Abstract

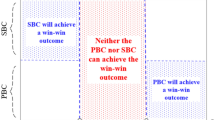

This paper examines a unique selling strategy, group buying on a social E-commerce platform. We proposed a framework on how to design a group buying strategy in the presence of different social network attributes (different structures, different referral costs, and different network externalities) to examine the following questions: (1) How will the group buying threshold depend on consumer referrals under social networks attributes? (2) What determines the optimal group buying threshold and the group buying price in different social networks attributes? (3) What is the efficiency of group buying with threshold compared to the traditional group buying without referrals and referral reward program? We show that the threshold causes an induction effect, but this induction effect is meaningless when the externality is considerably greater than the referral cost. Moreover, we also show that higher referral costs and prices result in a larger threshold when referral cost and externality have approximate impact on the utility of the focal consumer. We also find that the firm cannot set a low price of group buying even when the referral cost is much higher than the network externality. Finally, we present a sufficient condition that a group buying strategy is better than a referral reward strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Acquisti, A., & Varian, H. R. (2005). Conditioning prices on purchase history. Marketing Science,24(3), 367–381.

Anand, S. K., & Aron, R. (2003). Group-buying on the web: A comparison of price discovery mechanisms. Management Science,49(11), 1546–1562.

Aral, S., Muchnik, L., & Sundararajan, A. (2013). Engineering social contagions: Optimal network seeding in the presence of homophily. Network Science,1(2), 125–153.

Biyalogorsky, E., Gerstner, E., & Libai, B. (2001). Consumer referral management: Optimal reward programs. Marketing Science,20(1), 82–95.

Boon, E. (2013). A qualitative study of consumer-generated videos about daily deal web sites. Psychology and Marketing,30(10), 843–849.

Borges, A., Chebat, J. C., & Babin, B. J. (2010). Does a companion always enhance the shopping experience? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,17(4), 294–299.

Busalim, A. H., & Hussin, A. R. C. (2016). Understanding social commerce: A systematic literature review and directions for further research. International Journal of Information Management,36(6), 1075–1088.

Buttle, F. A. (1998). Word of mouth: Understanding and managing referral marketing. Strategic Marketing,6(3), 241–254.

Chatterjee, K., & Dutta, B. (2016). Credibility and strategic learning in networks. International Economic Review,57(3), 759–786.

Che, Yeon-Koo, & Gale, Ian. (1997). Buyer alliances and managed competition. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy,6(1), 175–200.

Chen, J. (2013). Emerging e-commerce, pricing, multi-channel coordination and supply chain optimization (pp. 110–111). Beijing: Tsinghua University Press.

Chen, J., Guan, L., & Cai, X. (2017). Analysis on buyers’ cooperative strategy under group-buying price mechanism. Journal of Industrial and Management Optimization,9(2), 291–304.

Chen, Y., & Xie, J. (2008). Online consumer review: Word-of-mouth as a new element of marketing communication mix. Management Science,54(3), 477–491.

Chen, Z., Liang, X., Wang, H., & Yan, H. (2012). Inventory rationing with multiple demand classes: The case of group buying. Operations Research Letters,40(5), 404–408.

Chu, S. C., & Kim, Y. (2011). Determinants of consumer engagement in electronic word-of-mouth (ewom) in social networking sites. International Journal of Advertising,30(1), 47.

Cui, Y., Mou, J., & Liu, Y. (2018). Knowledge mapping of social commerce research: A visual analysis using citespace. Electronic Commerce Research,18(4), 837–868.

Dan, H. R., Fay, S. A., & Xie, J. (2014). Probabilistic selling vs. markdown selling: Price discrimination and management of demand uncertainty in retailing. International Journal of Research in Marketing,31(2), 147–155.

Duffett, R. G. (2015). The influence of Facebook advertising on cognitive attitudes amid generation y. Electronic Commerce Research,15(2), 243–267.

Deng, S., Jiang, X., & Li, Y. (2017). Optimal price and maximum deal size on group-buying websites for sellers with finite capacity. International Journal of Production Research,2, 1–16.

Du, L., & Feng, J. (2009). Optimal threshold in the group-buying auction with replenishment postponement. In International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (pp. 181–184). IEEE.

Fay, S., & Xie, J. (2008). Probabilistic goods: A creative way of selling products and services. Marketing Science,27(4), 674–690.

Fay, S., & Xie, J. (2010). The economics of buyer uncertainty: Advance selling vs. probabilistic selling. Marketing Science,29(6), 1040–1057.

Gao, F., & Chen, J. (2015). The role of discount vouchers in market with customer valuation uncertainty. Production and Operations Management,24(4), 665–679.

Hajli, M. N. (2014). The role of social support on relationship quality and social commerce. Technological Forecasting and Social Change,87(1), 17–27.

