Abstract

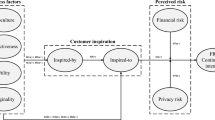

Despite the convenience of facial recognition payment (FRP), many consumers hesitate to use FRP. Drawing on the antecedent-privacy concern-outcome (APCO) macro model, this study investigates antecedents of privacy concerns and privacy fatigue in the context of FRP and how privacy concerns and privacy fatigue influence user’s resistance intention of FRP. A mixed-methods is used to address these issues. A semi-structured interview is first used to identify the antecedents of privacy concerns and privacy fatigue for facial privacy information. According to the research results, we develop research hypotheses and build the research model. By analyzing survey data from 394 respondents using Amos, this study finds that privacy experience, privacy control, privacy policy effectiveness, peer influence, and reputation significantly influence users’ privacy concerns for facial privacy information; in addition, privacy experience, privacy control, and negative media exposure significantly influence users’ privacy fatigue. Moreover, privacy concerns and privacy fatigue are significantly related to users’ resistance intention to FRP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

BBC News. 2019. China facial recognition: Law professor sues wildlife park.https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-50324342.

Xinhua News Agency. 2020. Who’s selling our facial information?http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-07/13/c_1126232239.htm.

Consumer News & Business Channel (CNBC). 2019. San Francisco bans police use of face recognition technology.https://www.cnbc.com/2019/05/15/san-francisco-bans-police-use-of-face-recognition-technology.html.

References

Zhong, Y., Oh, S., & Moon, H. C. (2021). Service transformation under industry 4.0: Investigating acceptance of facial recognition payment through an extended technology acceptance model. Technology in Society, 64, 101515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101515

Liu, Y. L., Yan, W., & Hu, B. (2021). Resistance to facial recognition payment in China: the influence of privacy-related factors. Telecommunications Policy, 45(5), 102115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2021.102155

Iimedia (2019). Facial payment research report in China. https://www.iimedia.cn/c400/66866.html

Allen, K. (2019). China facial recognition: Law professor sues wildlife park.BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-50324342

Maity, S., Abdel-Mottaleb, M., & Asfour, S. S. (2020). Multimodal biometrics recognition from facial video with missing modalities using deep learning. Journal of Information Processing Systems, 16(1), 6–29. https://doi.org/10.3745/JIPS.02.0129

Dibeklioglu, H., Alnajar, F., Salah, A. A., & Gevers, T. (2015). Combining facial dynamics with appearance for age estimation. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 24(6), 1928–1943. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2015.2412377

Dantcheva, A., & Br´emond, F. (2016). Gender estimation based on smile-dynamics. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, 12(3), 719–729. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIFS.2016.2632070

Zhang, W. K., & Kang, M. J. (2019). Factors affecting the use of facial-recognition payment: An example of Chinese consumers. Ieee Access : Practical Innovations, Open Solutions, 7, 154360–154374. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2927705

Smith, H. J., Milberg, S. J., & Burke, S. J. (1996). Information privacy: measuring individuals’ concerns about organizational practices. MIS Quarterly, 20(2), 167–196. https://doi.org/10.2307/249477

Choi, H., Park, J., & Jung, Y. (2018). The role of privacy fatigue in online privacy behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 81(APR.), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.12.001

Cheng, X., Hou, T., & Mou, J. (2021). Investigating perceived risks and benefits of information privacy disclosure in it-enabled ride-sharing. Information & Management, (2), 103450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2021.103450

Smith, H. J., Dinev, T., & Xu, H. (2011). Information privacy research: an interdisciplinary review. MIS Quarterly, 35(4), 989–1016. https://doi.org/10.2307/41409970

Li, L., Lee, K. Y., Chang, Y., Yang, S. B., & Park, P. (2021). IT-enabled sustainable development in electric scooter sharing platforms: focusing on the privacy concerns for traceable information. Information Technology for Development, (2), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2021.1882366

Dinev, T., Bellotto, M., Hart, P., Russo, V., Serra, I., & Colautti, C. (2006). Privacy calculus model in e-commerce – a study of Italy and the United States. European Journal of Information Systems, 15(4), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ejis.3000590

Zhu, M., et al. (2021). Privacy paradox in mHealth applications: an integrated elaboration likelihood model incorporating privacy calculus and privacy fatigue. Telematics and Informatics, 61, 101601

Hargittai, E., & Marwick, A. (2016). “What can I really do?“: explaining the privacy paradox with online apathy. International Journal of Communication, 10, 3737–3757

Venkatesh, V., Brown, S. A., & Bala, H. (2013). Bridging the qualitative-quantitative divide: guidelines for conducting mixed methods research in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 37(1), 21–54. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43825936

