Abstract

In this paper we show that the convex envelope over polytopes for a class of bivariate functions, including the bilinear and fractional functions as special cases, is characterized by a polyhedral subdivision of the polytopes, and is such that over each member of the subdivision the convex envelope has a given (although possibly only implicitly defined) functional form. For the bilinear and fractional case we show that there are three possible functional forms, which can be explicitly defined.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Al-Khayyal, F.A., Falk, J.E.: Jointly constrained biconvex programming. Math. Oper. Res. 8, 273–286 (1983)

Anstreicher, K.M., Burer, S.: Computable representations for convex hulls of low-dimensional quadratic forms. Math. Program. B 124, 33–43 (2010)

Anstreicher, K.M.: On convex relaxations for quadratically constrained quadratic programming. Math. Program. 136, 233–251 (2012)

Benson, H.P.: On the construction of convex and concave envelope formulas for bilinear and fractional functions on quadrilaterals. Comput. Opt. Appl. 27, 5–22 (2004)

Crama, Y.: Recognition problems for polynomials in 0–1 variables. Math. Program. 44, 139–155 (1989)

Kuno, T.: A branch-and-bound algorithm for maximizing the sum of several linear ratios. J. Global Optim. 22, 155–174 (2002)

Jach, M., Michaels, D., Weismantel, R.: The convex envelope of (\(n\)-1)-convex functions. SIAM J. Optim. 19(3), 1451–1466 (2008)

Laraki, R., Lasserre, J.B.: Computing uniform convex approximations for convex envelopes and convex hulls. J. Convex Anal. 15, 635–654 (2008)

Linderoth, J.: A simplicial branch-and-bound algorithm for solving quadratically constrained quadratic programs. Math. Program. 103, 251–282 (2005)

Locatelli, M., Schoen, F.: On convex envelopes for bivariate functions over polytopes. Math. Program. 144, 65–91 (2014)

Locatelli, M.: Alternative branching rules for some nonconvex problems. Opt. Methods Softw. 30, 365–378 (2015)

Locatelli, M.: A technique to derive the analytical form of convex envelopes for some bivariate functions. J. Global Optim. 59, 477–501 (2014)

Locatelli, M.: Convex Envelopes of Bivariate Functions Through the Solution of KKT Systems. Available in Optimization-Online at http://www.optimization-online.org/DB_HTML/2016/01/5280.html

McCormick, G.P.: Computability of global solutions to factorable nonconvex programs—Part I—Convex underestimating problems. Math. Program. 10, 147–175 (1976)

Meyer, C.A., Floudas, C.A.: Convex envelopes for edge-concave functions. Math. Program. 103, 207–224 (2005)

Mitchell, J.E., Pang, J.-S., Yu, B.: Convex quadratic relaxations of nonconvex quadratically constrained quadratic programs. Opt. Methods Softw. 29, 120–136 (2014)

Rikun, A.: A convex envelope formula for multilinear functions. J. Global Optim. 10, 425–437 (1997)

Sherali, H.D., Alameddine, A.: An explicit characterization of the convex envelope of a bivariate bilinear function over special polytopes. Ann. Oper. Res. 27, 197–210 (1992)

Tawarmalani, M., Sahinidis, N.V.: Semidefinite relaxations of fractional programs via novel convexification techniques. J. Global Optim. 20, 137–158 (2001)

Tardella, F.: On the existence of polyhedral convex envelopes. In: Floudas, C.A., Pardalos, P.M. (eds.) Frontiers in Global Optimization, pp. 563–574. Kluwer, Dordrecht (2003)

Tardella, F.: Existence and sum decomposition of vertex polyhedral convex envelopes. Opt. Lett. 2, 363–375 (2008)

Tawarmalani, M., Richard, J.-P.P., Xiong, C.: Explicit convex and concave envelopes through polyhedral subdivisions. Math. Program. 138, 531–577 (2013)

Zamora, J.M., Grossmann, I.E.: A Branch and Contract algorithm for problems with concave univariate, bilinear and linear fractional terms. J. Global Optim. 14, 217–249 (1999)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: On the solution of some systems

Appendix: On the solution of some systems

We need to show that the set of solutions of systems

with i, j, p distinct indexes in \(E'(P)\cup V'(P)\), has always finite cardinality. We prove two observations. The first one covers the case where at least two of the functions \(\eta _i,\eta _j,\eta _p\) in (63) are linear ones.

