Abstract

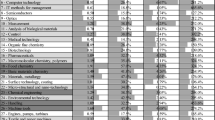

This article focuses on the cross-country distribution of mining patent families during the period of 1970 − 2018. Alternatives measures of concentration indicate that only a few countries account for most mining inventions (e.g., China, Germany, Japan, the United States), and that the composition of such countries has remained relatively stable over time. This is also true for patent families of all technology fields. On the other hand, the evidence shows that those countries relatively specialized in mining technologies do not necessarily have a high share of mining inventions (e.g., Peru and Indonesia). These stylized facts are complemented with panel-regression models of the number of mining patent families—distinguishing between patented inventions and utility models—-, of mining patent-family ranks, and of relative specialization in mining. The empirical findings show that important drivers of mining patent families are mineral prices and production, family features, and the number of patent families of all technology fields (i.e., overall inventive performance). Moreover, the evidence shows that increments in mineral rents/GDP have a positive impact on the likelihood of relative specialization in some mining technologies, such as Blasting, Mining, and Processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The World Bank defines mineral rents are the difference between the value of production for a stock of minerals at world prices and their total costs of production. Minerals included in the calculation are tin, gold, lead, zinc, iron, copper, nickel, silver, bauxite, and phosphate.

In related literature, Bickenbach, Bode, and Krieger‐Boden (2013) show that the difference between absolute and relative Theil localization indices of economic activity depends only on how strongly the patterns of industrial specialization and of regional concentration of the aggregate economy differ from the corresponding references.

The original WIPO mining database included about 45,000 records that did not have any information on country of origin and assignee type (business, research center, educational institution, or individual). These were deleted. In addition, many records had missing information on country of origin, which was entered manually when possible. This task was relatively simple for educational institutions and businesses (typically, headquarter location was considered). Missing information on individuals was kept this way to avoid possible errors.

Computations and graphs are obtained using the Stata lorenz routine developed by Jann op cit.

Patent rights are essentially territorial, that is, they apply only in the jurisdiction of the patent office that grants the right.

A single filing of a PCT application is made with a Receiving Office (RO) in one language. It then results in a search performed by an International Searching Authority (ISA), accompanied by a written opinion about the patentability of the invention. Ultimately, the grating of patents remains under the control of national and regional offices due to the territorial nature of patent protection.

We rule out any collinearity issues among the explanatory variables due to the approximately linear association between the mining and all-technology ranks (Fig. 3). Indeed, the mean variance inflation factor (VIF) for the mining and all-technology ranks and lagged mineral rents/GDP is 3.85, whereas none of the individual VIFs exceed 6. In practice, VIFs greater than 10 are considered problematic (e.g., Greene 2018, pages 94–95). Similarly, the mean VIF for the mining and all-technology ranks and lagged log mineral production is 3.95. Once again, the individual VIFs do not exceed 6.

The RSI for each mining technology is computed as \({\text{log}}_{10} \left( {\frac{{{\raise0.7ex\hbox{${{\text{P}}_{{\text{C}}}^{{{\text{MT}}_{{\text{i}}} }} }$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{P}}_{{\text{C}}}^{{{\text{MT}}_{{\text{i}}} }} } {{\text{P}}_{{\text{C}}}^{{\text{M}}} }}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${{\text{P}}_{{\text{C}}}^{{\text{M}}} }$}}}}{{{\raise0.7ex\hbox{${{\text{P}}_{{\text{W}}}^{{{\text{MT}}_{{\text{i}}} }} }$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{P}}_{{\text{W}}}^{{{\text{MT}}_{{\text{i}}} }} } {{\text{P}}_{{\text{W}}}^{{\text{M}}} }}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${{\text{P}}_{{\text{W}}}^{{\text{M}}} }$}}}}} \right)\) where \({\text{P}}_{{\text{C}}}^{{{\text{MT}}_{{\text{i}}} }}\) and \({\text{P}}_{{\text{W}}}^{{{\text{MT}}_{{\text{i}}} }}\) represent the number of patent families in mining technology (MT) ‘i’ filed by country C and across the world, respectively, whereas \({\text{P}}_{\text{C}}^{\text{M}}\) and \({\text{P}}_{\text{W}}^{\text{M}}\) are the mining patent families filed by country C and across the world, respectively.

References

Aksnes, D., van Leeuwen, T., & Sivertsen, G. (2014). The effect of booming countries on changes in the relative specialization index (RSI) on country level. Scientometrics, 101, 1391–1401.

Barron, O., Byard, D., Kile, C., & Riedl, E. (2002). High-technology intangibles and analysts’ forecasts. Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 289–312.

Bickenbach, F., Bode, E., & Krieger-Boden, C. (2013). Closing the gap between absolute and relative measures of localization, concentration or specialization. Papers in Regional Science, 92(3), 465–479.

