Abstract

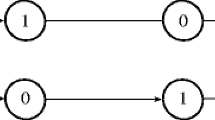

It is argued that, given certain reasonable premises, an infinite number of qualitatively identical but numerically distinct minds exist per functioning brain. The three main premises are (1) mental properties supervene on brain properties; (2) the universe is composed of particles with nonzero extension; and (3) each particle is composed of continuum many point-sized bits of particle-stuff, and these points of particlestuff persist through time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Notes

We are agnostic about the question of whether numerically distinct minds can supervene on non-disjoint but non-identical mereological sums of points of particle-stuff. If one had a solution to Peter Unger’s (1980) Problem of the Many, then one would be more likely to have an answer to this question. It’s perhaps worth mentioning, though, that the Problem of the Many Minds is not the Problem of the Many applied to minds—the Problem of the Many Minds focuses on disjoint mereological sums, while the Problem of the Many applies only to non-disjoint mereological sums.

This objection is owed to an anonymous referee of Minds and Machines.

We owe this suggestion, along with the reference to the results of Putnam (1988), to an anonymous referee of Minds and Machines.

Here it may be worth noting what we do not intend by “a point of particle-stuff”: we do not intend a point-sized portion of stuff that is not itself a material object but which together with some other stuff constitutes an indivisible material object. Such a reading reflects recent work on a dual ontology of stuff and things where the constitution relation is a relation between some stuff and a thing; we do not intend to be read in this way.

References

Putnam, H. (1988). Representation and reality. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lewis, D. (1986). ‘Causation’ and postscripts. In Philosophical papers Volume II (pp. 159–213). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Unger, P. (1980). The problem of the many. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 5, 411–467.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Thanks to the audience at an informal talk given at Princeton University, which included Allison Dawe, Cian Dorr, Benj Hellie, Brian Kierland, Aaron Konopasky, and Chad Mohler. For helpful comments on a previous version of this paper, we thank David Lewis. And thanks to an anonymous referee of Minds and Machines.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Monton, B., Goldberg, S. The problem of the many minds. Minds & Machines 16, 463–470 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-006-9045-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-006-9045-z