Observation 9.1

Assume that

for two distinct vertices \(v_i, v_j\) of P, while

-

either

$$\begin{aligned} \eta _p(a,b)=f(x_{v_p},y_{v_p})-a x_{v_p} - b y_{v_p}, \end{aligned}$$for some vertex \(v_p\ne v_i, v_j\);

-

or \(p\in E'(P)\) and \((a,b)\in D_p\) so that \(\eta _p\) is nonlinear.

Then, system (63) has a finite number of solutions.

Proof

If \(\eta _p\) is a linear function, the system is a linear one which can be written as follows

Since \(v_i, v_j, v_p\) are distinct vertices and, thus, are not aligned, this system has a unique solution.

If \(\eta _p\) is nonlinear, the system is

After eliminating variable a through the linear equation, i.e.,

the second equation can be rewritten as

(note that in case \(x_{v_i}=x_{v_j}\) we eliminate variable b rather than variable a). Recalling (19), we have

and recalling that \(t_p\) is a strictly concave function, the left-hand side of (64) is, with respect to b:

-

a strictly concave function if

$$\begin{aligned} m_p-\frac{y_{v_i}-y_{v_j}}{x_{v_i}-x_{v_j}}\ne 0; \end{aligned}$$ -

a linear function if

$$\begin{aligned} m_p-\frac{y_{v_i}-y_{v_j}}{x_{v_i}-x_{v_j}}=0. \end{aligned}$$

In both cases the number of roots of Equation (64) and, thus, the number of solutions of the system, is at most two. \(\square \)

The second observation covers the case where at least two of the functions \(\eta _i,\eta _j,\eta _p\) in (63) are nonlinear ones.

Observation 9.2

The system (63) with \(\eta _i, \eta _j\) nonlinear (i.e., \(i,j\in E'(P)\) and \((a,b)\in D_i\cap D_j\)) has a finite number of solutions: (i) in the region \(D_i\cap D_j\), if \(\eta _p\) is linear; (ii) in the region \(D_i\cap D_j\cap D_p\), if \(\eta _p\) is nonlinear (i.e., \(p\in E'(P)\)).

The proof of this result is more complicated with respect to the previous one and needs different intermediate results. We will only discuss the case where \(\eta _p\) is nonlinear (the proof for the case where \(\eta _p\) is linear is analogous).

Lemma 9.1

The Jacobian of system (63), with \(\eta _i, \eta _j\) nonlinear, is nonsingular over \(int(D_i\cap D_j)\).

Proof

Recalling (16), the Jacobian of this nonlinear system is equal to

where \(x_p(a,b)\) is defined in (10). Now, let us consider the three points

where we omit the dependency of \(s_i,s_j\) and \(x_p\) from a and b. Then, we can rewrite the Jacobian as

and notice that the Jacobian is nonsingular over the interior of \(D_h\cap D_w\). Indeed, it could be singular only if the three points are aligned, but this can never happen since the points \((x_i,y_i)\) and \((x_j,y_j)\) lie in the interior of distinct edges. \(\square \)

Next, we observe that the number of solutions lying over the border of \(D_i\cap D_j\) is finite. First we notice that, after the change of variables (48) (here we assume that i, j correspond to edges which are not parallel, but a similar development can also be done in the parallel case), the system (63) can be rewritten as follows

where \(\varphi _i,\varphi _j\) are defined in (51), while

and

With respect to the new variables \(z_i, z_j\), the region \(D_i\cap D_j\) becomes equal to the box \(I_i\cap I_j\), where \(I_i, I_j\) are defined in (50). By (53) we are able to eliminate, e.g., the variable \(z_j\),

Now we are able to prove the following result.