He, W., Zha, S., & Li, L. (2013). Social media competitive analysis and text mining: A case study in the pizza industry. International Journal of Information Management,33(3), 464–472.

Hu, M., Shi, M., & Wu, J. (2013). Simultaneous vs. sequential group-buying mechanisms. Management Science,59(12), 2805–2822.

Ilan, L., Sadler, E., & Varshney, L. R. (2017). Consumer referral incentives and social media. Management Science,63(10), 3514–3529.

Jing, X., & Xie, J. (2012). Group-buying: A new mechanism for selling through social interactions. Management Science,57(8), 1354–1372.

Kang, J. Y. M., & Johnson, K. K. P. (2015). F-Commerce platform for apparel online social shopping. International Journal of Information Management,35(6), 691–701.

Katz, M., & Shapiro, C. (1985). Network externalities, competition, and compatibility. The American Economic Review,75(3), 424–440.

Kauffman, R. J., & Wang, B. (2001). New buyers’ arrival under dynamic pricing market microstructure: The case of group-buying discounts on the internet. Journal of Management Information Systems,18(2), 157–188.

Ke, C., Yan, B., & Xu, R. (2017). A group-buying mechanism for considering strategic consumer behavior. Electronic Commerce Research,17(4), 1–32.

Kim, N., & Kim, W. (2018). Do your social media lead you to make social deal purchases? Consumer-generated social referrals for sales via social commerce. International Journal of Information Management,39, 38–48.

Kumar, V., Petersen, A., & Leone, R. (2007). How valuable is word of mouth? Harvard Business Review,85(10), 139–144.

Li, C., Chawla, S., Rajan, U., & Sycara, K. P. (2004). Mechanism design for coalition formation and cost sharing in group buying markets. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 3(4), 341–354.

Luo, X. (2005). How does shopping with others influence impulsive purchasing? Journal of Consumer Psychology,15(4), 288–294.

Ng, M. (2016). Factors influencing the consumer adoption of Facebook: A two-country study of youth markets. Computers in Human Behavior,54(C), 491–500.

Sundararajan, A. (2007). Local network effects and complex network structure. B. E. J. Economic Theory,7(1), Article 46.

Wang, J. C., & Chang, C. H. (2013). How online social ties and product-related risks influence purchase intentions: A Facebook experiment. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Wu, J., Shi, M., & Hu, M. (2015). Threshold effects in online group buying. Social Science Electronic Publishing,61(9), 2025–2040.

Xie, J., & Steven, M. S. (2001). Electronic tickets, smart cards, and online prepayments: When and how to advance sell. Marketing Science,20(3), 219–243.

Yi, L., & Sutanto, J. (2011). Social sharing behavior under E-commerce context. In Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (vol. 120).

Zhang, G., Shang, J., & Yildirim, P. (2016). Optimal pricing for group buying with network effects. Omega,63, 69–82.

Zhang, P., Zhou, L., & Zimmermann, H. D. (2013). Social commerce research: An integrated view. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications,12(2), 61–68.

Zhao, M., & Xie, J. (2013). Effects of social and temporal distance on consumers’ responses to peer recommendations. Journal of Marketing Research,48(3), 486–496.

Zhou, G., Xu, K., & Liao, S. S. (2013). Do starting and ending effects in fixed-price group-buying differ? Electronic Commerce Research and Applications,12(2), 78–89.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by: (i) the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants 71671061 and 71420107027; (ii) the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province in China under Grant 2018JJ1003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

The proof of Proposition 2.

When \(\;p_{1} < \frac{c - \delta }{c}b\), note \(f\left( {\underline{x} } \right) = \frac{{b\left( {b - p_{1} } \right)}}{{\left( {b - \delta \underline{x} } \right)^{2} }}\int\limits_{{\underline{x} }}^{m} {g\left( n \right)dn} - \left( {\frac{{b - p_{1} }}{{b - \delta \underline{x} }}\underline{x} + 1} \right)g\left( {\underline{x} } \right)\). \(f\left( 0 \right) = \frac{{b - p_{1} }}{b} > 0\),\(f\left( m \right) = - \left( {\frac{{b - p_{1} }}{b - \delta m}m + 1} \right)g\left( m \right) < 0\). Thus, So the function in Eq. (5) has the increase and decrease in \(\left[ { 0 ,m} \right]\), and function in Eq. (5) is increasing at first. Suppose \(f\left( {x^{ * } } \right) = 0\). If \(0\le x^{ * } \le \frac{{bc - \sqrt {bc\left( {bc - 4b\delta + 4bp_{1} } \right)} }}{2\delta c}\), the maximum point is \(x^{ * }\). But if \(x^{ * } > \frac{{bc - \sqrt {bc\left( {bc - 4b\delta + 4bp_{1} } \right)} }}{2\delta c}\), the maximum point must be \(\frac{{bc - \sqrt {bc\left( {bc - 4b\delta + 4bp_{1} } \right)} }}{2\delta c}\). This is an extreme case, and it is impossible to react much to the association between the various external factors, and we are temporarily ignoring this situation. Therefore, when \(p_{1} < \frac{c - \delta }{c}b\), the optimal threshold is in \(\left( {1,\frac{{\left( {b - p} \right)\left( {bc - \sqrt {bc\left( {bc - 4b\delta + 4bp_{1} } \right)} } \right)}}{{\delta \left( {bc + \sqrt {bc\left( {bc - 4b\delta + 4bp_{1} } \right)} } \right)}}} \right)\) should satisfy Eq. (8).