Bravo-Ortega, C., and J. J Price Elton (2019). “Innovation and IP rights in the Chilean copper mining sector: the role of the mining, equipment, technology and services firms.” World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Economic Research Working Paper No. 54, wipo.int/publications/en/details.jsp?id=4418

Breschi, S. (2000). The geography of innovation: A cross-sector analysis. Regional Studies, 34(3), 213–229.

Calzada-Olvera, B., and M. Iizuka (2020). “How does innovation take place in the mining industry? Understanding the logic behind innovation in a changing context.” UNU-MERIT Working Paper #2020–019. https://www.merit.unu.edu/publications/working-papers/abstract/?id=8511

Chain, C. P., Santos, A., Castro, L., & Prado, J. (2019). Bibliometric analysis of the quantitative methods applied to the measurement of industrial clusters. Journal of Economic Surveys, 33(1), 60–84.

Conover, W. J. (2012). The rank transformation—an easy and intuitive way to connect many nonparametric methods to their parametric counterparts for seamless teaching introductory statistics courses. Wires Computational Statistics, 4, 432–438.

Crespi, G., Katz, J., & Olivari, J. (2018). Innovation, natural resource-based activities and growth in emerging economies: the formation and role of knowledge intensive service firms. Innovation and Development, 8(1), 79–101.

Daly, A., Valacchi, G., and Raffo, J., (2019). “Mining patent data: Measuring innovation in the mining industry with patents.” World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Economic Research Working Paper No. 56, wipo.int/publications/en/details.jsp?id=4420

Ellison, G., Glaeser, E., & Kerr, W. (2010). What causes industry agglomeration? Evidence from co-agglomeration patterns. The American Economic Review, 100(3), 1195–1213.

Feldman, M., & Florida, R. (1994). The geographic sources of innovation: Technological infrastructure and product innovation in the United States. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 84(2), 210–229.

Fernandez, V. (2020). Innovation in the global mining sector and the case of Chile. Resources Policy., 68, 101690.

Forman, C., and Goldfarb A., (2020). “Concentration and agglomeration of IT innovation and entrepreneurship: Evidence from patenting.” NBER Working Paper 27338

Fornahl, D., & Brenner, T. (2009). Geographic concentration of innovative activities in Germany. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 20, 163–182.

Frederiksen, T. (2019). Political settlements, the mining industry, and corporate social responsability in developing countries. The Extractive Industries and Society, 6, 162–170.

Greene, W. (2018). Econometric Analysis. Eighth edition. Pearson Education. 1176 p. ISBN-13: 978-0134461366.

Gurmu, S., & Pérez-Sebastián, F. (2008). Patents, R&D and lag effects: evidence from flexible methods for count panel data on manufacturing firms. Empirical Economics, 35(3), 507–526.

Hall, B. (2020). “Patents, innovation, and development.” NBER Working Paper 27203.

Harhoff, D., Scherer, F., & Vopel, K. (2003). Citations, family size, opposition and the value of patent rights. Research Policy, 32(8), 1343–1363.

Hines, W., Montgomery, D., Goldsman, D., & Borror, C. (2003). Probability and statistics in engineering (4th ed.). . Hoboken: Wiley.

Jaffe, A., Trajtenberg, M., & Henderson, R. (1996). Geographic localization of knowledge spillovers as evidence of patent citations. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 63, 577–598.

Jann, B. (2016). Estimating Lorenz and concentration curves. The Stata Journal, 16(4), 837–866.

Mbilima, F. (2019). “Extractive industries and local sustainable development in Zambia: The case of corporate social responsibility of selected metal mines.” Resources Policy, 101441, in press, corrected proof.

Naldi, M. and M. Flamini (2014). “The CR4 Index and the interval estimation of the herfindahl-hirschman index: an empirical comparison.” https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01008144/document

Sanchez, F., & Hartlieb, P. (2020). Innovation in the mining industry: Technological trends and a case study of the challenges of disruptive innovation. Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42461-020-00262-1

Sterlacchini, A. (2020). Trends and determinants of energy innovations: Patents, environmental policies and oil prices. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 23(1), 49–66.

Valacchi, G., J. Raffo, A. Daly, and D. Humphreys (2019). “Innovation in the mining sector and cycles in commodity prices.” World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Economic Research Working Paper No. 55, wipo.int/publications/en/details.jsp?id=4419

Wen, M. (2004). Relocation and agglomeration of Chinese industry. Journal Development Economics, 73, 329–347.

WIPO (2019). World intellectual property indicators 2019. Geneva: World Intellectual Property Organization, wipo.int/publications/en/details.jsp?id=4464

Wunsch-Vincent, S., Kashcheeva, M., & Zhou, H. (2015). International patenting by Chinese residents: Constructing a database of Chinese foreign-oriented patent families. China Economic Review, 36, 198–219.

Funding

Funds provided by Programa de Apoyo a la Investigación (PAI)-UAI, Grant DII_IND_2020_06, are greatly acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Robustness check: time sub-periods. See Tables

12,

13 and

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fernandez, V. Cross-country concentration and specialization of mining inventions. Scientometrics 126, 6715–6759 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04044-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04044-4