Lemma 9.2

The number of solutions of each system (63) (or of the equivalent system (66)) along the border of \(D_i\cap D_j\) is finite.

Proof

If we consider the equivalent system (66), we have that the border of \(D_i\cap D_j\) is in one-to-one correspondence with the border of \(I_i\cap I_j\). In a point along the border of \(I_i\cap I_j\) one variable, say \(z_i\), is fixed at its lower or upper bound. Then, the value of the other variable is uniquely defined by the solution of the equation

\(\square \)

Now, let us represent the system (63) in the general form

and prove the following lemma.

Lemma 9.3

If the determinant of the Jacobian of the system (63) is bounded away from 0 over \(D_i\cap D_j\), then the system has a finite number of solutions over \(D_i\cap D_j\).

Proof

By the mean value theorem we have that for some \(\lambda _1,\lambda _2\in [0,1]\), some solution \((a_0,b_0)\in D_i\cap D_j\) of the system (67), some direction \(u=(u_1,u_2)\), \(\Vert u\Vert =1\), and some \(\rho >0\),

Let

If the determinant of the Jacobian of the system is bounded away from 0 over \(D_i\cap D_j\), in view of the boundedness of the gradients \(\nabla \theta _1,\ \nabla \theta _2\) over \(D_i\cap D_j\), we can conclude, by continuity, that for any direction u and any sufficiently small \(\rho \) value, that the matrix \(\Gamma (a_0,b_0,\rho ,u)\) is nonsingular. Therefore, all points whose distance from \((a_0,b_0)\) is lower than \(\rho \) can not be solutions of the system since

for all \(u\ne 0\), i.e., there is a circle with radius \(\rho \) around the solution of the system \((a_0,b_0)\) such that there is no other solution of the system within the circle. But this implies that there can not be an infinite number of solutions. \(\square \)

This proves Observation 9.2 when the determinant of the Jacobian of the system is bounded away from 0 over \(D_i\cap D_j\). In case the determinant of the Jacobian vanishes at the border of \(D_i\cap D_j\), then it might happen (though unlikely) that there exists an infinite sequence of solutions in the interior of \(D_i\cap D_j\) which converges to a solution lying at the border of \(D_i\cap D_j\) (recall that, in view of Lemma 9.2, the number of solutions lying at the border of \(D_i\cap D_j\) is certainly finite). In fact, this situation can not happen since such solutions at the border (if any) are certainly isolated. This will be proved in the next two lemmas. Before stating and proving such lemmas, we notice that it is relatively simple to detect the points along the border of \(D_i\cap D_j\) at which the determinant of the Jacobian vanishes. The first case where this happens is when i and j correspond to adjacent edges. In this case the equality \(\eta _i(a,b)=\eta _j(a,b)\) is satisfied along the border of \(D_i\cap D_j\) only when \(s_i(a,b)=s_j(a,b)\) is the x-coordinate of the common vertex \(\bar{v}\) of the two edges (so that also the determinant of the Jacobian vanishes). If i and j do not correspond to adjacent edges, then the second case where the determinant of the Jacobian vanishes is when: (i) p corresponds to an edge which is adjacent to both the edges corresponding to i and j; (ii) \((s_i(a,b),m_i s_i(a,b)+q_i)\) and \((s_j(a,b),m_j s_j(a,b)+q_j)\) are, respectively, the common vertex \(\bar{v}_1\) between edge i and edge p, and the common vertex \(\bar{v}_2\) between edge j and edge p. However, this case can be reduced to the previous one. Indeed, any solution \((a^*,b^*)\) of the system (63) for this case is such that

where \(x_p(a^*,b^*), y_p(a^*,b^*)\) are defined in (10) and are the coordinates of a point along the edge corresponding to p. Let us denote by \(\sigma =(\sigma _x,\sigma _y)\) such point (we omit the dependency of \(\sigma \) on \(a^*,b^*\)). If \(\sigma \ne \bar{v}_1,\bar{v}_2\), then we must have that