We can proof the conclusion when \(p_{1} \ge \hbox{max} \left( {\frac{c - \delta }{c}b,\frac{\delta - c}{\delta }b} \right)\) in same way.

The proof of Proposition 6.

First, we consider the first subsection of Eq. (10), we note it as Eqs. (20) and (21):

Then, according to the first derivative, we can easily know that both the functions in two subsections are increased first and then reduced in \(\left( { 0 ,\frac{p}{\delta }} \right)\). Therefore, it is obvious that the maximum point of Eq. (10) can only be taken at the maximum point of Eq. (20), the maximum point of Eq. (21), and the point of discontinuity \(\frac{c - \delta }{c}b\).

According to the first derivative of Eq. (11), we got the maximum point of the Eq. (20) is \(\frac{b}{ 2} + \frac{{b - \delta \underline{x} }}{{2\underline{x} }}\), which is bigger than \(\frac{b}{2}\)

When \(c > 2\delta\), \(\frac{c - \delta }{c}b > \frac{b}{2}\), and the maximum point of Eq. (21) is bigger than \(\frac{c - \delta }{c}b\),

So, the Proposition 6 can be proved.

The proof of Proposition 7.

- (1)

When \(\delta < c\).

If \(p_{1} < \frac{c - \delta }{c}b\), compare Eq. (11) to (5). Note \(F\left( {\underline{x} } \right) = Q\left( {\underline{x} } \right) - Q_{T} = \int\limits_{{\underline{x} }}^{m} {\left( {\frac{{b - p_{1} }}{{b - \delta \underline{x} }}\underline{x} + 1} \right)g\left( n \right)dn} - 1\). Clearly, \(F\left( 0 \right) = 0\). \(\frac{{\partial F\left( {\underline{x} } \right)}}{{\partial \underline{x} }} = \frac{{b\left( {b - p_{1} } \right)}}{{\left( {b - \delta \underline{x} } \right)^{2} }}\int\limits_{{\underline{x} }}^{m} {g\left( n \right)dn} - \left( {\frac{{b - p_{1} }}{{b - \delta \underline{x} }}\underline{x} + 1} \right)g\left( {\underline{x} } \right)\), \(\left. {\frac{{\partial F\left( {\underline{x} } \right)}}{{\partial \underline{x} }}} \right|_{{\underline{x} = 0}} = \frac{{b - p_{1} }}{b} > 0\), thus, the function in Eq. (5) is increasing at first. So, we can always find a \(\underline{x}\) makes \(Q\left( {\underline{x} } \right) > Q_{T}\), even if the \(\underline{x}\) is not optimal.

If \(p_{1} > \frac{c - \delta }{c}b\), we should compare Eq. (11) to (6). From the present of Eqs. (5) and (6). We can easily see that \(\left( {M + 1} \right)\int\limits_{{\underline{x} }}^{{\overline{x} }} {g\left( n \right)} dn + \int\limits_{{\overline{x} }}^{m} {\left( {\frac{{b - p_{1} }}{b - \delta n}n + 1} \right)} g\left( n \right)dn \ge \int\limits_{{\underline{x} }}^{m} {\left( {M + 1} \right)g\left( n \right)dn}\) for any \(\underline{x}\). Thus, the above conclusion is also established when \(p_{1} > \frac{c - \delta }{c}b\).

When \(\delta \ge c\) and \(p_{1} > \frac{c - \delta }{c}b\), compare Eq. (12) to (6). Note \(F\left( {\underline{x} } \right) = Q\left( {\underline{x} } \right) - Q_{T}\)

Clearly, \(F\left( 0 \right) = 0\), \(\left. {\frac{{\partial F\left( {\underline{x} } \right)}}{{\partial \underline{x} }}} \right|_{{\underline{x} = 0}} = \frac{{b - p_{1} }}{b} > 0\), thus, the function in Eq. (6) is increasing at first. So, we can always find a \(\underline{x}\) makes \(Q\left( {\underline{x} } \right) > Q_{T}\), even if the \(\underline{x}\) is not optimal.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, E., Li, H. Group buying and consumer referral on a social network. Electron Commer Res 20, 21–52 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-019-09357-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-019-09357-4