Venkatesh, V., Brown, S. A., &Sullivan, Y. W., et al. (2016). Guidelines for conducting mixed-methods research: an extension and illustration. Journal of the Association of Information Systems, 17(7), 435–495. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00433

Galton, F. (1889). Head growth in students at the University of Cambridge. Nature, 40, 318. https://doi.org/10.1038/040318a0

Galton, F. (1910). Numeralised profiles for classification and recognition. Nature, 83, 127–130. https://doi.org/10.1038/083127a0

Morosan, C. (2020). Hotel facial recognition systems: insight into guests’ system perceptions, congruity with selfimage, and anticipated emotions. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 21(1), 21–38

Gao, J., Rong, Y., Tian, X., & Yao, Y. O. (2020). Save time or save face? the stage fright effect in the adoption of facial recognition payment technology. Social Science Electronic Publishing. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3668036

Moriuchi, E. (2021). An empirical study of consumers’ intention to use biometric facial recognition as a payment method. Psychology & Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21495

Ciftci, O., Choi, E., & Berezina, K. (2021). Let’s face it: are customers ready for facial recognition technology at quick-service restaurants? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 95(2), 102941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102941

Xu, Z., Zhang, T., Zeng, Y., Wan, & Wu, W. (2015). March). A secure mobile payment framework based on face authentication. The International Multiconference of Engineers and Computer Scientists

Belanger, F., & Crossler, R. E. (2011). Privacy in the digital age: a review of information privacy research in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 35, 1017–1041. https://doi.org/10.2307/41409971

Bansal, G., & Zahedi, F. M. (2015). Trust violation and repair: the information privacy perspective. Decision Support Systems, 71(mar.), 62–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2015.01.009

Miltgen, C. L., & Smith, H. J. (2015). Exploring information privacy regulation, risks, trust, and behavior. Information & Management, 52(6), 741–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2015.06.006

Ursin, G., Malila, N., Chang-Claude, J., Gunter, M., & Knudsen, G. (2019). Sharing data safely while preserving privacy. The Lancet, 394(10212), 1902. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32603-0

Agozie, D. Q., & Kaya, T. (2021). Discerning the effect of privacy information transparency on privacy fatigue in e-government. Government Information Quarterly, 1, 101601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2021.101601

James, T. L., Wallace, L., Warkentin, M., Kim, B. C., & Collignon, S. E. (2017). Exposing others’ information on online social networks (OSNS): perceived shared risk, its determinants, and its influence on OSN privacy control use. Information & Management, 54(7), 851–865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2017.01.001

Yu, L., Li, H., He, W., Wang, F. K., & Jiao, S. (2019). A meta-analysis to explore privacy cognition and information disclosure of internet users. International Journal of Information Management, 51, 102015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.09.011

Cellary, W., & Rykowski, J. (2015). Challenges of smart industries – privacy and payment in visible versus unseen internet. Government Information Quarterly, 35(4), S17-S23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.08.005

Krishen, A. S., Raschke, R. L., Close, A. G., & Kachroo, P. (2017). A power-responsibility equilibrium framework for fairness: understanding consumers’ implicit privacy concerns for location-based services. Journal of Business Research, 73(APR.), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.12.002

Xu, H., Teo, H. H., Tan, B., & Agarwal, R. (2009). The role of push-pull technology in privacy calculus. Journal of Management Information Systems, 26(3), 135–174. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222260305

Son, J. Y., & Kim, S. S. (2008). Internet users’ information privacy-protective responses: a taxonomy and a nomological model. MIS Quarterly, 32(3), 503–529

Ream, E., & Richardson, A. (1996). Fatigue: a concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 33(5), 519–529

D’Urso, S. C. (2010). Who’s watching us at work? toward a structural–perceptual model of electronic monitoring and surveillance in organizations. Communication Theory, 16(3), 281–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2006.00271.x

Sirkka, L. J., & Dorothy, E. L. (1999). Communication and Trust in Global Virtual Teams. Organization Science, 10(6), 791–815. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2640242

Anthony, D. M., & Krishnamurthy, S. (2002). Internet Seals of Approval: Effects on Online Privacy Policies and Consumer Perceptions[J]. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 36(1), 28–49. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23860158

Moon, Y. (2000). Intimate exchanges: using computers to elicit self-disclosure from consumers. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(4), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1086/209566

Dinev, T., Smith, H. J., McConnell, et al. (2015). Informing privacy research through information systems, psychology, and behavioral economics: thinking outside the “APCO” box. Information Systems Research, 26(4), 639–655. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2015.0600

