012). Volume discounting coordinates a supply chain effectively when demand is sensitive to both price and sales effort. Computers & Operations Research, 39(12), 3267–3280.

Lee, C. H., & Rhee, B. D. (2011). Trade credit for supply chain coordination. European Journal of Operational Research, 214(1), 136–146.

Li, B., An, S., & Song, D. P. (2018). Selection of financing strategies with a risk-averse supplier in a capital-constrained supply chain. Transportation Research Part E-Logistics and Transportation Review, 118, 163–183.

Li, X., Du, J., & Long, H. (2020). Mechanism for green development behavior and performance of industrial enterprises (GDBP-IE) using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8450.

Lin, Q., Su, X., & Peng, Y. (2018). Supply chain coordination in confirming warehouse financing. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 118, 104–111.

Liu, M., Cao, E., & Salifou, C. K. (2016). Pricing strategies of a dual-channel supply chain with risk aversion. Transportation Research Part E, 90, 108–120.

Long, H., Liu, H., Li, X., & Chen, L. (2020). An evolutionary game theory study for construction and demolition waste recycling considering green development performance under the Chinese Government’s reward-penalty mechanism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6303.

Luciano, E., Peccati, L., & Cifarelli, D. M. (2003). VaR as a risk measure for multiperiod static inventory models. International Journal of Production Economics, 81–82, 375–384.

Mamun, A. A., Khaled, A. A., Ali, S. M., & Chowdhury, M. M. (2012). A heuristic approach for balancing mixed-model assembly line of type I using genetic algorithm. International Journal of Production Research, 50(18), 5106–5116.

Moon, I., Dey, K., & Saha, S. (2018). Strategic inventory: Manufacturer vs. retailer investment. Transportation Research Part E-Logistics and Transportation Review, 109, 63–82.

Rockafellar, R. T., & Uryasev, S. (2002). Conditional value-at-risk for general loss distributions. Journal of Banking & Finance, 26, 144–1471.

Shi, J., Du, Q., Lin, F., Li, Y., Bai, L., Fung, R. Y. K., & Lai, K. K. (2020). Coordinating the supply chain finance system with buyback contract: A capital-constrained newsvendor problem. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 146, 106587.

Tang, C. S., Yang, S. A., & Wu, J. (2017). Sourcing from suppliers with financial constraints and performance risk. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 20(1), 70–84.

Tapiero, C. S. (2005). Value at risk and inventory control. European Journal of Operational Research, 163(3), 769–775.

Wang, C., Fan, X., & Yin, Z. (2019a). Financing online retailers: Bank vs. electronic business platform, equilibrium, and coordinating strategy. European Journal of Operational Research, 276, 343–356.

Wang, F., Yang, X., Zhuo, X., & Xiong, M. (2019b). Joint logistics and financial services by a 3PL firm: Effects of risk preference and demand volatility. Transportation Research Part E-Logistics and Transportation Review, 130, 312–328.

World Bank Group. 2018. Finance. access on June 25, 2019. https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/data.

Wu, J., Yue, W., Yamamoto, Y., & Wang, S. (2006). Risk analysis of a pay to delay capacity reservation contract. Optimization Methods & Software, 21, 635–651.

Xu, Y., Pinedo, M., & Xue, M. (2016). Operational risk in financial services: A review and new research opportunities. Production and Operations Management, 26(3), 426–445.

Yan, N., He, X., Liu, Y. 2018. Financing the capital-constrained supply chain with loss aversion: supplier finance vs. supplier investment. Omega. In press.

Yan, N., Liu, Y., Xu, X., & He, X. (2020). Strategic dual-channel pricing games with e-retailer finance. European Journal of Operational Research, 283, 138–151.

Yan, N., & Sun, B. (2013). Coordinating loan strategies for supply chain financing with limited credit. Or Spectrum, 35(4), 1039–1058.

Yan, N., Sun, B., Zhang, H., & Liu, C. (2016). A partial credit guarantee contract in a capital-constrained supply chain: Financing equilibrium and coordinating strategy. International Journal of Production Economics, 173, 122–133.

Yang, S. A., Birge, J. (2017a). Trade credit, risk sharing, and inventory financing portfolios. Management Science. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2746645.

Yang, S. A., Birge, J. (2017b). Trade credit in supply chains: multiple creditors and priority rules. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1840663.

