Abstract

Many who advocate dynamical systems approaches to cognitive science believe themselves committed to the thesis of extended cognition and to the rejection of representation. I argue that this belief is false. In part, this misapprehension rests on a warrantless re-conception of cognition as intelligent behavior. In part also, it rests on thinking that conceptual issues can be resolved empirically. Once these issues are sorted out, the way is cleared for a dynamical systems approach to cognition that is free to retain the standard conception of cognition as taking place in the head, and over representations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Notes

Van Gelder and Port (1995) trace its application to psychology back to the 1940s, especially in the field of cybernetics. However, as they recognize, it was not until the late 1980s, when dynamical systems theory was deployed for the analysis of some connectionist networks, that DCS began to pick up speed.

Of course, this marks a sort of idealization given that predators and prey come in discrete packages.

A referee kindly reminded me that this conception of cognition of course predates cognitive science, having roots in Descartes as well as the British Empiricists.

This would be an example of what Clark and Toribio (1994) describe as a representation hungry process.

I’m assuming that when dynamicists appeal to an organism’s constant contact with the environment, they also see the contact as being with some stimulus that specifies the relevant features of the environment. If constant contact were with a stimulus that did not specify its source, then it is hard to know what use constant contact with it would afford.

References

Adams, F., & Aizawa, K. (2008). The bounds of cognition. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Bechtel, W. (1998). Representations and cognitive explanations: Assessing the dynamicist’s challenge in cognitive science. Cognitive Science, 22, 295–318.

Beer, R. (2000). Dynamical approaches to cognitive science. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4, 91–99.

Beer, R. (2003). The dynamics of active categorical perception in an evolved model agent. Adaptive Behavior, 11, 209–243.

Brooks, R. (1991). Intelligence without representation. Artificial Intelligence, 47, 139–159.

Buss, D. (Ed.). (2005). The handbook of evolutionary psychology. Hoboken: Wiley.

Chemero, A. (2009). Radical embodied cognitive science. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chemero, A., & Silberstein, M. (2007). After the philosophy of mind: Replacing scholasticism with science. Philosophy of Science, 75, 1–27.

Chemero, A., & Silberstein, M. (2008). Defending extended cognition. In V. Sloutsky, B. Love, & K. McRae (Eds.), Proceedings of the 30th annual conference of the cognitive science society (pp. 129–134). New York: Psychology Press.

Clark, A. (2007). Re-inventing ourselves: The plasticity of embodiment, sensing, and mind. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 32, 263–282.

Clark, A. (2008). Supersizing the mind: Embodiment, action, and cognitive extension. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis, 58, 7–19.

Clark, A., & Toribio, J. (1994). Doing without representing? Synthese, 101, 401–431.

Dretske, F. (1988). Explaining behavior: Reasons in a world of causes. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Egan, F. (1991). Must psychology be individualistic? The Philosophical Review, 100, 179–203.

Fink, P., Foo, P., & Warren, W. (2009). Catching fly balls in virtual reality: A critical test of the outfielder problem. Journal of Vision, 9, 1–8.

Fodor, J. (1975). The language of thought. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Fodor, J. (1990). A theory of content and other essays. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin.

Haken, H., Kelso, S., & Bunz, H. (1985). A theoretical model of phase transitions in human hand movements. Biological Cybernetics, 51, 347–442.

Hatfield, G. (1988). Representation and content in some (actual) theories of perception. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 19, 175–214 [as reprinted in Hatfield (2009, pp. 50–87)].

Hatfield, G. (1991). Representation in perception and cognition: Connectionist affordances. In W. Ramsey, S. Stich, & D. Rumelhart (Eds.), Philosophy and connectionist theory (pp. 163–195). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hatfield, G. (2009). Perception and cognition: Essays in the philosophy of psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kelso, S. (1995). Dynamic patterns: The self-organization of brain and behavior. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lachman, R., Lachman, J., & Butterfield, E. (1979). Cognitive psychology and information processing: An introduction. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Marr, D. (1982). Vision. San Francisco: Freeman.

McBeath, M., Shaffer, D., & Kaiser, M. (1995). How baseball outfielders determine where to run to catch fly balls. Science, 268, 569–573.

Rumelhart, D., Smolensky, P., McClelland, J., & Hinton, G. (1986). Schemata and sequential thought processes in PDP models. In D. Rumelhart & J. McClelland (Eds.), Parallel distributed processing: Explorations in the microstructure of cognition, vol. 2, psychological and biological models (pp. 7–57). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Schneider, W. (1987). Connectionism: Is it a paradigm shift for psychology? Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 19, 73–83.

Segal, G. (1989). Seeing what is not there. The Philosophical Review, 98, 189–214.

Shaffer, D., & McBeath, M. (2005). Naïve beliefs in baseball: Systematic distortion in perceived time of apex for fly balls. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 31, 1492–1501.

Shapiro, L. (2011). Embodied cognition. New York: Routledge.

Spencer, J., & Schöner, G. (2003). Bridging the representational gap in the dynamical systems approach to development. Developmental Science, 6, 392–412.

Spivey, M. (2007). The continuity of mind. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stephen, D., & Dixon, J. (2009). The self-organization of insight: Entropy and power laws in problem solving. The Journal of Problem Solving, 2, 72–101.

Stich, S. (1983). From folk psychology to cognitive science. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Thelen, E., Schöner, G., Scheier, C., & Smith, L. (2001). The dynamics of embodiment: A field theory of infant perseverative reaching. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24, 1–86.

van Gelder, T., & Port, E. (1995). It’s about time: An overview of the dynamical approach to cognition. In R. Port & T. van Gelder (Eds.), Mind as motion: Explorations in the dynamics of cognition (pp. 1–44). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ward, R., & Ward, R. (2009). Representation in dynamical agents. Neural Networks, 22, 258–266.

Wilson, R. (1994). Wide computationalism. Mind, 103, 351–372.

Wilson, R. (2004). Boundaries of the mind. The individual in the fragile sciences: Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

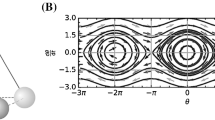

I'm grateful to audiences at the University of Delaware and the University of Pennsylvania for constructive discussion. Ken Aizawa deserves special thanks for his detailed comments and assistance with several of the figures within.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shapiro, L.A. Dynamics and Cognition. Minds & Machines 23, 353–375 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-012-9290-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-012-9290-2