Lankton, N. K., & Tripp, J. F. (2013). A Quantitative and Qualitative Study of Facebook Privacy using the Antecedent-Privacy Concern-Outcome Macro Model. AMCIS 2013 Proceedings

Califf, C. B., Sarker, S., & Sarker, S. (2020). The bright and dark sides of technostress: a mixed-methods study involving healthcare it. MIS Quarterly, 44(2), 809–856. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2020/14818

Cui, T., Tong, Y., Teo, H. H., & Li, J. (2020). Managing knowledge distance: it-enabled inter-firm knowledge capabilities in collaborative innovation. Journal of Management Information Systems, 37(1), 217–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2019.1705504

Mingers, & John. (2001). Combining IS research methods: towards a pluralist methodology. Information Systems Research, 12(3), 240–259. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23011015

Creswell, J. W. (2002). Research Designs: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-65552003000100015

Plowman, D. A., Baker, L. T., Beck, T. E., Kulkarni, M., Solansky, S. T., & Travis, D. V. (2007). Radical change accidentally: the emergence and amplification of small change. The Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 515–543. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.25525647

Cheng, X., & Macaulay, L. (2014). Exploring individual trust factors in computer mediated group collaboration: a case study approach. Group Decision and Negotiation, 23(3), 533–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-013-9340-z

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308385

Wunderlich, P., Veit, D. J., & Sarker, S. (2019). Adoption of sustainable technologies: a mixed-methods study of german households. MIS Quarterly, 42(2), 673–691. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2019/12112

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (2008). Basics Of Qualitative Research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications

Bansal, G., Zahedi, F., ‘., & Gefen, D. (2010). The impact of personal dispositions on information sensitivity, privacy concern and trust in disclosing health information online. Decision Support Systems, 49(2), 138–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2010.01.010

Yuan, L. (2014). The impact of disposition to privacy, website reputation and website familiarity on information privacy concerns. Decision Support Systems, 57, 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2013.09.018

Nathalie, B., Pattyn, A., et al. (2008). “Psychophysiological investigation of vigilance decrement: Boredom or cognitive fatigue?“. Physiology & Behavior, 93(1–2), 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.09.016

Phelps, J., Nowak, G., & Ferrell, E. (2000). Privacy concerns and consumer willingness to provide personal information. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 19(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.19.1.27.16941

Anić, I. D., Škare, V.; Kursan Milaković, & Ivana (2019). The determinants and effects of online privacy concerns in the context of e-commerce. Electronic Commerce Research & Applications, 36, 100868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2019.100868

Gardner, M., & Steinberg, L. (2005). Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: an experimental study. Developmental Psychology, 41(4), 625–635. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.625

Rubaltelli, E., Scrimin, S., Moscardino, U., Priolo, G., & Buodo, G. (2018). Media exposure to terrorism and people’s risk perception: the role of environmental sensitivity and psychophysiological response to stress. British Journal of Psychology, 109(4), 656–673. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12292

Gu, J., Xu, Y., Xu, H., Zhang, C., & Ling, H. (2016). Privacy concerns for mobile app download: an elaboration likelihood model perspective. Decision Support Systems, 94, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2016.10.002

Acquisti, A., Brandimarte, L., & Loewenstein, G. (2015). Privacy and human behavior in the age of information. Science, 347(6221), 509–514. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa1465

Culnan, M. J. (1993). “How Did They Get My Name?“: An Exploratory Investigation of Consumer Attitudes toward Secondary Information Use. MIS Quarterly, 17(3), 341–363. https://doi.org/10.2307/249775

Culnan, M. J. (1995). Consumer awareness of name removal procedures: Implications for direct marketing. Journal of Direct Marketing, 9(2), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.4000090204

Malhotra, N. K., Kim, S. S., & Agarwal, J. (2004). Internet users’ information privacy concerns (IUIPC): the construct, the scale, and a causal model. Information Systems Research, 15(4), 336–355. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1040.0032

Phelps, J. E., D’Souza, G., & Nowak, G. J. (2001). Antecedents and consequences of consumer privacy concerns: an empirical investigation (p2-17). Journal of Interactive Marketing, 15(4), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.1019

Xu, H., et al. (2012). Effects of Individual Self-Protection, Industry Self-Regulation, and Government Regulation on Privacy Concerns: A Study of Location-Based Services.Information Systems Research, 23(4), 1342–1363,1378,1382–1383. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42004260

Du, S., Keil, M., Mathiassen, L., Shen, Y., & Tiwana, A. (2007). Attention-shaping tools, expertise, and perceived control in it project risk assessment. Decision Support Systems, 43(1), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2006.10.002