Zhang, J., Sethi, S. P., Choi, T. M., & Cheng, T. C. E. (2020). Supply chains involving a mean-variance-skewness-kurtosis newsvendor: Analysis and coordination. Production and Operations Management, 29(6), 1397–1430.

Zhang, Q., Dong, M., Luo, J., & Segerstedt, A. (2014). Supply chain coordination with trade credit and quantity discount incorporating default risk. International Journal of Production Economics, 153, 352–360.

Zheng, K., Zhang, Z., Gauthier, J. (2020). Blockchain-based intelligent contract for factoring business in supply chains. Annals of Operations Research, 1–21.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the editors and the reviewers for their helpful comments. This work is partially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Nos. 72071050, 71901227 and U1811462) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province of China (No. 2022A1515010541).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Proof of Lemma 1

In the centralized case, we have \(\left(1-\lambda \right)p>w +{c}_{2}>s\). From the second-order derivative of \(E\left[{\pi }_{SC}\right]\) with respect to \(Q\) and \(e\), we have \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}E\left[{\pi }_{SC}\right]}{\partial {Q}^{2}}=\left(s-\left(1-\lambda \right)p\right)f\left(Q-e\right)<0\) and \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}E\left[{\pi }_{SC}\right]}{\partial {e}^{2}}=-\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)f\left(Q-e\right)-2a<0\). Hence, by solving \(\frac{\partial E[{\pi }_{SC}]}{\partial Q}=0\) and \(\frac{\partial E[{\pi }_{SC}]}{\partial e}=0\), we derive \({e}^{C}=\frac{p-w-{c}_{2}}{2a}\) and \({Q}^{C}={F}^{-1}\left[\frac{p-w-{c}_{2}}{p-s}\right]+\frac{p-w-{c}_{2}}{2a}\). Q.E.D.

Proof of Proposition 1

Similar to the Proof of Lemma 1, we can easily obtain the results of \({e}^{BN}\) and \({Q}^{BN}\). From the first-order derivative of \(E\left[{\pi }_{p}\right]\) on \(\lambda \), we have \(\frac{dE[{\pi }_{p}]}{d\lambda }=ph\left({Q}^{BN},{e}^{BN}\right)+\lambda p\frac{dh\left({Q}^{BN},{e}^{BN}\right)}{d\lambda }+\left({c}_{1}-{c}_{2}\right)\frac{d{Q}^{BN}}{d\lambda }=ph\left({Q}^{BN},{e}^{BN}\right)-\left(\lambda p+{c}_{1}-{c}_{2}\right)\frac{p}{2a}-\frac{1-F\left({Q}^{BN}-{e}^{BN}\right)}{f\left({Q}^{BN}-{e}^{BN}\right)}\frac{\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)p\left({c}_{1}-{c}_{2}\right)+p\left(w+{c}_{1}-s\right)}{{\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)}^{2}}\). Based on the IGFR assumption, we have \(\frac{d\left({Q}^{BN}-{e}^{BN}\right)}{d\lambda }=-\frac{p\left(w+{c}_{1}-s\right)}{f\left({Q}^{BN}-{e}^{BN}\right){\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)}^{2}}<0\) and \(\frac{dh\left({Q}^{BN}-{e}^{BN}\right)}{d\lambda }=-\frac{p}{2a}-\frac{1-F\left({Q}^{BN}-{e}^{BN}\right)}{f\left({Q}^{BN}-{e}^{BN}\right)}\frac{p\left(w+{c}_{1}-s\right)}{{\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)}^{2}}<0\). Hence, we have \(\frac{{d}^{2}E\left({\pi }_{p}\right)}{d{\lambda }^{2}}<0\) and \({\lambda }^{BN}\) satisfies \(\frac{dE\left({\pi }_{p}\right)}{d\lambda }=ph\left({Q}^{BN},{e}^{BN}\right)+\lambda p\frac{dh\left({Q}^{BN},{e}^{BN}\right)}{d\lambda }+\left({c}_{1}-{c}_{2}\right)\frac{d{Q}^{BN}}{d\lambda }=0\). Q.E.D.