Since

(recall that \(\bar{v}_1,\bar{v}_2, \sigma \) all lie along the edge with index p), and since f is strictly convex along the edge with index p, then (69) can not hold and, thus, we might have a solution of the system only if \( \sigma =\bar{v}_1\ \text {or}\ \bar{v}_2\), i.e., \(s_p(a^*,b^*)=s_i(a^*,b^*)\) (or \(s_p(a^*,b^*)=s_j(a^*,b^*)\)), where p and i (or j) are adjacent edges as in the previous case.

Now we first prove that, when \(\eta _p\) is linear, i.e.,

for some vertex \(v_r\) of P (not belonging to edges with indexes i, j), any solution of system (63) lying at the border of \(D_i\cap D_j\) is isolated.

Lemma 9.4

If:

-

\(\eta _p(a,b)\) is given by (70), where \(v_r\) is not a vertex of the edges with indexes i, j;

-

the edges with indexes i, j are adjacent;

-

there exists a solution of the system (63) at the border of \(D_i\cap D_j\) where the determinant of the Jacobian vanishes;

then the solution of the system is isolated.

Proof

We assume, without loss of generality, that \(m_i>m_j\). Moreover, we only discuss the case where

(the other cases can be treated in a similar way). As previously observed, the determinant of the Jacobian vanishes only if i and j correspond to adjacent edges and we have \(s_i(a,b)=s_j(a,b)=x_{\bar{v}}\), where \(\bar{v}\) is the common vertex of the two edges. The equality

can be written as follows, after substituting a and b with \(z_i\) and \(z_j\) through (48) and recalling (19)

The equality \(\eta _i(a,b)=\eta _j(a,b)\) can be written as

where \(\varphi _i, \varphi _j\) are defined in (51). From this equality we notice that if \(z_i\) is at the extreme of \(I_i\) for which we have \(s_i(a,b)=s_j(a,b)=x_{\bar{v}}\) and we move it towards the interior of \(I_i\), then: (i) either \(z_j\), as a function of \(z_i\), moves outside \(I_j\); (ii) or \(z_j\) also moves towards the interior of \(I_j\). In the case (i) the border solution of the system is obviously isolated in \(I_i\cap I_j\) since as we move from it we also move outside \(I_i\cap I_j\). In the case (ii) we proceed as follows. In view of (73), we can use the implicit function theorem to compute the derivative of \(z_j\) with respect to \(z_i\) in the interior of \(I_i\)

Then, after a few computations, the derivative with respect to \(z_i\) of the left-hand side of (72) is equal to

Recalling that \(t'_i(z_i)=-(f'_{i})^{-1}(z_i)=-s_i\) and \(t'_j(z_j)=-(f'_{j})^{-1}(z_j)=-s_j\) (see (7) and (18)), this can also be written as

where \(\Delta _{ji}()\) is defined in (62) (note that we are omitting the dependency of \(s_i\) and \(s_j\) from a, b). In view of (71), we have that

Moreover, in the interior of \(I_i\cap I_j\) we have

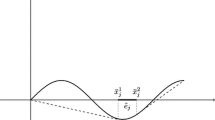

and as we approach the border, i.e., as \(s_i, s_j\rightarrow x_{\bar{v}}\), we have that both quantities converge to 0 (see also Fig. 5). Then, there exists a neighborhood of the extreme of \(I_i\) at which we have \(s_i=s_j=x_{\bar{v}}\), where

The case where \(z_i\) is in the interior of \(I_i\) and \(z_j\) in the interior of \(I_j\) under the assumptions (71)

so that over this neighborhood the left-hand side of (72) is strictly increasing. Thus, we can conclude that if we have a root of (72) at the extreme of \(I_i\) where \(s_i=s_j=x_{\bar{v}}\), i.e., if we have a solution of the system (63) lying at the border of \(D_i\cap D_j\) and at which the determinant of the Jacobian vanishes, then this solution is isolated. \(\square \)

When \(\eta _p\) is nonlinear, the proof of the same result for system (63) is a bit more complicated but is based on the same ideas.