Culnan, M. J., & Armstrong, P. K. (1999). Information privacy concerns, procedural fairness, and impersonal trust: an empirical investigation. Organization Science, 10(1), 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.10.1.104

Chang, Y., Wong, S. F., Libaque-Saenz, C. F., & Lee, H. (2018). The role of privacy policy on consumers’ perceived privacy. Government Information Quarterly, 445–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2018.04.002

Liu, C., Marchewka, J. T., Lu, J., & Yu, C. S. (2005). Beyond concern—a privacy-trust-behavioral intention model of electronic commerce. Information & Management, 42(2), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2004.01.002

Huang, S. Y., Yen, D. C., & Irina Popova. (2012). The effect of online privacy policy on consumer privacy concern and trust. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(3), 889–897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.12.008

Balapour, A., Nikkhah, H. R., & Sabherwal, R. (2020). Mobile application security: Role of perceived privacy as the predictor of security perceptions. International Journal of Information Management, 52, 102063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.102063

Tsai, J. Y., Egelman, S., Cranor, L., & Acquisti, A. (2007). The effect of online privacy information on purchasing behavior: an experimental study. Information Systems Research, 22(2), 254–268. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23015560

Riahi-Belkaoui, A., & Pavlik, E. (1992). Accounting for Corporate Reputation. Westport, CT: Quorum Books

Kim, D. J., Ferrin, D. L., & Rao, H. R. (2008). A trust-based consumer decision-making model in electronic commerce: the role of trust, perceived risk, and their antecedents. Decision Support Systems, 44(2), 544–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2007.07.001

Jøsang, A., Ismail, R., & Boyd, C. (2007). A survey of trust and reputation systems for online service provision. Decision Support Systems, 43(2), 618–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2005.05.019

Wermers, R. (1999). Mutual fund herding and the impact on stock prices. The Journal of Finance, 54(2), 581–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00118

Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer Relationships in Adolescence. In L. Steinberg & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of Adolescent Psychology

Liang, H., & Shen, F. (2018). Birds of a schedule flock together: social networks, peer influence, and digital activity cycles. Computers in Human Behavior, 82(may), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.016

Zhu, Z., Wang, J., Wang, X., & Wan, X. (2016). Exploring factors of user’s peer-influence behavior in social media on purchase intention: evidence from qq. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 980–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.037

Hoadley, C. M., Xu, H., Lee, J. J., & Rosson, M. B. (2010). Privacy as information access and illusory control: the case of the Facebook news feed privacy outcry. Electronic Commerce Research & Applications, 9(1–6), 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2009.05.001

Xu, H., Dinev, T., Smith, J., & Hart, P. (2011). Information privacy concerns: linking individual perceptions with institutional privacy assurances. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 12(12), 798–824. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662241111104893

Stone, E. F., Gueutal, H. G., Gardner, D. G., & Mcclure, S. (1983). A field experiment comparing information-privacy values, beliefs, and attitudes across several types of organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68(3), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.68.3.459

Stewart, K. A., & Segars, A. H. (2002). An empirical examination of the concern for information privacy instrument. Information Systems Research, 13(1), 36–49. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23015822

Okazaki, S., Eisend, M., Plangger, K., Ruyter, K. D., & Grewal, D. (2020). Understanding the strategic consequences of customer privacy concerns: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Retailing. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2020.05.007

Bandara, R. J., Fernando, M., & Akter, S. (2021). Construing online consumers’ information privacy decisions: the impact of psychological distance. Information & Management, 58(7), 103497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2021.103497

Choi, B., & Land, L. (2016). The effects of general privacy concerns and transactional privacy concerns on Facebook apps usage. Information & Management, 53(7), 868–877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.02.003

Zhang, X., Liu, S., Chen, X., Wang, L., Gao, B., & Zhu, Q. (2018). Health information privacy concerns, antecedents, and information disclosure intention in online health communities. Information & Management, 55(4), 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2017.11.003

Zoonen, L. V. (2016). Privacy concerns in smart cities. Government Information Quarterly, 33(3), 472–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.06.004

Hopstaken, J. F., Linden, D., Bakker, A. B., & Kompier, M. (2015). A multifaceted investigation of the link between mental fatigue and task disengagement. Psychophysiology, 52(3), 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12339

Slyke, C., Shim, J. T., Johnson, R., & Jiang, J. (2006). Concern for information privacy and online consumer purchasing. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 7(6), 415–444. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00092

Ax, S., & Gregg, V. H.,D Jones (2001). Coping and illness cognitions: chronic fatigue syndrome. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(2), 161–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00031-8