Proof of Proposition 2

In scenario BN, we first solve the optimal effort level and order quantity of the OR under revenue-cost sharing contract and have \({e}^{*}=\frac{x\left(1-\lambda \right)p-w\left(1-y\right)-{c}_{1}}{2a(1-y)}\) and \({Q}^{*}={F}^{-1}\left[\frac{w\left(1-y\right)+{c}_{1}-x\left(1-\lambda \right)p}{xs-x\left(1-\lambda \right)p}\right]+\frac{x\left(1-\lambda \right)p-w\left(1-y\right)-{c}_{1}}{2a(1-y)}\). From the results in Lemma 1, we solve the equations \({e}^{*}={e}^{C}\) and \({Q}^{*}={Q}^{C}\),we can obtain that \(x=\frac{{c}_{1}\left(p-s\right)}{\left(1-\lambda \right)p\left(p-s\right)-\left(p-{c}_{2}\right)\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)}\) and \(y=\frac{\left(1-\lambda \right)p\left(p-s\right)-\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)\left(p+{c}_{1}-{c}_{2}\right)}{\left(1-\lambda \right)p\left(p-s\right)-\left(p-{c}_{2}\right)\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)}\). Q.E.D.

Proof of Corollary 1

From the revenue-cost sharing contract in scenario BN, we have\(\frac{\partial {x}^{BN}}{\partial s}=-\frac{{\lambda }^{BN}p{c}_{1}\left(p-{c}_{2}\right)}{{\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BN}\right)p\left(p-s\right)-\left(p-{c}_{2}\right)\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BN}\right)-s\right)\right)}^{2}}<0\),\(\frac{\partial {x}^{BN}}{\partial p}=\frac{{\lambda }^{BN}s{c}_{1}\left(s-{c}_{2}\right)}{{\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BN}\right)p\left(p-s\right)-\left(p-{c}_{2}\right)\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BN}\right)-s\right)\right)}^{2}}\),\(\frac{\partial {x}^{BN}}{\partial {\lambda }^{BN}}=-\frac{\left(p-s\right)p{c}_{1}\left(s-{c}_{2}\right)}{{\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BN}\right)p\left(p-s\right)-\left(p-{c}_{2}\right)\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BN}\right)-s\right)\right)}^{2}}\),\(\frac{\partial {y}^{BN}}{\partial p}=-\frac{{\lambda }^{BN}\left(1-{\lambda }^{BN}\right)ps{c}_{1}}{{\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BN}\right)p\left(p-s\right)-\left(p-{c}_{2}\right)\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BN}\right)-s\right)\right)}^{2}}<0,\frac{\partial {y}^{BN}}{\partial {\uplambda }^{BN}}=\frac{ps{c}_{1}\left(p-s\right)}{{\left(\left(1-{\uplambda }^{BN}\right)p\left(p-s\right)-\left(p-{c}_{2}\right)\left(\left(1-{\uplambda }^{BN}\right)-s\right)\right)}^{2}}>0\), and\(\frac{\partial {y}^{BN}}{\partial s}=\frac{{\lambda }^{BN}\left(1-{\lambda }^{BN}\right){p}^{2}{c}_{1}}{{\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BN}\right)p\left(p-s\right)-\left(p-{c}_{2}\right)\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BN}\right)-s\right)\right)}^{2}}>0\). Hence, the results in Corollary 1 can be obtained. Q.E.D.

Proof of Proposition 3

In scenario BA, the OR’s objective is to maximize its Mean-CVaR objective function. From the first-order derivative of \({\pi }_{mc}\) with respect to \(v\) ,we obtain\(\frac{\partial {\pi }_{mc}}{\partial v}=\left(1-t\right)(1-\frac{1}{1-\beta }({\int }_{0}^{\mathit{min}\left(\frac{v+\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)Q+a{e}^{2}-sQ}{\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s}-e,Q-e\right)}f\left(x\right)dx+{\int }_{Q-e}^{\infty }kf\left(x\right)dx))\). Among them,\(k=1\), if\(v>\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)Q-\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)Q-a{e}^{2}\), and\(k=0\), if\(v\le \left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)Q-\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)Q-a{e}^{2}\). Hence, we have\(\frac{\partial {\pi }_{mc}}{\partial v}=\left(1-t\right)(1-\frac{1}{1-\beta }({\int }_{0}^{\mathit{min}\left(\frac{v+\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)Q+a{e}^{2}-sQ}{\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s}-e,Q-e\right)}f(x)d(x)))\), if\(v<\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)pQ-\left(\omega +{c}_{1}\right)Q-a{e}^{2}\);\(\frac{\partial {\pi }_{mc}}{\partial v}=-\left(1-t\right)\frac{\beta }{1-\beta }\), if\(v\ge \left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)pQ-\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)Q-a{e}^{2}\).