Lemma 9.5

When \(\eta _p\) is nonlinear (i.e., \(p\in E'(P)\) and \((a,b)\in D_p\)), and i, j are the indexes of adjacent edges, if there exists a solution of the system (63) within \(D_i\cap D_j\cap D_p\) where the determinant of the Jacobian vanishes, then this solution is isolated.

Proof

We assume again, without loss of generality, that \(m_i>m_j\), and we only discuss the case where (71) is satisfied (the other cases can be treated in a similar way). As previously observed, the determinant of the Jacobian vanishes only if i and j are adjacent edges and \(s_i(a,b)=s_j(a,b)=x_{\bar{v}}\), where \(\bar{v}\) is the common vertex of the two edges. The equality

can also be written as follows, after the change of variables (48)

where

The derivative of \(z_j\) with respect to \(z_i\) in the interior of \(I_i\) is given by (74). Then, after a few computations, the derivative with respect to \(z_i\) of the left-hand side of (75) is equal to

(recall that \(\Delta _{ji}()\) is defined in (62)). As before, if \(z_i\) is at the extreme of \(I_i\) for which we have \(s_i=s_j=x_{\bar{v}}\) and we move it towards the interior of \(I_i\), then: (i) either \(z_j\), as a function of \(z_i\), moves outside \(I_j\); (ii) or \(z_j\) also moves towards the interior of \(I_j\). Similarly, as we move \(z_i\) towards the interior of \(I_i\) we have that: (iii) either \(z_p\), as a function of \(z_i\), moves outside \(I_p\) (in case \(z_p\) lies along the border of \(I_p\)); (iv) or \(z_p\) also moves towards the interior of \(I_p\) (if \(z_p\) is at the border of \(I_p\)), or remains in the interior of \(I_p\). Once again, if either (i) or (iii) is true, then the border solution of the system is obviously isolated in \(I_i\cap I_j\cap I_p\) since as we move from it we also move outside \(I_i\cap I_j\cap I_p\). Instead, if (ii) and (iv) are true, we proceed as follows. In the interior of \(I_i\cap I_j\) we have

while in \(I_p\) we have that

(see also Fig. 6). As we approach the border, i.e., as \(s_i, s_j\rightarrow x_{\bar{v}}\), we have that \(\Delta _{ji}(s_i),\Delta _{ji}(s_j)\) both converge to 0, while for some \(\delta >0\)

(see again Fig. 6). Then, there exists a neighborhood of the extreme of \(I_i\) at which \(s_i=s_j=x_{\bar{v}}\), where (76) is strictly positive so that, over this neighborhood the left-hand side of (75) is strictly increasing. Thus, if (75) holds at the extreme of \(I_i\) where \(s_i=s_j=x_{\bar{v}}\), i.e., if we have a solution of the system (63) lying at the border of \(D_i\cap D_j\) and at which the determinant of the Jacobian vanishes, then this solution is isolated. \(\square \)

Now, the proof of Observation 9.2 is a consequence of Lemmas 9.1–9.5.

The case where \(z_i\) is in the interior of \(I_i\), \(z_j\) in the interior of \(I_j\), and \(z_p\in I_p\) under the assumptions (71)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Locatelli, M. Polyhedral subdivisions and functional forms for the convex envelopes of bilinear, fractional and other bivariate functions over general polytopes. J Glob Optim 66, 629–668 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10898-016-0418-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10898-016-0418-4