Arkes, H. R., & Blumer, C. (1985). The psychology of sunk cost. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 35(1), 124–140

Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2010). Research methods for business: A skill building approach (5th ed.). UK: Wiley & Sons Ltd

Mittelstaedt, R. A., et al. (1976). Optimal Stimulation Level and the Adoption Decision Process. Journal of Consumer Research, 3(2), 84–94. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2489114

Hair, J., Mathews, M. L., & Mathews, L. R. (2017). PLM-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123

Hair, J., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press

Saprikis, V., & Avlogiaris, G. (2021). Modeling users’ acceptance of mobile social commerce: the case of ‘Instagram checkout’. Electronic Commerce Research, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-021-09499-4

Fraenkel, J. R., & Wallen, N. E. (2000). How to design and evaluate research in education. New York: McGraw-Hill

Davidshofer, K. R., & Murphy, C. O. (2005). Psychological testing: Principles and applications. New Jersey: Pearson/Prentice-Upper Saddle River

Hair, J. F. Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (2013). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson New International: Pearson Education Limited

Bagozzi, R. P. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: a comment. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 375–381. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150979

Gefen, D., Straub, D. W., & Boudreau, M. (2000). Structural equation modeling and regression: guidelines for research practice. Communication of the Association for Information System, 4(7), 1–77. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.00407

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Falk, R. F., & Miller, N. B. (1992). A primer for soft modeling. Akron, OH: University of Akron Press

Li, Y. (2011). Empirical studies on online information privacy concerns: Literature review and an integrative framework. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 28(28), 453–496

Benamati, J. H., Ozdemir, Z. D., & Smith, H. J. (2017). An empirical test of an Antecedents - Privacy Concerns -Outcomes model. Journal of Information Science, 43(5), 583–600

Ioannou, A., Tussyadiah, I., & Yang, L. (2020). Privacy concerns and disclosure of biometric and behavioral data for travel. International Journal of Information Management, 54, 102122

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank National Natural Science Foundation of China(Grant No. 72061147005)and fund for building world-class universities (disciplines) of Renmin University of China (Project No. KYGJA2022002) for providing funding for part of this research. We also thank the Metaverse Research Center of Renmin University of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Datasets

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1: Measurement scales

Appendix 1: Measurement scales

Construct | Item | Content | Resource |

|---|---|---|---|

Privacy experience | PE1 | I was a victim of facial privacy invasion. | [54] |

PE2 | I believe that my facial privacy was invaded in by other people or organizations. | ||

Privacy awareness | PA1 | I am aware of the privacy issues and practices in FRP. | [35] |

PA2 | I follow news and developments about privacy issues and privacy violations regarding FRP. | ||

Privacy control | PC1 | My control of personal facial information lies at the heart of facial privacy. | [64] |

PC2 | I believed that facial privacy is invaded when control is lost or unwillingly reduced as a result of FRP. | ||

Privacy policy effectiveness | PPE1 | With the privacy policy, I believe that my facial information will be kept private and confidential by service providers. | [69] |

PPE2 | I believe that the privacy policy posted by service providers are an effective way to demonstrate their commitments to privacy. | ||

Reputation | RE1 | This service provider of FRP has a good reputation. | [54] |

RE2 | This service provider of FRP has a reputation for offering good products or services. | ||

Peer influence | PI1 | I feel like people around me are worried about facial information disclosure and infringement in FRP. | Self-developed |

PI2 | People around me remind me to protect my facial information from being leaked or infringed. | ||

PI3 | People around me pay attention to the protection of their facial information. | ||

Negative media exposure | NME1 | I often heard or read about the negative news of the company who provides FRP services during the last year. | [11] |

NME2 | I often heard or read about the negative news about facial information disclosure during the last year. | ||

Privacy concerns | PCON1 | I am concerned about providing my facial information because it could be leaked and used in a way I did not foresee. | [35] |

PCON2 | I am concerned about my facial information that is recorded on FRP because it could be used to identify me. | ||

PCON3 | I am concerned that unauthorized parties could use my facial information to impersonate me. | ||

Privacy fatigue | PF1 | I am tired of facial privacy issues. | [10] |

PF2 | It is tiresome for me to care about facial privacy. | ||

Resistance intention | RI1 | I will try NOT to use FRP. | [95] |

RI2 | I will NOT use FRP in the future. | ||

RI3 | I will NOT use FRP if I have alternatives. |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, X., Qiao, L., Yang, B. et al. Investigation on users’ resistance intention to facial recognition payment: a perspective of privacy. Electron Commer Res 24, 275–301 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-022-09588-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-022-09588-y