If\(\frac{\partial {\pi }_{mc}}{\partial v}\ge 0\), we have \(\beta \le \frac{w+{c}_{1}-s}{t\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)}\) and the optimal \(v\) is \({v}^{*}=\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)Q-\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)Q-a{e}^{2}\). Substituting \({v}^{*}\) into\({\pi }_{mc}\), we have\({\pi }_{mc}\left({v}^{*}\right)=tE\left({\pi }_{r}\right)+\left(1-t\right)\left(\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)Q-\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)Q-a{e}^{2}\!-\!\frac{1}{1\!-\!\beta }{\int }_{0}^{Q-e}\left(\left(1\!-\!{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p\!-\!s\right)\left(x\!+\!e\right)f\left(x\right)dx\right)\). From the second-order derivative, we obtain\(\frac{{\partial }^{2}{\pi }_{mc}\left({v}^{*}\right)}{d{Q}^{2}}=-\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)\frac{1-t\beta }{1-\beta }f\left(Q-e\right)<0\). By solving\(\frac{\partial {\pi }_{mc}\left({v}^{*}\right)}{dQ}=0\), we have\({Q}_{1}^{BA}={F}^{-1}\left(\frac{\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)\right)\left(1-\beta \right)}{\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)\left(1-t\beta \right)}\right)+e\).

If \(\frac{\partial {\pi }_{mc}}{\partial v}<0\), the results can be derived in the same way. Substituting \({Q}^{BA}\) into \({\pi }_{mc}({v}^{*})\), we obtain that the OR’s optimal effort level on sales is \(e^{BA} = \frac{{\left( {1 - \lambda^{BA} } \right)p - w{-}c_{1} }}{2a}\) if \(\beta >\frac{w+{c}_{1}-s}{t\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)}\) or \(\beta \le \frac{w+{c}_{1}-s}{t\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)}\). In sum, we have \({e}^{BA}=\frac{\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-w-{c}_{1}}{2a}\), \({Q}_{1}^{BA}={F}^{-1}\left(\frac{\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)\right)\left(1-\beta \right)}{\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)\left(1-t\beta \right)}\right)+\frac{\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-w-{c}_{1}}{2a}\) if \(\beta \le \frac{w+{c}_{1}-s}{t\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)}\) and \({Q}_{2}^{BA}={F}^{-1}\left(1+\frac{s-w-{c}_{1}}{t\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)}\right)+\frac{\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-\omega -{c}_{1}}{2a}\) if \(\beta >\frac{w+{c}_{1}-s}{t\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)}\).

With respect to the results in Proposition 3, if \(\beta \le \frac{w+{c}_{1}-s}{t\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)}\),we have \(\frac{\partial E\left({\pi }_{p}\right)}{\partial \lambda }=ph\left({Q}_{1}^{BA},{e}_{1}^{BA}\right)-\lambda p\left(\frac{p}{2a}+\frac{1-F\left({Q}_{1}^{BA}-{e}_{1}^{BA}\right)}{f\left({Q}_{1}^{BA}-{e}_{1}^{BA}\right)}\frac{p\left(w-s\right)}{{\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)}^{2}}\frac{1-\beta }{1-t\beta }\right)\) and \(\frac{\partial h\left({Q}_{1}^{BA},{e}_{1}^{BA}\right)}{d\lambda }=-\frac{p}{2a}-\frac{1-F\left({Q}_{1}^{BA}-{e}_{1}^{BA}\right)}{f\left({Q}_{1}^{BA}-{e}_{1}^{BA}\right)}\frac{p\left(w-s\right)}{{\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)}^{2}}\frac{1-\beta }{1-t\beta }<0\). Based on the IGFR assumption and the results that \(\frac{\partial \left({Q}_{1}^{BA}-{e}_{1}^{BA}\right)}{d\lambda }=-\frac{1}{f\left({Q}_{1}^{BA}-{e}_{1}^{BA}\right)}\frac{p\left(w-s\right)}{{\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)}^{2}}\frac{1-\beta }{1-t\beta }<0\), we have \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}h\left({Q}_{1}^{BA},{e}_{1}^{BA}\right)}{\partial {\lambda }^{2}}<0\), \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}{Q}_{1}^{BA}}{\partial {\lambda }^{2}}=\frac{{\partial }^{2}\left({Q}_{1}^{BA}-{e}_{1}^{BA}\right)}{\partial {\lambda }^{2}}<0\), and \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}E\left({\pi }_{p}\right)}{\partial {\lambda }^{2}}<0\). Therefore, the optimal usage fee rate satisfies \(\frac{dE\left({\pi }_{p}\right)}{d\lambda }=ph\left({Q}_{1}^{BA},{e}_{1}^{BA}\right)+{\lambda }^{BA}p\frac{dh\left({Q}_{1}^{BA},{e}_{1}^{BA}\right)}{d\lambda }+\left({c}_{1}-{c}_{2}\right)\frac{d{Q}_{1}^{BA}}{d\lambda }=0\). If \(\beta >\frac{w+{c}_{1}-s}{t\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s\right)}\), the results can be derived in the same way. Q.E.D.

Proof of Corollary 2

In Proposition 1 and Proposition 3, we show that the optimal usage fee rate satisfies\(\frac{dE\left[{\pi }_{p}\right]}{d\lambda }=0\). Let \(V\left(\lambda ,t\right)=\frac{dE\left({\pi }_{p}\right)}{d\lambda }=0\),and we have \(\frac{\partial \lambda }{\partial t}=-\frac{\frac{\partial V\left(\lambda ,t\right)}{\partial t}}{\frac{\partial V\left(\lambda ,t\right)}{\partial \lambda }}\), in which\(\frac{\partial V\left(\lambda ,t\right)}{\partial t}=\frac{\partial V\left(\lambda ,t\right)}{\partial Q}\frac{\partial Q}{\partial t}\). Given a \(\lambda \),it is obvious that \(\frac{\partial {Q}^{BA}}{\partial t}>0\) and \({e}^{BA}\) is independent of\(t\). Note that we have\(\frac{\partial h\left(Q,e\right)}{\partial Q}=1-F\left(Q-e\right)>0\),\(\frac{dh\left(Q,e\right)}{d\lambda }=-\frac{p}{2a}-\frac{1-F\left(Q-e\right)}{f\left(Q-e\right)}\frac{p\left(w-s\right)}{{\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)}^{2}}\), \(\frac{dQ}{d\lambda }=-\frac{p}{2a}-\frac{1-F\left(Q-e\right)}{f\left(Q-e\right)}\frac{p}{\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s}\) and the IGFR assumption, which lead to the results that \(\frac{dh\left(Q,e\right)}{d\lambda }\) and \(\frac{dQ}{d\lambda }\) increase in\(Q\). Hence, we have\(\frac{\partial V\left(\lambda ,t\right)}{\partial Q}>0\), \(\frac{\partial V\left(\lambda ,t\right)}{\partial t}=\frac{\partial V\left(\lambda ,t\right)}{\partial Q}\frac{\partial Q}{\partial t}>0\) and then\(\frac{\partial \lambda }{\partial t}>0\). It is obvious that \({Q}^{BA}={Q}^{BN}\) and \({e}^{BA}={e}^{BN}\) if \(t \to 1\). Based on the results that\(\frac{\partial \lambda }{\partial t}>0\),we have\({\lambda }^{BA}\le {\lambda }^{BN}\). Q.E.D.

Proof of Propositions 4, 6, and 8

Similar to the Proof of Proposition 2, the results are immediate. Q.E.D.

Proof of Proposition 5

Similar to the Proof of Lemma 1, we can easily obtain the results of \({e}^{EN}\) and \({Q}^{EN}\).

By solving the first-order and second-order derivative of \(E\left[{\pi }_{p}\right]\) on\(\lambda \), we have \(\frac{\partial E\left({\pi }_{p}^{EN}\right)}{\partial \lambda }=ph\left({Q}^{EN},{e}^{EN}\right)+p{\lambda }^{EN}\frac{\partial h\left({Q}^{EN},{e}^{EN}\right)}{\partial {\lambda }^{EN}}+\left({c}_{1}-{c}_{2}\right)\frac{\partial {Q}^{EN}}{\partial {\lambda }^{EN}}+\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)r\frac{\partial {Q}^{EN}}{\partial {\lambda }^{EN}}+2a{e}^{EN}r\frac{\partial {e}^{EN}}{\partial {\lambda }^{EN}}\) and\(\frac{{\partial }^{2}E\left({\pi }_{p}\right)}{\partial {\lambda }^{2}}=p\frac{\partial h\left({Q}^{EN},{e}^{EN}\right)}{\partial \lambda }+p\left(\frac{\partial {Q}^{EN}}{\partial \lambda }-\frac{\partial {e}^{EN}}{\partial \lambda }\right)\left(1-F\left({Q}^{EN}-{e}^{EN}\right)\right)+p\frac{\partial {e}^{EN}}{\partial \lambda } +{\lambda }^{EN}p\frac{{\partial }^{2}h\left({Q}^{EN},{e}^{EN}\right)}{\partial {\lambda }^{2}}+\left({c}_{1}-{c}_{2}\right)\frac{{\partial }^{2}{Q}^{EN}}{\partial {\lambda }^{2}}+\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)r\frac{{\partial }^{2}{Q}^{EN}}{\partial {\lambda }^{2}}+\frac{r{p}^{2}}{2a{\left(1+r\right)}^{2}}\). Based on the results that \(\frac{\partial {Q}^{EN}}{\partial \lambda }=-\frac{p\left(\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)\left(1+r\right)-s\right)}{{\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)}^{2}f\left({Q}^{EN}-{e}^{EN}\right)}-\frac{p}{2a\left(1+r\right)}=-\frac{p\left(1-F\left({Q}^{EN}-{e}^{EN}\right)\right)}{\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)f\left({Q}^{EN}-{e}^{EN}\right)}-\frac{p}{2a\left(1+r\right)}<0\) and\(\frac{\partial \left({Q}^{EN}-{e}^{EN}\right)}{\partial \lambda }=-\frac{p\left(\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)\left(1+r\right)-s\right)}{{\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)}^{2}f\left({Q}^{EN}-{e}^{EN}\right)}<0\), we have \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}{Q}^{EN}}{\partial {\lambda }^{2}}<0\), \(\frac{\partial {e}^{EN}}{\partial \lambda }=-\frac{p}{2a\left(1+r\right)}<0\) and\(\frac{\partial h\left({Q}^{EN},{e}^{EN}\right)}{\partial \lambda }=-\frac{p\left(\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)\left(1+r\right)-s\right)\left(1-F\left({Q}^{EN}-{e}^{EN}\right)\right)}{{\left(\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s\right)}^{2}f\left({Q}^{EN}-{e}^{EN}\right)}-\frac{p}{2a\left(1+r\right)}<0\). In addition, based on the results that \(p\frac{\partial {e}^{EN}}{\partial \lambda }+\frac{r{p}^{2}}{2a{\left(1+r\right)}^{2}}=-\frac{r{p}^{2}}{2a{\left(1+r\right)}^{2}}<0\) and the IGFR assumption, we have\(\frac{{\partial }^{2}E\left({\pi }_{p}\right)}{\partial {\lambda }^{2}}<0\). Therefore, the usage fee rate \({\lambda }^{EN}\) satisfies\(\frac{\partial E{\left({\pi }_{p}\right)}^{EN}}{\partial \lambda }=ph\left({Q}^{EN},{e}^{EN}\right)+p{\lambda }^{EN}\frac{\partial h\left({Q}^{EN},{e}^{EN}\right)}{\partial {\lambda }^{EN}}+\left({c}_{1}-{c}_{2}\right)\frac{\partial {Q}^{EN}}{\partial {\lambda }^{EN}}+\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)r\frac{\partial {Q}^{EN}}{\partial {\lambda }^{EN}}+2a{e}^{EN}r\frac{\partial {e}^{EN}}{\partial {\lambda }^{EN}}=0\).

Let\(\left(\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)Q+a{e}^{2}-B\right)\left(1+\overline{r }\right)=\left(1-\lambda \right)px+s\left(Q-\left(x+e\right)\right)\), we have \(x=L=\frac{\left(\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)Q+a{e}^{2}-B\right)\left(1+\overline{r }\right)-sQ}{\left(1-{\lambda }^{BA}\right)p-s}-e\), and the OR declares bankruptcy if\(x<L\). When the capital-constrained OR borrows capital from an EP in a perfectly competitive capital market, the EP can only get the market risk-free interest income by setting a suitable loan interest rate\(\overline{r }\). Hence, we have\(\mathrm{min}\left[\left(\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)Q+a{e}^{2}-B\right)\left(1+\overline{r }\right),\left(1-\lambda \right)p\mathrm{min}\left(Q+e,x\right)+s{\left(Q-\left(x+e\right)\right)}^{+}\right]=\left(\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{EN}\right)p-s\right)e+sQ\right)F\left(L\right)+\left(\left(1-{\lambda }^{EN}\right)p-s\right){\int }_{0}^{L}xf\left(x\right)dx+\left(\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)Q+a{e}^{2}-B\right)\left(1+\overline{r }\right)\left(1-F\left(L\right)\right)=\left(\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)Q+a{e}^{2}-B\right)\left(1+r\right)\). Hence, \(\overline{r }\) satisfies\({A}_{1}+{A}_{2}+{A}_{3}=\left(\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)Q+a{e}^{2}-B\right)\left(1+r\right)\), in which\({A}_{1}=\left(\left(\left(1-\uplambda \right)p-s\right){e}^{EN}+s{Q}^{EN}\right)F\left(L\right)\),\({A}_{2}=\left(\left(1-\uplambda \right)p-s\right){\int }_{0}^{L}xf\left(x\right)dx\), \({A}_{3}=\left(\left(w+{c}_{1}\right){Q}^{EN}+a{\left({e}^{EN}\right)}^{2}-B\right)\left(1+\overline{r }\right)\left(1-F\left(L\right)\right)\) and\(L=\frac{\left(\left(w+{c}_{1}\right){Q}^{EN}+a{\left({e}^{EN}\right)}^{2}-B\right)\left(1+\overline{r }\right)-s{Q}^{EN}}{\left(1-\lambda \right)p-s}-{e}^{EN}\). Q.E.D.

Proof of Corollary 3

We have \(\frac{\partial \overline{r}}{\partial r }=\frac{1}{1-F\left(L\right)}\) and \(\frac{\partial \overline{r}}{\partial B }=-\frac{1+r-\left(1+\overline{r }\right)\left(1-F\left(L\right)\right)}{\left(\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)Q+a{e}^{2}-B\right)\left(1-F\left(L\right)\right)}\). Then the results can be directly derived. Q.E.D.

Proof of Proposition 7

Similar to the proof of Proposition 3, the results are immediate. Q.E.D.

Proof of Corollary 4

Similar to the Proof of Corollary 6, the results are immediate. Q.E.D.

Proof of Proposition 9

Similar to the proof of Proposition 5, the results are immediate. Q.E.D.

Proof of Corollary 5

From Propositions 5 and 9, if \(={r}_{a}\), we substitute \({\lambda }^{B}\) into \(\frac{\partial E[{\pi }_{p}^{EN}]}{\partial \lambda }\) and have \(\frac{\partial E\left[{\pi }_{p}^{EN}\right]}{\partial \lambda }{|}_{\lambda ={\lambda }^{B}}=\left[\left(w+{c}_{1}\right)r\frac{\partial {Q}^{EN}}{\partial \lambda }+2a{e}^{EN}r\frac{\partial {e}^{EN}}{\partial \lambda }\right]{|}_{\lambda ={\lambda }^{B}}<0\) because \(\frac{\partial {Q}^{EN}}{\partial \lambda }<0\) and\(\frac{\partial {e}^{EN}}{\partial \lambda }<0\). With the results that \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}E\left[{\pi }_{p}^{EN}\right]}{\partial {\lambda }^{2}}<0\) and\(\frac{\partial E\left[{\pi }_{r}^{B}\right]}{\partial \lambda }<0\), we have \({\lambda }^{EN}\le {\lambda }^{B}\) and\(E\left[{\pi }_{r}^{EN}\right]\ge E\left[{\pi }_{r}^{B}\right]\). Q.E.D.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tao, Y., Yang, R., Zhuo, X. et al. Financing the capital-constrained online retailer with risk aversion: coordinating strategy analysis. Ann Oper Res 331, 321–349 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-022-04632-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-022-04632-4